Frederick Rastrick designed some of the most iconic buildings of mid-19th century Hamilton.

By Stephen Otto

Published February 26, 2007

![Fig. 1: Portrait of Rastrick as an older man [TPL, The Canadian Album: Men of Canada (1891)] Fig. 1: Portrait of Rastrick as an older man [TPL, The Canadian Album: Men of Canada (1891)]](/static/images/rastrick_01.jpg)

Fig. 1: Portrait of Rastrick as an older man [TPL, The Canadian Album: Men of Canada (1891)]

Frederick Rastrick was born in August, 1819, in the Staffordshire town of West Bromwich, the third son of John Urpeth Rastrick and his wife, Sarah Jervis. [1] By the time of his birth his father had already achieved wide recognition as a skilled pattern-maker, iron founder and civil engineer.

His reputation had been built at the Bridgnorth Foundry, where he turned drawings by pioneers of steam technology like Richard Trevithick into engines, mainly for Cornish mines and West Indian sugar plantations. On occasion he was called upon also to supply cast-iron work for projects like bridges.

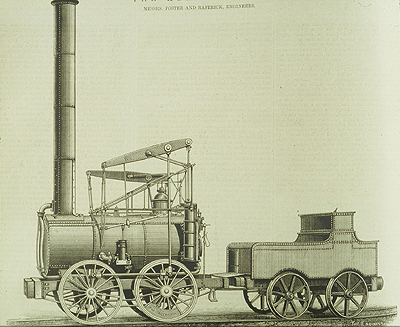

Fig. 2: Engraving of "Agenoria" (slide)

About the time of Frederick's birth, John Rastrick assumed new responsibilities as the managing partner at Foster, Rastrick & Co., a Stourbridge ironworks where more than 450 men made all kinds of machinery, engines, retorts, boilers, rails and the like.

During his time there, the firm was famous for developing and manufacturing some legendary railway locomotives, such as the Agenoria, now the oldest surviving locomotive in the world [2], and the Stourbridge Lion, built for the Delaware & Hudson Railway and the first locomotive to operate in the United States.

![Fig. 3: Rastrick family home on Eaton Square, London [author's photo] Fig. 3: Rastrick family home on Eaton Square, London [author's photo]](/static/images/rastrick_03.jpg)

Fig. 3: Rastrick family home on Eaton Square, London [author's photo]

Rastrick was so eminent that he was invited by the directors of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway to set the conditions and then judge the famous Rainham Trials of 1829 where Robert Stephenson's Rocket demonstrated clearly the advantages of his locomotive design. Also, he was asked to advise parliamentary committees dealing with technical matters and to design some of the many railway lines and structures built in Britain during its first railway boom.

Frederick's upbringing was obviously one of privilege, but few of its details are known. Like other sons of the well-to-do, he went away to boarding school, perhaps somewhere in Yorkshire. In 1837, when the family moved to London, he began working in his father's office where as a draftsman and office boy he picked up a smattering of engineering knowledge.

![Fig. 4: Plate showing St. Jacques, Liege, [Weale's Quarterly Papers on Architecture, v. II] Fig. 4: Plate showing St. Jacques, Liege, [Weale's Quarterly Papers on Architecture, v. II]](/static/images/rastrick_04.jpg)

Fig. 4: Plate showing St. Jacques, Liege, [Weale's Quarterly Papers on Architecture, v. II]

His eldest brother, seven years his senior, worked in the office too and had the inside track on succeeding their father. Both lived at home in the Rastricks' large house at 46 Eaton Square. [3]

In any event, Frederick soon realized he wanted to be an architect rather than an engineer. Accordingly, in January, 1838, through the influence of his father, he was articled to Charles Barry, arguably London's most prestigious architect at that time.

