If you like movies about how movies are made, you'll love this story about how a story was made.

By Mark Fenton

Published March 19, 2007

Sure, you've watched way too many of those 'special features' that fill up the seemingly limitless space on a Hollywood DVD. You know the ones, where the actors talk about what a great guy the director is and the director talks about what great guys the actors are and you sit in your living room on a Saturday night thinking how great it must be to work in the motion picture industry and wonder why you're, say, stuck in a minimum wage job at Wal-Mart with small-minded embittered co-workers who obviously eat too many transfats, when you obviously could be making better movies yourself, or at the very least, be making better "making of" movies.

But there are those "making of" films I wouldn't want to give up. Like Vivian Kubrick's charming and intimate film of her Dad making The Shining (Stanley, not, I'd say, an artist one turns to for charm and intimacy.) My favourite scene is the really tense conversation between Kubrick and Shelly Duvall. And I love how Shelly refuses to put down the knife prop, which she must have been holding day in and day out while shooting the closing scenes of the film.

(By the way, that dark triangle in the lower left is Stanley's right arm and upper body, in a parka, which I'll admit is lame, but it's the best I could get off my TV with a digital camera, and further evidence, if you needed it, that Stanley Kubrick is great with a camera, and I'm not). He's not happy with what Shelly Duvall is giving him and she's really not happy with him. Trust me on this. Rent the DVD just for the special feature.)

You can tell from Stanley's tone of voice that the knife in the hand is really having an effect on him. I'm going to try just casually holding a big knife like that, the next time I have to get my driver's licence or my passport renewed, and just see if it makes things go faster. Oh, I know what you're thinking. If anyone looks at me like they're wondering whether they should call the Finest I'll just say I'm an actor preparing for a role. But I think the knife will get people taking me seriously.

But let's look at other arts. How about Hans Namuth's film of Jackson Pollock painting No. 29 1950 on glass?

Frame Sequence by Hans Namuth; Reproduced from Pollock Painting, Agrinde Publications Ltd. New York, 1980

Whenever I even see a photograph of it I want to rush down to the National gallery of Canada and see it again, and marvel at the apparent ease and awesome control he has with a stick and paint and a bunch of bits of industrial detritus. The film suggests his ablities; the painting proves them.

I must say, I worry a bit that the colour of those little bits of industrial plastic - never intended for fine arts use - might already have faded. The ephemeral quality of its materials are part of its power. making me desperate to absorb the effects of the pigments before they're gone. Even the very fragility of the piece - it's on glass after all - is part of its high strung presence.

It's similar to the way I'm both terrified and thrilled when people lean their treasured porcelain plates on a shallow ledge high on the wall, a few centimeters from the edge. As though the very act of viewing them could cause them to fall to their annihilation, and so I give them only the most brief and furtive of glances, having to complete a sense of their design in my own mind. I'll admit this may not be a universal anxiety, but rather my own neurotic baggage around things I broke and got punished for in early childhood. No conscious memory of that. Just a theory.

My favourite description the public's fascination with how artists manufacture their stuff is a song by The Fall, called 'How I Wrote Elastic Man.'

The Fall, 1981 Doornroosje, Nijmegen, The Netherlands (Source: Visi)

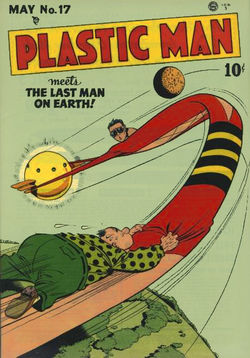

I can only assume this song refers to Jack Cole, creator of Plastic Man -

Plastic Man #17 (May 1949) Cover art by Jack Cole.

- particularly since Mark E. Smith, who typically sings like a man missing parts of his tongue, sounds more like he's singing "How I wrote Plastic Man" during the refrain. Incidentally, all my information on Plastic Man was supplied by my friend Steve Bernhardson, a man with more information about Plastic Man at his fingertips than any sane man should. He tells me Jack Cole committed suicide, an act I hope wasn't a response to being relentlessly questioned as to his work method.

I'm too tired,

I'll do it tomorrow

The fridge is sparse

But in the town

They'll stop me in the shops

Verily they'll track me down

Touch my shoulder and ignore my dumb mission

And sick red-faced smile

And they will ask me

And they will ask me

How I wrote elastic man (x20)

Forgive me if I don't write out the refrain the full twenty times that Mark E. Smith repeats it. I have never been part of any such class, but I understand that courses for studying the music and lyrics of rock songs are now offered for credit in universities. In this case a professor would probably need to hand the students the full set of lyrics, complete with the repeated lines typed in full. A cryptic text in this case. Perhaps better suited to a intellectual rigor of a graduate class.

