Even streets that are regarded as urban and walkable still allocate the lion's share of space for the exclusive use of cars, squeezing everything else to the margins.

By Ryan McGreal

Published January 20, 2016

The always-inspiring Strong Towns has just posted an excellent article on the bias of street design. Looking at a walkable urban street in Hoboken, New Jersey - one of the most walkable cities in the United States - the author writes:

How can we say that our design does not influence behaviour when clearly 68 percent of the street has been designed just for cars? This is what I call a 'biased' street, because it is biased towards a particular mode of transportation.

As the author notes, even streets that are regarded as urban and walkable still allocate the lion's share of space for the exclusive use of cars, squeezing everything else to the margins.

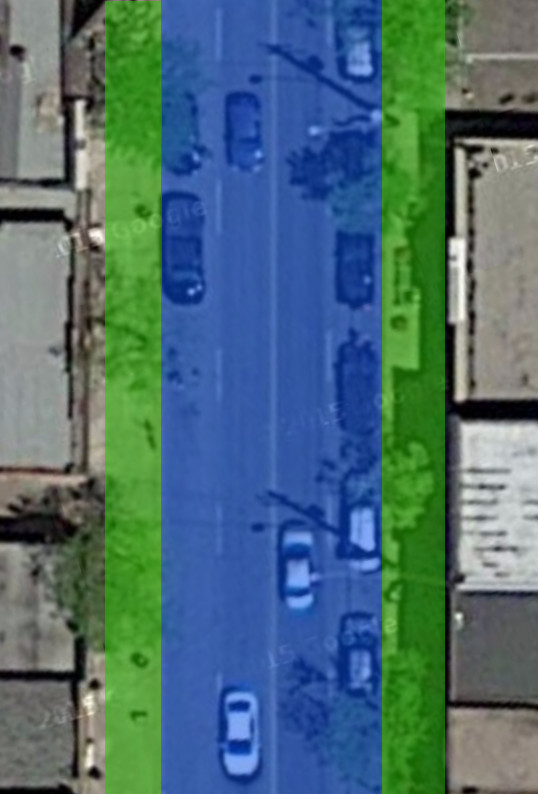

Curious as to how this might apply in Hamilton, I took a look at James Street North, one of the city's most famously walkable urban streets, to see how it apportions its scarce right-of-way.

James Street North, just north of Robert Street. Blue area is dedicated for cars, green area for everything else (Image Credit: Google Maps)

On the map above, I've added shading to delineate the distribution of use on the street. The blue area in the centre is for the exclusive use of cars. The green areas on the sides are for everything else: walking, chatting, shopping, sitting, socializing and all of the other activities that people undertake when they're enjoying (or trying to enjoy) public space.

On James North, a walkable urban commercial strip, fully 70 percent of the street right-of-way - the public space between the properties - is for the exclusive use of cars.

The remaining 30 percent - two skinny ribbons on either side of the car area - provides the space for all the other things that go on a street: sidewalks, outdoor seating and street furniture, street trees, patios, outdoor display cases, street art, lampposts and utility poles, signs, and so on.

Of course, looking at a satellite image is not a precise measurement of the street, but it certainly gets us clearly in the ballpark of the actual breakdown. Even if the actual split is several percent different, we're still left with a street in which most of the space is reserved for cars.

But maybe James North is an anomaly? I also checked Locke Street South, another famously walkable urban commercial centre in the lower city, just southwest of the downtown core.

Locke Street South, just north of Tuckett Street. Blue area is dedicated for cars, green area for everything else (Image Credit: Google Maps)

The distribution of space is nearly identical: 70 percent of Locke Street is for the exclusive use of cars and just 30 percent is for everything else.

How about Ottawa Street North, the burgeoning urban commercial street in the east end?

Ottawa Street North, just north of Cannon Street. Blue area is dedicated for cars, green area for everything else (Image Credit: Google Maps)

Once again, we see the lion's share of space going to the exclusive use of cars - around 67 percent, based on my back-of-the-envelope methodology - with the remaining 33 percent for everything else that people do on a city street.

Remember: these are the most walkable streets in Hamilton. They are hardly considered car-friendly, even though they are overwhelmingly dedicated to the exclusive use of cars!

The author of the Strong Towns article goes on to draw a sharp distinction between a street - the public space connecting buildings in a built-up environment - and a road - a public right-of-way designed to move people from someplace to someplace else.

This distinction is a common refrain on Strong Towns, the website that gave us the concept of the stroad: a street-road hybrid that combines dangerously fast through traffic with local use, with predictably disastrous results.

For at least the past half-century, most North American cities have almost exclusively designed their arterial streets as stroads. Such stroads are ubiquitous in postwar suburbs, and indeed they have tended to grow progressively wider, more indimidating and more dangerous for pedestrians with each subsequent iteration.

You can see this directly as you move farther from the city centre: arterials grow progressively more ugly, overbuilt and impassable to anything other than driving.