![Fig. 5: Plate showing St. Jacques, Liege, [Weale's Quarterly Papers on Architecture, v. II] Fig. 5: Plate showing St. Jacques, Liege, [Weale's Quarterly Papers on Architecture, v. II]](/static/images/rastrick_05.jpg)

Fig. 5: Plate showing St. Jacques, Liege, [Weale's Quarterly Papers on Architecture, v. II]

Barry's career had begun about 1810 in the office of some surveyors in Lambeth. When travel to the continent resumed again following the Napoleonic Wars, he toured for four years through France, Italy, Greece, Turkey and the Mediterranean islands, studying Classical architecture but particularly the Renaissance buildings of Rome and Florence that later would be models for his important designs for the Travellers' and Reform Clubs.

Although he preferred the Italian style to the Gothic and Elizabethan, his skill in working in the latter modes served him well when, in 1836, he won the competition for the New Houses of Parliament at Westminster. Barry may have come to see his success as a mixed blessing.

The Westminster commission made him famous, and allowed him to gather together a team of talented draftsmen and students to help with the work. They included his two sons, Charles and Edward Middleton Barry, and people like A. W. N. Pugin, George Somers Clark and John Gibson, all of whom Frederick Rastrick came to know.

But the job also dominated his office for twenty years, limiting the number of other commissions he could handle. Among Barry's more notable projects during Rastrick's time were the Reform Club, laying out Trafalgar Square, Dulwich Grammar School, and Highclere Castle, Hampshire.

![Fig. 7: Coppley Apparel (Young, Law) today [David Cuming] Fig. 7: Coppley Apparel (Young, Law) today [David Cuming]](/static/images/rastrick_07.jpg)

Fig. 7: Coppley Apparel (Young, Law) today [David Cuming]

Frederick's articles of apprenticeship were up in January, 1843. On Barry's recommendation, he then enrolled in the Royal Academy Schools to gain access to the lectures on architecture, drawing classes and fine library available there. Casting around for his next move, there is some evidence he considered going to the West Indies, but by November he was in Liège, Belgium, measuring and recording St. Jacques Church for a British architectural magazine. It was no quick study; he hoped he could be finished by the following summer.

The keepers of the church fabric supplied him with original drawings for the stained glass windows, but these had to be reduced for publication. Out went a call to the manager of his father's office for a pantograph to help with the process. As the drawings were finished they were sent off and appeared in Weale's Quarterly during 1844 and 1845. [4, 5]

When that work was behind him, Frederick continued on to study in Paris, Rome, Munich and Vienna, and travelled to Asia Minor and Egypt, "perfecting himself in his profession," as he put it. Thanks to the support given him by an indulgent father (who also supported Frederick's second eldest brother in Paris for more than ten years), he did not return to England until 1848.

![Fig. 8: Coppley Apparel (Young, Law), doorway to courtyard {David Cuming] Fig. 8: Coppley Apparel (Young, Law), doorway to courtyard {David Cuming]](/static/images/rastrick_08.jpg)

Fig. 8: Coppley Apparel (Young, Law), doorway to courtyard {David Cuming]

Even then, he was in no hurry to begin making a living, and spent much of his time overseeing improvements to Sayes Court, a country house near Chertsey, Surrey, where his father planned to retire. Not until 1850 did he move to open an office in London, where he was in partnership with Charles Ainslie. But their firm was short-lived and produced nothing memorable.

Perhaps he had renewed feelings of wanderlust in Spring, 1852, but in any event he left England for Canada and by July had opened an office in Brantford. Why he picked Brantford is unclear.

But only ten months later, just as his career had begun to take off—one of two plans he had prepared for a new Anglican church in town had been accepted—he was summoned home by his father because his eldest brother, who had been confined for some years in a private mental asylum, was dying. Frederick did not return to Canada until October.

