On June 21, I published an article on induced demand, the tendency for new road construction to generate additional traffic by itself. Research over the past 20 years has found strong support for induced demand and generated traffic. However, today's industry standard traffic modeling systems are not designed to account for induced demand. The result is misleading projections that over-estimate the benefits of new road construction.

An RTH reader just sent in a link to the March 2012 issue of the European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research (EJTIR), which includes an essay titled Traffic Forecasts Ignoring Induced Demand: a Shaky Fundament for Cost-Benefit Analyses.

The authors note that induced demand "is now widely accepted among transport researchers" but is "still often neglected in transport modeling." To demonstrate this, they model a proposed road project in Copenhagen with and without short-term induced demand. The authors find:

Even though the model calculations included only a part of the induced traffic, the difference in cost-benefit results compared to the model excluding all induced traffic was substantial. The results show lower travel time savings, more adverse environmental impacts and a considerably lower benefit-cost ratio when induced traffic is partly accounted for than when it is ignored.

According to the paper, additional traffic capacity influences six parameters that affect traffic volumes. The first two parameters merely re-allocate existing volumes, whereas the latter four actually generate a net increase in total traffic:

When traffic modeling ignores induced demand, the benefits of road expansion are exaggerated and the negative effects are downplayed. This biased cost-benefit analysis leads policymakers to over-allocate public capital toward road expansion at the expense of more effective and sustainable infrastructure investments.

As the example shows, this systematic problem with how the transportation engineering field projects traffic is not restricted to North American planners. However, a few European countries, like Norway, began to incorporate induced demand into their modeling processes after the late 1990s.

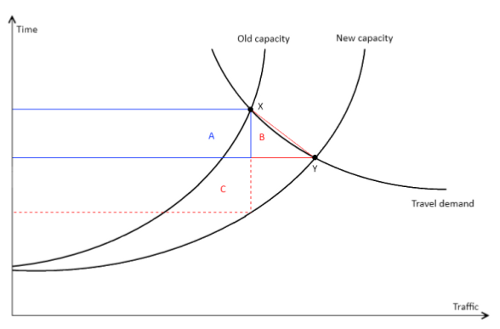

Example of supply and demand curves and time-benefit calculations for a road before and after capacity increase (image from linked paper)

The authors examine the Nordhavnsvej project, a planned road expansion in Copenhagen designed as "congestion relief" so traffic can bypass an adjacent neighbourhood that is expected to expand by 80,000 people and jobs in a new urban development.

Comparing a traffic projection that incorporates short-term induced demand with a projection that does not include it, the authors observe, "a small amount of induced traffic can have a disproportionately large effect on the cost effectiveness of a road project."

In short, the additional traffic induced by the new lane capacity consumes all of the newly available capacity so that travel times improve much less than projected. In some case, as German mathematician Dietrich Braess observed, additional lane capacity can actually make travel times worse.

If an expensive public capital project to increase lane capacity merely draws more people into cars in the short term and encourages more car-dependent land use in the longer term, we need to step back and ask what we're really trying to accomplish - especially when the same money spent improving walking/cycling/transit options would instead draw people out of their cars and into those modes.

By LOL (registered) | Posted July 10, 2012 at 19:30:00

with so many of us commuting such long distances, in this country, walking cycling and transit will always take a back seat to driving. I know you do not like that fact but it is a fact.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?