The setting of the Hamilton Sanatorium satisfies the early 20th century medical belief that high altitude and positioning on a slope contribute to the best conditions for consumptive patients.

By Mark Fenton

Published April 20, 2013

Das Kreuz von Lothringen ging im Jahr 1953. Es ist in einem melancholisch schön, steigt hoch in die Luft, seine robuste heraldischen Doppel Bars noch gleich die symbolische Gewicht, das sie tragen, aber verrostet, verdeckt durch Laub und die Neon in seinen Adern getrocknet. Es ist wie eine große Glocke stolz, aber ohne Zunge, seine Totenglocke klingen.

—Jeff Mahoney, thespec.com, Feb 01 2012 (from the English via Google Translate)

My daughter Emma and I rolled in front of the Hamilton Sanatorium late one night when I was teaching her to drive. To keep things interesting I'd been impulsively suggesting random turns down unknown streets.

An abandoned building on an abandoned road. Graffitied. Looming. Inhabited, we sensed, by ghosts. It creeped us out. We hardly dared to glance in the rear-view mirror as we sped home.

Inside, we locked the door, turned on all the lights, and made ourselves cocoa. A tacit silence around a place whose curse might be resurrected by even referring to it.

Next morning, the sun arose more brilliantly than we'd remembered it could. It was the single bright day we had this past February. We laughed at our fears from the night before (or at least Emma did).

She wanted more driving practice and urged that we return to the site, rather the way a parent urges a frightened toddler to inspect, under sanitizing midday light, last night's closet of ghouls.

With some reluctance, I agreed to drive back up with her. In the meantime, I had identified the building as the Hamilton Sanatorium, and had googled Jeff Mahoney's well-researched and moving article on its history, an article so concise and heartfelt I won't diminish it by paraphrasing. You can read it here.

We parked. Steps away from the car my foot fell on something which gave a small crunch; subtle yet alarming, like the murmurs you don't want your doctor to hear as you breathe in and out through your mouth.

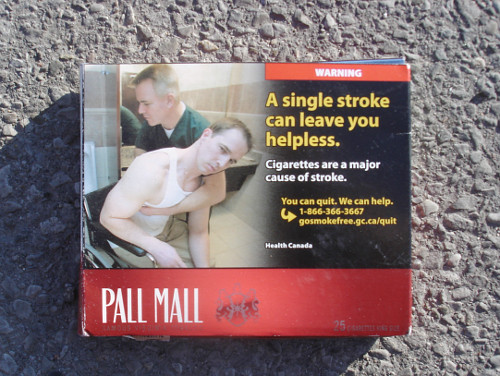

As a non-smoker, I'm an outsider to the image-world of cigarette cartons. Retailers hide them ever farther from public view. The pictures of oral cancers and pregnant women communicate an obvious message. This one, however, baffled me. I picked it up.

The one thing to be said for my unsanctioned photo journeys is that in desperate efforts to find a story, I pick an awful lot of stuff up off the ground. When I'm done with each item, I put it in the appropriate recycling container.

This is an incidental and uncompensated service to the community, and one which I hope police departments and security offices will add to their files on me.

I'm not accustomed to reading the accompanying texts because I expect images on these warnings to be self-contained enough to communicate something relating to the dangers of cigarette smoke. But all I can think when I see the above picture is that it's a caution against having unprotected sex with a stranger in a lavatory.

From a public health perspective this is a useful reminder to all of us, but how really does it target the risks of smoking?

Maybe, I think, there's an agreement between Health Canada and the smoker. Smokers make a choice that costs the taxpayer more money than the equivalent non-smoker costs the taxpayer.

Perhaps, to compensate for this, cigarette users have been made ambassadors of risk behaviour in general. Perhaps drunk driving, unsafe water sports, and reckless use of power tools adorn other packages.

