I haven't seen "Who the #$&% Is Jackson Pollock?" so I won't comment on that, except to remark that authenticity isn't merely a problem of modernism. A few years ago art historians did a big overhaul of the Rembrandt catalogue, only to discover - or claim - that among many other works the Polish Rider wasn't a Rembrandt, but "school of Rembrandt."

Rembrandt, The Polish Rider

I'm not much of an art historian myself but I gather Rembrandt was an Andy Warhol type. He ran a factory where he got other people to do the work and then put his name on it. (I can hear the interview. Rembrandt: "I haven't done any of my paintings in 1660. Jan and Franz just do them so much better than I do.")

Now The Polish Rider is on my very short list of the greatest art ever made anywhere. It's got it all: an expressive figure posed rakishly atop a horse; the horse ambiguous in execution but redolent of forward momentum creating a nice tension with the figure pivoting away from its trajectory; somber earth tones, yet with light seeming to burst forth from it; and as with any great picture every part of the surface informed by what every other part of the surface is doing.

Knowing that an anonymous painter might have done it does nothing to modify my enjoyment of it, and I promise you that even with border formalities it's worth the 10 hour bus drive to the Frick Collection in NYC to stand before it, not to mention that there's an ass-kicking Vermeer in the same room, and a whole host of masterpieces I don't have time to go into.

My point being that who painted the alleged Jackson Pollock is less important to me than whether the painting is any good. Sounds like a dud Pollock (of which there are many) if no one in the art establishment likes it, and points to a dysfunction in our society, that we care more about the cult of the "master" than the quality of the individual work.

Really, I find it obnoxious that any work of art can trade for $100,000,000 USD whether it's by Pollock, Van Gogh or Rembrandt. In a better world art masterpieces would, without money changing hands, be placed on a public wall for all to see and wealth would be distributed so that everyone could eat, have access to the best health care, and we'd all work at this mess of environmental unsustainability and pointless military invasions we've gotten ourselves into.

In the scheme of things, "The Polish Rider" or "Pollock's No. 1 1950," aren't very important. What makes things still more grotesque with regard to the comodification of art works is that while there's a general consensus that Pollock's art after 1951 (1952 if you're generous) really sucks, and that everyone's five-year-old probably could do better, it's still by Jackson Pollock and by that virtue alone it has to fetch at least seven figures. What offends me isn't the art.

A bad painting just bores me. It's the market response, and the cult of personality that creates it that angers me.

Now, Kevin, that being said, it seems that you have taken a particular struggle against this artist. Let's, for a moment, take the money, which has nothing to do with art, and put it somewhere else. Let's assume no art in the world has a price tag and just talk about it as art.

I neither want nor intend to convert you; and believe me, it's refreshing to hear an honest and passionate reaction against an artist rather than an "oh well I guess it has some, you know, significance I can't see" response.

But I would like to clarify and perhaps even correct a few points in your article that I think may be generalized and sweeping and perhaps not even fair to the facts. I promise I won't resort to the gratuitous and, dare I say, infantile name-calling I found in some of the other responses

Pollock was NOT a naïve painter; he went to art School in Los Angeles and then studied with the well established Thomas Hart Benton, a realist from the Midwest who was once quite a name.

Thomas Hart Benton, People of Chilmark

Pollock's early works were representational and with a clear debt to Benton. He therefore followed the rather conventional road of studying art techniques and then apprenticing with a master (how Renaissance is that!).

I saw an early Pollock once at the Albright Knox museum in Buffalo. It struck me even before looking at the nametag. It was a portrait, and while indeed it seemed somewhat rough in its draughtsmanship it immediately suggested an artist of vision with a sense of a unified surface and in particular a strong sense of the "tactile" nature of his materials.

Photographs are generally useless with regard to abstract artists, where so much depends on scale and surface, but they are particularly so for Pollock's work. I know of no other artist where the "raw fact" of the materials is more important and more powerful.

I won't go through the progression of his art, finding his way through the labyrinth of late cubism and surrealism to a final liberation from the easel painting into an "allover" painting of total abstraction. All this is in those books you referred to and which shelves are bowing under. Again, though, I would clarify a few things.

The term "drip" is a bit inaccurate. Pollock, like many great artists, discovered that the tools of his apprenticeship didn't supply him with the effect he needed. People often have the idea that his method was a reaction to bourgeois convention, a cultivated "half-assed"-ness or, to the more cerebral, an attempt to find "meaning" in "chance" events.

