Investments and policies that create more multi-modal transportation systems can provide significant economic benefits, particularly over the long run.

By Todd Litman

Published February 11, 2009

(First published on February 9, 2009 by the Victoria Transport Policy Institute. Reprinted with permission.)

This report discusses factors to consider when evaluating transportation economic stimulation strategies.

Transportation investments can have large long-term economic, social and environmental impacts. Expanding urban highways tends to stimulate motor vehicle travel and sprawl, exacerbating future transport problems and threatening future economic productivity. Improving alternative modes (walking and cycling conditions, and public transit service quality) tends to reduce total motor vehicle traffic and associated costs, providing additional long-term economic savings and benefits.

Increasing transport system efficiency tends to create far more jobs than those created directly by infrastructure investments. Domestic automobile industry subsidies are ineffective at stimulating employment or economic development. Public policies intended to support domestic automobile sales could be economically harmful in the long-term.

Economic stimulation refers to policies and investments that increase employment and business activity. Some stimulation strategies are better than others overall because they help achieve additional strategic goals. This is particularly true of transportation investments, which have large leverage effects.

For example, one federal dollar may attract five state and local matching dollars, which leverages fifty private investment dollars, which influences hundreds of consumer expenditure dollars, causing thousands of dollars in long-term economic, social and environmental benefits and costs.

Table 1 illustrates the impacts of different types of transportation investments. Walking, cycling and public transit investments help create communities where residents own fewer vehicles, drive less, and rely more on alternative modes, providing various benefits.

| Highway-Expansion | Multi-modal Improvements | |

|---|---|---|

| Investments | Spending focuses on urban highway expansion. | Spending focuses on road maintenance, and on walking, cycling and public transit improvements. |

| Land Use Impacts | More new development at automobile-dependent locations along highways. | More new development occurs within existing urban areas or new transit-oriented suburbs. |

| Transport Impacts |

|

|

| Economic Impacts |

|

|

Infrastructure investments have long-term impacts that affect future travel activity and costs.

For this analysis it is useful to distinguish between roadway rehabilitation and expansion projects. There is little controversy concerning the value of basic roadway rehabilitation, sometimes called fix it first (NGA, 2004) or asset management ("Asset Management," VTPI, 2008).

However, there is growing debate over the value of urban highway expansion (new road links, additional traffic lanes, expanded intersections, etc.) because they tend to induce additional vehicle travel and stimulate more dispersed, automobile-oriented land use development (sprawl).

Much of this debate reflects differences in the scope of analysis (Litman, 2009a). Highway expansion advocates tend to focus on traffic congestion reduction objectives and ignore the negative effects of induced vehicle travel and sprawl.

(Induced travel refers to additional vehicle travel that results from expansion of congested highways. For more information see Generated Traffic: Implications for Transport Planning [PDF]. Sprawl refers to dispersed, automobile-dependent, urban fringe land use development. For more information see Evaluating Transportation Land Use Impacts [PDF].)

Advocates of investments in alternative modes tend to consider a wider range of impacts and objectives, including traffic congestion reduction, parking cost savings, consumer cost savings, accident reductions, improved mobility for non-drivers, energy conservation, pollution reductions, and public fitness and health.

This report investigates these issues and describes specific factors to consider when evaluating such investments. It describes various trends that are changing future travel demands, evaluates the long-term economic impacts of various transport policies and programs, and identifies best practices for selecting economic stimulation investments. It evaluates arguments by highway expansion advocates that highway investments are better overall than investments in alternative modes.

Table 2 indicates various industries' direct regional economic impacts ranked from highest to lowest direct employment generation.

| Industry | Total Jobs Per $ million Final Demand | Total Employment Per Direct Job | Total Output Per $ Final Demand | Total Labor Income Per $ Final Demand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Production | 37.19 | 1.593 | 2.41 | 0.77 |