'What cautionary script am I expected communicate to passers by next time I go outside and light up?' the smoker asks herself as she buys a new pack. (Do smokers ask to shuffle through the packs and choose the most easily communicated narrative? Like those people at convenience stores who dither for a small eternity over the choice of lottery ticket as I stand behind them with a bag of milk just wanting to get to bed.)

But no. The image is simply intended to illustrate the increased risk of stroke from smoking. I stuff it in a pocket to examine more fully later on.

The first thing you notice about the Hamilton Sanatorium, in daylight, is that it's perched close to the mountain brow, giving a dramatic view of the lower city.

This suggests an immediate similarity to The Magic Mountain, Thomas Mann's masterpiece of literary modernism set in a Swiss sanatorium on a rugged slope in the Alps.

The setting of the Hamilton Sanatorium is hardly this dramatic but it does satisfy the early 20th century medical belief that high altitude and positioning on a slope contribute to the best conditions for consumptive patients. Dryness plus downward airflow to sweep the disease away and into eternity.

If you haven't read The Magic Mountain, here's what happens. It's 1907. A young engineer named Hans Castorp goes up into the Alps to visit his cousin Joachim at the Berghof Schatzalp Sanatorium in Davos Switzerland.

Berghotel Sanatorium Schatzalp (from Wikipedia)

Less than two days after his arrival, Hans begins coughing up blood. Hans meets with a team of physicians and gets diagnosed with the disease and as a result is embraced as a peer. (When Hans was thought to be a mere visitor in robust health he was given the consistently Alpine-cold shoulder by patients and doctors alike.

In this book, pathology is normal and health is suspicious. The medical opinions of physicians suffering from TB are more respected than those of the healthy ones. I know. It's messed up.)

So. Hans gleefully relinquishes his youthful ambitions and settles into the culture of illness, with its daily naps and endless medical exams. It's not so bad a life. A nice view and reasonable food (food which everyone gripes about; pretty much like every dorm-cafeteria situation in the world.)

Hans engages in spirited conversations and long intellectual debates with representatives of the diverse cultures and political ideologies of pre-war Europe. You can see what Mann is doing here. The cultures and ideologies of a dying 19th C Europe, all assembled in a lofty retreat in Switzerland (the tradition neutral zone). Right before World War I. European civilization on the brink of committing suicide.

You probably guessed that the Berghof is not a place of universal socialized health care. The bill comes once a week and it's a hefty one. This is care for the over-privileged. The elect who've passed miraculously though the eye of a needle into a realm very close to the kingdom of the gods.

Some of the patients are cured (not always the ones you'd expect). Some die (not always the one's you expect). The complex relationship between a sound mind and a sound body is exhaustively explored. Mann described the book as a satire about the health care profession, implying a certain level of comic exaggeration.

Fair enough, but as a 700-page book that subverts some of the loftiest ideals and institutions of Western civilization it may be the world's longest comedy with no l.o.l. moments whatsoever.

I hadn't read TMM since I was an unemployed post grad suffering from a respiratory infection I couldn't seem to shake. And I'd sold my old copy along with easy to replace books like Plato's Republic and The House at Pooh Corner, and dozens of similar titles, thereby opening up a wack of shelf real-estate. But this meant I lacked a copy of TMM to brush up on.

I checked the HPL and found there was a copy waiting for me - what better item, really, for my municipal tax dollar to go towards? - at the Mount Hope Branch, a mere 20 minute walk from where I work. I liked that the branch was not only on the mountain but had 'Mount' in its name.

I went there.

A cold bright April 3. The ditch was full of litter as ditches are when snow melts.

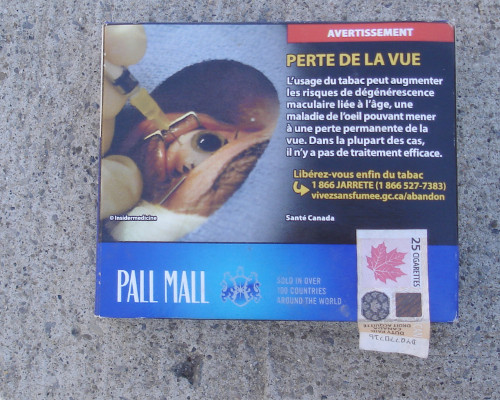

When cigarettes have vanished from civilization for good, what tales will be constructed around these images, should a future society find my catalogue?