![Fig. 9: Coppley Apparel (Young, Law), base of cast-iron column {David Cuming] Fig. 9: Coppley Apparel (Young, Law), base of cast-iron column {David Cuming]](/static/images/rastrick_09.jpg)

Fig. 9: Coppley Apparel (Young, Law), base of cast-iron column {David Cuming]

By then he had probably made up his mind to make Hamilton his base. While he had maintained an office in the city since late 1852, he took up residence here in December, 1853. His first big commission following the move was a large warehouse for Young, Law & Co. at the corner of MacNab and Merrick streets, for which he called construction tenders in February, 1854. [6]

It was his masterpiece and stands today against all odds as the offices and factory of the Coppley Apparel Group. The building is a large one, but its mass is broken up visually by organizing it into pavilions and ranges, and by interrupting the pattern of window openings with a monumental chimney and a gateway to an interior yard. [7, 8] The mansarded roof and chimney are later additions, though not incongruous ones.

Luckily, the building has never suffered a major fire, and has not been the subject of a misguided attempt at modernization. What work has taken place on the interior to create offices on the ground floor has been done carefully to reveal rather than conceal the structural elements.

![Fig. 10: Coppley Apparel (Young, Law), head of column [David Cuming] Fig. 10: Coppley Apparel (Young, Law), head of column [David Cuming]](/static/images/rastrick_10.jpg)

Fig. 10: Coppley Apparel (Young, Law), head of column [David Cuming]

As remarkable as Young, Law & Company's warehouse is on the outside, it is the structure in the interior, which depends on some of the earliest cast iron columns used anywhere in Canada, that gives it particular distinction. The columns sit on blocky octagonal bases and rise, through long, reeded shafts, to octagonal capitals supported on decorative collars of lotus leaves. [9, 10] The idea for the design might have come directly from Stuart & Revett's Antiquities of Athens, since Rastrick owned an original edition.

Probably the columns were cast right here in Hamilton, likely at McQuesten & Co's. Foundry, only a block away at James and Merrick. [11] While foundries in the area had been making stoves, mill equipment and agricultural implements since the 1830s, it was the building and equipping of the Great Western Railway in the early 1850s that attracted large amounts of capital and scores of experienced craftsmen to Hamilton, and set it firmly on the road to becoming Canada's preeminent place for iron-founding and steel-making.

![Fig. 11: Engraving of McQuesten's Foundry [TPL, Baldwin Room, T-14639] Fig. 11: Engraving of McQuesten's Foundry [TPL, Baldwin Room, T-14639]](/static/images/rastrick_11.jpg)

Fig. 11: Engraving of McQuesten's Foundry [TPL, Baldwin Room, T-14639]

Two years after Young, Law & Co. had occupied their new quarters James McIntyre, a wholesale grocer who was also John Young's brother-in-law, erected a warehouse of nearly identical design further north on MacNab Street. Separated from the former building by a narrow lot, it appeared as a continuation of it. The only significant differences in appearance of the two structures were ones of scale, and how their roofs were treated.

McIntyre's building was only three bays wide, compared to its neighbour's fifteen bays, and had a pitched roof rather than a flat one. Based upon a published tender call for its construction, Rastrick is known to have prepared the plans.

![Fig. 12: Bank of Upper Canada [Archives of Ontario, AO 6177] Fig. 12: Bank of Upper Canada [Archives of Ontario, AO 6177]](/static/images/rastrick_12.jpg)

Fig. 12: Bank of Upper Canada [Archives of Ontario, AO 6177]

A few months later, in July 1856, the architect invited proposals for building the Hamilton branch of the Bank of Upper Canada at James Street North and Vine. [12] His plans (like those for most other banks built in Canada at that time) borrowed heavily from Charles Barry's designs for the Reform Club in London developed during Rastrick's time in his office.

As he worked up the bank drawings, Rastrick may have felt an acute sense of deja vu. Barry's clubhouse was inspired by the palazzos of renaissance Italy, but its form also proved well-suited to banking because it oozed stability, allowed functions to be organized rationally, and recalled in a symbolic way the roots of modern commerce in Florence and Milan.