| Nursing and Residential Care | 36.43 | 1.461 | 2.21 | 0.95 |

| Administrative Support | 33.11 | 1.534 | 2.17 | 0.98 |

| Food and Drinking Services | 32.12 | 1.451 | 2.13 | 0.71 |

| Arts and Recreation | 30.87 | 1.479 | 2.01 | 0.75 |

| Educational Services | 27.13 | 1.550 | 2.07 | 0.71 |

| Legal /Accounting services | 24.37 | 1.995 | 2.24 | 1.07 |

| Other Transport/Postal Offices | 23.04 | 2.031 | 2.26 | 0.94 |

| Architectural and Engineering | 22.96 | 2.234 | 2.26 | 1.10 |

| Ambulatory Health Care | 22.88 | 2.012 | 2.16 | 0.99 |

| Crop Production | 22.74 | 2.033 | 2.30 | 0.64 |

| Waste Management | 21.99 | 1.773 | 2.04 | 0.65 |

| Retail | 21.92 | 1.623 | 1.89 | 0.66 |

| Truck Transportation | 21.57 | 2.165 | 2.20 | 0.83 |

| Transport/Warehousing/Storage | 21.49 | 2.341 | 2.24 | 0.95 |

| Hospitals | 20.38 | 2.108 | 2.11 | 0.86 |

| Ship and Boat Building | 19.97 | 2.428 | 2.20 | 1.06 |

| Mining | 19.37 | 2.320 | 2.23 | 0.80 |

| Furniture | 18.90 | 2.005 | 2.05 | 0.68 |

| Printing | 18.22 | 2.061 | 2.02 | 0.73 |

| Fishing, Hunting, and Trapping | 17.99 | 2.085 | 2.05 | 0.78 |

| Textiles and Apparel | 17.53 | 1.782 | 1.82 | 0.60 |

| Forestry and Logging | 17.30 | 1.845 | 1.82 | 0.37 |

| Construction | 15.95 | 2.344 | 1.97 | 0.64 |

| Fabricated Metals | 15.01 | 2.101 | 1.85 | 0.61 |

| Other Information | 14.96 | 3.359 | 2.17 | 0.68 |

| Wood Product Manufacturing | 14.78 | 3.052 | 2.16 | 0.54 |

| Real Estate, Rental and Leasing | 14.65 | 1.765 | 1.70 | 0.43 |

| Other Finance and Insurance | 14.43 | 2.918 | 2.10 | 0.69 |

| Other Manufacturing | 14.28 | 2.034 | 1.81 | 0.57 |

| Food, Beverage and Tobacco | 14.18 | 4.001 | 2.17 | 0.51 |

| Machinery Manufacturing | 13.86 | 2.229 | 1.83 | 0.61 |

| Wholesale | 13.76 | 2.298 | 1.80 | 0.62 |

| Nonmetallic Mineral Products | 12.56 | 2.555 | 1.88 | 0.52 |

| Primary Metals | 12.34 | 2.782 | 1.90 | 0.57 |

| Credit Intermediation | 12.34 | 2.735 | 1.93 | 0.51 |

| Computer and Electronics | 11.42 | 2.762 | 1.79 | 0.58 |

| Other Utilities | 11.05 | 2.193 | 1.64 | 0.47 |

| Internet Service Providers | 10.76 | 5.887 | 1.89 | 0.67 |

| Telecommunications | 10.71 | 4.006 | 2.00 | 0.50 |

| Water Transportation | 10.60 | 3.682 | 1.80 | 0.48 |

| Paper Manufacturing | 10.54 | 4.053 | 1.99 | 0.51 |

| Electrical Equipment | 10.50 | 2.436 | 1.69 | 0.48 |

| Other Transportation | 9.93 | 3.727 | 1.82 | 0.45 |

| Air Transportation | 9.60 | 2.811 | 1.72 | 0.44 |

| Chemical Manufacturing | 7.96 | 6.408 | 1.78 | 0.50 |

| Electric Utilities | 5.84 | 4.221 | 1.73 | 0.30 |

| Aircraft and Parts | 5.63 | 2.814 | 1.38 | 0.32 |

| Gas Utilities | 5.57 | 5.382 | 1.48 | 0.26 |

| Petroleum and Coal Products | 3.23 | 9.555 | 1.35 | 0.15 |

This table indicates various industries' regional economic impacts. Construction rates average.

The construction industry ranks about average, creating approximately 16 regional jobs per million dollars spent, which is better than some goods, but ess than labor-intensive services such as nursing care (36.43), arts and recreation (30.87) and education (27.13).

The values in Table 2 are Washington State impacts; national economic impacts are higher since some inputs are imported from other states. Table 3 indicates the national economic impacts of highway expenditure. These have declined during the last decade due to improved labor productivity and increased imports of inputs such as fuel, aggregate and steel. These are upper-bound estimates because they assume resources (workers, equipment and materials) would otherwise be unused; in many cases highway construction competes for resources with other projects, so actual employment and business activity gains are smaller than indicated in Table 3.

| 1997 | 2005 | 2007 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Construction Oriented Employment Income | $589,363 | $428,842 | $394,814 |

| Construction Oriented Employment Person-Years | 15.6 | 10.0 | 9.5 |

| Supporting Industries Employment Income | $222,577 | $192,752 | $175,068 |

| Supporting Industries Employment Person-years | 5.5 | 4.5 | 4.3 |

| Induced Employment Income | $545,182,399 | $548,154,399 | $492,090,698 |

| Induced Employment Person-years | 17.0 | 14.7 | 14 |

| Total Employment Income | $1,357,125 | $1,169,751 | $1,061,973 |

| Total Person-years | 37.9 | 29.2 | 27.8 |

This table indicates total estimated economic impacts from a million dollar highway expenditure. These impacts are declining due to increased productivity and reliance on imported resources.

