Can we achieve additive, not subtractive, reurbanization, and retain the mass, variety, and cohesion of a 'real city'?

By Shawn Selway

Published September 29, 2015

Edward Relph, Toronto: Transformations In A City And Its Region. University Of Pennsylvania Press, 2014.

In the previous instalment, we looked at a couple of subjects that stood out for me in Relph's tale of Toronto transformation: the "three cities" map of income trends, and the course of intensification in downtown Toronto so far.

To continue, I want to discuss Relph's treatment of the question of centrality.

Relph is concerned with the phenomenological bases of geography. Those wishing to know more about that should consult the papers he has uploaded to his page at Academia. Suffice to say that he is interested in the individual's pre-theoretical, direct experience of place and time (assuming such a thing is possible) and is a persistent walker, cyclist and motorist who likes to go everywhere and look at everything for himself.

As mentioned, he regards the denigration of suburban "sprawl" as reflexive cant, uninformed by observation. When he goes and looks, he finds a landscape that is decentralized, with services no longer concentrated in Toronto and Hamilton as in 1960 but scattered over a wide area whose original towns remain within nominal boundaries that are "for most purposes virtually invisible and utterly permeable"; in short, non-existent.

In this context, Relph discusses the highway system which allows the flows within the "evolving urban form" that is the "polycentric city" - one which is apparently quite to the satisfaction of its residents.

Superimposed upon this space are the farflung networks of commercial retail outlets, each one a node just like all the others in the Tim's net or the Home Depot net. The disconnection from the particulars of locality is completed by electronic media acting within "post-polycentric electronic fields". Consequently, we now have a world of:

three superimposed urban forms in the Toronto region - the mostly monocentric one focused on the core of the old city, a polycentric one with many overlapping networks, and an amorphous, still poorly understood, post-polycentric one. In other words, the urban region of Toronto is simultaneously centralized and decentralized, spread out and concentrated, networked and dispersed. In these respects it is a microcosm of the processes that are associated with globalization.

Globalization meaning, as Relph goes on to explain, flows of all kinds, not only of money and goods but of people, and also meaning the aggressive competition which is everywhere intensifying social inequalities.

(I'm not sure that "competition" is the right word here; the way I read the newspaper, "corruption" would seem more apt, both of the state authority whose role is to mitigate the damages of capitalism, and of the financial systems whose role is to ensure that risk has consequences that discipline all participants.)

The reader may feel that saying that greater Toronto is everything and nothing is not saying much, and the apparent analytical meltdown I have quoted does suggest that a new departure is needed to encompass so much variety and contradiction. One might want to experiment with an approach that dropped the contrast between an inner and an outer city altogether, and view urban life as a nested series of more or less mediated experiences, considered across a range of media and their vehicles.

For example, one could think about the devices which would appear on a line drawn between solipsism and conviviality. I suppose that the car would be on the solipsistic end, and the cellphone on the convivial, and so on.

Or one could simply jump directly from consideration of the polycentric to cyberspace and chart that very changeable terrain, which will remain "spatial" and therefore "geographic" as long as we continue to think analogically, that is in terms of high, low, near, far, clear, obscure and so on.

In this rapidly growing world-girdling megalopolis of the ether, individuals and their institutions, whether publicly or privately owned, vie for scarce attention and struggle to become central and avoid relegation.

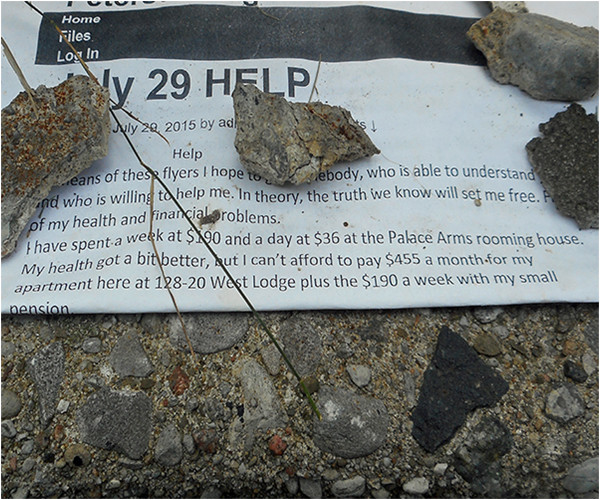

This Parkdale resident competes for attention and influence with seven hundred thousand other Torontonians.

The flier in the image above is a page print from the individual's Wordpress blog. On his site he discusses his housing problems and the general political situation, presents his sessions of divination using the I Ching, and recommends various articles in the print media to his readers.