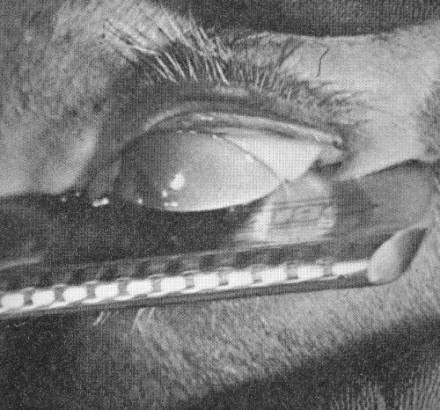

This one was my favourite.

From a distance it looked like the eye of some animal with leathery skin, perhaps even with fur surrounding it. On closer inspection it is a gruesome picture of a human eye forced opened with shiny tools penetrated by a syringe.

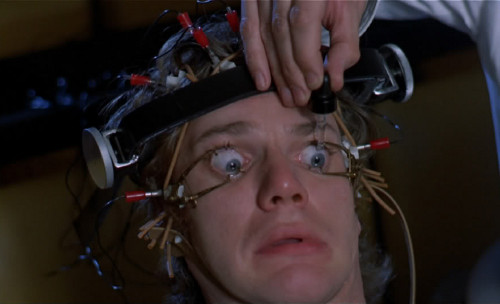

This, I think, goes one better than the Ludovico treatment in A Clockwork Orange, where Alex is injected with a serum to make him nauseous and then has his eyes forced open to regard films of violent acts for which he has a predilection. A Pavlovian transformation of pleasure into aversion.

From the point of view of cinematic terror imagine if the needle had gone straight into the eye! It would elicit that kneejerk squirm like the one we experience during the iconic shot from Bunuel's Un Chien Andalou.

I also see it as an inversion of Matthew 19:24. Could one not say: It is easier for a needle to enter the eye of a camel than for a god to enter the kingdom of a wealthy man?

I reached the Mount Hope library and quickly found my copy of TMM. It was 14:15 on a Wednesday. There were no other browsers when I went in, giving the place a two to one ratio of librarians to visitors. I felt watched. I could tell they were struck by how quickly I found my book and made my way to the checkout.

The librarian asked my address in order to verify it in the system, something I don't recall ever happening at a library checkout. I can only assume she was making a note in case she was questioned by authorities. As I muttered words to the effect that, yes, I had been at that address for years, my life was quite rooted and stable thank you, half a dozen soiled cigarette packs tumbled out of my jacket pocket, and there just wasn't going to be any way to explain that in ≤ 50 words.

This time through TMM, I was struck by the book's attitude to smoking (something that, in the 21st century, the average 10-year-old would judge as a probable influence on respiratory health). The first thing we learn about Hans's luggage is that he's smuggled 200 Maria Mancinis into Switzerland and that "getting them through customs had been as easy as pie." (John E. Woods, translation, Alfred A. Knopff 1995).

He's referring to a brand of cigar. It's the 1907 equivalent of getting 200 Montecristos into Miami on a boat from Havana.

Presumably Hans imagines that the second-hand smoke of 200 cigars is just what a TB sanatorium needs. In a passage way too long to reproduce, he rhapsodizes on the joy of smoking. Occasionally in the novel a Doctor will condemn smoking, but his argument is usually that it contributes to a state of melancholia in patients.

If I could move my photos as easily through time as I can move them through space these gruesome images of tobacco aficionados might educate a pre-WW I Swiss doctor or two on the respiratory perils of tobacco.

There is a general feeling that memorials should contain illumination.