Transit facility investments have similar economic impacts (STPP, 2004). Transit vehicle purchases tend to have smaller economic impacts because they are mostly imported, although this could change if U.S. transit vehicle manufactures became more competitive. Highway and transit maintenance, and transit operations, are all relatively labor intensive, creating large numbers of jobs per dollar spent.

Automobile use is also labor-intensive but consists of unpaid driving that creates no paid jobs. Travel by alternative modes is often more productive since transit passengers can work or rest, and pedestrians and cyclists get exercise that would otherwise require special time.

Overall, transportation infrastructure investments are not particularly effective short-term economic stimulation expenditures. If the only objective is economic stimulation it would be better to invest in more labor-intensive industries such as medical services, education and public transportation operation. Transportation facility investments are only justified if they reflect strategic objectives and future demands.

Transportation demand refers to the amount and type of travel people choose given specific prices and service options. Highway advocates justify highway expansion based on claims that automobile travel demand is large and growing while demand for other modes is small and declining (Moore and Staley, 2008). These claims are not completely true.

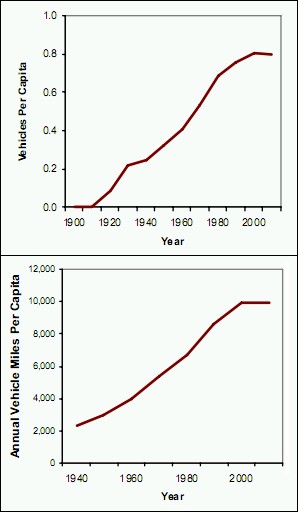

Motor vehicle ownership and use grew steadily during the last century, as illustrated in Figure 1. However, this growth stopped about the year 2000 and has since declined slightly, while transit ridership is growing (Puentes, 2008).

Per Capita vehicle ownership and use grew during the Twentieth Century but has saturated and is expected to decline in the future due to demographic and economic trends.

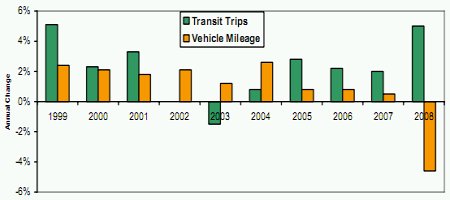

Transit travel increased more than automobile travel during seven of the last ten years and each of the last four years, as illustrated in Figure 2. During this period transit travel grew 24% compared with a 10% VMT increase. Many transit systems now carry maximum peak period capacity, constraining further growth. Increasing capacity and improving service quality would allow transit ridership growth.

Transit trips increased more than vehicle mileage during seven of the last ten years.

Much of this transit ridership growth predated the 2008 fuel price spike. It reflects demographic and economic trends shifting travel demands (Litman, 2006; Puentes, 2008):

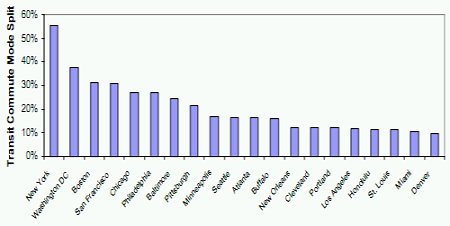

Although public transit serves only about 2% of total U.S. trips, it serves a much larger portion of urban travel, as illustrated in Figure 3. Transit share is even higher for travel to large commercial centers, and so has relatively large economic importance.

A relatively large portion of urban-peak travel is by public transit.

Transit critics claim that consumers always prefer automobile travel and abandon alternative modes as they become wealthier, but there are many indicators that wealthy people will choose alternative modes if they are convenient, comfortable and affordable ("Success Stories," VTPI, 2008).

Transit ridership has increased significantly in U.S. cities that improved their public transit systems (Henry and Litman, 2006).

Similarly, there is growing demand for housing in more accessible, multi-modal communities (Molinaro, 2003; Reconnecting America, 2004). The 2004 American Community Survey found that consumers place a high value on urban amenities such as shorter commute time and neighborhood walkability: 60% of prospective homebuyers surveyed reported that they prefer a neighborhood that offered a shorter commute, sidewalks and amenities like local shops, restaurants, libraries, schools and public transport over a more automobile-dependent community with larger lots but longer commutes and poorer walking conditions (Belden, Russonello and Stewart, 2004).

Described differently, high levels of automobile travel result, in part, from market distortions such as low road user fees and fuel taxes, abundant and unpriced parking, and automobile-oriented transport and land use planning ("Market Principles," VTPI, 2008).

