In 1969 a funk band called The Winstons recorded an instrumental b-side titled "Amen Brother." In the middle of it, their drummer, Gregory Cylveser "G.C." Coleman played a four bar drum solo now known as the Amen Break. (I'm not a drummer so I'm just going to have to trust wikipedia on the following notation.)

If, like me, you find drum patterns more compelling to the ear than the eye, I assure you it's not hard to find the break on youtube. Over the past 44 years it has been sampled in R & B and hip hop, and then sampled from the samples, ad infinitum. (The backbeat of N.W.A.'s "Straight Outa Compton" is a notable example.)

Calculating its number of appearances in recorded music has, for some time, been impossible. Such appropriation is hardly uncommon in popular music - this is, after all, the age of cutting and pasting - but what about examples in other media?

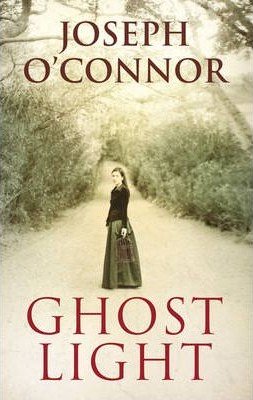

Last week I was in Chapters and came upon a book entitled Ghost Light. Having seen the cover image before, I wanted to investigate its provenance.

The jacket credits attributed it to Lorainne Molina, but that particular Lorainne Molina didn't appear to have web presence. I did, however, find a site by Sarah Johnson, called "Reading the Past," in which she isolates several appearances of the same image.

She sources it as "Woman with a Birdcage in a Lane" courtesy of Getty images.

(This is as good a place as any to note that in all versions - even the hardbound of Ghost Light that I held in my hand - the WBL is poorly focused. This could be a reproduction problem: in any media sampling, increased layers of reproduction create a decreased integrity to the original. On the other hand, the photo itself could have been poorly focused, suggesting a chance, unposed capture.)

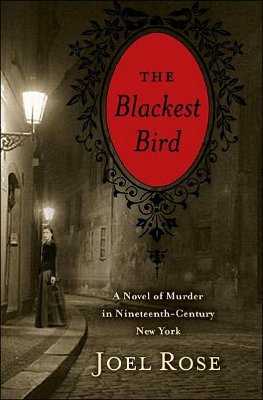

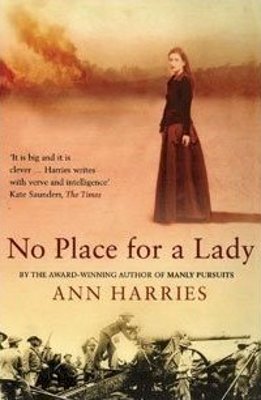

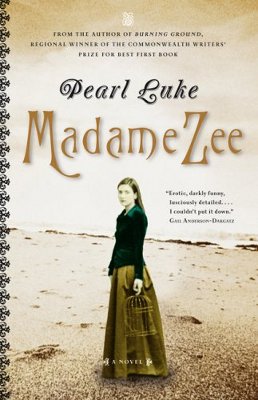

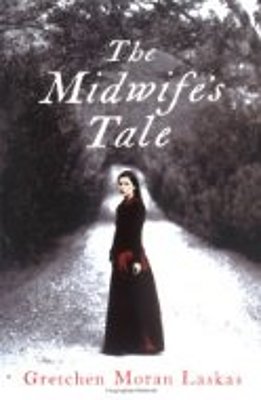

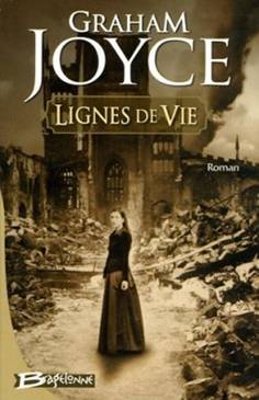

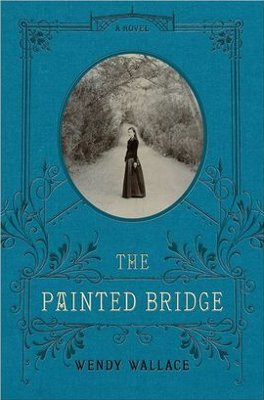

I subsequently found a few appearances of WBL on my own

though none of the above where what triggered my memory when I saw Ghost Light in Chapters.

I'm not well read in fantasy, but when I was an undergraduate, a friend in my program (now a published fantasy writer) said that the one essential fantasy novel of our time was a book called Little, Big by John Crowley.

The copy he loaned me was one of those chunky '80s mass market paperbacks with shiny embossed lettering on the cover, the obligatory ten pages of raving review quotes, a wide-eyed and euphoric author photo, and text on that grey pulp paper that always smells like newsprint.

I think I read 20 pages of its dense prose, dismissed it as pretentious, and handed it back to him.

I was wrong. What little I'd read stayed with me, making me wish I'd read it through.

So I was thrilled when I came upon it five years ago, reissued by Harper Perennial, and with a blurb by Harold Bloom describing it as "the most enchanting twentieth-century book I know." Subsequently I've heard Bloom compare it favourably to the Alice books.

Enchanting is the word for it. A novel that effortlessly mixes magic with a penetrating exploration of adult relationships and modern politics: a great book without a tradition outside itself.

I do, however, disagree with Bloom in calling it a successor to Alice in Wonderland. What it does resemble is Sylvie and Bruno, Lewis Carroll's neglected two-volume monster of a children's book.