Dr. Winks: Any theories as to why Mr. Smith repeats "How I wrote Elastic Man" not 19, not 21, but exactly 20 times?

Student 1: Twenty digits on the human body. For reasons too involved to go into here Mathematicians have suggested it as a more compelling and malleable base for a numeric system than 10. Perhaps a base Plastic Man operates with. Perhaps the secret to his powers.

Student 2: The Twenty Year Curse. [A.K.A. the Zero Factor.] (hand gestures for brackets) All American Presidents elected in a year ending in a zero, consecutive from 1840 to 1960, died in office. Sometimes violently. The sense of national menace, so key to the superhero mythos, is implied.

Student 3: I fear that, yet again, I'm the one destined to crank it all down a notch. Well, (shrugs) so be it. For me it's as simple as the familiar parlor game "Twenty questions." "How I wrote Elastic Man." The line neither questions NOR answers. Rather a statement of relationship between Interrogator and Interrogated. The still point in the power dynamic. Potent in possibility. Everything hangs in the balance.

Dr. Winks: Mmmmm. Insightful. Now, lets discuss the semiotics of the [Plas/Elas]-tic (hand-gestures for brackets) Man construction.

It was this progression of thoughts, concluding with me actually humming the How I Wrote Elastic Man refrain – yes, my thoughts do progress in such a manner, particularly when I'm supposed to be at work, earning my pay - that lead me to try and come up with a comprehensive list of works about making a work of art.

I thought of Thomas Mann's "The Genesis of Dr. Faustus", which I've never read, but which is supposed to be a surprisingly riveting account of writing a novel. When it comes to poetry there is, of course, the really famous account - in his own words - of Coleridge writing Kubla Khan during a drug hallucination, only to be interrupted by someone known to literary history only as the "person from Porlock" whose knock on the door supposedly prevented it from becoming the epic it might have been.

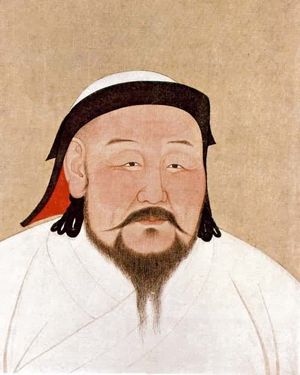

Kublai Khan (Source: Wikipedia)

I think it's fascinating to live a life only to be remembered as someone who inadvertently wrecked a famous work of art. Although my suspicion, given that Coleridge had a pretty small success rate as a poet, is that the Person from Porlock actually made Kubla Khan the great thing it was by cutting it off when just as Coleridge was about to sail off into a tedious lavender mist of Romantic self-indulgence.

As Coleridge tells it: "with the exception of some eight or ten scattered lines and images, all the rest had passed away like the images on the surface of a stream into which a stone has been cast, but, alas! without the after restoration of the latter!"

Not to compare myself to a poetic genius, but as I've been working on this humble article, my Blackberry must have rung at least six times, and when that happens I just put down what I'm doing and then go back to the article when the interruption is over and I don't make a big deal about it! Under the circumstances I find it hard to imagine a knock on the door getting the attention of Mr. Coleridge. What kind of overdetermined type-A personality thinks he's so good at multitasking that he can answer the door and write a great poem while he's messed up on hard drugs?

Then it occurred to me that I couldn't think of anyone who had written about how he or she wrote a short story. And since no one has ever expressed interest in how I create my texts, I am happy to speak of the process, without becoming suicidally depressed.

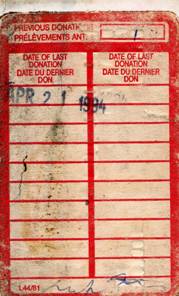

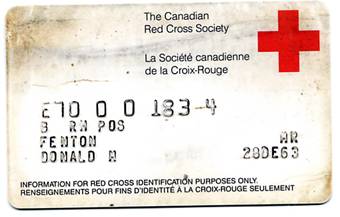

On Thursday April 21 1994 when I was employed as a Legal and Consumer Counsellor for Hamilton's CAA office (long story, not worth it) I walked out on my lunch hour and gave blood at the Canadian Blood Services Office, at 299 Main Street East.

I am embarrassed to say that I have not given blood since then. I don't know if it's still part of the process, but at the time they handed me a questionnaire asking a series of lifestyle questions whose answers could identify the donor as being high risk for infections you just don't want to get from someone else's blood.