The chance thing was big, particularly with American composers in the Forties. Pollock himself was radically against these views of his technique. The stick gave him the precise mixture of control and resistance that he needed. Or, to be less wordy, it got the paint on the canvas right.

Stan Brakhage, the experimental filmmaker, tells a story of being in Pollock's studio in the late 40s with a bunch of composers who were discussing the use of "chance elements" in their music and how Pollock was doing something similar in painting.

Pollock, not the most articulate man, was getting visibly angry at this talk and finally said: "Do you see that doorknob?"

According to Brakhage the door was between 20 and 30 feet away. He dipped his stick in an open pot of paint, hurled it across the room and it hit smack in the middle of the doorknob and then he said: "That's what I think of chance. Now use it!"

Whether you like the paintings or not, Pollock knew where the paint was going and what it would look like when it got there.

Much has been made of the relation of his technique to Navajo sand-painting, and to some extent he played into it (anything for credibility when you're a struggling artist) but I think the relationship is not just misleading, but the antithesis of what Pollock did.

The natives of the Southwest make pictures by pouring variously coloured sand in patterns, as a form of medicine or healing. It's religious ritual, and the process is everything.

The final product is ultimately not important because as part of the ritual the pictures are destroyed immediately after and the practitioners don't want photos taken of them. (I guess I can see their point, since it's a medical procedure. It would be like if I was going over my cardiogram results with my doctor and a Navajo just walked in and took a picture of it. It would be disconcerting.)

Pollock was a pragmatist and the most secular of artists. What he cared about was the final product, and he'd probably have been much happier if people just looked at the pictures and not his process.

A tradition he felt more affinity with was the oriental brush painters. He was very aware of their use of "action" and the deliberate creation of blots and sprays and blurs. To the end of "feeling" the action of the line. In its most extreme forms, the Japanese Zenga monks achieved an abstract painting centuries before the West. I'm thinking of this famous one by Sengai (1750-1838):

Sengai

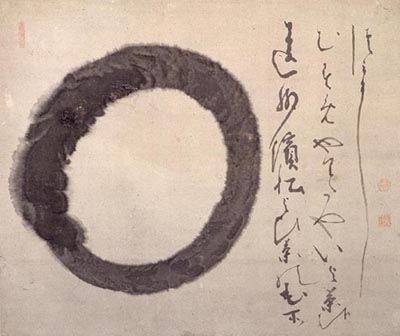

or this even earlier Enso painting by Hakuin Ekaku (1685-1768):

Hakuin Ekaku

Now I'm still a tyro in Zen theory, but I understand that these are spontaneous, willfully unskilled creations, which are made when a monk experiences the desired state of "no-mind." If I understand it correctly, in "no-mind" mental activity stops being a feedback loop of consciousness - the mind thinking of itself thinking and the state most of us can never escape - and they experience the "oneness" of everything, their "Buddha" nature.

And ZAP! they put ink on a canvas and there it is.

Now, I'm an Anglo-Protestant from Regina and I will admit that when I see these things I experience a certain cultural dizziness: "Whoa. I'm not sure I'm ready for this! In order to 'get' this I'm going to have to shed a whole host of preconceptions about art and being and my brain might just implode! Give me something I understand! Something safe! Something that represents the world I know...saaaaaay... Jackson Pollock?"

My point is that abstraction is difficult; and that I have limits too, ones I'm willing to acknowledge. I think abstraction is a tough game not just for the viewer, but for the artist. Pollock hit the wall with it, as did many of his contemporaries. (To put it backwards, representation and the skills that go into doing it can be a REALLY useful and viewer-friendly crutch and I like pictures of flower-arrangements and Mediterranean landscapes and pretty women just as much as the next guy.)

The idea of "expression of a tortured soul" or "working through the subconscious" is nonsense. Or if it's true it's just as true of Rembrandt or any other artist and should be taken for granted. For that matter, the "no-mind" of the great Zenga painters may be nonsense too.

I suspect the good ones - not that I'm in ANY way equipped to judge - are simply good because they've gazed intently at the tradition and learned how to make better pictures (Oboy I hope I don't ruffle any Zen Monk feathers here!).