These distortions make consumers rich in mobility but poor in other ways. For example, low road user fees increase general tax burdens (about a third of U.S. roadway expenditures are financed though general taxes), cheap driving exacerbates traffic congestion and accident problems, low fuel taxes increase pollution emissions, and parking subsidies increase taxes and housing costs.

Table 4 lists various market reforms required to increase transport system efficiency. They would reduce urban highway travel demand and increase demand for alternative modes. Until these reforms are fully implemented, expanding congested roadways is economically harmful overall because it exacerbates problems such as congestion, crashes and pollution emissions.

| Efficient Pricing | Typical Additional Charge Per Urban Vehicle-Mile | Typical Vehicle Travel Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Cost recovery road pricing | 2-5 cents | 2-10% |

| Cost recovery parking pricing | 5-10 cents | 10-20% |

| Distance-based insurance and registration fees | 5-10 cents | 5-15% |

| Congestion fees | 0-20 cents | 5-10% |

| Pollution emission fees | 2-5 cents | 2-10% |

| Totals | 14-50 cents | 20-50% |

This table illustrates efficient urban motor vehicle fees and their likely travel impacts. This suggests that in an efficient transport system, consumers would choose to drive less, rely more on alternative modes, and be better off overall as a result. For more detailed analysis see Socially Optimal Transport Prices and Markets

To their credit, some highway advocates support tolling of added capacity to recover costs and control congestion, but this only addresses two of the external costs of induced travel. Only if all the pricing reforms described above are fully implemented can roadway expansion be justified and efficient.

Efficient pricing and smart investments would not eliminate automobile travel demand, but this analysis indicates that at the margin (relative to current travel patterns) many Americans would prefer to drive less and rely more on alternative modes if they had more efficient pricing, and alternative modes were more convenient, comfortable and affordable.

This demand for high quality transport alternatives is likely to increase in future decades due to previously described demographic and economic trends. As a result, investments that improve the quality of user modes respond better to future demands than urban highway expansion.

There is considerable debate concerning the relative merits of different transportation modes. As previously mentioned, there is little debate concerning the value of basic highway rehabilitation, and much of the U.S. highway system is now due for major maintenance and repair, as indicated in Federal Highway Administration Conditions and Performance Reports (FHWA, 2006).

Table 5 summarizes results of that report, indicating that current annual highway and transit investments are approximately $28 billion below what is needed for basic maintenance and operational improvements, without highway expansion. It makes little sense to expand the highway system if current funding is inadequate for required maintenance of existing supply.

| 2004 Capital Outlays | Cost to Maintain | Percent Difference | Cost to Improve | Percent Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highways | $26.0 | $31.9 | 23.0% | $48.6 | 87.1% |

| Bridges | $10.5 | $8.7 | -16.6% | $12.4 | 18.6% |

| Transit Systems | $12.6 | $15.8 | 25.4% | $16.4 | 30.2% |

| Total | $49.1 | $56.4 | 15% | $77.4 | 58% |

Substantial additional investments are needed to maintain and improve existing U.S. highways and bridges, even without system expansion.

Table 6 compares the highway expansion and public transit improvement benefits. Both provide economic stimulation and congestion reductions (although highway expansion generally only provides temporary congestion reduction benefits), but transit improvements provide several other benefits, including improved convenience and comfort to current transit travelers, parking and consumer cost savings, improved mobility for non-drivers, and various environmental and social benefits.

| Benefits | Roadway Expansion | Transit Improvements |

|---|---|---|

| Short-term economic stimulation | X | X |

| Long-term job creation | X | |

| Congestion reduction | X | X |

| User convenience and comfort | X | |

| Parking cost savings | X | |

| Consumer cost savings | X | |

| Reduced traffic accidents | X | |

| Improved mobility options | X | |

| Energy conservation | X | |

| Pollution reduction | X | |

| Physical fitness & health | X | |

| Land use objectives | X |

Public transit improvements provide a wider range of benefits than highway expansion.

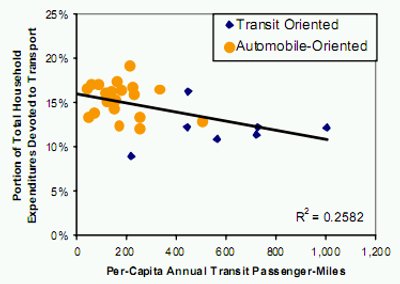

The portion of total household budgets devoted to transport (automobiles and transit) tend to decline with increased transit ridership, and is lower on average in transit oriented cities.

For example, adding an urban highway lane typically accommodates about 2,000 additional daily vehicle trips. (Most traffic lanes carry far more total daily trips, but these are the additional trips that can occur because peak-period traffic is less congested.)

