Most early stone buildings in Hamilton were constructed from two local stones: a sandstone quarried at the base of the escarpment, and a dolomite quarried on the Mountain. This article gives the geological background, describes the two stones, and the his

By Gerard V. Middleton

Published August 18, 2011

In the nineteenth century, most fine buildings in Hamilton were built from two locally quarried stones: sandstone from quarries near the base of the Mountain, and dolomite from quarries on the Mountain. Both were used in the Pumphouse, constructed in 1859. For its history, see Hamilton's Old Pump House; for more photos see Historical Hamilton.

Figure 1: The Hamilton Waterworks: the stone at the base of the chimney is sandstone; the main building stone in the pumphouses is dolomite.

Generally, sandstone was the preferred stone for fine buildings, and was used in Hamilton from 1806 to the end of the 1850s. Only in the 1860s to 1880s was dolomite extensively used.

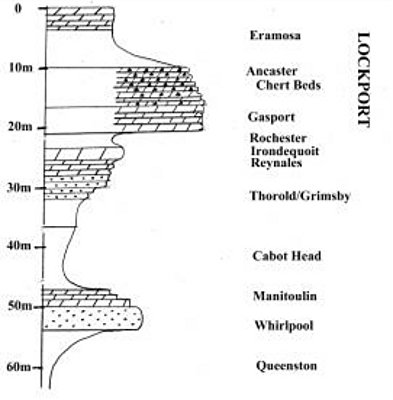

Where did the stone come from? The face of the Hamilton mountain, part of the Niagara escarpment, exposes the sedimentary rocks which were used to build Hamilton. Figure 2 shows a vertical section through the rocks which make up the escarpment.

Figure 2: Vertical section through the rocks (dots indicate sandstone, brick ornament is dolomite).

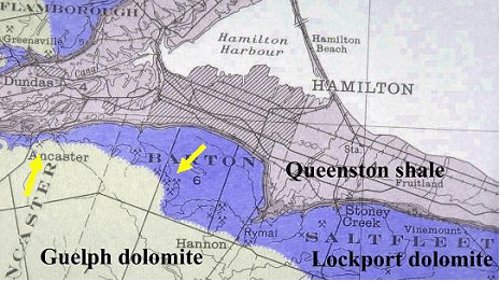

Near the base of the escarpment is the Whirlpool sandstone (named for the Whirlpool in the Niagara Gorge). It was quarried at several places in Hamilton and in Dundas. Figure 3 is a geological map, showing the outcrop of the Lockport dolomites in blue.

Figure 3: Geological map showing the outcrop of the Lockport (in blue). Yellow arrows indicate location of quarries in the Eramosa (crossed hammers).

The Lockport is divided into three units: the Gasport, the Ancaster Chert Beds, and the Eramosa. Only the Eramosa made a good building stone near Hamilton, though the Gasport produced an excellent stone in the Niagara area (the Queenston stone). For details on the local stratigraphy, see The Jolley Cut: Virtual Field Trip [PDF] and for more information on Niagara geology see Niagara Rocks, Building Stone, History and Wine [PDF].

The early city of Hamilton was built below the escarpment on the Queenston shale, and there were few good access roads up the escarpment until the mid 1850s. Most of the early buildings were built from the Whirlpool sandstone because:

So what is dolomite? Though commonly called "limestone", it differs from true limestone in important respects:

To tell the difference, test with a drop of acid: limestone fizzes, dolomite does not.

Figure 4: Whirlpool ashlar, in "The Castle" (now hidden behind the terrace at James St. South. Built in 1840).

Figure 5: Whirlpool sandstone ashlar (Rastrick House, 46 Forest Avenue; built in 1847).

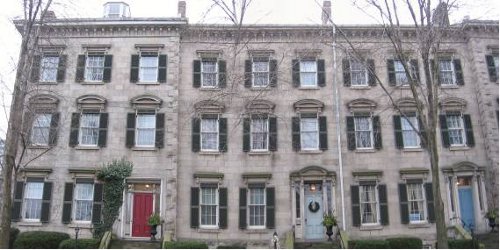

Figure 6: The James St. South stone terrace, built 1856-1860. This is only one of many such terraces built about that time from Whirlpool sandstone (in both Hamilton and Dundas).