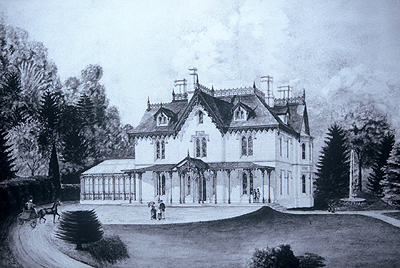

Fig. 13: Watercolour perspective of "Highfield" [Private Collection]

The banking room, vaults and private offices were on the ground floor while there was a roomy apartment for the manager on the upper floors. This hierarchy was reflected on the exterior. Wall surfaces and window openings were plainer on the second floor and even more modest on the third.

It would be satisfying to report that dozens more of Rastrick's works of the 1850s have been identified through a patient scanning of local newspapers for tender calls. This is not possible, however, since he seldom took this route in awarding contracts.

Besides the three buildings noted above, only one other significant commission has been confirmed through a published tender call: a Gothicized house for John Brown erected at the foot of Bay Street in 1858, when Rastrick was in partnership with William Hall and Daniel Berkely Wily. [13] Known as "Highfield," the house was later the residence of Sir James Turner, and later still Highfield Boys' School.

![Fig. 14: Griffin House [Hamilton Public Library, Special Collections] Fig. 14: Griffin House [Hamilton Public Library, Special Collections]](/static/images/rastrick_14.jpg)

Fig. 14: Griffin House [Hamilton Public Library, Special Collections]

The news and editorial pages of the newspapers have proved equally unyielding. During the first decade Rastrick lived in Hamilton his name appeared only once in the local papers as the architect for a project that was the subject of a report. That was in a detailed description of the Bank of Upper Canada that appeared in The Spectator. Of course, if Rastrick's drawings, his job list or a diary survived, there would be no need to rely upon tender calls and newspaper reports.

But no significant group of his papers is known, probably because they were destroyed in a 1923 fire that consumed the office in the Lister Block where two of his sons, both architects, continued his practice. The only drawing known to exist that is signed by him points to his authorship of the designs for a house on Charlton Avenue, known as "Hawthorn Lodge" when the Griffin family lived there in the 1870s. [14]

![Fig. 15: Ambrose house [Hamilton Public Library, Special Collections, Arthur Wallace] Fig. 15: Ambrose house [Hamilton Public Library, Special Collections, Arthur Wallace]](/static/images/rastrick_15.jpg)

Fig. 15: Ambrose house [Hamilton Public Library, Special Collections, Arthur Wallace]

To understand more fully Frederick Rastrick's place in the development of Hamilton in the 1850s, the only choices left are to examine some circumstantial evidence, and to have recourse to the unreliable stratagem of stylistic attribution.

Consider first the circumstantial evidence, slender though it is. In 1858 Messrs. Rastrick, Hall & Wily took out advertisements in newspapers and in a handbook published to coincide with the Provincial Exhibition in Toronto that listed gentlemen who could speak to the firm's professional capabilities.

The inference was that many of the gentlemen were clients. Although there were slight differences in the lists, they included names like Sir Allan MacNab, William Ambrose, Richard Juson and William McLaren.

![Fig. 16: Juson Warehouse [National Archives of Canada, C-8860] Fig. 16: Juson Warehouse [National Archives of Canada, C-8860]](/static/images/rastrick_16.jpg)

Fig. 16: Juson Warehouse [National Archives of Canada, C-8860] (click on the image to view larger)

The reference to Sir Allan MacNab is ambiguous. It may reflect work undertaken at "Dundurn," for which there is scant evidence apart from oral tradition, or may refer to Sir Allan's patronage of Rastrick which secured for him a commission to design Hamilton's Custom House, though not the one standing on Stuart Street today. The inclusion of William Ambrose's name could relate to the somewhat Gothic house he built on Charlton Avenue next door to the Griffin house. [15]

The mention of Richard Juson prompts consideration of two important buildings associated with him, "Arkledun," his home on John Street South near the Mountain, and an impressive warehouse on James St. South where he conducted his hardware business. [16]

"Arkledun" can be ruled out as being Rastrick's work, however, because it appears on a 1851 map of Hamilton, before he had settled here. But the warehouse, erected in 1853, was a very careful piece of Italianate design that could not have come from an untutored hand.