Although this reduces congestion on that roadway (at least temporarily, until generated traffic fills the capacity), it often increases "downstream" congestion by increasing surface street traffic, increases parking demand, requires travelers to own and operate automobiles, and to the degree it induces more total vehicle travel it increases accidents, energy consumption, and pollution, all costs that tend to be reduced if the same trips are made by alternative modes.

Highway expansion tends to stimulate sprawl while transit improvements encourage more compact and multi-modal "transit oriented" development. Residents of multi-modal communities tend to spend less on transportation overall, as illustrated in Figure 4, savings $1,000 to $3,000 annually per household in transport expenditures and so have more money to spend on other goods ("Affordability," VTPI, 2008).

In addition, governments and businesses have lower roadway and parking costs. Table 7 summarizes external costs of increased vehicle traffic and sprawl, costs that tend to be reduced with improvements to alternative modes.

| External Costs Of Motor Vehicle Traffic | External Costs of Urban Sprawl |

|---|---|

|

|

Increased vehicle traffic and sprawl impose various external costs (costs imposed on other people).

Critics sometimes point out that public transit has higher average government subsidies per passenger-mile than automobile travel, but this is an unfair comparison ("Transit Evaluation," VTPI, 2009). About half of transit subsidies are provided for the sake of basic mobility (transit service at times and locations with low demand, and special services for people with disabilities such as paratransit and wheelchair lifts), which tend to have high costs per passenger-mile.

Transit operates on major urban corridors where the total costs (roads, parking and externalities) of accommodating more automobile traffic is also high. In addition, automobile travel receives significant non-government subsidies such as free parking. When properly evaluated, public transit is often more cost effective and requires less total subsidy than accommodating additional automobile travel on the same corridors ("Transit Evaluation," VTPI, 2009).

Advocates argue that highway expansion is a cost effective economic development strategy by reducing business production costs, particularly congestion (Moore and Staley, 2008), but actual benefits are often smaller than proponents claim (Litman, 2009a). Roadway supply experiences declining marginal benefits: building the first paved highway to a region usually provides significant economic benefits, but each additional unit of capacity provides less net benefits (SACTRA, 1999; Kopp, 2006).

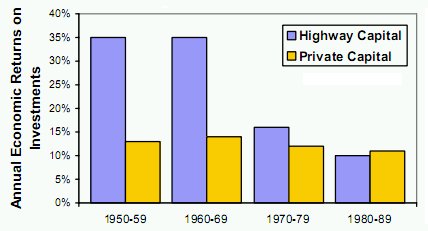

Although highways showed high economic returns during the 1950s and 60s, this declined significantly by the 1990s and has probably continued to decline since the most cost effective projects have already been implemented, as indicated in Figure 5.

Highway investment economic returns were high during the 1950s and 60s when the U.S. Interstate was first developed, but have since declined, and are now probably below the returns on private capital, suggesting that highway expansion is generally a poor investment of scarce public resources.

Conventional project evaluation tends to exaggerate highway expansion economic benefits by ignoring induced travel effects (Hodge, Weisbrod and Hart, 2003; Litman, 2007a). Most highway expansion benefits are captured by consumers; it increases their mobility, allowing motorists to live in more distant suburbs and exurban areas.

Only a small portion of these benefits are captured by producers, since commercial vehicles represent only a small portion of total traffic. Although some industrial trends, such as just-in-time production, increase the importance of road transport, other trends, such as telecommunications that substitute for physical travel, reduce its importance.

More efficient management of existing highways, such as congestion pricing, can provide greater economic benefits by allowing higher-value trips (such as freight deliveries and business travel) to outbid lower value trips (such as SOV commuting) for scarce road space.

Conventional project evaluation also tends to undervalue public transportation service quality improvement benefits (Litman, 2007b). High quality, grade separated public transit attracts people who would otherwise drive on congested roadways, which reduces the point of congestion equilibrium (the level of congestion at which travelers reduce their peak-period trips).

Although congestion never disappears, it is not nearly as bad as would occur without such transit services. Since transit services experience economies of scale, service quality and cost effectiveness tend to increase as demand grows, providing additional user benefits.

After analyzing highway investments impacts on local economic activity, Peterson and Jessup (2007) conclude, "some transportation infrastructure investments have some effect on some economic indicators in some locations." O'Fallon (2003) recommends these infrastructure investments to maximize productivity:

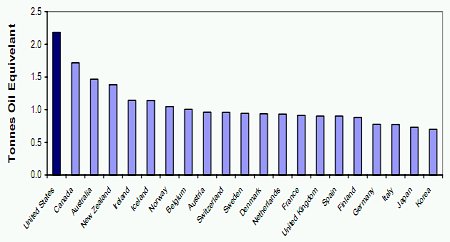

Transportation planning decisions significantly affect future economic development by influencing energy consumption, particularly oil imports. North Americans currently consume about twice as much transportation fuel per capita as peer countries, due largely to differences in fuel taxes, transportation investments and land use planning.

