For this year's annual Doors Open Hamilton, take the opportunity to learn about two nineteenth century Hamilton churches.

By Malcolm Thurlby

Published April 21, 2006

On Saturday and Sunday, May 6 and 7, Hamilton celebrates its 4th annual Doors Open. Of the 44 buildings open to the public for this occasion, two churches designed by the Irish-trained, Toronto-based architect, Joseph Connolly (1840-1904) hold special places in his oeuvre.

St Patrick's Roman Catholic, King Street East at Victoria Street, 1875-77, is the only Connolly church to preserve its original presentation drawings. They will be on display at the church between 10am and 4pm on Saturday. It is also in the design of at St Patrick's that Connolly's Irish Gothic architectural heritage is especially evident. James Street Baptist, James Street South at Jackson Street, 1878-82, is the only church designed by Connolly for a non-Catholic patron.

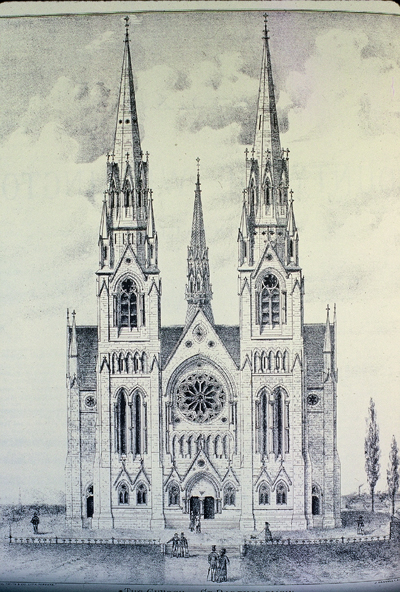

Fig. 1. Hamilton, St Patrick's Roman Catholic Church, façade, Joseph Connolly, 1875-77

Connolly's architectural credentials were of the highest order. Born in Limerick, he received his training in the Dublin office of James Joseph McCarthy (1817-81). McCarthy specialized in work for the Roman Catholic Church, and was one of the most celebrated architects in 19th-century Ireland.

Connolly advanced to become McCarthy's chief assistant in the late 1860s. He subsequently made a study tour in Europe, and in 1871 he was in practice in Dublin for himself, although no records survive of any commissions. By 13 August 1873 he had moved to Toronto, where he entered into partnership with the engineer, surveyor, and architect Silas James. This association was dissolved by 23 April 1877, after which Connolly practised alone.

Fig. 2. Kilcullen (Co. Kildare), St Brigid's Roman Catholic Church, façade, J.J. McCarthy, 1869.

Over the next 25 years he designed or remodeled nearly forty Roman Catholic churches and chapels in Ontario, plus the Roman Catholic cathedral in Sault-Sainte-Marie (Michigan). His Irish background made him the ideal person to design St Patrick's church for the Irish Catholic community. That he secured the commission for James Street Baptist church is perhaps a little surprising. However, as we shall see, Connolly's ability to create monumental, cathedral-like structures must have impressed a building committee intent on ensuring a strong architectural expression of the Baptist presence in town.

St Patrick's is built in the Gothic style that was first used shortly before 1140 in the abbey church of Saint-Denis, just north of Paris. Characterized by pointed arches, slim pillars and stained glass windows, the style spread throughout Europe by the end of the 12th century.

With the revival of classical Roman forms in the Italian Renaissance in the 15th and 16th centuries, Gothic fell out of favour. It regained popularity in the early 19th century and found a great champion in the English architect and theorist, Augustus Welby Pugin (1812-1852).

Pugin was passionate about Gothic, or Pointed, architecture as he called it. For him it was the only appropriate style for church building. Gothic was Christian, and quite the opposite of the Classical tradition in architecture associated, as it was, with the pagan gods of ancient Greece and Rome. Pugin's many publications, such as The True Principles of Pointed Architecture (1841), argued for the careful study of Medieval Gothic buildings as the basis for an accurate revival of the style and constructional techniques of the Middle Ages.