As is often the case with such questions, couched as they are in the most clinical of language where the colloquial equivalents are so obvious, I found the questions terribly funny and shared my thoughts on their peculiar content with the clerk who'd handed the questionnaire to me. She didn't find them funny at all, and I could tell I was making her uncomfortable, so I just shut up and went over to the cot and bled.

Some years later, probably in about 1998, it occurred to me to write a story about a marginal person (i.e. more marginal than myself) who chooses to give blood to improve his sense of self worth. I retained part of the conversation I'd had with the blood clerk and even given Fisk my own blood type.

That's it for the autobiographical elements. The rest (other than the Hamilton locations which I love) was all invention.

I liked the story but a few things didn't click so I put it away and forgot about it until Ryan McGreal mentioned to me that he was planning an issue of Raise The Hammer with a fiction section and that I might want to contribute something.

I am meticulous about backing up my hard drive by burning its contents onto CDs at regular intervals so I thought I'd be able to find it quickly somewhere in a stack of well organized CDs I keep in a cabinet above my desk. I went through all the ones with plausible dates. Not finding it easily, I became steadily more frantic.

I then ransacked the bottom drawer of my desk and found a folder of randomly collected early drafts of stories and it wasn't among them.

The final possibility was a the large set of bins on the third and chaotic floor of my workplace where I keep all kinds of stuff I'll probably never need, but which it would take too much time assessing for me to thin out.

There were several dozen CDs burned during the period in question, but I still had no luck. I was beginning to fear that I'd have to rewrite, from memory, a text I hadn't read for almost a decade.

I thought of the most famous story I knew of a lost manuscript.

On the night of March 6, 1835 John Stuart Mill knocked on the door of Thomas Carlyle and stood before Carlyle bearing the aspect of a condemned man.

The most familiar view of Carlyle is as the 'bearded sage' with a penetrating gaze. (Image Source: Wikipedia)

Carlyle had been working for years on a history of the French Revolution, with continued editorial support from John Stuart Mill, who was a close friend. Just before delivering it to his publisher Carlyle had given the manuscript of the first volume - some 500 pages - to Mill for a final reading. Mill's maid, confusing the stack of heavily worked, tattered pages for kindling, threw them on the fire where they were completely burnt. No system backup. No CD copy. No floppy. No photocopies. No carbons. The working draft was it; and it was gone.

J. S. Mill (Image Source: Wikipedia)

This is where the psychology becomes fascinating. On his arrival at the Carlyles' house Mill was so wracked with guilt and in such an extreme emotional state that Carlyle and his wife felt themselves forced - in fine Victorian fashion - to keep a stiff upper lip, suppress their own horror, and deal with Mill's delirious and dangerous feelings of remorse. It wasn't enough that Thomas and Jane Carlyle had just lost years of work, they now had to become John Stuart Mill's therapist acting as though reproducing the manuscript was the least of their concerns.

HOW I ALMOST DIDN'T WRITE THE FRENCH REVOLUTION: A Chamber Drama

Tom: Hey - could have happened to anyone. Don't beat yourself up about it. Have a Scotch. It's just a book after all.

(Jane Carlyle casually hands John a Scotch and soda, which she has stirred with a single relaxed flourish.)

John: I know, but you worked so long - (downs the drink in one gulp) Look - why don't we treat it just like an insurance claim. Calculate your time, and I'll pay for it out of my own pocket.

Tom: Wear looser shoes or something, man. You are uptight! You gotta learn to decompress and not take things so seriously. It's not like somebody died.

Jane: It's not even like someone lost an eye. (Hands John a second drink)

John: (Still stressed but by comparison to a few moments ago, showing signs of considerably relief) I just wish there was some way -

Tom: Hey, if it makes you feel better and you have some half-used paper lying in the recycling bin, I can always use it to re-write the thing. Now can we pulease move on?

John: I feel like such a dork.

Tom: Dude, let it go. I'm over it. (Looking over at Jane with a forced sense of fun) Hey! Why don't we all have a game of Foosball?

Jane: (slyly) Or maybe Twister!

Relieved of a terrible burden by these great friends who have just proven themselves still greater friends, John Stewart Mill stays for hours. It's only after he finally leaves that Thomas and Jane themselves are able break down and vent their anguish at what has happened.

Carlyle rewrote the book from memory. He claimed it to be better than the original. It made his reputation as one of the great minds of his generation. Though I've always wondered what John Stuart Mill's maid felt about the whole event. Was she really upset at what she'd done? Did it come up at her performance review? Did the Mills send her on a remedial Paper-with-handwriting-on-it Identification Workshop?