Had North America implemented energy conservation policies comparable to peer countries two decades ago, national fuel consumption would be about half its current rate, keeping hundreds of billions of dollars in the economy annually.

Americans consume about twice as much transportation energy per capita as peer countries due to differences in transportation policies, including planning practices and fuel prices.

Dependency on imported petroleum is economically harmful. A US Department of Energy study estimated that excessive dependence on imported petroleum cost the U.S. economy $150-$250 billion in 2005, at a time when oil averaged $35-$45/bbl (Greene and Sanjana Ahmad, 2005).

A U.S. Department of Energy study estimates the external costs of imported oil (described as "a measure of the quantifiable per-barrel economic costs that the U.S. could avoid by a small-to-moderate reduction in oil imports") to be $13.60 per barrel, with a range of $6.70 to $23.25 (Leiby, 2007). These estimates omit military costs.

These costs are expected to increase in the future as international oil prices rise and as U.S. oil production declines.

For this study we commissioned special analysis using the IMPLAN model, based on 2006 U.S. economic conditions (Lindall and Olson, 2005). Table 8 summarizes results. This indicates that in 2006, each million dollars shifted from fuel expenditures to a typical bundle of consumer goods adds 4.5 jobs to the U.S. economy (17.3-12.8), and each million shifted from general motor vehicle expenditures (purchase of vehicles, servicing, insurance, etc.) adds about 3.6 jobs (17.3-13.7).

Public transit expenditures create a particularly large number of jobs since it is labor intensive.

For data see the OECD Country Data Summary Spreadsheet.

| Expense category | Value Added 2006 Dollars |

Employment FTEs* |

Compensation 2006 Dollars |

|---|---|---|---|

| Auto fuel | $1,139,110 | 12.8 | $516,438 |

| Other vehicle expenses | $1,088,845 | 13.7 | $600,082 |

| Household bundles | |||

| - Including auto expenses | $1,278,440 | 17.0 | $625,533 |

| - Redistributed auto expenses | $1,292,362 | 17.3 | $627,465 |

| Public transit | $1,815,823 | 31.3 | $1,591,993 |

This table summarizes input-output table analysis. In 2006, a million dollars shifted from fuel expenditures to a typical bundle of consumer goods adds 4.5 jobs to the U.S. economy, and each million shifted from general motor vehicle expenditures adds about 3.6 jobs. (* FTE = Full-Time Equivalent employees)

These impacts are likely to increase in the future as international oil prices rise, U.S. oil production declines, and petroleum and vehicle production become more automated.

Although exact impacts are uncertain and impossible to predict with precision, between 2010 and 2020 a million dollars shifted from fuel to general consumer expenditures is likely to generate at least six jobs, and after 2020 at least eight jobs.

This indicates that reductions in automobile ownership and use, and shifts from driving to alternative modes support economic development. Current planning decisions can support future economic development by encouraging transportation system efficiency.

For example, transport policies and investments that halve U.S. per capita fuel consumption would save consumers $300-500 billion annual dollars, provide comparable indirect economic benefits, and generate 3 to 5 million domestic jobs.

Consider three policy scenarios.

The first, favored by the domestic vehicle industry, maintains the current 34 mile-per-gallon (MPG) average new vehicle fuel economy target for 2020, which increases 2020 fleet economy to 28 MPG. This requires technical improvements, allowing continued production and sales of large numbers of SUVs, light trucks and performance cars.

The second scenario raises the 2020 fuel economy target to 50 MPG, increasing average fleet efficiency to 38 MPG. This requires vehicle size reductions so the U.S. vehicle fleet becomes similar to those in Europe and Asia.

The third option includes this fuel economy target plus mobility management policies such as road and parking pricing, higher fuel taxes, and distance-based insurance and registration fees, more investment in alternative modes, and smart growth policies to reduce total vehicle ownership 10% and average annual vehicle travel from 12,000 to 10,000 miles per vehicle by 2020.

The results are summarized in Table 9.