Hamilton has plenty of "stroads", including both newer suburban designs and older urban streets that have been deformed into multi-lane thoroughfares (often by converting them to one-way traffic).

Hamilton's stroads are disproportionately the stage on which pedestrians are struck and killed in vehicle collisions. In the past couple of years, pedestrians have been struck at, for just a few examples, Rymal Road and Upper Centennial, Stone Church Road and Rochelle Avenue, Queen Street at Main and at Herkimer, Mohawk Road and Penlake Court, Highway 8 and Green Road, Cootes Drive and York Street, York and Hess, Barton and Catharine, Queenston and Reid, and Mud Street and Winterberry Drive.

But as we have seen, even those urban, human-scaled streets that have survived the postwar commitment to traffic flow - or, in the case of James North and Locke Street - have been restored somewhat toward their original use after decades of abuse - still manage to set the bar distressingly low in terms of committing real public space for urban use.

By JasonL (registered) | Posted January 20, 2016 at 15:16:57

looks like the proof is in. The war on cars is real. Those green stripes are WAY too wide

By kevlahan (registered) | Posted January 20, 2016 at 17:01:01

Interestingly, when Haussman was re-designing Paris in the 19th century with the goal of improving attractiveness and mobility by replacing narrow medieval streets with broad avenues he specifically mandated that the right of way be equally divided between sidewalk and space for vehicles.

This means that even the wide busy avenues are still comfortable for pedestrians and have space for cafe terraces, trees, street furniture etc. It also improves conditions for people who live on the streets. This 50% rule seems like a simple design principle that yields good results.

How much space is given over to cares on streets like Main St at Hess? A rough calculation suggests about 80%!

https://www.google.ca/maps/place/179+Hess+St+N,+Hamilton,+ON+L8R+2T1/@43.2574054,-79.8782414,37m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m2!3m1!1s0x882c9b7ff0263fb7:0x7f4df929140ac58d!6m1!1e1

US cities often have much wider sidewalks downtown than Hamilton, and even a larger proportion of right of way dedicated to them. For example, Appleton Wisconsin has about 25% of its right of way to sidewalks and much wider sidewalks than Hamilton: 5m wide and even wider at intersections due to bump outs (even the sidewalks on James St N are only about 3.5m wide, and they are some of the widest downtown).

https://www.google.ca/maps/place/Appleton,+WI,+USA/@44.2617074,-88.4072592,100m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m2!3m1!1s0x8803b682b903f6c9:0x9ca1d6a50675935b!6m1!1e1

Comment edited by kevlahan on 2016-01-20 17:13:34

By mdrejhon (registered) - website | Posted January 20, 2016 at 17:49:15 in reply to Comment 116195

It would be interesting to analyze the 2011 LRT plans to determine what the allocations are, as in many sections of the LRT corridor are planned sidewalk widenings to 2.5 meters.

(Main near Ottawa Street)

Plans do change, though it is reported the majority of the B-Line plans will be reused with modifications.

Comment edited by mdrejhon on 2016-01-20 17:49:57

By KevinLove (registered) | Posted January 21, 2016 at 10:53:15

The author of the Strong Towns article goes on to draw a sharp distinction between a street - the public space connecting buildings in a built-up environment - and a road - a public right-of-way designed to move people from someplace to someplace else.

Kevin's comment:

This is a distinction made by law in The Netherlands, with streets being prevented from being through roads.

A quotation from:

http://www.swov.nl/rapport/R-2005-05.pdf

The key to arriving at a sustainably safe traffic system lies in the systematic and consistent application of three safety principles: − functionality − homogeneity − predictability

The functionality of the road system is important in that actual use matches with intended use, as designed by road authorities. This produces a road network with three categories: through-roads, distributor roads, and access roads (Figure 2.1). Each road or street may only have one function (e.g. a distributor road may not give direct access to houses, shops, or offices). The homogeneity of the road system is meant to avoid significant differences in speeds, driving directions, and mass (preferably by segregating incompatible traffic types, and if this is not possible or desirable, by forcing motorized traffic to drive slowly).

Comment edited by KevinLove on 2016-01-21 10:54:56

By z jones (registered) | Posted January 22, 2016 at 07:36:14 in reply to Comment 116206

"Get out of my way"

And the mask comes flying off.

By peon (anonymous) | Posted January 22, 2016 at 16:45:24 in reply to Comment 116207

Is it lonely up there on that pedestal?

By Danny boy (anonymous) | Posted January 27, 2016 at 11:44:44

Take an overhead view of a motor vehicle

Take note of the surface area requirements for a motor vehicle

Take an overhead view of a human

Take note of the surface area requirements for a human

Take an overhead view of a road

Apply to this observation the notes taken on the surface area requirements of a motor vehicle

Take an overhead view of a sidewalk

Apply to this observation the notes taken on the surface area requirements of a human

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?