Quarries in the Eramosa dolomite were the preferred local source of stone for major buildings in Hamilton in the 1870s and 1880s.

By Gerard V. Middleton

Published August 23, 2011

This is the second article in a series on Hamilton building stone. You can read part 1.

By the 1860s, the supply of Whirlpool ashlar from quarries at the base of the escarpment in Hamilton and Dundas was almost exhausted ( see Part 1). A good, toll-free access road up the Mountain was built in 1873 (Jolley Cut) and many quarries were then developed in the Eramosa dolomite. It became the preferred local stone for major buildings in Hamilton (1870s to 1880s).

Hamilton's "stone age" ended in the 1890s, when it became much cheaper to use mass produced bricks (and later, concrete). Even before then, local stone faced stiff competition from stones "imported" from Ohio (sandstone), Indiana (limestone), and Queenston (dolomitic limestone).

Rapid urban development took place on the Mountain in the 1950s Architectural Heritage: the population increased from 10,000 in 1945 to 100,000 in 1970. As a result, all the quarries have now been built over, and the only good outcrops of Eramosa dolomite are those than can be seen (briefly!) by driving along the Linc.

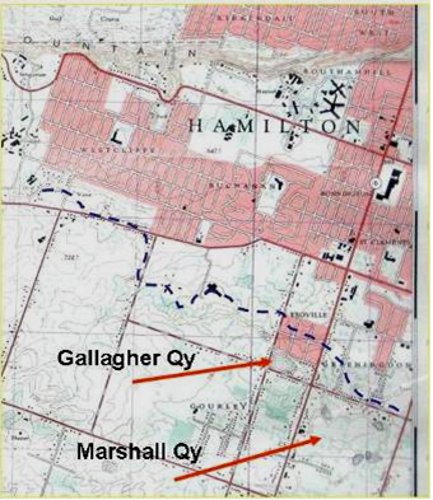

The Eramosa member of the Lockport Formation is not generally exposed at the crest of the escarpment, because the lower part (above the Ancaster chert beds) is shaly and weathers back. The upper, dolomitic part is resistant and forms its own small escarpment (where it is not obscured by glacial drift). Figure 1 is a map showing the escarpment on the Mountain, and the location of two of the largest quarries.

Figure 1. Map showing location of two quarries in the Eramosa dolomite: The Marshall quarry was first developed in the 1850s: neither quarry produced much building stone after 1900. The heavy dashed line indicates the Eramosa escarpment.

The Eramosa escarpment is more prominent in Ancaster. It is clearly shown on the Dundas Valley conservation map (Figure 2). Source

Figure 2. Map of the northern part of Ancaster, showing the location of the Niagara and Eramosa escarpments. The old quarries were located along the edge of the Eramosa escarpment on both sides of the present Wilson St (Highway #2).

The old quarries can still be seen in Ancaster (Figure 3), but have been built over in Hamilton. A few outcrops of Eramosa can still be seen in the Eramosa Karst Park and can be seen (in passing) on the Linc (Figure 4).

The transition from the shaly lower part of the Eramosa to the upper dolomite can be seen clearly in the stream bed at the Ancaster Old Mill (Figure 5). This section was described briefly by Tom Bolton in his 1957 publication (Geological Survey of Canada Memoir 289): "Eramosa: Dolomite; brown, dense, thin bedded, petroliferous; grey and black, bituminous shale partings; upper 20 feet more massive; top three feet one solid band (possible Guelph equivalent). 43 feet."

Below the exposed Eramosa there was no exposure for an estimated 55 feet, before reaching the Ancaster Chert beds in the roadcut. The total Lockport thickness was about 140 feet.

Figure 3. Eramosa in an Ancaster quarry, just N of Ontario St.: the green hue is due to mould on the rock.

Figure 4. Eramosa outcrop on the Linc near James St Exit. White scale is 8cm long.

Figure 5. Eramosa exposed in the bed of Ancaster Creek: the Eramosa escarpment produces the small waterfall seen just upstream of the Old Mill Restaurant.

The Eramosa was used as a building stone in Ancaster some years before it was used in Hamilton. The reason was that it is a fine building stone there (better than in Hamilton) and Ancaster had no access to Whirlpool sandstone. It was used in fine buildings from 1828 to the 1870s, but particularly after the arrival from England in 1855 of an accomplished stone mason, George Guest.

Figure 6: Mountain Park was built in 1828 by a Hamilton lawyer, Robert Berrie, and extended by later owners, including the Robb family. The stone work could be described as squared random rubble.