Pollock was into something larger than he understood. Before Pollock there was good or even great American art, but it had always leaned on European painting. Pollock took painting off the easel and onto the floor, dispensed with centre, narrative, symbolism, illustration. Gave it scale, texture, action, with, at its best, a shamelessly gorgeous blend of colour created within the mesh of lines.

The best Pollocks are classical in their use of colour. The colour comes from nature and natural relations of light and colour. The great Pollocks aren't tough, they're beautiful. When they go bad in the 50s it's partly because of the garish play of non-colours, like oversaturated blues and oranges.

Pollock paved the way for the great abstract painters of his generation: Motherwell, Frankenthaller etc.; and then the mural sized post-painterly abstractionists of the next generation: Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski.

This large-scale all-overness may be deeply American. The spread, the lack of centre, the speed, the "waste" of material, makes sense to have come out of the middle of the American century, the golden age of fossil fuels, the period of vast and ubiquitous urban development - things which have mutated in the nightmare of planless urban sprawl we're dealing with today.

It's no surprise we sometimes bristle now against these honking-big all-over paintings. But they were an honest and prescient picture of his world. Pollock had four years of great paintings, followed by a fairly inactive period of drunkenness and abysmally bad paintings.

He wouldn't be the first revolutionary artist like this. Wordsworth between the ages of 20 and 27 toppled every convention of English poetry and produced masterpiece after masterpiece, only to write doggerel for the remaining five decades of his life.

I make no apologies for Pollock's lifestyle, or for drunk driving. Alas if we pulled all the artists of questionable moral courage from our museums we'd be looking at a lot of bare wall (which isn't to say that artistic and moral greatness are mutually exclusive sets).

To be honest I can't think of a much duller personality than Pollock to read or watch a biography of. The only saving grace of the dreary Ed Norris film was the awesome, if irrelevant, Tom Waits song behind the end credits which I rolled back and played two more times cause I wanted to get something for the price of the rental.

I'd like to end on a high note, and, Kevin, here's my challenge. Drive (better yet, go by public transport) to the National Gallery of Canada (If you end up not enjoying this I'm sure you'll find lots of other cool stuff to do in Ottawa) and go to the room where they keep the Pollock, the one he painted on glass for the Hans Namuth film.

It's a cabinet-sized picture, not excessive in its forces, understated. It's mostly white, and the lines are few. I can follow them with my eye and he's dropped just enough wire and bits of stuff to slow my eye down and intensify the surface. It's all about proportion. (Once again, you can't see this in a photograph.)

Eventually the whole picture begins to float in space and suddenly I don't ever want to look at anything else. I'm tempted to call it the best abstract picture I've ever seen. They I turn to look at Newman's Voice of Fire, and that huge Rothko and note how dead they are in comparison. Nicely proportioned, but those bodies of colour just lie there. (Newman and Rothko both painted great pictures but these aren't them.)

I turn back to the Pollock. It's almost the last good picture he painted. I can talk to death about how the history of Western art led to this point, but I can't explain why it affects me so much, so I'm not likely to convert non-believers. And why the hell would I want to? If I do, I'll just have to line up behind 50 people to get my turn the next time I go.

But have a look.

By An_artist_who_knows_more_art_history_tha (anonymous) | Posted February 28, 2008 at 06:37:33

Pollock never painted a good painting in his life. He was not a naive painter, as you say, but he was a talentless one. He trained under Thomas Hart Benton, but the work from that period shows that he was not able to fully master Benton's technique. In my opinion, anyone having such training who is unable to master such a simple, stylized technique has to be profoundly talentless, and is quite probably of below average intelligence. He explored expressionism, and his morose and permanently angry personality comes out in the ugly, gloomy paintings, along with his total inability to draw. He explored cubism and non-veristic surrealism -- methods of painting that require no artistic talent, and was as good or bad at such painting as anyone else. The abstract expressionist paintings express nothing at all. They follow the method of "automatic painting", which, according to the dogma of the time (based on erroneous psychological theories), release the subconscious and reveal deep sentiments. Actually, they are just pure, empty scribbles, and like all scribbles, completely meaningless.

It is an article of faith that Pollock is a genius and that his paintings express profound sentiments or ideas. There is not one shred of evidence to support this belief, and a mountain of evidence to contradict it. Pollock never said or did a single thing in his life that showed the spark of genius -- in any area of life, never mind art, but he did a great deal to show that he was an inarticulate, drunken, irascible, irresponsible, narcissistic, morose lout. He also was inconsiderate enough to murder the young Edith Metzger for no reason at all.