We'll never know. She probably wasn't the kind of person who read books about the French Revolution. As a working-class Victorian woman she's been - as the Marxist Feminists say - "written out of history."

I used to tell this story to friends who had just lost an essay in the computer shortly before a deadline, stressing the fact that often the second version - forcing the essentials to the surface of the prose: ineffably gaining from the experience of a dry run - makes the manuscript better.

Telling people this, however, has only ever made them angrier - probably finding my attempt at helping them misguided, when what they probably really want is for me to sit down and type for them as they dictate. Thinking about Mill and the Carlyles didn't make me feel any better either, as I rifled through CDs.

Thankfully I didn't have to go the route of rewriting from memory. I finally found a copy on a backup of what was labeled as work stuff. I don't think it would have been better if I'd retyped it. Certainly it would have been different. I was amazed at how little of it I remembered.

The advantage of leaving a manuscript so long is that after almost a decade most writers are very different than they were when they wrote their earlier draft. They are interested in different things and their vision of the world has usually changed to some extent. So it's very easy to approach an old story with detachment; as an editor of someone else's work.

I quickly read through 'Fisk', isolated the parts of the voice that didn't ring quite true, and repaired them. Beyond that I didn't change anything in the action or tone. It was a story by a person I wasn't anymore, and for better or for worse that's the only way it could be.

All that remained was too take a few photos, not because the story necessarily needed them, but because it's free to run colour photos in an on-line magazine - a phenomenon that still thrills me - and because it was the only nice day we'd had since mid-January and fresh air is always good for my mental health.

As I said, I was ashamed that I hadn't given blood since April 21st 1994 and this seemed like an excellent excuse to do so and maybe even get a picture of myself bleeding into a bag, to use in the story. So on Wednesday February 21st 2007 at about 12:30 pm, driving Westward on King Street East, I was struck by the most sublime ensemble of young people standing outside a Pizza place enjoying the warm weather.

I checked my rearview mirror. Nothing behind me. I slowed. My window needed to be rolled down, covered as it was in spray from the thaw. Also my camera was still in its case, and I had to fumble with that. Let's say I wasn't as smooth as I might have been in getting a candid photo. I still hoped it would be natural enough to be of some use to me.

It was the only photo I took that day in that immediate area. Driving on, I thought vaguely that I heard someone shouting at me, but told myself I was just imagining it. Three blocks up I pulled in and parked at Canadian Blood Services. They had friendly smiles for me, but they wouldn't take my blood. Sometime between April 21st 1994 and February 21st 2007 it had stopped being a donor clinic and become just administrative offices. If I wanted to get rid of some blood, I'd need to go up to the Meadowlands Power Centre.

Of course I love photographing the MPC, and sure, someone out there needs B RH Positive blood to stay alive, which is what giving blood is really about, not to supply me with photogenic subjects when I'm out on a frolic of my own. But for purely selfish reasons that wasn't where I needed to be today. Slightly disheartened I took a bunch more pictures moving further West on King Street, then up James Street.

and finally I found myself wandering the food court of Jackson square, some twenty feet below the Jackson Square Rooftop which provides the setting of two of my previous RTH photo essays, and where, who should I see, but the editor of RTH himself.

The sharp-eyed, ever-observant RTH editor

At the moment I snapped this photo - exactly 1:30 pm - Ryan still hasn't seen me, even though I'm only two feet from him. The high school students most definitely did see me, and they were 20 feet away. Interesting.

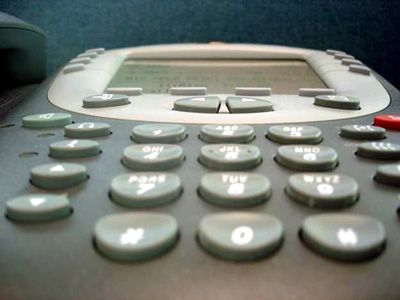

By 2:45 I was back in my office when the phone rang, displaying the words HAMILTON POLICE DEPARTMENT on the screen. Though I got it on the second ring, for some technical reason I can now only attribute to the initiating process of a wire-tap system, it hung up immediately. I'm often the only person in the building. No doubt the Finest had been interested in some activity around the building, and had probably already found an answer somewhere else.

I thought no more about it until late that night when my partner, Jennifer, said, "Oh, by the way, there was a very strange voice-mail message for you today. From a 'School Youth Officer' I think it was."

"Is Dad," asked one of my daughters, "going to go to jail?" (Her tone didn't sound so much worried for me, as excited at the prospect of having a Dad who's done time.)