In short, like almost everyone else from the managers of Google through the lackey responsible for this or that politician's twitter account to the aspiring ten year old rappers and violinists who throw stuff up on Youtube and Vimeo, this person is trying to increase his centrality. He is striving to gain attention and exert influence over others, though possessing very limited capital.

To effectively enlarge himself, he might best add his own efforts to those of his fellows, for example via a tenants' association in his neighbourhood, which will then seek to use the new media as part of its attempt to become central and influential by drawing attention to its proposals.

A couple of implications present themselves. First, the persistence of the landlord-tenant symbiosis rather obviously points us to enduring forces shaping all these geographies at all levels of description. In adopting an ecological perspective, Relph set aside a leading topic of ecological analysis: the tracing of energy flows within the systems which they also constitute.

In the case of our species, the physical and mental powers of the organism are both living and "dead". That is, they are available to us both immediately, as, for example, the capacity to design and build a chair, and externally, as the completed chair, which, once made, I have and can trade, sell, give or otherwise send through the larger system in which I am embedded. Ditto my apartment building or whatever.

Secondly, if the tenants association were to follow the new member's lead and use Wordpress to spread their message, they would be reinforcing the centrality of a corporation which claims to be a quarter of the internet and for that reason possesses a great deal of attractive power.

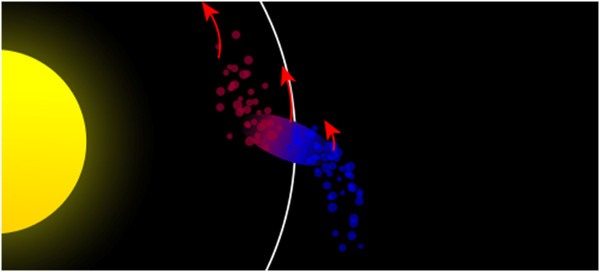

This, in turn, suggests to me another way to look at centrality, namely, in terms of tidal forces - that is, the forces which operate between bodies large enough to exert reciprocal pulls.

The Roche limit, defined by Edouard Roche in 1848, was his contribution to speculation on the origins of the rings of Saturn. Roughly, it is the minimum distance between a primary and a secondary body, within which limit tidal forces will cause the secondary body to disintegrate - depending on its comparative size, its composition, and the tensile strength of its materials.

From this metaphorical perspective, the "post-polycentric" region of no margins or boundaries looks like so much rubble orbiting Toronto-Mississauga and the airport district. Centres may not matter to you if you think you are at one, but they may matter a great deal if you are in a satellite threatened with reduction to a ring of debris.

Roche limit exceeded. Image: Theresa Knott, Wikipedia.

It is evident that central Hamilton is being re-structured by tidal forces that have become more consequential than the official plans, or at least, the planning powers which are actually being exercised.

Let me switch into Business Inspirational mode and ask: How can we preserve structural integrity and improve our cohesion? How can we maintain the social fabric and the built fabric, and keep them complicated and diverse? In a word, How can the Hammer increase its tensile strength?

We could start by opposing displacement.

Back in 2009, academics in the University of Toronto's architecture department aggregated several years worth of their work in a document titled Tower Renewal Guidelines for the Comprehensive Retrofit of Multi-Unit Residential Buildings in Cold Climates. They were responding to a serious emerging problem: what to do about the large stock of fifty-year old concrete towers in the GTHA which were coming due for repairs.

The following year the provincial Growth Secretariat released a companion report, Tower Neighbourhood Renewal in the Greater Golden Horseshoe, which it had commissioned from a pair of Toronto consulting firms.

The gist of this report is that rehabilitation of those high-rises could be financed in part by building on under-used land in the immediate vicinity of the towers - a move which could also enhance the quality of the life of the existing residents by providing new amenities, once the zoning had been relaxed as necessary.

As always there are complications, and the authors of the report had this to say about what they termed "economic eviction."

A key aspect of Tower Neighbourhood Renewal's success internationally has been the improvement of the quality of housing within existing Apartment Towers, as well as the introduction of new housing and amenities within tower neighbourhoods. This raises a challenge with respect to maintaining housing equity and affordability in the face of Tower Neighbourhood Renewal. Specifically, how to ensure that economic evictions do not occur as a result of Tower Neighbourhood Renewal and that Tower Neighbourhood Renewal expands housing choice for existing Apartment Tower residents. To address these challenges, further study is required to determine:

- methods for ensuring affordability post-renewal;

- methods for minimizing tenant discomfort during the renewal process; and

- methods for ensuring that displacement does not occur as a result of renewal.