Fig. 3. Kilcullen (Co. Kildare), St Brigid's Roman Catholic Church, detail of stained glass, St Brigid presenting a model of the church to Christ.

In Ireland, Pugin's principles were so enthusiastically adopted by J.J. McCarthy that he was called the 'Irish Pugin'. Two of McCarthy's early churches, St Kevin at Glendalough (Co. Wicklow) (1846-49), and St Alphonsus Liguori, Kilskyre (Co. Meath) (1847-54), even received the rare distinction of a positive review in the high-church Anglican publication, The Ecclesiologist, principally because they "imitate ancient models".

McCarthy soon assimilated the rudiments of Irish Medieval Gothic design and, in so doing, began to interpret, rather than simply imitate, his models. This is well illustrated in his 1853 design for St Patrick's, St John's, Newfoundland, in which he demonstrated both a command of Irish Medieval sources and a thorough knowledge of A.W. Pugin's Irish churches.

By the 1860s, in keeping with contemporary progressive architects in England and Ireland, he was attracted by the early Gothic of northern France, and included such references in his work. McCarthy's church designs had a profound impact on Connolly's work in Ontario, and not least in St Patrick's, Hamilton.

The foundation stone of St Patrick's was laid on Sunday, June 27, 1875, and the church was opened just over two years later, on Sunday, July 1, 1877. The design of the churches speaks clearly of Connolly's Irish background. The basic model is St Brigid's, Kilcullen (Co. Kildare) built in 1869 to the design of J.J. McCarthy. This was the very time when Connolly was chief assistant in McCarthy's office.

Comparison of the entrance facades of the two churches makes the relationship clear (Figs 1 & 2). The pointed doorway is flanked by two roundels set beneath pointed arches. Above, a statue is set between pointed, two-light windows, and is surmounted by a gabled canopy. In the gable there is a large rose window which is topped with a pointed enclosing arch.

In both buildings, the basic building material is rough, hammer-dressed stone with smoothly finished stone largely reserved for the doorway and windows. The façade is divided vertically into three units by stepped buttresses. These provide support for the walls and express the internal division of the church with a central nave and an aisle to either side.

Fig. 5. Monaghan Cathedral, N nave exterior, J.J. McCarthy, 1861.

St Patrick's boasts an angle tower to the façade and this feature was originally intended for St Brigid's. This is illustrated in a stained glass window at St Brigid's in which the angle tower was to be surmounted by a spire, just as Connolly planned for St Patrick's (Figs 3 & 4). Connolly's drawing also shows a polygonal baptistery projecting to the left of the façade, a feature lacking at St Brigid's but used elsewhere by McCarthy, as at Monaghan Cathedral (1861) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 6. Hamilton, St Patrick's Roman Catholic Church, interior.

In light of the similarities between St Patrick's and St Brigid's discussed so far, it will come as no surprise that the interior of both churches are closely related (Figs 6 & 7). Both have two-storey elevations in the nave with a pointed main arcade carried on cylindrical columns topped with symmetrical foliage capitals, and each arch is surmounted by paired clerestory windows.

There is a paneled timber roof in which the principal rafters rest on wall posts set above the columns of the main arcades. The high altar is located in the sanctuary, the entrance to which is marked with a tall arch, built in stone at St Patrick's rather than in wood at St Brigid's.

Fig. 7. Kilcullen (Co. Kildare), St Brigid's Roman Catholic Church, interior.

The spaces are further differentiated by a step up from the nave floor to the sanctuary and with the use of larger windows in the sanctuary to admit more light to the area around the high altar. There are also differences between the two designs.

The proportions of St Patrick's are taller, indeed more satisfactory, than at St Brigid's, but it seems that the price for this was that the polished granite shafts of the main arcades at St Brigid's were not reproduced at St Patrick's.

Fig. 8. Hamilton, St Mary's Catholic Church, (formerly Cathedral), interior.

The interior of St Patrick's is quite distinct from that of St Mary's, the former Roman Catholic Cathedral in Hamilton, built between 1859 and 1860 (Figs 6 & 8). Both have pointed Gothic arches that sit on richly carved capitals atop the arcade piers, but the similarities end there.