![Fig. 17: McKeand Bros. Warehouse [National Archives of Canada, C-7260] Fig. 17: McKeand Bros. Warehouse [National Archives of Canada, C-7260]](/static/images/rastrick_17.jpg)

Fig. 17: McKeand Bros. Warehouse [National Archives of Canada, C-7260]

Organized horizontally into basement, piano nobile and attic, with each level being set off by a sill-course or different degree of architectural richness, it showed a Palladian sensibility, emphasizing the central bays on the second and third storeys by a change in the plane of the wall, quoining, and a gable.

Although Rastrick was in England for much of 1853 nothing would have prevented his designing the building before he departed, and leaving the supervision of its construction to others. Stylistically similar to Juson's warehouse, and probably designed by the same architect, was the row of warehouses erected in 1858 by McKeand Brother & Co. on MacNab Street north of Merrick, beside the Methodist Church. [17]

![Fig. 18: Burlington Terrace, Herkimer St. [David Cuming] Fig. 18: Burlington Terrace, Herkimer St. [David Cuming]](/static/images/rastrick_18.jpg)

Fig. 18: Burlington Terrace, Herkimer St. [David Cuming]

William McLaren was Juson's brother-in-law, and if he made Rastrick's list as a client rather than as a reference, likely it was on account of the three units of Burlington or Herkimer Terrace he put up in the mid-1850s. [18] A fourth unit was built by F.W. Gates. The terrace also has some stylistic imprints closely connected with Rastrick, and to these we now turn.

After Rastrick married Anna Mary Stephens in the Church of the Ascension in July, 1857, they made their home at 22 Maria Street, now 46 Forest Avenue, where they would live the rest of their lives. [19] Almost certainly he designed this house, which provides clues that help identify other buildings likely by his hand too.

![Fig. 19: Rastrick family home, Forest Ave. [David Cuming] Fig. 19: Rastrick family home, Forest Ave. [David Cuming]](/static/images/rastrick_19.jpg)

Fig. 19: Rastrick family home, Forest Ave. [David Cuming]

The motif of rosette-like pateras over the main doorway at 46 Forest Avenue, is also used to decorate a long-demolished house at 226 York Street [20], one still standing at 120 Park St. North at Cannon, the upscale Burlington or Herkimer Terrace [21], and even a commercial building at 22 King Street East. [22]

The house at 120 Park North also has unusual bayed dormers. [23] While these are common in Nova Scotia, where they are sometimes called Scottish dormers, they are seldom seen in Ontario. But bayed dormers were used on several mid-19th century buildings in Hamilton, for example, a house on Robinson west of MacNab taken down in 1960, an otherwise unremarkable brick dwelling off Cannon Street, and on the well known and distinguished Sandyford Place on Duke Street. [24]

![Fig. 20: 226 York St. {Hamilton Public Library, Special Collections] Fig. 20: 226 York St. {Hamilton Public Library, Special Collections]](/static/images/rastrick_20.jpg)

Fig. 20: 226 York St. {Hamilton Public Library, Special Collections]

While it is a big step, from finding bayed dormers, a masterful massing and skilful handling of Italianate elements at Sandyford Place to saying that this terrace is Rastrick's work, that is the likely conclusion if the argument were made at greater length.

Having looked at some buildings of the 1850s having strong or stylistic connections with Frederick Rastrick, consider now some situations where no connection has been proven yet, or the mistake is made of attributing the design to him routinely in spite of evidence to the contrary. In the first category is "The Castle," sometimes known as "Amisfield." [25]

Located on more than an acre of land it was built over a four-year period by Colin D. Reid, a bachelor lawyer and agent for Peter H. Hamilton. The walls were standing by 1854, but then construction slowed and was not pushed to completion until 1856.