This suggests that transportation policies have large economic impacts by affecting consumer expenditures, particularly per capita fuel consumption. Policies that encourage fuel conservation and increase transport system efficiency tend to increase economic productivity, competitiveness and employment, creating far more jobs over the long run than most industry stimulation strategies.

| Scenario | Scenario 1: Auto-industry favored policies | Scenario 2: Increased vehicle fuel economy | Scenario 3: Increased transport system efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Practical requirements | Technical innovations | Technical innovations and smaller vehicles | Technical innovations, smaller vehicles, and mobility management. |

| Vehicle Population (millions) | 260 | 260 | 234 |

| New vehicle average MPG | 35 | 50 | 50 |

| Fleet average MPG | 28 | 38 | 38 |

| Avg. annual miles per vehicle | 12,000 | 12,000 | 10,000 |

| Avg. annual gallons per vehicle | 429 | 316 | 263 |

| Fuel expenses per vehicle | $2,143 | $1,579 | $1,316 |

| Fuel savings per vehicle | $0 | $564 | $827 |

| Percent fuel savings | 0% | 26% | 39% |

| Total fuel expenditures (millions) | $557,143 | $410,526 | $342,105 |

| Consumer fuel savings | $0 | $146,617 | $215,038 |

| Economic costs at $27.20/barrel (millions) | $72,163 | $53,173 | $44,311 |

| U.S. economic benefits (millions) | $0 | $18,990 | $27,852 |

| Domestic jobs created | - | 1,172,932 | 1,720,301 |

| Non-fuel expenses per vehicle | $3,031 | $3,031 | $2,728 |

| Total savings per vehicle | $0 | $564 | $1,130 |

| Percent total consumer savings | 0% | 11% | 22% |

| Total vehicle expenditures (millions) | $788,060 | $788,060 | $638,329 |

| Consumer vehicle savings | $0 | $0 | $149,731 |

| Domestic jobs created | - | - | 598,926 |

| Total jobs created | - | 1,172,932 | 2,319,226 |

| Other economic benefits | - |

|

|

This table compares the economic impacts of various transport policies and investments. Scenario 1 is the baseline. It assumes $5 per gallon fuel prices, 8 net jobs created per million dollars in fuel cost savings and 4 net jobs per million dollars in non-fuel vehicle cost savings.

These scenarios are feasible. Several commercially available vehicles now exceed 50 mpg and their performance (load capacity, acceleration, amenities, etc.) is improving with new technologies. Achieving a 50 MPG average would require a vehicle fleet similar to those in wealthy European countries.

Mileage reductions of 20-40% are also feasible using economically justified policies, such as more efficient road and parking pricing, increased investment in alternative modes, and smart growth land use policies (VTPI, 2008).

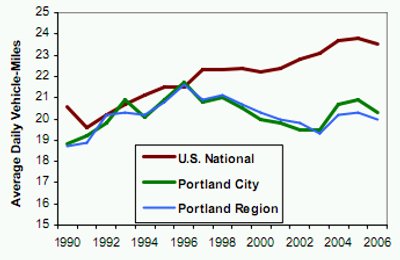

The result would be communities similar to Davis, Eugene, Sacramento and Portland, where per capita motor vehicle travel is significantly lower than the national average (less than 20 daily vehicle miles per capita) due to investments in alternative modes and supportive transportation and land use policies (Figure 7).

Average daily per capita vehicle travel varies significantly between different cities due to differences in transportation and land use policies. Cities with lower vehicle travel have invested in alternative modes and implemented supportive transport and land use policies.

A good example is Portland, Oregon, which demonstrates that rational transport and land use policies can reduce per capita vehicle travel in established cities, as illustrated in Figure 8. By shifting investments from urban highway expansion to high quality transit systems and non-motorized facilities, and implementing supportive land use policies that encourage more compact development, the city reduced per capita vehicle travel about 20% compared with national trends over a ten-year period.

This has provided a variety of economic, social and environmental benefits (Cortright, 2007).

Portland vehicle travel declined 10-15% due to transport and land use policy changes.

Domestic vehicle manufactures were once leaders in profits, employment and innovation, but now have low profits and average wages, and depend on government subsidies. GM, Ford and Chrysler currently have about 240,000 employees, less than 0.2% of the U.S. workforce, and are contracting. Industry advocates exaggerate the damages that would result from auto company bankruptcies by including all related jobs (CAR, 2008).

Without domestic manufactures Americans would continue to purchase, service and produce vehicles (many foreign manufactures have US factories), and many affected employees would find other jobs or are soon scheduled to retire. This is not to deny that auto company bankruptcies would harm many employees and investors, but there is little reason to favor this industry over others with better futures.

The $34 billion vehicle industry loans represent about $150,000 per job, the approximate cost of a four-year private university education. Although these are loans, which may be repaid, current economic trends do not favor domestic vehicle production so full repayment is unlikely. These loans are in addition to numerous direct and indirect incentives, subsidies and favorable tax policies by local, state and federal governments. Automobile industry subsidies appear to be an inefficient economic stimulation strategy.

Even worse, efforts to support domestic vehicle producers could distort public policies economically, socially and environmentally harmful ways. Large, fuel inefficient vehicles are the U.S. manufactures most profitable products. If U.S. citizens and public officials consider themselves vehicle industry shareholders, they may favor policies that favor inefficient vehicles and encourage automobile ownership.

