Think about it: tools used for building are depicted on the side of a building that's being destroyed.

By Mark Fenton

Published January 03, 2013

Lomax recorded everything, from the sounds of the junkyard to the sound of a cash register in the market... disappearing machinery that we would no longer be hearing. You know, one thing that doesn't change is the sound of kids getting out of school. Record that in 1921, record that now, it's the same sound.

— Tom Waits (on the field recordings of Alan Lomax)

Alan Lomax is best known for field recordings of bluesmen and folksingers who might otherwise be forgotten. (Robert Johnson is perhaps the most famous example). But I was thrilled to learn that Lomax also archived sounds from industrial America. I hope, similarly, to salvage the beauty of overlooked locations.

Meadowlark School in Edmonton, Alberta looks like countless Canadian schools build after World War II. The tyranny of the unadorned rectangle. The ratio of grass to pavement to building to parking lot. The analogue bell that still rang on Sunday because it predated the finesse of digital programming.

But when I visited it two years ago, the experience couldn't have been replicated by visiting a similar school in Hamilton. Because Meadowlark School isn't a representative elementary school. It's my elementary school. The idea of it not existing any more feels like six years of me not existing any more.

Meadowlark school 2010

It wasn't always the tasteful beige it is now. In the 1970s, turquoise aluminum siding - that I'm not embarrassed to say I miss - adorned that bald face. When I started school it was already dented from top to bottom by a continued assault of basketballs. (No hoops were ever installed to direct our youthful energy. Not urban enough? Too much winter?)

Obscene graffiti was regularly painted on the siding, a flourish that, in my ten-year old judgment, neither added to nor subtracted from the effect of the wall. But I knew that it was bad that people had done this. And I thought it odd that it took the school administration so long to overpaint words that broadcast anger and hate as we frolicked below them.

In hindsight it probably stayed on for less than a week. Child time is different than adult time. A week at age forty is a year at age ten. Most of our life is spent in elementary school.

Unremarkable as Meadowlark School may seem to you, it was vital to my formative years. It was at Meadowlark School that I received regular pummelings by Jeff "Hutch" Hutchins who, in dreams, I still see charging towards me, with that inexplicably ruddy and middle-aged face grafted on a ten-year-old body.

With adult insight I would infer that Hutch was abused at home. That these blows were misplaced. Should he find me and send a friend request to my Facebook page I'll talk him through it.

It was from Meadowlark school that phone-calls home were dispatched by Mrs. Kruger (Or Krueger: I was a slacker at spelling along with everything else) to inform my parents that I never did my math homework. If it wasn't stated I'm sure it was implied that academic neglect at so crucial a learning stage boded ill for Mark. Without rudimentary math, what adult career could he aspire to other than that of unpaid photo essayist?

And above all it was to Meadowlark School that Sherri Anderssen came every day. Sherri Anderssen on whom I had a three-year and unrequited crush (How else could it be? A young lady of Miss Anderssen's calibre would surely set her sights higher than a boy who didn't do his math homework.) I haven't thought of her in decades, and wouldn't have but for the picture above. Such is the power of photography.

But this essay isn't about my school years. It's about the loss of Crestwood School on the Hamilton Mountain. I'd wanted to make record of its wall graphics long before it was slated for destruction. Hearing of its impending doom, I knew I had to move quickly.

I prefer a journey to a mere destination. Consulting my map of Hamilton I found a second school in close proximity to Crestwood. Nothing simpler. I'd walk from Cardinal Heights School to Crestwood School. A nice symmetry. Less than half a kilometre. I packed two power bars and a clementine.

The street was empty. I could park anywhere. This is how door-to-door salesmen of the 20th century must have felt. I wished I'd worn a suit and brought a case of samples. No, not as camouflage, but rather to mess with people's heads by looking like I'd stepped out of a time machine. I'd call people "Sir" and "Ma'am" and use expressions like "fine and dandy," and "the whole kit and kaboodle." Oh, I'd've had a grand old time!

But of course I was only my scruffy 2012 self as I stepped out of the car to be greeted by a figure.

who made me feel like Dante meeting Beatrice. The kind of Greco-Roman statue one associates with graveyards and funeral homes, here reinvented as a birdbath. The emulation of fallen empires, at least in North America, always feels elegiac to me. I might not be journeying back to memories of childhood, but rather, forward to an afterlife. Pouring water out.

A small leap to pouring out the days of our lives, a not much smaller leap to pouring out the centuries of a civilization, leaving only scattered remains. A fitting prologue.

To my surprise, I was, for once, of no interest to workers, parents, or security officers. (I should have begun documenting the Central Mountain years ago! Clearly I look like someone who belongs here. And why shouldn't I? It's a lot like where I grew up!)