Pollock-worship is a faith-based religion.

Oh, by the way, this thing about old masters like Rembrandt letting pupils do all their work for them and taking all the credit is nonsense. Unlike the Andy Warhols and Damien Hirsts of today, they had rules; paintings produced in the studio entirely by pupils cost less than paintings made by pupils according to the master's design and with intervention from the master, and these in turn cost less than "autograph" works done mainly or entirely by the master. Furthermore, the pupils were not anyonymous, but upon graduation became masters in their own right, and some of them earned lasting fame.

Rembrandt taught his pupils to imitate his own technique and style very closely, and what with art dealers in the 17th and 18th century selling everything that looked vaguely Rembrandt-like as a "Rembrandt", it is no wonder that there is now uncertainty about some works.

By An_artist_who_knows_more_art_history_tha (anonymous) | Posted February 28, 2008 at 06:46:49

You write:

"Really, I find it obnoxious that any work of art can trade for $100,000,000 USD whether it's by Pollock, Van Gogh or Rembrandt. In a better world art masterpieces would, without money changing hands, be placed on a public wall for all to see and wealth would be distributed so that everyone could eat, have access to the best health care, and we'd all work at this mess of environmental unsustainability and pointless military invasions we've gotten ourselves into."

I beg to differ. The sums spent on paintings do not tie up either money or resources. Indeed, they make money flow more freely. Suppose you own a painting that cost a few hundred dollars to make (parts and labour), but now is worth a few million. This will can be used as security borrow money and invest, so money is freed up by such art that would probably not otherwise be available. Far better that rich people should spend their money on bits of canvas and paper than on things that really waste resources, such as building huge stone pyramids.

By An_artist_who_knows_more_art_history_tha (anonymous) | Posted February 28, 2008 at 07:04:32

The real comparison between Rembrandt and Pollock is this:

The fact that Rembrandt's pupils were able to convincingly imitate his style shows that they were talented. The fact that Pollock was unable to imitate the unable to imitate his own master's style shows that Pollock was untalented.

At one point, you write that a Pollock painting "seemed somewhat rough in its draughtsmanship". Clearly, you are a master of understatement.

By Jim MenaMan (anonymous) | Posted April 23, 2009 at 15:02:15

well said you made a few good points dont worry about the other people's comments they must have nothing better to do.

By Pierre (anonymous) | Posted August 25, 2009 at 20:56:44

I don't like Pollock's art. It was just a splatter of paints in the canvass. No meaning at all. I believe that the style of the skillfull artists should meaningful and hard to imitate by an ordinary person. A three year old child can do Pollock's style with both eyes close.

By Humiltonian (anonymous) | Posted October 27, 2009 at 19:58:50

Rembrandt was a great artist, with obvious talent. Pollock was a mediocre marketing figure, bolstered by Mr.Greenberg of New York. He was the flavour of the day.

By toadvine (anonymous) | Posted May 12, 2010 at 15:32:17

I think that some people miss the fact that in the generation that Pollock was in, artist, when they became working artist, were not trying to be the next Rembrandt, or the next Monet, or the next whoever. They were not working day in and day out at copying someone elses work excactly. Why would they? Copying a Rembrandt is pointless. They were trying to carve out new territory. I think that Pollock succeeded wonderfully. It triumph is creating a work that is not possible to exactly recreate, and it is pointless to try.

By 1 (anonymous) | Posted July 08, 2010 at 07:43:51

oh goodness. pollock worship usurped by "old master" worship. you do realize rembrandt used garbage materials, storebought preprimed linen with the cheaper of the two lead whites available at the time...loaded with chalk mind you...along with orpiment, realger, azurite and vermilion? all with his bituminous and smalt ridden backgrounds which have darkened so much 40% of his work is gone in some cases. do not speak the name rembrandt in the same breath and Vermeer. in comparison, rembrandt had only a rudimentary understanding of materials and his paintings suffered greatly. that pollock could not or did copy or "do" benton means less than nothing.

By 12 (anonymous) | Posted July 21, 2013 at 15:15:58

Art shouldn't be sold, but should instead be free to all?

Are you proposing that the tax payers pay the artists?

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?