St Mary's has a single-storey elevation and is covered throughout with pointed vaults. Here the design is inspired by Santa Maria sopra Minerva, the only Gothic church in the city of Rome. The model is a very logical one for St Mary's and many other Catholic churches in Ontario, in that the pointed elements of the Christian Gothic style advocated by Pugin are now specifically associated with the home of the Roman Catholic church.

Be that as it may, there are two features in St Mary's that would have been unacceptable to Pugin. The piers and arches of the main arcades are built of wood in imitation of stone, and the vaults are lath and plaster, again imitating medieval originals in stone. Pugin spoke out strongly about such mimesis. Materials were to be used truthfully, as he believed they were in the middle ages. Wood should appear as wood and should not be plastered or painted to masquerade as stone.

As a follower of Pugin, Connolly abided by such principles. St Patrick's introduces truthful Gothic design with clear Irish references as entirely appropriate for its Irish congregation.

Fig. 9. Hamilton, James Street Baptist Church, façade, Joesph Connolly, 1878-82.

Such specific Irish Catholic associations would hardly have impressed the building committee of James Street Baptist Church when they hired Joseph Connolly to design their church. The grandeur and fine proportions of St Patrick's church, on the other hand, would have influenced the committee.

Fig. 10. Guelph, Church of Our Lady (formerly St Bartholomew), façade as planned, from Waterloo and Wellington County Atlas (1877).

It is also likely that they would also have known of Connolly's Church of Our Lady (formerly St Bartholomew) at Guelph, on which work had commenced in 1876. This huge, cathedral-like edifice was built to rival, indeed surpass, the recently completed Anglican church of St George (1870-72).

Such architectural rivalries were commonplace in Ontario towns and cities in the 1870s and 80s. And, it is in this context that James Street Baptist Church must be seen. Quite apart from competing architecturally with St Patrick's, the new Baptist Church could not be in any way inferior to St Paul's Presbyterian (1854-57) located immediately across the road to the north.

Christ Church Anglican Cathedral (252 James Street North) had been completed in 1873 by Toronto architect, Henry Langley, of Langley, Langley and Burke, and in 1874 the Zion Tabernacle was built for the Methodists (69 Pearl Street North) to the design of Joseph Savage from Montreal.

Fig. 11. Hamilton, Zion Tabernacle, exterior, Joseph Savage, 1874.

In Toronto, Henry Langley's Metropolitan Methodist church (1870-73) was dubbed the 'Cathedral of Methodism', and its Presbyterian rival was the New St Andrew's by William George Storm (1875). The monumental Jarvis Street Baptist Church in Toronto, by Langley, Langley and Burke, was also completed in 1875.

In this climate of denominational and civic one-upmanship, the design of James Street Baptist Church had to come up to par.

For the façade, Connolly adapted the front of his new church in Guelph, which in turn owed much to Cologne Cathedral in Germany (Figs 9 & 10) and French 13th-century Gothic cathedrals. Buttresses provide a three-part vertical division which, as at St Patrick's, corresponds with the separation of the interior space into the nave and flanking aisles.

Fig. 12. Hamilton, James Street Baptist Church, exterior.

The main entrance has a pointed arch on polished granite shafts and is set within a projecting gable. Lower gables surmount the windows to either side of the entrance. Above this at Guelph, there is a row of pointed blind arches and a rose window within the pointed enclosing arch.

This composition is metamorphosed at James Street Baptist into a vast pointed window with six lower lights (subdivisions) and an elaborate pattern above known as geometric bar tracery. Such windows were the norm in English cathedrals and great monastic churches from the mid-13th century on.

Fig. 13. Guelph, Church of Our Lady, exterior.

The twin towers of Guelph are reduced to one for the James Street church. Such an economy would have been deemed acceptable given the use of single towers at St Paul's Presbyterian, St Patrick's and at the Zion Tabernacle (Fig. 11). Moreover the façade of Christ Church Anglican Cathedral was completed without towers.