I did what any normal documentary photographer would do. First I listened to the message, which was pleasant but somewhat contradictory in tone, insisting simultaneously that needed to call back, that there was nothing to worry about, but, once again, that the officer did need to talk to me. Implied I felt was that if I didn't return this call then he'd just come by with, you know, a gun and handcuffs and another officer, like they do in the TV shows. It was obviously too late to call back, so I had the night to think about it.

I then raced upstairs to go through my photographs and quickly zaprudered the one that I knew full well was the catalyst for all this.

In my clumsiness to get a "natural" composition, while making sure no one tail-ended me, the two youths in the fore-ground had seen everything (In one of the scenarios my imagination was already constructing, the call would include a warning from the Finest on the hazards of distracted driving.)

I could well imagine the sequence of events. Students collectively memorizing my licence plate. Rushing back to the school and hovering around the Principal's office, vibrant with purpose. The Principal returning from lunch with the remainder of a sandwich he couldn't finish in a Styrofoam container.

The students quickly relating my suspicious activity - even before they can all squeeze into his office - describing me as an old guy, someone who probably looked like the red-haired guy in the Archie comics when he was younger.

The Principal leafs through his file of Police advisories of sex offenders and violent criminals in the area, all of whose descriptions have some elements in common with me. He nods to the students, commends them on their quick thinking and fast civic action, grabs the paper with my plate number and hits the pre-programmed emergency number: "School Youth Division please - "

Of course, I told myself, if you were a police officer calling a person suspected to be a serial killer, you'd say there's nothing to worry about. Otherwise they not only wouldn't return the call, they'd catch the next plane for Brazil. Right?

As I lay in bed I contemplated all sorts of interrogation tactics and measured responses to them. While not a member of the bar, I don't consider myself a tyro in jurisprudence. I even watch the occasional Crime Scene Investigation on TV. They had better make sure they didn't underestimate this former Legal and Consumer Counsellor for CAA.

Oh, I would tell the truth and only the truth, but I would be a verbal Elastic Man, flexing carefully around any questioning technique designed to trick me into incriminating myself. And I certainly wasn't going to confess to anything when I called back and Officer M--- picked up the phone. I wouldn't say a word until I knew what the charges were.

What if, for instance, he wasn't calling about the photograph I'd taken, but was instead collecting on a warrant that had been outstanding since I myself was a School Youth? I couldn't think what this warrant would be for, but I must have done something illegal and foolish at some point in my youth. Doesn't everyone?

Before falling into a dreamless sleep I kept coming back to the only partial alibi I had. The fact that I had encountered Ryan less than half an hour after the photo I'd taken of the High School students. This had to be significant. I had even told Ryan I was out shooting photos for a Raise The Hammer article. He would bear witness.

He was, after all, the publisher of the magazine I was that very afternoon at work on. I had the photo to prove it! How much better could I do than that! Even though I hadn't had the time and date feature turned on, surely, like all digital machines, somewhere hidden in its innards was a record of the moment it was committed to memory…

When I called Officer M--- back the next day at exactly 8:35 am I was struck by how close the chain of events leading up to my being contacted by the police was how I'd imagined it would be. A group of students had seen me "taking photos of school property" [!?] (For the record I didn't take a single picture of any school property that day. I took a photo of people on the sidewalk in front of a Pizza place. But whatever...)

I should say that the officer in question couldn't have been more pleasant, and apologetic about having to follow up this lead as there was nothing that lead him to believe I was doing anything improper. But it was, obviously, his job to investigate these things.

I would describe this as, in all ways a positive and community building experience. I stated the purpose of Raise the Hammer my role in it, and even encouraged members of the police department, the Principal of the school, and the students to read Raise the Hammer and post comments. The last thing I wanted to do was make anyone uncomfortable. You could say I even managed to do a bit of PR for Raise the Hammer.

Finally I encouraged Officer M--- , should he have any remaining questions about my activities, to read my contributions which, I was sure, would dispel any doubts he might still have and might even prove diverting. Although, just now rereading how I've written about how I wrote 'Fisk,'

I wonder what made me think that reviewing my articles would convince anyone that this was the work of a man possessed of a healthy state of mind.

By billy (anonymous) | Posted March 20, 2007 at 21:28:36

a fair amount has been written about how Jack Karouack (spelling?) wrote: "On The Road"

By Fenworth BeJeebers (anonymous) | Posted March 28, 2007 at 08:31:20

Hey Mark, I don't know if you get a lot of feedback but your writing is right out of this world. RTH is great, but your essays take it to the next level. In your hands, the hammer is a gilted, jewel-encrusted battle ax that's so beautiful your readers don't even notice you've cleaved them in two (that's a compliment btw). Please keep writing!!

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?