Figure 7: Sandyford Place, built in 1856-1864 - the finest terrace in Hamilton built of Whirlpool sandstone.

Compact sandstones, like the Whirlpool, are subject to "black soiling" when exposed to industrial pollution. Good examples can be seen in downtown Hamilton (and also on Hatt St in Dundas). For examples from Scotland, where sandstone was extensively used as a building stone, see Cleaning Sandstone: Risks and Consequences.

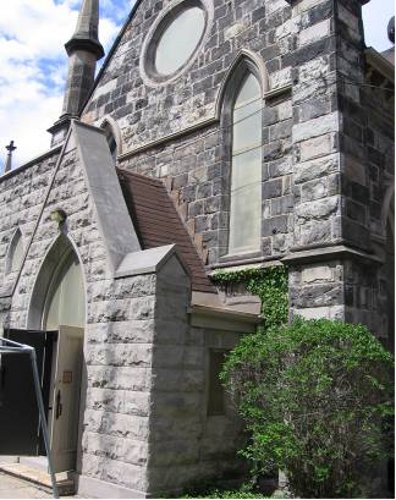

Figure 8: Church of the Ascension. Note the contrast between the grey stone of the entrance (added later and made of Eramosa dolomite) and the blackened Whirlpool sandstone used to construct the original church in 1851.

The Whirlpool sandstone was the most prized building stone in early nineteenth century southern Ontario. It was almost certainly used for Belleview, built in 1806 by James Durand and sold in 1815 to George Hamilton, and for the Gore District Courthouse built in 1832, Westlawn in 1836, the Gore Bank in 1840, the Bank of Upper Canada in 1856, and Arkledun in 1846 (all later demolished). Probably it was also used in the original Lister block (1852, destroyed by fire). It was also used to construct Darnley Grist Mill (1811) and Springdale (c. 1810) in West Flamborough, as well as many fine buildings in Queenston (1820s) and Dundas (1840s).

Surviving buildings in Hamilton include: the "Castle," Rastrick House, "Rock Castle," and Whitehern - all large homes built before 1850-the James Street, John St and Bold St terraces, built in the 1850s, the original Central School (1853), and three churches: Church of the Ascension (1851), St Pauls (1857), and MacNab Presbyterian (1857). Its value was recognized in the first major work on the Geology of Canada (1863) by William Logan.

In Hamilton and Dundas, the local Whirlpool sandstone ceased to be used as ashlar in the 1860s, because the local quarries were mostly worked out. It continued to be extensively used in smaller quantities for lintels and sills. After the construction of railroads in the 1880s, a new supply (from the Credit River Valley) became available.

Figure 9: The Durand house, built in 1806 at the base of the escarpment (and close to known quarries below the modern Jolley Cut). It was sold in 1815 to George Hamilton. The dangers of using the primitive roads up the escarpment were graphically described by Charles Durand in his [autobiography](http://www.archive.org/stream/reminiscencesofc00durauoft/reminiscencesofc00durauoft_djvu.txt). At that time, it was hardly possible to bring large loads of stone down from quarries on the Mountain.

In the second part, I describe the use of Eramosa dolomite from the Mountain, beginning with Carisma Church (1870), All Saints Church (1873), Christ Church Hall and School (1870), and Ascension Hall (1872). Thomas Connelly used Eramosa in St Patrick's and the James Street Baptist Churches, in the 1870s to 1880s.

By Undustrial (registered) - website | Posted August 18, 2011 at 10:28:09

Fascinating piece. I learned a lot.

I really have nothing to add except that the (Ancaster?) chert deposits in the west-end of the city were used even longer ago by local 'stone-aged' peoples for knapping tools. According to an old archaeology prof I had, you can still find it by the Dundurn stairs if you dare try your hand at it. The east end of the city, of course, holds evidence of some of the North American oldest settlements we know of.

By TnT (registered) | Posted August 18, 2011 at 10:50:22

Maybe not related, but when I purchased a house on Victoria in the past few years, the inspector called the foundation “field stone”. The property is aged around 1840s I believe. What would “fieldstone” mean?

By GerryM (registered) | Posted August 18, 2011 at 15:23:37 in reply to Comment 68174

Field stone means just what it says, stone collected from fields, not freshly quarried. In southern Ontario, most fieldstone consists of boulders left behind by the glaciers -- so much of it was granite and other Precambrian rocks derived from the Shield.

