Should the fate of this internationally significant building be left in the balance, or should all levels of government be pro-active in saving this jewel of our architectural heritage?

By Malcolm Thurlby

Published July 27, 2009

Located at 13 Burwell Street, across the road and to the southwest of St James's Anglican church, the former Paris Town Hall is a building of international significance in the history of civic Gothic architecture (Figs 1-3).

In sharp contrast to the 18th-century Gothic tradition of the nave of St James's Anglican church, the Town Hall incorporates details from medieval Gothic exemplars, and shows that the architect, John Maxwell (1803-1889), not only was up to date with the architectural theory associated with the Gothic Revival in England, but was in advance of even the most progressive English architects in the use of the Gothic style for a major civic building.

Fig. 1. Paris Town Hall and St James's Anglican Church (Paris Museum and Archives).

Fig. 2. Paris Town Hall, exterior from NW.

Fig. 3. Paris Town Hall, exterior from NW (Paris Museum and Archives postcard).

A committee to report upon a suitable site for a Town Hall was formed on 7 February 1853. On 21 February it was reported that there was a proposal for a site suitable for the Town Hall and Market "from the proprietors of Lot No. 7 and half of No. 6." John Maxwell is recorded as the architect, and Gardner and Strickland, contractors tendered for £1957, "the building to be finished on the first January next".

At the Council Meeting of 23 June 1853 it was moved "That By Law to raise by way of loan the sum of Two thousand Five Hundred Pounds payable in Twelve years for the purpose of purchasing a site and erecting a Town Hall and Market and other Public buildings do now pass". The motion was carried.

On 19 December 1853 a By Law was passed "to raise by way of Loan the sum of £900 for the purpose of finishing the Town Hall and Market and for the purchase of a fire engine".

According to the Brant County Gazetteer and Directory, the cost of the building was about $12,000.

John Maxwell was born on 24 May 1803 at Kilmadock, Perth, Scotland. He registered as a Provincial Land Surveyor on 23 January 1849, and later advertised himself as a "Surveyor & Architect" in Hamilton, Ont. He is listed in the 1851 Census of the Village of Paris, as a Civil Engineer, born in Scotland, age 37, with a one-and-a-half storey frame office, and of Roman Catholic religion.

Also listed is his wife, Canadian born, age 34, and children, Robert, age 11, Francis, age 8, May, age 6, and Joseph, age 4. On 24 October 1851 John Maxwell placed an advertisement in the Paris Star and Great Western Advocate, as Civil Engineer, Architect, Provincial Land Surveyor, Upper Village Paris. Research to date has revealed nothing of Maxwell's training.

The Market House and Town Hall, as it is described in the 18-page Specifications written by John Maxwell, has a rectangular plan on an east-west axis with north and south wings and a tower in the northwest angle for the north wing and the hall.

It has two-and-a-half storeys with a partial basement in which the eastern two thirds are divided into six equal aisles by squared wooden columns (Fig. 4). This area served as the 'lower market' and was entered through a four-centred brick arch at the east end (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. Paris Town Hall, basement, interior to E.

Fig. 5. Paris Town Hall, basement, interior, blocked E doorway.

The western third of the basement included prisoners' cells. The ground floor, which is divided longitudinally into three aisles with wooden columns, served as the market hall, with the council chamber and Magistrate's and Treasurer's offices at the west end (Figs 6 and 7). An archival photograph shows the original Gothic fenestration (Fig. 8). The vault adjoined the Treasurer's office immediately to the east of the doorway to the tower (Figs 7 and 9).

The stairs from the ground floor to the hall are located in the north wing. The upper story with its magnificent open timber roof served as the Assembly Room (Fig. 10). The lower section of the basement walls are constructed in stone while the superstructure is of brick with stone dressings.

Fig. 6. Paris Town Hall, ground floor, interior to ENE.

Fig. 7. Paris Town Hall, ground floor, interior to N.

Fig. 8. Paris Town Hall, Council Meeting with Andrew H. Baird, Mayor 1877-79 and 1896 (Paris Museum and Archives).

Fig. 9. Paris Town Hall, ground floor, vault.

Fig. 10. Paris Town Hall, Assembly Room, interior to ENE.