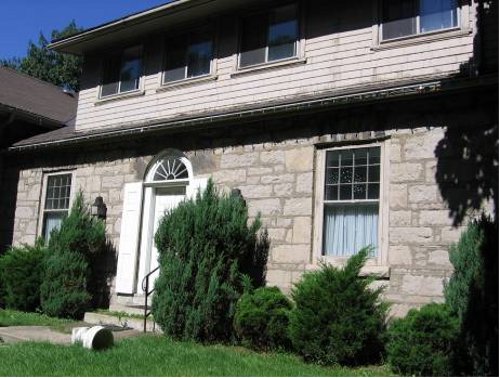

Figure 7: The Kelly House, on Old Dundas Road, was built in two parts: the lower story in 1845, and the upper part and façade in the late 1850s, after George Guest arrived from England. The stone work on the façade is near-ashlar. Note that the window sills (somewhat blackened) are Whirlpool sandstone.

Ballinahinch may have been the first large building constructed from Eramosa from the Mountain, but it is hard to be sure, because it was rebuilt after a fire in 1853 and was modified in the 1870s. Hereford House on Bold St was built of both Eramosa and Whirlpool in 1856 (Figure 8). A good description and photos are given in Shaw and Crankshaw's book Heritage Treasures (2004, p.91).

The Hamilton Waterworks built in 1859 is an excellent example of the industrial use of Eramosa. The terrace at 120-122 Hughson Street South, built in 1860, also used Eramosa (Figure 9).

The first major public buildings built of this stone, however, were churches: Carisma Church (built in 1869 as St. John's Anglican) and its manse; All Saints built in 1873; St Patricks, built in 1873; and the James St Baptist Church built in 1883. The last two were designed by Joseph Connelly: see Malcolm Thurlby's article Two Churches.

Figure 8. Eramosa and Whirlpool used in Hereford House, 13-15 Bold St. The cut and hammered finish of the grey Whirlpool quoins and course contrasts with the weathered brown surface of the Eramosa blocks.

Figure 9: The terrace at 120-122 Hughson Street South, built in 1860 from regular courses of trimmed blocks of Eramosa from the Mountain.

St Patrick's Church is particularly interesting, not only for its architecture but also for its use of a variety of imported stones, besides the Eramosa (Figure 10).

Figure 10. The entrance to St Patrick's Church: the main stone is Eramosa dolomite from the Mountain, but the trim (on the main door) is mainly imported Ohio sandstone.

Ohio sandstone, also known as Berea Sandstone was used in several other Hamilton buildings, including the Customs House (1861), Christ's Church Cathedral (the original chancel and church, 1852-4, where is badly blackened), and late additions to Central School.

Its advantages are its pleasant golden brown colour (when fresh), and the fact that it is softer and easier to carve than the Whirlpool sandstone. For this reason it is often used for doorways and small grotesque heads, called beakheads. Examples of its use in doorways include St Paul's in Hamilton, and St John's in Ancaster. In St Patrick's it was also used for the large interior pillars, now (unfortunately) totally obscured by grey paint!

The Eramosa dolomite is quite variable in character, even that from Mountain quarries. Example close-ups are shown in Figure 11. The irregular bedding and texture, and presence of small cavities, called vugs (and see D in the figure) make it hard to trim the stone into regular blocks and almost impossible to produce a smooth finish.

But does this make it a less attractive building stone? We now value the warm colours and interesting weathered textures more than people did in the nineteenth century, before the invention of modern concrete.

Figure 11. Close-ups of Eramosa from four Hamilton buildings: A. Ascension Church Hall; B. Carisma Church; C. Christ's Church Cathedral Hall; D. James St. Baptist Church.

Eramosa dolomite was also quarried and used, with Whirlpool sandstone, for buildings in Waterdown. The Waterdown Eramosa contained more clay, and so it weathered more rapidly than the better Hamilton varieties. It nevertheless made an attractive building stone (Figure 12).

All the local varieties of Eramosa are fine grained and contain very few fossils visible to the naked eye, though they do contain some microfossils (studied by Jim Teeter in an unpublished thesis at McMaster, 1972).

This does not necessarily mean no organisms lived in the sea in which the original carbonate muds were deposited: in fact, the original irregular textures seen in the Hamilton and Waterdown varieties were produced by intense burrowing by organisms: geologists describe this as bioturbation. Unlike the Hamilton and Waterdown varieties, the Ancaster Eramosa shows almost no bioturbation so the stone could be trimmed to near ashlar perfection (Figure 7, Figure 13).

A final note on the Eramosa as a building stone: The stratigraphic unit extends along almost all of the Niagara escarpment in Ontario. In recent years it has been extensively quarried near Wiarton in the Bruce peninsula.

Since the main dolomite buildings stones in the Niagara peninsula have now been worked out (though quarries still produce crushed stone), the Wiarton quarries are now the main source for dolomite building (and paving) stone.

Wiarton stone was recently put to good use in building the new church hall for St. John's in Ancaster. A side benefit is that the Wiarton Eramosa has yielded a remarkable new discovery of well-preserved fossils.

Figure 12. Close-ups of Eramosa from Waterdown (left) and Ancaster (right). A. 298 Dundas St E, Waterdown; B. Ancaster Old Mill; C. Scout Hall, Waterdown; D. 21 Halson St., Ancaster. This fine house was originally the St. John's Church manse: the photographer's helper is Jesse, one of its present inhabitants.