By TnT (registered) | Posted August 19, 2011 at 20:28:09 in reply to Comment 68217

What is the advantage, disadvantage, to this type of base as opposed to modern block, or concrete bases? I’ve added a Flick link photo of the basement I am talking about: http://www.flickr.com/photos/tntlockandk...

Comment edited by TnT on 2011-08-19 20:33:04

By Mr. Meister (anonymous) | Posted August 20, 2011 at 15:55:16 in reply to Comment 68289

That is not what I think of as field stone. Those stones look cut or shaped to me. When I hear field stone I think of this

http://www.advbasetech.com/images/stories/fieldbefore2.JPG

Or this

http://img.ehowcdn.com/article-page-main/ehow/images/a06/ke/ru/repair-leaky-fieldstone-basement-800x800.jpg

The stones are used literally the way they are found in the field. We used to live in a house built pre 1812 and the basement walls were 2' plus thick. Stones of every imaginable size from a few inches up to 2' x 3' x 3' were one stone was a chunk of the entire wall and weighed hundreds of pounds.

The advantage as explained to me was the availability of material and the sheer size and mass of the finished wall. I have a hard time imagining someone pushing over a freestanding fieldstone wall 2 or 3' thick, 8' tall and 20' long. Whereas a block wall of size could be pushed over without much difficulty.

By GerryM (registered) | Posted August 21, 2011 at 09:42:19 in reply to Comment 68305

I agree with Mr Meister, and his pictures are certainly of fieldstone. The picture by TnT is almost certainly of Eramosa dolomite from a quarry on the Mountain (it might possibly be Manitoulin from just above the Whirlpool). Anyway, more likely from a quarry than picked up from a field.

By TnT (registered) | Posted August 21, 2011 at 10:14:33 in reply to Comment 68316

Ah, does that give any idea the years this Eramosa was used? Oh, I see that it will be featured in the next article. Is it superior to fieldstone?

By Catherine (anonymous) | Posted August 18, 2011 at 11:45:16

Typo in the header, that would be escarpment, not escrapment... Great article, we sure love our stone house!

By misterque (registered) - website | Posted August 18, 2011 at 21:32:06 in reply to Comment 68187

Since the escarpment was created by erosion, escrapement doesn't seem like such a bad typo. :)

By stanley (anonymous) | Posted August 18, 2011 at 12:29:34

The castle...one of the finest stone buildings in Hamilton now a rooming house wedged behind that piece of garbage at James and Duke....if not for the quality of the materials it would probably be rubble.

By Jeff Tessier (anonymous) | Posted August 18, 2011 at 22:21:52 in reply to Comment 68198

I also lived there (it way my first apartment in the city when I moved here) and it's remarkable inside, even after being carved up. I think the 'piece of garbage' concealing it has actually, in a weird way, helped it stay intact because it's off everyone's radar.

By mystoneycreek (registered) - website | Posted August 18, 2011 at 15:08:19 in reply to Comment 68198

Ah, yes. 'The Castle'

I lived there years ago.

What a place, what memories...

By jonathan (registered) | Posted August 20, 2011 at 01:37:17 in reply to Comment 68214

Count me as another ex-Castle tenant. So...did any of you figure out that the foot-deep window frames actually concealed built-in shutters?

By mystoneycreek (registered) - website | Posted August 20, 2011 at 07:20:07 in reply to Comment 68293

Uh... Nope. That's fascinating. (I wish I'd taken photos.)

I lived there from about 87-91 in an apt facing north on the second floor. The tall ceilings, the fireplace... And the fact that it was this solid building from times-past made it a very special experience.

By slodrive (registered) | Posted August 18, 2011 at 12:32:38

Excellent piece, Ryan. Those are great shots.

By gd (anonymous) | Posted August 18, 2011 at 12:39:39

The photo of Belleview makes me sad - I live around the corner. What a loss to the neighbourhood!

By Robert D (anonymous) | Posted August 18, 2011 at 15:39:06

Very informative, thanks!

By adrian (registered) | Posted August 18, 2011 at 21:16:06

Fascinating article. I look forward to #2!