On the ground floor the walls of the council room and offices were plastered but the brickwork of the market was left exposed, a division that remains to this day (Figs 6 and 7). Moulded bricks articulate the doorways and windows, while wood is used for the tracery of the pointed windows of the four facades of the building.

The corners of the building are articulated with stepped angle buttresses with stone pinnacles and weatherings (Figs 1 and 2). A late 19th-century photograph shows that the octagonal clasping buttresses of the wings were topped with crenellated turrets (Fig. 1).

By the 1850s, Gothic had become the preferred style for church architecture in Ontario but this was certainly not the case with secular public architecture (on Gothic churches in Hamilton see: Two Churches by Joseph Connolly in Hamilton, More 19th Century Churches in Hamilton, First-Rate Gothic: A Look at St Paul's Presbyterian Church, Hamilton, and 19th-Century Churches in Hamilton: Barton Stone United Church and St Paul's Anglican Church, Glanford).

In the civic realm, the classical tradition prevailed with ultimate reference to Ancient Greece and Rome, often filtered through Renaissance, Baroque and/or Neo-Classical intermediaries.

Examples abound: George Browne's Kingston City Hall (1841-44), the Dundas Town Hall and Market by Francis Hawkins (1848-49), St Catharines Town Hall by Kivas Tully (1848-51), Guelph Town Hall by William Thomas, Napanee Town Hall and Market by Edward Horsey of Kingston (1856), Bath Town Hall (1866), and Victoria Hall in Cobourg by Kivas Tully (1856-60).

The unusual choice of the Gothic style for the Paris Town Hall is reported in an 1854 newspaper article published in The Times [London, ON]:

There is also a very substantial and excellent Market House and Town Hall, but the style is very remarkable being so strongly ecclesiastical that any stranger ill-informed to the contrary would at once pronounce it a church. It seems strange to find the tower of this costly edifice used perchance for hunters' stalls, and its chancel devoted to the dispensing of beef and mutton. But tastes differ, and if the Parisians are satisfied, that is the main thing.

Yet by 1859, Gothic was the chosen style for the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa. While Gothic was never destined to supplant the classical tradition for monumental public buildings in Canada, it is clear that Paris Town Hall marks a very significant moment in the history of Gothic architecture in Canada. Indeed, we shall see that John Maxwell was remarkably well informed on contemporary British practice and theory concerning Gothic architecture.

Gothic was not without precedent for public buildings in Ontario. In the first place there is the Middlesex County Building, London, Ontario, built between 1827 and 1831 to the design of John Ewart, with additions. Something similar is seen in Thomas Young's Wellington District Courthouse, Guelph (1837-44 with additions).

Both buildings belong to an 18th-century Castellated Gothic tradition which paid little or no attention to the study of medieval Gothic architecture. John Maxwell's approach to the design of the Paris Town Hall was quite different. He abandoned romantic 18th-century Gothicism in favour of precise reference to medieval architectural precedent through the medium of illustrations of details in the English architectural press.

The choice of the Gothic style for the Paris Town Hall has been seen as a way of distinguishing it from the Greek Revival mansions of the town's mill owners. This may have been a factor and it also sets apart Paris Town Hall from earlier and near-contemporary town and city halls in Ontario and government buildings elsewhere in Canada.

Gothic may also have been perceived as quintessentially English. Hiram Capron, founder of Paris, was born in Leicester, Vermont, but renounced his American citizenship in 1823 and swore allegiance to the Crown. There was also a strong desire amongst the 'upper crust' of Paris to adopt the etiquette of British society.

In light of this, it seems appropriate to seek British associations for the Paris Town Hall and what better precedent could there be for a Gothic public building than the Houses of Parliament in London? In 1834, fire gutted the Houses of Parliament. Rebuilding started in 1840 with Sir Charles Barry as the architect and Augustus Welby Pugin - the great champion of the Gothic revival in church architecture - providing the Gothic detailing.

Surprisingly, this did not give rise to a glut of Gothic government architecture. In a very influential book titled Remarks on Secular and Domestic Architecture: Present and Future, published in 1857, [Sir] George Gilbert Scott wrote:

Few things surprise me more than the neglect which pointed architecture has met with among the builders of town-halls. Next to churches, the finest of medieval structures existing are, perhaps, some of the town-halls of Flanders, Germany, France, and some of the free cities of Italy; yet scarcely an attempt has been made to revive these noble buildings in England, and town-halls are continually being erected in our provincial towns in styles as thoroughly unsuitable as can be conceived, and at a cost which would, in good hands and in a right style, have enabled them to vie with the glories of Brussels, Louvain or Ypres.