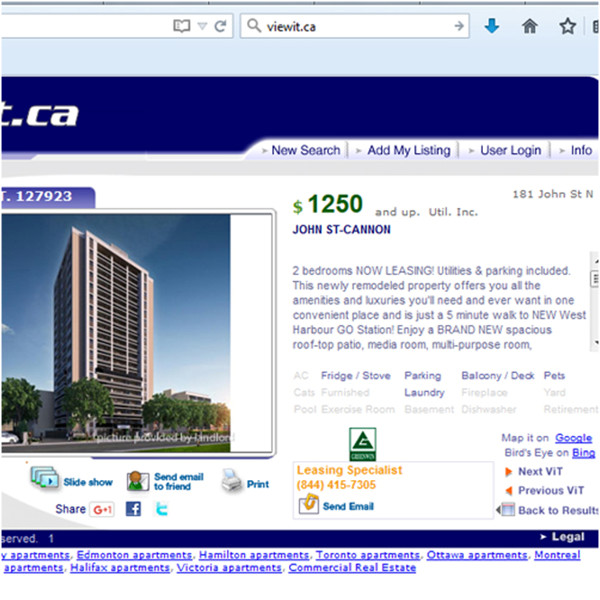

None of which last would seem to have been done here, since displacement on a large scale is going on in Robert Village (181 John, 192 Hughson, 44 Robert) despite wishes for the contrary such as that uttered recently by one of the principal authors of the Tower Renewal report.

Jason Thorne, now heading the Planning and Economic Development department here in Hamilton, told the Spectator apropos of a development on Cannon Street, that "We don't want downtown to be a single demographic area. We want seniors; we want students; we want families; we want people of all incomes."

Just so, and in saying this Thorne is simply repeating official city policy, as stated in the following paragraph from the Urban Hamilton Official Plan.

Policy E.2.3.1.6 The Downtown Urban Growth Centre shall function as a residential neighbourhood with a large and diverse population. A range of housing types, including affordable housing and housing with supports, shall be encouraged as set out in the Downtown Hamilton Secondary Plan and other associated secondary plans and policies of this Plan.

Nonetheless, more than half of the units in the two 18-storey buildings of Robert Village have become vacant.

Screen grab from viewit.ca

It is clear that unless tenants organize themselves to insist on proper maintenance and rehab of their buildings, and also to resist large above-guideline rent increases, they will find themselves being pushed out of their homes into a market of steadily rising rents, and spending an even greater proportion of fixed or shrinking incomes on housing.

We could defend areal planning against site-specific zoning and require proportionality in benefit-for-density arrangements allowed under Section 37 of the Planning Act.

The greatest difficulty with off-plan proposals will likely be those involving an affordable housing component, however that is defined, because this is becoming a warm political issue.

In the absence of provincially-mandated inclusionary zoning rules, the City will probably be trying to use section 37 to secure below-market-value units - or rather, proponents will be attempting to increase the number of market value units they can build by offering affordable units in exchange for height.

But, as discussed in the first part of this review, the experience of downtown Toronto shows that height is not the one best way to obtain density.

In this regard the Tivoli deal is a bellwether. The proponent of that project was given a height increase by Council over the objections of planning staff, in exchange for a notional rehabilitation of the shuttered theatre on the site.

I have not seen the zoning bylaw which was written to implement Council's planning decision, nor any accompanying explanations, but the application materials submitted by the developer's agents contained no clear explanation of who was to be responsible for the restoration of the theatre auditorium, in support of which the developer was committed to supplying lobby and other ancillary space.

This oversight may now have been remedied; I don't know. The point is that as presented back in March, this was a density bonus for a benefit deal, in which the benefit was not well defined.

But more importantly, it was a deal from which any concept of proportionality was absent. The developer obtained the right to put up a 22-story building on a site zoned for four to six, but the relationship between the cost of the benefit - the theatre-and-lobby part of the deal - and the value of the extra stories is nowhere discussed.

In this case, the theatre may or may not be rescued, and its managers may or may not come up with a business plan that ensures its longer-term survival, but the crux is that this parcel of downtown Hamilton was effectively planned by three people: the developer, his architect, and the ward councillor.

This is the Toronto system, and we should reject it. There it has become so prevalent that it amounts to a licensing program in lieu of a municipal plan - instead of planning, the City simply charges a fee for density. However, as discussed in the first part of this review, the experience of downtown Toronto shows that height is not the one best way to obtain density, and that, for a number of medium and long-term reasons, coverage is probably preferable to height.

Production, and in particular manufacturing, continues to be visibly present in the lower city of Hamilton as it simply is not in Toronto. When Relph discusses manufacturing, he takes us to the outer suburbs in the vicinity of the airport, a ten-mile wide area of "featureless sheds" containing production and warehousing facilities, as well as the Canadian head offices of thirty corporations. No one lives out there.