I noted small groups of male teens who should be in school at this hour. Taciturn, hunched, inexpressive. Aside from the fact that the mullet and Led Zeppelin t-shirt have gone out of fashion (almost), these boys are indistinguishable from those who wandered through Meadowlark schoolyard in the 1970s and whom I watched in similarly perplexed fascination from the window next to my desk

in Mrs. Krueger's grade four class. (I think I'll stick with that spelling, as the suburban menace her memory summons up when I recall those episodes overlaps nicely with Freddy

Krueger of Elm Street.)

Unfortunately, Mrs. Kreuger did not share my enthusiasm for porous classroom borders. My inattention repeatedly brought the lesson to a halt. "Mr. Fenton!" she would shriek in justified exasperation, as I lurched back to lesson, my open mouth confirming intellectual misattention. "This is clearly old hat to you, since you've moved on to an analysis of the schoolyard. Perhaps you could summarize the topic at hand, for the edification of us all."

Having been tuned to another station for the last several minutes I could no more do this than paraphrase an Einstein lecture at Princeton.

I must, at some point along the winding and overgrown way, have stumbled upon the carcass of Mrs. Kreuger's curriculum, and been inspired finally to butcher, ingurgitate and digest its meat in order to advance further.

By contrast, if I'd neglected my study of the lost youth traversing the schoolyard, I would not have these ruminations ready, in the kaboodle of formative memory, to dish up for this essay.

Mrs. Kreuger, if you aren't staring up at the lid by now - for aren't all teachers, to a Grade Four student, at least 65-years-old - but are alive and surfing the web to discover which of your educational seedlings have matured into proud and lofty maples, please know that I take full responsibility for any deficiencies in this essay. They are not the fault of your teaching.

For once the only surveillance I was under was that of a squirrel. Every time I looked over my shoulder, there it was.

But let's, before the essay is entirely done, get with the program. Cardinal Heights School is still intact and operational. I draw your attention to the iconography of its brickwork.

It's a lot to chew on. The leftmost is the simplest to interpret but also the most jittery to experience in 2012. The tots are being groomed to engineer future cities. Vertical expansion is encouraged. Skyscrapers taller and ganglier with every generation. Fingers of steel and glass fluttering against the heavens, invlunerable to all foes.

The middle icon is more abstract. Thanks to my guide, classical sculpture is on my mind. The stylized wings of Samothrace. Victory to budding brains.

The one on the right is the most perplexing. Its resemblance to a clock at 1:40 or 8:10 doesn't speak to me. Its resemblance to "Blues," probably the most familiar poem by bpNichol, is more telling.

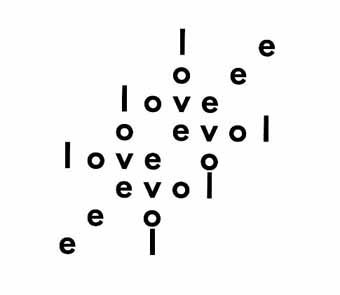

Reduced to an even more abstract graphic. Concrete poetry translated into brick. Yes, schools are the place we nurture our children. But everything is tenuous in these years. There are moments of darkness comparable to any life visits on us. Who has failed to notice that the reverse of the word "love" comes so close to its nemesis.

Note the scream of repeated 'e's through its midst. Downward to the left. In heraldry, this forward-slash on the escutcheon is called a "bend sinister,"

indicating a bastard line.) The 'o's that encase it are mournful or soothing, depending on how you choose to feel it. The 'l's are the solid walls that contain it all. 'V's for victory, and we wish there were more than four of them.

As I move closer to Crestwood School, I recall that there was Crestwood School not far from where I grew up in Edmonton. I used to cut through it to visit a girlfriend in highschool (No, not Sherri Anderssen. Someone entirely else. I had completely fogotten Sherri by then. I'm not even sure how to spell her name, if I ever knew it. More and more I realize this fixation was all about me. She no doubt sensed that. What a relief to be done with that mess.)

If crestwoods roamed the environs of the schoolyard I failed to identify them as such. There is no dictionary definition of the word. "Crest" reveals itself to have several meanings. The tuft atop the head of beast or fowl (or atop a helmet); it can refer to the top of anything (and can be a verb, i.e. reaching the top.) In a coat of arms it's the icon above the escutcheon.

City of Hamilton Coat of Arms

I'm guessing the crest is the maple leaf, though may include the crown. I'm no authority on heraldry. (Nor can I explain why Hamilton's coat of arms lacks a bend, either dexter or sinister.)

All of this is informative, but doesn't exactly explain how "crest" interfaces with "wood." Any help from readers here would be greatly appreciated.

