Heron's new book offers plenty of fascinating detail into the experiences of working class people in Canada's largest industrial centre during a period of tremendous social and cultural upheaval between the 1890s and the 1940s.

By Paul Weinberg

Published September 23, 2015

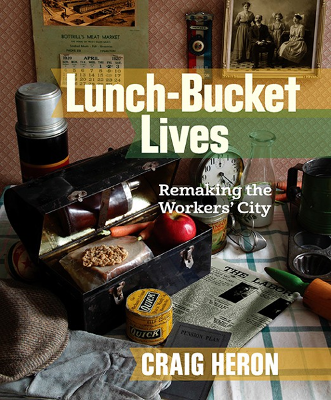

Craig Heron, *Lunch-Bucket Lives: Remaking the Workers' City*, Between the Lines (2015), 784 pages, $39.95

No reporter from the Hamilton Spectator or CBC Hamilton covered the June 24 book launch of *Lunch-Bucket Lives: Remaking the Workers' City* at the Workers Historical and Cultural Centre in the city's historic north end. Nor did they seek an interview with the book's author, York University professor and labour historian Craig Heron.

It is a bit of a shame because local history is popular here in Hamilton, and Heron's new book offers plenty of fascinating detail into the experiences of working class people in Canada's largest industrial centre during a period of tremendous social and cultural upheaval between the 1890s and the 1940s.

Lunch-Bucket Lives culminates Heron's decades of research into Hamilton's blue-collar past that began with his 1981 PhD dissertation. His book is part of a grand tradition of social history scholarship that draws inspiration from The Making of the English Working Class, the classic 1960s work by British historian E.P. Thompson.

One explanation for the media no-show is that, at 700-plus pages, Heron's book is not a quick and snappy read. Another is that the book's theme may be out of synch with the city's post-industrial mood.

The legacy of Hamilton's once predominant manufacturing has not totally disappeared. Approach the city from the Burlington Skyway and you'll see active smokestacks next to empty hulking structures in the vicinity of the harbour. Labour Day still draws a significant crowd and there are still thousands of families living here on union pension plans.

But it is also a city (numbering half a million) where medical services and McMaster University are the major employers, where the older lower city is undergoing a real estate boom (courtesy of Torontonians fleeing a million-dollar home market), and where, according to one local slogan, "Art is the New Steel."

This resetting of Hamilton's image is not new, explains Heron, who titled his book as an ironic counterpoint to a 1971 official commemorative history of the city, Pardon My Lunch Bucket.

So why read a book about a Hamilton that longer exists? Well, as Heron proposes, we can learn a great deal about ourselves today from understanding the past. He writes about a period before the advent of welfare, unemployment insurance or even serious laws legalizing unionization to help those falling through the cracks.

A similar sense of vulnerability has returned to Canada following the weakening of social service supports at all levels of government during and since the 1990s. A growing proportion of the work force (more than half in Hamilton, according to a recent United Way/McMaster study) is locked in temporary, contract or part-time positions.

There were also important economic differences in Canada at the beginning of the 20th century.

By 1900, Hamilton had its ample share of home-grown manufacturers, especially in steel and textiles, which eventually consolidated into larger companies. Local business leaders had a lot of say in the city's economic development, and that included the "coaxing" of manufacturers to set up factories here or to open up a local bank, says Heron.

Labour unrest was endemic because of the appalling working conditions, including long hours and the speed-up of production in the factories. But unions had difficulty gaining a permanent foothold in workplaces in the face of employer resistance. For a working male breadwinner, getting fired for union activity meant destitution for the entire family.

"Hamilton is a very depressing city," said one communist organizer during a brief visit in 1928. Another lamented the almost complete absence of unions, especially in the large plants: "When workers were questioned as to their conditions and wages, it became obvious what a paradise Hamilton is for the employers of the continent."

But working class people had other ways to express their grievances toward industrial paternalism, particularly at the ballot box during the First World War years, where they elected Independent Labour Party candidates locally and at other levels of government. As Heron explains, a farmer-labour coalition came to power in Ontario in 1919, but it was undone by differences over such issues as the eight-hour day and prohibition.

Heron points to how Hamilton elites opposed what they saw as excessive democracy manifesting itself on an elected city council. In response, boards staffed with business people and experts were hived off to take charge in sensitive areas like technical education, hydroelectricity and parks to ensure administrative "efficiency." One prominent labour-leaning politician and future mayor, Sam Lawrence, came under fire in 1932 for being overly generous in the handing out of relief cheques.

Heron also mentions a general trend across North America to control the behaviour of the working class by nurses and social workers and other helping professionals. Within the rigid schooling programs a failure to conform or perform could get a child labelled "abnormal." A city mental health official told a local audience in 1929 that half the city's schoolchildren were mentally defective. Public health nurses also intruded into working class family homes to instruct women on the value of "intelligent motherhood."

Before the availability of sulpha drugs (the first antibiotics) in the late 1930s, medical science had few cures for serious aliments, says Heron. And so, understandably, many working people steered clear of doctors, nurses and hospitals until then and relied instead on their own traditional knowledge. Home births were apparently the norm before 1914.

The first decades of the 20th century also witnessed the availability of mass consumer products such as refrigerators, vacuum cleaners and other appliances. But few people in Hamilton could afford them before the prosperity of the post-Second World War period.

These are but a few choice tidbits of Lunch-Bucket Lives, which is ultimately about the complexities of social class-not a subject people talk openly about these days.

This article was first published in the September/October 2015 issue of The Monitor, published by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

By WAHC (anonymous) | Posted September 25, 2015 at 21:49:45

Editor(s): "Workers Historical and Cultural Centre" is in fact called the Workers Arts & Heritage Centre (WAHC). If you could please make the change in the body of this article with a hyperlink to the museum website, it would be greatly appreciated. Thank you.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?