![Fig. 21: Burlington Terrace, Herkimer St. [David Cuming] Fig. 21: Burlington Terrace, Herkimer St. [David Cuming]](/static/images/rastrick_21.jpg)

Fig. 21: Burlington Terrace, Herkimer St. [David Cuming]

Given this time frame, there is no reason Rastrick could not have been Reid's architect; certainly he was in the area. But he does not include Reid's name on his list of references, and no other connection between him and "The Castle" has been found. Parenthetically, if ever a case could be made for moving a building to another site to preserve it, surely this is it.

From the late 1940s, when the annex known as the Castle Building was added on the north, to the present day that has seen it engulfed by mediocrity, "The Castle" has been a textbook example of indifference to architectural quality.

Hamilton's Custom House is in the second category of buildings, which were not designed by Rastrick but are frequently credited to him. Here the confusion is understandable. He made not just one, but two designs for a Custom House in 1855 and 1857, only to see them set aside because the budget was insufficient or the Government changed its mind.

![Fig. 22: 22 King St. E. [David Cuming] Fig. 22: 22 King St. E. [David Cuming]](/static/images/rastrick_22.jpg)

Fig. 22: 22 King St. E. [David Cuming]

When the Government decided in 1858 to proceed, Frederick P. Rubidge, an architect with the Board of Works, was directed to prepare the plans. [26] Rastrick struggled for years to recover some portion of the fees he had lost in this turn of events.

He also prepared and in June 1854 was paid for designs for a new Canada Life office on James Street South. But the company seems to have had a change of heart, because in 1855 it accepted the terms of the firm of Sage & Barger of Buffalo to make all plans and drawings, take general superintendence of the job, and visit as often as necessary, say every two to four weeks. [27]

Not long after Rastrick's marriage in 1857, the United States and Canada were plunged into a commercial depression that was longer and deeper than anyone had experienced before. He would not have known then, but the best years of his career were behind him. The population of Hamilton, which had grown from 9,900 in 1848 to about 25,000 in 1857, fell back to 19,000 in 1861.

![Fig. 23: 120 Park Ave. N. [David Cuming] Fig. 23: 120 Park Ave. N. [David Cuming]](/static/images/rastrick_23.jpg)

Fig. 23: 120 Park Ave. N. [David Cuming]

The outbreak of civil war in the United States only made matters worse. In 1856 and early 1857 Rastrick had been led to believe that his appointment to the staff of the Provincial Board of Works was pending, and he let his practice slide.

By the time he learned no appointment was in the offing, it was too late to recover. On several occasions over the next decade he renewed his attempts to get the Board to hire him, without success. The in-basket of Hamilton's member of Parliament, Hon. Isaac Buchanan, overflowed with letters from Rastrick begging Buchanan to use his influence to get him work.

He even sought an appointment to supervise the construction of the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa after the original architects were discharged for cause, but was passed over.

![Fig. 24: Sandyford Place [David Cuming] Fig. 24: Sandyford Place [David Cuming]](/static/images/rastrick_24.jpg)

Fig. 24: Sandyford Place [David Cuming]

In 1861 Rastrick gave up his office and began working from his house, adding the services of Land, House and Commission Agent to what he offered. One of the properties he was entrusted to sell was "Chedoke."

Its owner and Rastrick's close friend, Charles John Brydges, had been on his list of references. But he continued to find things difficult, and in 1867 on account of poor health and "a perfect dearth of employment" he made the difficult decision to offer his prized architectural library for sale. [28]

Fig. 25: "Amisfield" [Hamilton Public Library, Special Collections]

It consisted of more almost 150 rare leather-bound volumes acquired in the 1840s, and was undoubtedly the finest collection of its kind in the country. In the ensuing few years he even found it necessary to spend part of his time practising in Montreal.