The side elevation of James Street Baptist Church also reflects Our Lady at Guelph (Figs 12 & 13). Both churches are raised on a full basement and have a prominent transept – the tall, gabled projection just to the right of centre in each photograph.

Transepts were a standard feature in Medieval Gothic cathedrals positioned to either side of the church at the junction of the sanctuary and the nave. Their inclusion at Guelph made sense from a functional point of view – in the photograph the semi-circular projection on the right of the transept housed a minor altar.

Fig. 14. Hamilton, James Street Baptist Church, interior.

To the right in the photograph, we see the tall clerestory windows of the sanctuary that illuminate the high altar, and a series of polygonal chapels that radiate from the ambulatory each of which had a separate altar. The Baptists had no need for multiple altars and therefore the ambulatory plan with radiating chapels was abandoned in favour of a short, rectangular space for the baptistery, organ and choir, from which the pulpit projected towards the congregation (Fig. 14).

Strictly speaking there was no pressing need for the transepts but they did, of course, provide increased monumentality to the exterior of the building, so desirable for a Baptist 'Cathedral'.

The interior of James Street Baptist Church is divided longitudinally into a nave and aisles like St Patrick's. The two-storey elevation is also similar in the two churches, even to having similar foliage capitals based ultimately on French early Gothic exemplars (Figs 6 & 14).

At the James Street church, polished pink granite is used for the shafts of the main arcade pillars and wooden vault cover the nave and aisles. Here it should be emphasized that Connolly uses the wood truthfully, and that it is not plastered and painted in imitation of a masonry vault.

Fig. 15. Hamilton, James Street Baptist Church, interior from aisle.

Grand as the interior appears, the division of space into a nave and aisles is not well suited to the Baptist service. The arcade pillars obstruct the view of the pulpit from the aisles (Fig. 15). While the seating is arranged in a series of arcs, the shallow curvature is far removed from the full amphitheatrical configuration in use elsewhere in Baptist, Methodist and Presbyterian churches at the time.

In such churches, a square interior space was adopted in preference to the longitudinal nave and aisles of the Medieval Gothic tradition used by Connolly. This facilitated the placement of seats closest to the pulpit platform in a complete semicircle while those further away followed in a set of concentric arcs.

This system was used in Jarvis Street Baptist Church, Toronto, and in the Zion Tabernacle in Hamilton. The latter has subsequently been reduced in scale but the central blocks of the original seats remain to this day (Fig. 16).

Whether or not such progressive designs were considered by the James Street Baptist Church building committee is not known. But even if they were, the committee was more impressed by Connolly's Baptist 'Cathedral'.

Fig. 16. Hamilton, Zion Tabernacle, interior.

By (anonymous) | Posted April 22, 2006 at 20:16:09

Thanks to the IndyMedia for this great article on Hamilton's architecture. Doors Open is totally organized by volunteers. For full info re. 2006 visit www.architecturehamilton.com

By Jacobs (anonymous) | Posted June 04, 2013 at 13:33:21

Magnificent worship centres, please do not sell to developers but to other Christian organisations only, we need to preserve these places for the glory of our God.

Let the people worship in Truth and Spirit, that means let the people be filled in the Holy Spirit and the Churches will be back to life, it is not tradition, but truth shall prevail, I will Build My Church and the Gates of Hell Shall not prevail.

Youth need energy not boring sermons, they can see through you easily, how hard you try to hide truth it will be seen in your face, so seek God first and have a first hand experience with God. Let us pray for the anointing of the Holy Spirit to run churches, there must be an Azusa Street revival in Canada, an Upper Room experience like that of the First Century, 120 filled with holy spirit and spoken in other tongues and sings and wonders start manifesting, apostles went out with boldness and preached the Gospel. not the false one but the true Godly revival. God bless all Canadians, for a million immigrants from other faiths are over taking our part, if we shy it will all be gone for ever.

By Sgreenovich (anonymous) | Posted June 27, 2013 at 13:35:45

Those stained glass windows are always amazing, I keep wondering what would happen if Langley windows tried something like that.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?