Google finds Crestwood Schools in Medicine Hat, Peterborough and Don Mills and there were more down the list. East of Ontario Crestwood Schools peter out like an Arctic treeline. However, Rosemère, Quebec boasts a Rue Crestwood, and Charlottetown, PEI a Crestwood Drive.

Despite the loss of the Hamilton entry, Canada's crestwoods seem in no more danger of extinction than squirrels. They populate the country from Atlantic to Pacific in a way maple trees never have. In fact, growing up on the prairies I hadn't seen a maple until I came to Ontario - and here I'll nip my maple-leaf-as-a-national-icon rant right in the bud except to say that if I ever discover what crestwoods actually are, I move that they replace the centre panel of our flag.

As for the territories, my suspicion is that above the treeline crestwoods become crestundras. In the simplified graphic style that flags embrace, a mash-up of the two shouldn't be outside the ability of a professional illustrator. I'll do the research if you'll get on the phone to Ottawa.

Here now is what I crested.

And here's what I saw there when I got there.

And do I ever love shooting through chain link. It gives a geometric structure even to chaos. Just as winter trees give structure to a formless sky.

And I didn't notice it 'til I got the pictures home, but there's the squirrel still watching me. Hunched like a gargoyle. Two nubby ears unnaturally far apart, as though wearing a crest of sinister growths.

It was at this point that time and space slipped out from under me. I got back on the road and was thunderstruck by the associations I immediately made with a house on the corner of Bobolink and Meadowlark. (Go close. I'm not making this up.)

The names of the cross streets didn't matter, but the fact that it was a corner property did. That and the era of the house, its ranch style sprawl, the asymmetrical crest of the roof.

All of it took me back to a photo by Stephen Shore, which appears in, Uncommon Places, (Aperture, 1982.)

reproduced from masters-of-photography.com

Stephen Shore was featured in American Topographics a ground-breaking show presented at the Eastman House in Rochester, NY in the mid 70s. All the artists in the show portrayed the ubiquitousness of American industrial sites and suburban sprawl, but Shore was unique among them for printing in colour.

Rather than enhancing his mundane subjects, the colour only accentuated their lack of distinction. (Often, as in the photo above, the play of sun on leaves and nuances of cloud get really interesting next to the blandness of the buildings.) But Shore's apparent ordinariness is sly. His photos possess an almost classical perfection. As in the double vanishing point, or the negative space of the road supplying a geometric structure.

One day, when I was looking at this image I realized that I could make out the names on the street signs: Sutter and Crestline. (Go close. I'm not making this up.) The title of the photo is Fort Worth, Texas. With an intersection and city name...

You guessed it: Google maps.

I'll let you in on an idea I had that I'm sure the occupants of the house, and the editorial staff of RTH, are glad I didn't put into action.

Now that I had a street address, I could send a very polite and formal letter to the current owner(s). Enclosed would be a series of carefully chosen questions.

In this case, a good night's sleep prevented me from following through on my letter. If you live in the house and are reading this, I'd sure like to know what the sign says. I think you'll agree that a quick post in the comments section is a lot less trouble than me flying into Fort Worth and wandering onto your front lawn like a vagrant.

I now understand what recently possessed Bob Dylan to explore the surroundings of Bruce Springsteen's childhood home, provoking the wrath of residents and local authorities (we all have our Mrs. Kruegers). He wanted material that, however vague at the time of his fieldwork, might feed a future project.

I can imagine the questioning he must have gotten from the authorities. I've experienced it many times myself. "Mr. Fenton, could we go over again why you were wandering around on the lawn of a house you have no legitimate connection to, in a city where, by your own admission, you don't know a single person."

"If you'd just go to a computer and google masters-of-photography.com, I think all your questions--"

"Mr. Fenton, in preparing your defence I'm going to recommend a psychiatric assessment."

Replace "Mr. Fenton" with "Mr. Zimmerman." Replace "Masters of Photography" with "Born to Run." It's the same drama.

I like to imagine the crew of the Google Street View truck chatting about how they might shoot this particular location.

Driver 1: You know I'm tempted to swerve and hit the exact spot Stephen Shore placed his tripod.

Driver 2: It would be fun to determine the day of the year and time. Then come back and shoot it exactly then.

Driver 1: Wouldn't it stand out? I mean from the street views around it.

Driver 2: That would be part of the fun. Google Street View users would immediately get the reference and chuckle.

Driver 1: Could we get fired for that?

Driver 2: We could.

(They work in silence for some minutes.)

Driver 1: I'm in.

Driver 2: Let's do it.

Moving closer to Crestwood School I discovered

a deconstruction worker cresting its remains. And just after that I came to the images I want to preserve.

As I write, the tools depicted on these walls are being used to destroy the building they illustrate. Perhaps they'll be saved and integrated into another school, or into the next Board of Education building. Perhaps I'm their Alan Lomax and they'll survive only in these photos.