By Waterloo (anonymous) | Posted August 20, 2011 at 10:39:38

Regarding today's construction quality compared to the old stone buildings- The buildings that remain today might be the best of the time? Perhaps the Best of our time's construction would compare more favourably? When the Castle was built, how many people were living in terrible buildings, buildings that have since been destroyed.

By Undustrial (registered) - website | Posted August 21, 2011 at 09:06:38 in reply to Comment 68297

There certainly is a preservation bias at play, and it would be foolish to ignore it. On the other hand - not all the buildings that've been knocked down were the terrible ones.

There are a lot of reasons old buildings tend to be "better". Our city has changed a lot - new technologies have reduced the economic effects of distance - meaning that space doesn't need to be used as widely. The same could be said of energy, and so they can use climate control instead of thick, heavy walls and well-placed windows. We've cut down the old-growth forests that long-ago covered this area and others - meaning a drop in the quality of framing and other woodwork. And of course, construction is now much cheaper and easier, so buildings don't need to stand for a century before it's cost-efficient to replace them.

I could go on. Newer does not always mean better.

By TnT (registered) | Posted August 20, 2011 at 19:08:46

I was wondering if it would meet code today to build a modern structure with fieldstone basements like my old house?

By heritage (anonymous) | Posted August 21, 2011 at 10:00:30

The article is very good because it does hilight the way that our historic buildings were constructed and points out the craftspeople that were very skilled in building something to last forever. That extended from the masons and stonecarvers to the woodworkers, sash makers, plasterers, and many more artisans that lived in the communnity and were seeing and interacting with one another each day.

I am trained in these specialized skills and find it an educational process to explain to people that these materials that artisans have produced have lasted on their homes for 100 years and more. They have already proven their durability and that with a little help will continue to out out perform any modern material.

By Mark (registered) | Posted August 23, 2011 at 08:19:06

Sometimes I wish this style of home architecture would come back. We need less stucco and siding and more houses as depicted in Sandyford Place.

By mystoneycreek (registered) - website | Posted August 23, 2011 at 08:24:45 in reply to Comment 68358

Sometimes I wish this style of home architecture would come back.

Anyone with any experience/insight know what it would cost to do this? In comparison to what's commonly done?

As a cinema buff (I'm talking about the buildings now, the cathedrals, not the 'sermons'...) I know that constructing The Palace or The Capitol or The Century would be prohibitively expensive.

By Mahesh_P_Butani (registered) - website | Posted August 24, 2011 at 15:05:12 in reply to Comment 68359

The quality one admires in old low-rise/home stone masonry buildings may be difficult to replicate in our economy which is geared to low-cost/high margin, mass production -- where the term 'quality' is now synonymous with "custom work", a code word for high cost, stone-cladding and fake arches.

If you stand below load-bearing masonry arches you can almost feel the weight of the stones/bricks as you stand under them. Stand below the new "custom job" arches one sees all over nowadays and you will feel no weight above you. Try it out next time you pass an arch!

The old art of making load-bearing masonry building has simply faded away, and is replaced mainly with masonry work for surface cladding factory cut stones or bricks in homes and landscape work - which simply does not have the same feel of old masonry work.

Will such skills come back? I doubt it - given the economics of our construction industry. However, for those interested in contemporary masonry, there is a still a good career to be made in this field.

There is also the rare instance in North America of load-bearing stone masonry - a work-in-progress, affectionately called "St. John's the Unfinished", where new techniques to carve stone were adopted in an attempt to complete the work started in 1892.

Comment edited by Mahesh_P_Butani on 2011-08-24 15:06:10

By Undustrial (registered) - website | Posted August 25, 2011 at 09:38:06

I certainly would love to see more stone buildings, but the first question is: how much stone do we have? It isn't just the cost of the labour - think about what would happen to the price if even 1% of Hamilton got a fancy new stone house. I suppose the follow-up question would be: how much of the limestone which currently gets baked into cement is in large enough chunks and decent enough quality to use as building material straight.

The advent of concrete has been the great antagonist here. Why bother with masonry when you can cast limestone on site? Strange, now that we have jackhammers, concrete-saws and cranes on trucks, that stone building is no more possible than when we used mostly hammers, chisels and muscles. It says a lot about the way our technologies evolved. As industries developed, de-skilling the old workers was the main job of new machines - especially when the field had previously been dominated by powerful, organized blocs of workers like the masons.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?