How remarkable that John Maxwell's Paris Town Hall was completed three years before Scott's publication!

There is a tradition of medieval Gothic guildhalls in England as at St Mary's Guildhall, Coventry, 1340-42 and enlarged 1394-1414. The original masonry of the hall of the London Guildhall is the work of John Croxton, circa 1411- circa 1440, which formerly had an elaborate wooden roof over the hall as in Paris Town Hall.

The Gothic tradition continued in the 1788 south façade of the London Guildhall by George Dance the Younger, albeit spiced with some Indian references. Then of the Bristol Guildhall, 1844, the pioneering historian of Victorian architecture, Harry Goodhart-Rendell, remarked:

although far clumsier in detail and arrangement, [it] resembles essentially the Houses of Parliament in the manner of its compromise between Gothic and Classic. This is the earliest neo-Gothic town hall of which I have found any record, and, if any others were built before the 'sixties of the century they were inconspicuous and uninfluential. I should be very much surprised to learn of any in whose design Pugin's True Principles had been regarded, although in matters of detail they might mimic his practice.

Aside from guildhalls, the large rectangular hall with an elaborate open-timber roof finds a great pedigree in English medieval halls. Most famous is the Great Hall of Westminster Palace, constructed for Richard II between 1394 and 1402, and another fine example is in Edward IV's Great Hall at Eltham Palace of the 1470s.

The great height of the tower Paris Town Hall is a monumental beacon of government just as in the London Houses of Parliament. It provides greater height than any classicizing dome or puny tower like St Catharine's Town Hall. Monumental towers are not part of an English medieval guildhall tradition; there is one centrally placed above the façade at Bristol (1844) but it rises only one storey above the walls of the hall.

The height of the Paris Town Hall tower is more likely to reflect Italian Gothic architecture. The famous English Victorian art and architecture critic, John Ruskin (1819-1900), eulogized on Giotto's campanile of Florence Cathedral and was enamoured with the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence of which the tower is of mighty height.

Be that as it may, other than the clasping octagonal buttress on the campanile of Florence Cathedral, the details of the Paris Town Hall tower do not depend on Italian exemplars, yet the inclusion of such a monumental tower may well owe something to Ruskin's love of this feature. The connection is difficult to prove but at least we may associate Maxwell's use of Gothic with Ruskin's view of the Nature of Gothic for the architecture of Northern nations.

Ruskin proposed that "Gothic is not only the best, but the only rational architecture, as being that which can fit itself most easily to all services, vulgar or noble". Following Pugin True Principles (1841), albeit without credit, Ruskin explained, "there is in cold countries exposed to rain and snow, only one advisable form for the roof-mask, and that is the gable, for this alone will throw off both rain and snow from all parts of its surface as speedily as possible. Snow can lodge on the top of a dome, not on the ridge of a gable."

It would be hard to imagine anything more appropriate for the climate of Upper Canada. Moreover, Ruskin's pointed-arch-and-gable definition of Gothic fulfilled with the roof of the Paris Town Hall.

Fig. 11. Paris Town Hall, exterior from N.

Fig. 12. Paris Town Hall, exterior, W doorway, detail.

Fig. 13. Oxford, Merton College, doorway , after John Henry Parker.

Fig. 14. Paris Town Hall, Assembly Room roof.

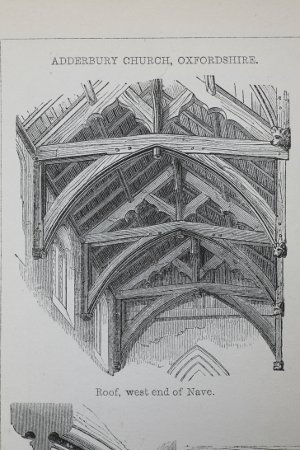

Fig. 15. Adderbury (Oxfordshire), St Mary, nave roof, after Bloxam.