Here it is quite different. Residential districts are hard by unbuffered steel lands and other light and heavy industrial plant, and a stock of mostly sturdy disused industrial buildings is dispersed over a broad stretch of the central city. Some are very large, and their adaptive re-use could perhaps be hastened by subdivision, in order to permit the smallholder ownership which has brought back main streets like James and Ottawa and appears to be finally helping the repair of Barton.

Toronto, with its regional industrial district in the foreground. Image: torontotransforms. com. This is the companion website for Relph's book and contains much supplementary material, including essays added since the book was published.

Uniquely, production continues in the very centre of Hamilton, not only in the west end of Barton Tiffany where heavy industry has operated continuously since Macnab's Great Western Railway set up shop there in 1854, but also four blocks from city hall at Cambridge Clothes on York and two blocks northeast of that, at the Firth Brothers building on Hughson.

The existence of these facilities - both of which have very handsome fronts on the street - along with design studios, vintage shops and a sewing school on James, means that we have a bona fide garment district downtown, serving to affirm a productivist ethos which offsets a little the casino mentality of real estate appreciation about which we hear so much.

Leaving aside the so-called Steel Lands - the 300 hectares from which US Steel is presently squeezing the last few drops of blood - the lower city is a patchwork monument to the first age of industry and the local wealth it generated.

This legacy includes a large complement of open space. Generally fenced and signed, these parked properties come to be regarded as commons and used and misused accordingly.

A bundle of "brownfield" financial incentives mandated by the Section 28 provision for Community Improvement Plans is available to investors whose devotion to the "free market" is not perfect, but they do not include any interim measures that would be of immediate benefit to we who are fronting the dough. Instead, we are treated to the endless contemplation of extensive waste areas representing our decline as an industrial town.

Anyone who wants to feel left behind or have their civic pride ground down a little further has only to step up to the chainlink and look at another heap of overgrown ruins - and if you are drawing a little consolation from the fact at least the area is greening up, go back the next week. You will find that the bee-thick clover has been mowed and all other vegetation cleared and bleak nothing restored.

Meanwhile, superstitious dread hovers over terrain sterilized by the stigma of an industrial past whose details are never investigated, or if learned, left unpublished, so as neither to justify nor refute the fears.

Something else is needed, something to signal transformation - some set of interim measures that could begin to remediate the soil, where needed, and beautify and bring those vacant tracts back toward production. But rather than developing such an approach and selling it with the current jargon, the City is going in the opposite direction, continuously degrading its own holdings in the Barton Tiffany precinct of the West Harbour.

After clearing the land of houses and small business structures as well as industrial buildings, Council permitted construction waste and excess soil to be dumped there for a year, and then allowed snow removal crews to deposit street scrapings from as far east as Sherman Avenue on the site.

Building on the legacy of the Barton Tiffany lands.

Evidently the City is tacitly following the advice of a local architect to leave the area unimproved and ugly in order to encourage acceptance by those living nearby of any development proposal whatever. The effect on the market value of property in Strathcona north seems to matter to no one - including, rather surprisingly, the owners of those houses, and the prospect of Council expanding its empire of dirt onto the CN rail yard is not a pretty one.

Certainly we have to accept that ceaseless modification, expansion and replacement is the fate of all urban fabric.

The spatial arrangements of buildings, streets and open areas which form the more or less stable backdrop to our lives, the places where we meet, work, and shop; which we own and improve; which we used to own; which we will never own but take pleasure in admiring or deploring; all of this we are accustomed to think of as "our city".

But of course, almost none of it is "ours", nor is much of it very stable. A good deal of it is subject to the wishes of very blase nihilists, frequently spouting the progressivist rhetoric of the day as they go about their work of "creative destruction."

Nominally we have some say in what occurs via the planning authority vested in council by the province, but since councillors are rather agnostic toward public plans and eager to accommodate investors on their own terms, the practical effect of that power is wildly irregular. Change has been hesitant here for many years, but now has become quite rapid. Can it be change that is "ours"?

Can we keep our city from being simplified away until nothing is left but a network of identical nodes like those which Relph finds in the outer suburbs of Toronto; or, to put it as Relph's tutelary spirits and fellow Torontonians Jacobs and McLuhan might, can we protect the "organized complexity" and integral diversity of our little corner of the globalizing village against great pressures to erase and simplify and segregate by income?

Additive reurbanization: the 1923 school is retained and enlarged upward, the 1860 Customs House is retained and adaptively reused, the 1931 rail station from which the photo was taken is retained and adaptively reused, and the 2015 GO transit station is inserted into the rail corridor already amended with a fibre optic trunk and a cellular tower. The result is a Pageant of Progress that would gladden the heart of the most philistine of municipal politicians.

Can we achieve additive, not subtractive, reurbanization, and retain the mass, variety, and cohesion of a "real city"?

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?