In Hamilton the age of neon saw the erection of the Cross of Lorraine, which though it now stands dormant, is still a powerful memorial.

I know it was operational as late as the 1990s because when I first moved to Hamilton I could see it from my apartment on Aberdeen glowing so brightly it kept me awake through my curtainless windows.

Even today its form, like Macbeth's dagger, will appear suddenly before me and without context. I used to think it was a stigmata manifestation. Now I'm fairly sure the Cross of Lorraine just got burned onto my retina.

Before I picked up my library copy of TMM, I spoke with my friend Lelde, as I'd seen a copy of TMM at her house and wanted to confirm the location of the sanatorium, since I hadn't read the book in decades. Lelde, who has been basically everywhere, not only knew the Sanatorium was in Davos Switzerland, but had actually been there and had photos!

It's been turned into a hotel, something Hamilton should probably think of doing with its. Here's a view through the dining room window.

photo, Lelde Muehlenbachs

Gerhard Richter, Drei Kerzen 1982

A pretty chilling metaphor for the treadmill of critical disease. As Hans Castorp discovered, the way in is easy but the loop of disease is virtually inextricable. It's not hard to see how a three week stay can turn into seven years.

I don't usually praise my own photos but I like how the above picture turned out. I take no credit for its composition. It was a one-chance-to-get-it-right drive-by shooting (from a motoring perspective only safe because Emma was at the wheel.)

Isn't it, though, almost De Stijl with its primaries in a clearly defined geometry of triangles and octagons and rectangles? I call it Accidental Winter Collage and if you want a high definition copy to frame for a loved one just hit my e-mail and we'll work something out.

One of the odder things about this very abandoned location is the fact that it has an active bus stop. The bus route equivalent of a NYC phone booth in the 70s. (Doors ripped off. Remains of smashed Plexiglas spray-bombed from top to bottom. Chain-ganged phonebook burnt to its gutter. But when you went in and picked the phone you miraculously got a dial tone.)

Same deal here. You can take a bus right to the Sanatorium, light your candle, sit for a while, and then catch a bus back home. No other vehicle passed during my visit, but I counted a total of four buses in the 20 minutes I was there,

two from each direction.

And they actually stopped. No one got on. No one got off. As well as being a hazard to a guy standing in the road and taking pictures, they felt slightly eerie. Like ghosts being returned to the place whence they departed this world.

This bus crossing is as good a place as any to note that one day shortly after I'd started this essay Jeff Mahoney and I approached each other from opposite directions, stopped, conversed, then continued our independent journeys.

I mentioned that I wanted to showcase the Hamilton Sanatorium alongside the Sanatorium of TMM, and could I use a quote from his article as an epigram, to which he replied. "Absolutely, but only if my quote can appear in German."

Since I have not read or written the language since a year of German as an undergraduate, I gave the job to Google Translate. If you are a German speaker, feel free to suggest corrections. If you are not, here's Jeff Mahoney's untranslated text.

The Cross of Lorraine went up in 1953. It's beautiful in a melancholy way, rising high into the air, its sturdy heraldic double bars still equal to the symbolic weight they carry, but rusted, obscured by foliage and the neon dried in its veins. It's like a great proud bell but with no tongue to sound its knell.

This quote can, I think, serve as the end of the Jeff Mahoney interlude and the place where I get back to showing some more of Lelde's ass-kicking photos of The Berghotel.

photo, Lelde Muehlenbachs

If Lelde's image of the dining room lacks anything, it's the filter of second hand smoke we know it would have been suffused with.

photo, Lelde Muehlenbachs

I understand from Lelde that the x-ray room of the novel is now an x-ray bar (above). In the novel patients are always walking around with their x-rays and showing them to other patients. Sort of a "my lungs are worse than your lungs" competition.

But what exactly is an x-ray bar? All I could think of is a club where young people go and x-ray their friends. I'll bet there are special drinks with a substance that shows up on the x-ray and you can x-ray people drinking it and see it going into their stomachs.