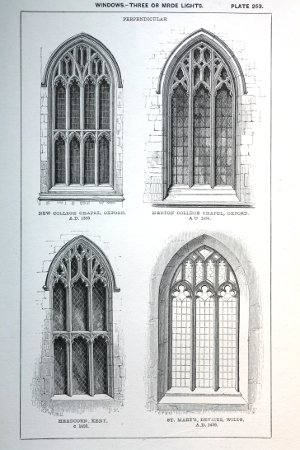

Fig. 16. Devizes (Wiltshire), St Mary, and other Perpendicular windows, after Parker.

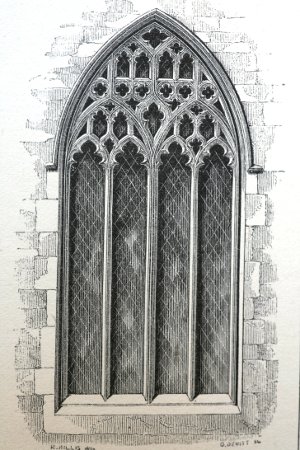

Fig. 17. Paris Town Hall, W window.

Fig. 18. Norwich Cathedral, presbytery window, after John Henry Parker.

On matters of detail, the octagonal clasping buttresses at the angles of the wings and the tower of Paris Town Hall find parallel on the tower of the London Houses of Parliament and on countless English Perpendicular church towers. The octagonal plan is also used for the angle turrets of the gatehouse of St James's Palace, London, built between 1532 and 1540 for King Henry VIII, which building also provides a source for the brick masonry and square-headed windows of the Paris Town Hall (Fig. 11).

Many of the details of the Paris Town Hall can be traced to English medieval sources published in the architectural press from the late 1820s through the early 1850s. The rectangular moulded frame for the doorway derives from Perpendicular and Tudor Gothic precedent and may be paralleled with the north doorway to Merton College Chapel, Oxford, illustrated in John Henry Parker's, Glossary of Architecture, and his Introduction to the Study of Gothic Architecture, in which there are also trefoil cusps in the spandrels (Figs 12 and 13).

The roof design with the combination of braces to form a pointed arch beneath a tie beam with a king post, principal rafters and diagonal struts with tracery on the principal rafters and struts is closely allied to the nave roof of St Mary's church, Adderbury (Oxfordshire), illustrated in Matthew Holbeche Bloxam's Principles of Gothic Ecclesiastical Architecture (Figs 14 and 15).

The three-light Perpendicular windows of the north and south fronts are a simplified version of one in St Mary's, Devizes, Wiltshire, illustrated in Parker's Glossary (Figs 11 and 16). For the east and west windows of the assembly hall Parker's Glossary does not provide a precise model but the fusion of the dagger with the mullions and super-mullions may be seen as a combination of the Devizes window with a clerestory window from the presbytery of Norwich Cathedral (Figs.16-18).

Comparison with George Gilbert Scott's civic Gothic of the late 1850s and 1860s, based as it was on the great medieval town halls of Belgium, may suggest that Maxwell was old fashioned in the use of Tudor Gothic for the Paris Town Hall. Be that as it may, it should be emphasized that Scott's row of eight terraced houses in the Broad Sanctuary, next to Westminster Abbey, illustrated in the English weekly architectural publication, The Builder, 1854, 115, has both pointed and square-headed windows and stepped buttresses as in Paris Town Hall.

Moreover, the articulation of the central pavilion of Broad Sanctuary with octagonal turrets capped with crenellations is similar to the facades of the north and south wings of the Paris Town Hall. Thus, at the very time Maxwell designed the Paris Town Hall, so Scott used the very same Tudor Gothic motifs in his Broad Sanctuary design.

Paris Town Hall was constructed at a time of outstanding growth and ambition in the community. The Great Western Railway Station in Paris opened on 15 December 1853. On 4 March 1854 the Brantford to Paris section of the Buffalo, Brantford and Goderich Railway was opened and the following month the two railway lines connected at Paris Junction. The grand scale and soaring tower of the Town Hall trumpet the ambitious civic pride of Paris in the 1850s.

Paris Town Hall is now for sale with a listing price of $895,000. For the past 20 years, the owner, John Runnquist, has maintained the fabric assiduously and he is keen to see the building preserved. The preservation cause has been championed by Paris actress and theatrical producer, Deano Wilson Rouse, who would like the building to become an arts centre.