His health had begun to give him difficulty too. Apparently his problem was sciatica, which laid him up regularly. He was off work "for some while in 1864;" for eighteen months in 1871; and for another several months in 1872. On two other occasions, he came near to losing his life. In 1866 while returning from the Contractor's Pic-Nic at the Beach the cab in which he and others were riding was struck by a train at a crossing.

![Fig. 26: Custom House [National Archives of Canada, PA-164441] Fig. 26: Custom House [National Archives of Canada, PA-164441]](/static/images/rastrick_26.jpg)

Fig. 26: Custom House [National Archives of Canada, PA-164441]

Rastrick was thrown clear, but one of the ladies in the party was killed. Three years later, when he was in his office in Montreal, the roof of the building collapsed from the weight of snow, and he was barely able to scramble down a stair to safety.

Only two significant projects can be attributed to Rastrick during the last thirty years of his life. In 1866 he was responsible for designing Hamilton's new Caroline Street Grammar School. [29] It was enlarged subsequently to serve as the Hamilton Collegiate Institute. And in 1872 he was retained by the Church of the Ascension as the architect for a new Sunday School building. [30]

![Fig. 27: Canada Life, James St. [National Archives of Canada, C-5077] Fig. 27: Canada Life, James St. [National Archives of Canada, C-5077]](/static/images/rastrick_27.jpg)

Fig. 27: Canada Life, James St. [National Archives of Canada, C-5077]

Tenacity marked Rastrick's character, and came out in his attempts to create a professional body for the architectural profession. In 1860-61 he had been a vice-president of the newly-founded Association of Architects, Civil Engineers and Public Land Surveyors of Canada.

Fourteen years later he was the first president of the short-lived Canadian Institute of Architects. Finally, in 1889 when the Ontario Association of Architects was established, Rastrick was appointed by the lieutenant-governor to its inaugural council.

A gregarious man, he was active also in the Mechanics' Institute, Sons of England, St. George's Society and the Acacia Masonic Lodge. He had become a Mason shortly after settling in Hamilton in 1854. A founder of the Acacia Lodge, he later served as its Master.

Frederick James Rastrick died on 12 September 1897, and was buried in the Christ Church section of the Hamilton Cemetery. No stone now marks his resting place and that of eight other members of his family.

![Fig. 29: Caroline St. Public School [Hamilton Public Library, Special Collections] Fig. 29: Caroline St. Public School [Hamilton Public Library, Special Collections]](/static/images/rastrick_29.jpg)

Fig. 29: Caroline St. Public School [Hamilton Public Library, Special Collections]

By adrian (registered) | Posted February 26, 2007 at 13:25:17

What an absolutely fascinating article. It's great to peel back some of the layers of Hamilton's history and find such remarkable stories, and it's inspiring to read about such a tenacious individual.

By peter (anonymous) | Posted February 27, 2007 at 15:16:48

so depressed. so very depressed. that said, a few of these old beauties still exist. good article.

By Edward Smith (anonymous) | Posted March 10, 2007 at 22:51:21

You state that there is no evidence of Frederick Rastrick working on Dundurn for Allan MacNab - yet Marion MacRae in her 1971 book takes this as fact - that Rastrick designed the 1855 portico. Sadly, her book has no references.

By Gareth Williams (anonymous) | Posted July 10, 2007 at 10:13:19

I was particularly interested to read about Richard Juson's warehouse. I own a flat in a house called The Monklands in Shrewsbury, England, to which Juson retired with his wife Harriet. Having been benefactor to the Church of the Ascention in Hamilton, Harriet went on to pay for much on J.L.Pearson's rebuilding of Shrewsbury Abbey.

Thank you for posting the article.

By A.D.L. (anonymous) | Posted November 17, 2008 at 14:53:47

I am curious if there is any more evidence out there on the Juson home "Arkledon"

By scubahood (anonymous) | Posted January 03, 2010 at 11:59:07

thanks for this.. i live in fig. 25 and it's the most gorgeous .. i'm always eager to learn more about it!

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?