And then you can probably get cool shots of skeletons grinding on the dance floor and later people discover that their so-called friends have put these skeleton pictures up on Facebook and this ruins relationships (seeing your beloved and a rival together without clothes is agony; seeing your beloved and a rival together without skin...?) and horrifies their parents who lament the decadence of today's youth who don't have real afflictions like TB so they manufacture cruelty with self-indulgent nonsense like this and are we as humans just programmed to visit deliberate cruelty on one another?

Where the façade of the Hamilton Sanatorium is imposing, the rear approach is intimate, an almost random accumulation of cubes as though the building were conceived by a toddler playing with blocks.

Poignant when we think of the number of children the sanatorium ministered to.

Canada's Digital Collections, Industry Canada

Perhaps the most arresting accidental feature of the building's decay is this broken fire-escape.

A ruined escape route seems is at least as alarming as a crossroads named Sanatorium and Sanatorium. Yet again suggesting the prospect of a three week holiday stretching to seven years of treatment.

On the other hand, what could be a more victorious monument to disease than the decaying facility once used to treat it? If all disease could be defeated we'd surely tolerate the abandoned buildings and dried neon littered around us.

I finished The Magic Mountain and felt I should tie up the essay I'd been working on as I was reading it. When the novel ends it's 1914. Hans Castorp is released with a clean bill of health. He enlists as a foot soldier. The last paragraphs describe him advancing against the enemy machine guns. We don't learn his fate but we don't fancy his chances.

The long endgame of cigarette smoking felt like a good endpoint for my essay. I decided to go outside and photograph the first littered cigarette pack I found. Not much of a challenge. On a scavenger hunt it would be the one checkmark everyone gets. Like the first question on an IQ test, the one that's so easy it's just there to prove the subject is a person and not an empty chair.

Try it for yourself. Reading a random cigarette pack is the post-industrial equivalent of throwing the I Ching and when you're done, you can recycle it and the world will be just a little bit tidier.

I cheated. (Why not? When I don't like my first I Ching hexagram I just throw the coins again.) The first one I found exhibited an extreme oral pathology whose mottled surface summoned up an image of the Swiss Alps. But that connection fell below my personal standards of good taste.

It was also far too terminal for my liking. One of the continual revelations of TMM is that who survives and who doesn't is a larger reality than the medical establishment can explain or even than the disease itself can command.

The second package I found portrayed a mother and daughter whom we are told are both addicted to nicotine.

I liked the family solidarity. I also liked that I'm not told what their prognosis is. Either or both might quit smoking. Either or both might repair the damage through radical changes in lifestyle. Either or both could continue to smoke and just get lucky and live a long, relatively healthy life anyway.

It's an indeterminacy that acknowledges the limits of caring or treatment. And it supports Mann's own description of the book, as one that explores "the idea of the human being, the conception of a future humanity that has passed through and survived the profoundest knowledge of disease and death."

By abert (anonymous) | Posted April 20, 2013 at 14:10:16

"all I can think when I see the above picture is that it's a caution against having unprotected sex with a stranger in a lavatory."

huh?

By Glades (anonymous) | Posted April 22, 2013 at 19:46:14

Another beautiful, surreal essay by my favorite RTH author. I can only guess there aren't more comments because it's not an article you can argue with so much as just experience.

By Selway (registered) | Posted April 24, 2013 at 03:19:06

Yup, another beauty.

"But what exactly is an x-ray bar? All I could think of is a club where young people go and x-ray their friends. I'll bet there are special drinks with a substance that shows up on the x-ray and you can x-ray people drinking it and see it going into their stomachs."

Actually, it's a place where depraved youth go to listen to collages: music pressed on discarded X-ray film.

By Babyf150 (anonymous) | Posted May 02, 2013 at 16:52:13

Banal is the only word that sums up this article. 20 minutes of my life wasted.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?