The magnificent second-floor assembly room would be an ideal performance space, while the ground floor and basement could provide an excellent location for the Paris Museum and Archives.

Be that as it may, a recent article in the National Post reported, "Brant Mayor Ron Eddy said taxes would have to be raised to purchase the building and restore it, an unwelcome decision for residents living in a town where much of the economy has moved to the larger neighbouring community of Brantford."Mayor Eddy was then quoted: "The solution is to get several citizens together and form a foundation to fundraise."' The article continued: "Aileen Carroll, Minister of Culture for the government of Ontario, says that's a good plan - because the province is not interested in getting involved... She said the provincial and federal government(sic) do not have money sitting in a capital fund waiting to be designated for certain heritage priorities."

Will Mayor Eddy's "solution" work or will there be a buyer who is prepared to restore Paris Town Hall to its former glory? Should the fate of this internationally significant building be left in the balance, or should all levels of government be pro-active in saving this jewel of our architectural heritage?

Perhaps it is time to emulate the achievements of English Heritage, the government-funded organization that has proudly preserved thousands of buildings in England, and has successfully promoted public interest in the built environment with concomitant benefits for tourism and the economy.

By frank (registered) | Posted July 28, 2009 at 08:29:23

That is definitely a fantastic building! I don't believe that all levels of government should pool money to save a structure however I do believe that a committee can quite possibly raise the money to both purchase the structure and restore or maintain it as necessary.

By (anonymous) | Posted July 29, 2009 at 02:32:13

spam comment deleted by editor

By HotHungarianChef in Paris (anonymous) | Posted July 30, 2009 at 09:58:20

Culture more important than sport!

In a recent report,Tue, 21 Jul 2009- National News Survey reported that "Culture is increasingly contributing to New Zealand's economy."It also showed culture topped both sport and the economy in importance to their sense of national identity.

People believed culture was more important to our sense of national identity than either sport or the economy. Seventy-five percent of those surveyed thought culture and cultural activities were very, extremely or critically important to our sense of national identity. Landscape and environment scored most highly.

"But perhaps more important is the contribution of the cultural sector to the economy,"

"The arts and cultural sector is a significant part of the workforce."

The overall percentage of people employed in cultural occupations has increased significantly over the last few years.

"Evidence that employment in the cultural sector is growing is especially heartening as it dispels age old myths that pursuing study or work in the arts is a fruitless task.

"The arts and cultural sector provides work not only for artists, curators, designers, screenwriters and musicians but also for builders, accountants, printers and many more,"

"The sector also provides real economic benefits to the economy in terms of the income and value added to the economy. The cultural indicators suggest that cultural and creative industries have grown at least at pace with the rest of the economy."

I couldn't have said it better myself. All true statements whereever you may live.

So - why do we think that spending $22 million on an arena is fitting to promote sports in this depressed economy rather than preserve a Gothic Structure that would bring in money and preserve and promote the arts and culture be even a question in our minds?

But, the real question begs to be asked?

Why can't WE the People of Brant County - specifically PARIS, ONTARIO, CANADA - one of the prettiest towns anywhere, with the full support of our Province and Country, step up to the plate and "Sing the Praises of the Arts" and preserve our heritage and culture?

By jason (registered) | Posted July 30, 2009 at 10:19:35

I'd like to see both - government INVESTMENT local fundraising. HotHungarianChef has a good point. Buildings like this are absolutely an investment and help the local economy. Does anyone really think that Montreal or Boston would be as successful in their urban cores had they demolished most of it like we have in Hamilton?? Governments in the 50's-80's in Hamilton would have been wise to invest money to preserve our downtown. Our economy would be infinitely better for it today. Instead, the media, business and government has trained the public that money used for historic restorations is a "waste of time subsidy", yet money spent to demolish those same buildings and build a monster, mega-project is a worthwhile investment.

We demolish buildings like St Deny's and Eaton's and then build new buildings in some pseudo-historic style trying to emulate what was previously there.

Either way, tax dollars are being spent. Let's start spending them wisely.

By SteveP (anonymous) | Posted November 03, 2015 at 15:57:15

Its been purchased by the county! --> brantfordexpositor . ca/2015/10/27/live-blog-brant-county-council-meeting

Some fantastic times ahead...

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?