I can't get as close to them as I'd like to. For my safety a construction fence keeps me at a frustrating remove.

Think about it. Tools used for building are depicted on the side of a building that's being destroyed. How could I fail to think of the Swiss sculptor Jean Tinguely whose 1960 "Homage to New York" was designed to destroy itself at the Museum of Modern Art. And upon which Marcel Duchamp commented

If the saw saws the saw, and if the saw which saws the saw is

the saw which saws the saw, there is a metallic suicide,

Like the cave paintings of Lascaux or Chauvet, or like the visual representations of children, the objects depicted don't relate to a rectangle, or any other shape, that might surround them. The objects are self-contained, free of perspective and meaningful scale in relation to other objects, even those they overlap.

It's a pure, dare I say innocent art.

As Lomax's recording reminds us, it's the timelessness of children entering and leaving a school that makes us regret the passing of any building that housed them.

And then just as my journey reaches its last snapshot, my lyrical nostalgia is shattered.

I'm sure the foreground image is a spray tool. I'm sure its message was benign when the image was created. I don't need to tell anyone what it says to me. Not in the context of a school. Not at the end of 2012. It's still more unfortunately that the triangular spray is dark red.

Artists can't know how the future will qualify their work and I don't think the creator or creators should be judged as irresponsible or insensitive. The resemblance to a handgun wasn't considered when the design went up because no one thought it needed to be.

By Ryvita (anonymous) | Posted January 04, 2013 at 03:38:10

"A photo-essay (or photographic essay) is a set or series of photographs that are intended to tell a story or evoke a series of emotions in the viewer. A photo essay will often show pictures in deep emotional stages. Photo essays range from purely photographic works to photographs with captions or small notes to full text essays with a few or many accompanying photographs."

http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Photo-essay

http://digital-photography-school.com/5-photo-essay-tips

http://inmotion.magnumphotos.com/essays

http://www.foreignpolicy.com/category/section/photo_essay

As interesting as the above essay is, I would love to see an RTH "photo essay" elocuted in compelling and expressive visuals, one that spoke eloquently and with emotional force... An essay whose thrust was articulated almost exclusively in images, with no words other than the briefest of captions and a pithy introduction. Personal preference, admittedly.

By Ryvita (anonymous) | Posted January 04, 2013 at 09:44:20 in reply to Comment 84690

Appreciated. I intended no slight to the author or meant to come across as looking into the gift horse’s mouth. I'm a fan of the blog but I’m not much of a photographer. (Truth be told, less than that.) I just wasn’t sure how RTH define a photo essay rather than a commentary, and that question triggered another. That led me to reflect that the site’s “agenda” seems to get the most traction among the city’s broader IRL population when emotions are brought into play – and, time and time again, logic trumped by emotion. Images (still and video) have an ability to cut through and define issues, for good or bad.

Aimless thoughts, perhaps. The as-is is more than serviceable.

By sad (anonymous) | Posted January 04, 2013 at 11:10:48

Sad. No one will shed a tear for Crestwood, but the larger destruction done to the city will continue.

By Don mills (anonymous) | Posted January 05, 2013 at 21:21:36

Crestwood school in Don Mills is a private school located in the old Brookbanks public school. Brookbanks is the school that sent me to ESL classes ... after we arrived from England...

By jojo (anonymous) | Posted January 06, 2013 at 15:07:52

This is touching and poetic. Confusing and beautiful. Thank you Mr. Fenton!

By Shawn Selway (anonymous) | Posted January 07, 2013 at 00:46:00 in reply to Comment 84696

Bare images are also notoriously ambiguous. You really need to know eg on which side of the barbed wire the people in the photograph are standing, the inside or the outside.

But I agree that it is misleading to call this piece a photo-essay, although not for your reason. Photo essays usually result from a journalistic assignment, while Fenton does both journalism and its reverse at the same time - the reverse being something, well, French, that gets going around 1780 with Rousseau's final effort, Reveries of a Solitary Walker.

Here's a random bit from a page of Nadja (Andre Breton 1928, with 44 images, many of them street scenes in Paris.)

"...almost forbidden world of sudden parallels, petrifying coincidences, and reflexes peculiar to each individual, of harmonies struck as though on the piano...I am concerned with facts of quite unverifiable intrinsic value, but which, by their absolutely unexpected, violently fortuitous character, and the kind of associations of suspect ideas they provoke...I am concerned, I say, with facts which may belong to the order of pure observation, but which on each occasion present all the appearances of a signal, without our being able to say precisely which signal, and of what; facts which when I am alone permit me to enjoy unlikely complicities, which convince me of my error in occasionally presuming I stand at the helm alone... "

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?