Sylvie and Bruno doesn't compare to Alice. It's sprawling and full of Victorian sentimentality and little momentum. But it has an appealing sunniness, and it's full Carroll's usual ruminations on contemporary physics, math and semantics.

It also features one of Carroll's most demented nonsense poems, stanzas of which appear at regular intervals throughout and serve as a running gag which morphs itself like a virus through the book's several hundred pages.

In fact, if anything gives this monstrosity a structure, it's these verses. Here's an example of two stanzas, all of which follow the "He thought he saw..." "He looked again..." template:

He thought he saw an Elephant

That practised on a fife:

He looked again, and found it was

A letter from his wife.

'At length I realize,' he said,

'The bitterness of Life!'

[...]

He thought he saw a Buffalo

Upon the chimney-piece:

He looked again, and found it was

His Sister's Husband's Niece.

'Unless you leave this house,' he said,

'I'll send for the Police!'

The whole book is best enjoyed with the original illustrations, which feel like they should decorate an antique candy box. Cranking up sublimated Victorian Eros to the expected pitch.

It's insipid and gooey and one of those books I enjoy but would never recommend. I'm just putting it out there.

Little Big makes repeated reference to Sylvie and Bruno, but balances its fairytale quality with an eclectic intricacy reminiscent of Thomas Pynchon. The book's charm is all in the detail. Here's a delicious moment where the lead characters are exchanging love letters:

"I found an old pile of newspapers," said her letter which crossed his (the two truckdrivers waving to each other from their tall blue cabs on the misty morning turnpike).

Yes, I know this capsule review wanders far from the subject at hand. In defense of relevance, all I can say is how happy I am that the promiscuous WBL briefly found as worthy a partner as Little, Big.

Why is WBL so irresistible to book marketing? I assume the publisher pays Getty Images for use and I have a feeling that Getty images buys the photos outright - i.e. that photographer and model have received as much royalty money as G.C. Coleman did for the Amen Break: $0.00.

It's easy to peg WBL as a knockoff of the great Victorian photographer Julia Margaret Cameron.

right down to the sepia and the pose, but as soon as you start to compare the two, you realize just how modern WBL is. The snug - way too revealing - fit of the jacket. The very 20 C body ideal. Hair that's far too straight and undecorated by ribbons or scarves (I challenge you to find a Victorian photo of a woman without 'stuff' in her hair, or else a whole lot of 'wave.')

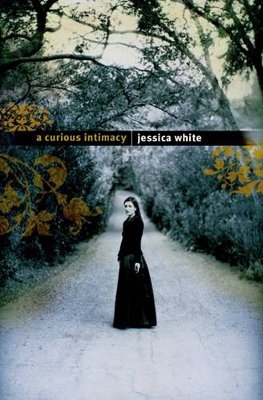

As with the Amen Break, the sample is usually altered. I haven't found the original photo, but I suspect A Curioius Intimacy (above) is closest unaltered image.

She's on a lane retreating to a single vanishing point that snakes at the summit. The foliage curling up and around is almost too good a sexual metaphor (the kind that George Eliot's writing is full of, as close to explicit as late 19th century writers were allowed) which is probably why most designers crop it down.

And what are we to make of the birdcage? If you see the cage as an allegory, you'll get a feminist "women imprisoned by the Victorian patriarchy," reading.

If you see the cage as an accessory, it's much more complex. There's no bird in it, so why has she brought it outside? Did she just give a bird its freedom, or is she about to capture one? Now the cage is empowering. And indeed, her stance and gaze are strong. It's the dueling pose, Sideways from the opponent. Reducing the body's target potential.

That both possibilities exist is a nice dualism for the complex power dynamic in any romance or - dare I say - any master and servant relationship. (Just wait 'til WBL decorates historical erotica: Fifty Shades of Sepia).

Of course, in some versions the cage is photoshopped out. She's just there. Pasted into any landscape she's amazingly self-contained.

And who is the model? How old is she now? Was she even aware? "I just know that's me. I still have the outfit. It was in Vermont. My stepfather's estate. I was out capturing goldfinches when I heard someone approach. I turned just as a trembling, elfin woman snapped her Leica. I pursued her, but like a startled fawn she disappeared into foliage, never to reappear."

No wonder people get upset when I photograph them from the shadows. They're being cheated. If not out of a fortune, then at least out of a modeling credit.

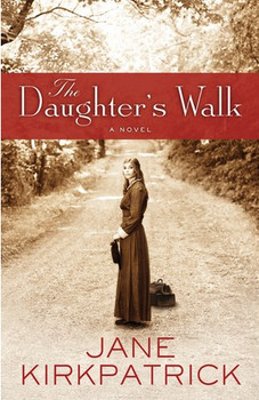

The day after filing this article I came upon the following image. The photo is credited to Jim Celuch.

Knockoff or homage? You decide. Compared to her older sister, she's relaxed and unthreatening. For menace and ambiguity, a hat and travel bag can hardly compare to a cage, and while the stance is almost identical to WBL you'd never describe this as a dueling pose.

The execution is flawless; my guess is that the figure is crisper than WBL was even in the first printing (I'm holding a copy of the book in my hand and I can almost make out where pupil meets iris).

Like a tribute band that play tighter than originals, because, after all, the originals were inventing, not refining.

By night flight (anonymous) | Posted January 24, 2013 at 00:08:37

The figure in the road seems to be taking one last look back, at the person or place she is leaving behind. What is at the end of that road? Compare with the Gothic romance covers of the seventies, similarly a lone female figure, a young woman approaching or fleeing some Great House of confusing experience, under turbulent skies...

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?