Figure 13. Bethesda Church, Ancaster. Note the regularity of the Eramosa blocks and their hammered finish. The window sill and projecting course are Whirlpool sandstone.

By TnT (registered) | Posted August 23, 2011 at 17:23:48

This is fascinating. Is allows me to speculate the age of my property and type of stone. It looks just like the above pictures.

Also, would this type of stone be considered an eco option vs concrete? What type of mortar was used to hold these together, since modern additives didn’t exist?

By GerryM (registered) | Posted August 23, 2011 at 18:31:04 in reply to Comment 68398

When it comes to basements, the main question is what stands up to damp. Bricks are not so hot, field stone is usually fine: the right mortar was rediscovered when the Erie canal was built. Modern concrete is fine; I would be reluctant to recommend Eramosa rubble, but if it has already lasted 150 years, why not?

Fieldstone from the Shield is not common in Hamilton (but see the basement of Battlefield House in Stoney Creek) but it was used extensively in Galt and Waterloo.

Comment edited by GerryM on 2011-08-23 19:59:25

By TnT (registered) | Posted August 24, 2011 at 00:39:07 in reply to Comment 68399

When speaking of moisture in basements, from my expirence with my basement, it doesnt leak when it rains. However, in the next few days moisture appears, then kind of gets sucked back into walls. Is it to do with type of stone? It certainly couldnt be used as finished space, like modern concrete ones.

By NortheastWind (registered) | Posted August 23, 2011 at 21:55:45

Although likely for aggregate and not for building stone, there were once quarry's close to the TH&B rail line on the south mountain. I used to swim in one of them as a kid. I see that the one just off of highway 53, north between Pritchard and Darnell has recently been modified. Does anyone know what they did? It is was already a water retention pond for runoff from Rymal Rd, Was it part of the solution to flooding on the expressway. The tributary to the RH Creek that is next to the quarry has flooded during many a spring, right over Stone Church Rd.

Comment edited by NortheastWind on 2011-08-23 21:59:01

By rednic (registered) | Posted August 24, 2011 at 07:04:00

Thanks for these articles. Writing and publishing this kind of info is what make the 'net great quite frankly!

By heritage (anonymous) | Posted August 24, 2011 at 18:23:58

The first mortars were lime based. We know now that lime mortars used in the 19th century were softer than the stone or brick of the stucture being constructed and that the mortar was able to allow for the passing of water vapour through the seasons. Two critical properties that allow older buildings to survive today. It is very unlikely that water will become entrapped within these older materials.

It is a mistake to use modern portland based cements that are harder than the old stone or brick in historic buildings. Water vapour or moisture in the air is not allowed to pass through portland and the building stone or brick will break before the cement when any very minute seasonal shifting occurs in the building. I have seen the resulting broken building stone when water becomes trapped behind portland based mortars and the freeze thaw cycle blows it apart.

Buildings always move and seasonal humidity will try to equalize itself in buildings. They need to breathe.

The crafts people that built our historic buildings knew that they needed to work with the natural environtment.

By Pxtl (registered) - website | Posted August 25, 2011 at 09:27:24

I'm sorry, I can't take this article seriously because I keep thinking that Eramosa Dolomite sounds like some kind of '70s action hero.

By TnT (registered) | Posted August 25, 2011 at 11:15:46

I had a mason work on my property and he made some comment about needing older mortar to patch the base. I didn't pay attention, I just paid him. However, after reading this it sounds like that was the purpose.

By GerryM (registered) | Posted August 25, 2011 at 12:20:01

Yes, old stone work does need to be re-pointed from time to time, i.e., to have the surface mortar that has started to weather replaced; and it is essential not to use modern cement

As regards basements (and also canal and harbour works in stone) it was necessary to use a cement that can harden under water -- a trick known to the ancients (Romans in particular) but lost for hundreds of years -- re-disovered in England and in US for construction of the Erie Canal (1817-1825), and in Canada used for the second and third Welland canals (built 1841-1887) and the Rideau waterway (1838-?). Portland cement was not introduced in Canada until 1889. Concrete blocks were manufactured here since 1907. W.F. Gibson used concrete blocks in 1912 to construct a house in Grimsby.

Comment edited by GerryM on 2011-08-25 12:21:15

By Jonathan Dalton (registered) | Posted August 26, 2011 at 10:57:42

Here's another way of maintaining a stone heritage building - stucco it and save a few dollars.

This is happening to a house in Kirkendall neighbourhood, and I am trying to have bylaw stop the work. It would be a terrible loss.

By highwater (registered) | Posted August 26, 2011 at 12:17:42 in reply to Comment 68436

I hope you're not the only one. You should get the neighbourhood association involved. What a travesty.

By TnT (registered) | Posted August 28, 2011 at 09:46:02

Is the purpose of stucco here for insulation value? As above stated old stone lets moisture vapor in and out. Would stucco and foam over stone really damage the structure of this house?

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?