This has already occurred: in December 2008 the federal government stopped proposed increases in vehicle fuel efficiency standards on grounds that they threaten domestic manufacturers' competitiveness and profitability. Even worse would be transport policies favoring automobile travel over more efficient alternatives to support the automobile industry.

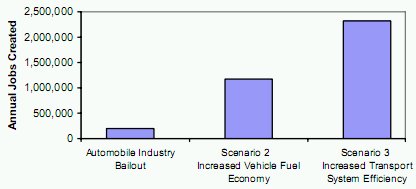

Figure 9 compares domestic jobs created by various policies. Automobile industry loans create a fraction of the domestic jobs created by previously described scenarios that increase fuel economy and transport system efficiency. This understates Scenario 3 benefits since improved transport system efficiency increases economic development in other ways, including reduced congestion, accidents and parking costs.

Increased transport efficiency creates far more jobs than automobile industry loan guarantees.

Below are additional factors to consider when evaluating transportation investments.

Improving transportation and land use options tends to increase consumer welfare by allowing individuals to choose the combination that best meet their needs. For example, some people prefer walking or cycling, others prefer driving, and others prefer transit travel. Investments and policies that improve these options tend to benefit consumers by letting them choose the options that best reflect their needs and preferences.

The current U.S. transportation system offers relatively good automobile travel options: it is possible to drive from nearly any origin to almost any destination with reasonable convenience and comfort (although travel may be slow under congested conditions), but travel without an automobile is often difficult.

As a result, improving walking, cycling and public transit, and providing more housing options in multi-modal communities, tends to increase consumer welfare by allowing individuals to choose options that match their needs and preferences.

Improving affordable transportation options, such as walking, cycling and public transit, tends to be particularly beneficial for lower-income people ("Affordability," VTPI, 2008). This further increases consumer welfare, helps achieve equity objectives, and helps solve specific problems, such as the difficulty some economically disadvantaged people have accessing education, employment and basic services.

A common criticism of smart growth and transit oriented development is that it increases housing costs, displacing lower-income residents (called gentrification). This is not necessarily true. Although urban areas tend to have high land unit costs (costs per acre) and many people want to live in accessible, transit-oriented areas, good public policies can offset these factors by increasing densities (reducing the amount of land required per housing unit), increasing the total amount of transit oriented development and incorporating affordable housing into such projects in order to reduce the price premium charged for accessible locations.

In other words, housing is only unaffordable in transit oriented locations because demand exceeds supply, so the best solution is to expand supply. Since residents of multi-modal communities spend significantly less on transportation, such locations can be more affordable overall (transport and housing costs combined) even if housing costs are somewhat higher.

A more diverse transportation system tends to provide additional economic efficiency benefits because it is more flexible and able to respond to future changes, including sudden and unexpected changes that may result from a disaster or economic crisis. For example, a more diverse transportation system is less vulnerable to closure of a network link, a fuel shortage, or the need to evacuate.

Smart transportation economic stimulation reflects the following principles:

This suggests that the following investments are best:

Many types of public investments can stimulate short-term employment and economic activity but some are better overall because they also support other strategic goals. Smart economic stimulation responds to future demands and helps achieve various economic, social and environmental objectives. Federal investment priorities and rules can influence long-term transport system and community development patterns, and therefore people's opportunities, costs, lifestyles and risks for generations in the future.

This study indicates that highway rehabilitation and safety programs are economically beneficial, but urban highway expansion tends to stimulate more driving and sprawl, exacerbating transportation problems. Demographic and economic trends reduce highway expansion benefits and increase demand for high quality alternatives. Investments that improve alternative modes tend to provide greater total benefits, including the following:

Increasing transport system efficiency is particularly important for long-term economic development. Vehicle and fuel purchases generate fewer domestic jobs and less economic activity than most other consumer expenditures. Each million dollar shifted from purchasing fuel to a typical bundle of consumer goods adds 4.5 U.S. jobs, and this is likely to increase significantly in the long run as international oil prices rise and domestic production declines.

Each million shifted from general motor vehicle expenditures (purchase of vehicles, servicing, insurance, etc.) adds about 3.6 U.S. jobs. Public transit operations create a particularly large number of jobs.

A reasonable scenario of aggressive fuel economy targets, investments in alternative modes and supportive land use policies can reduce U.S. fuel consumption 20-40%, saving future consumers $150-350 billion annually in fuel and vehicle expenses, providing economic benefits from reduced fuel import costs of similar magnitude, producing additional economic, social and environmental benefits, and generating 1 to 2 million additional annual domestic jobs.

This equals the total jobs created by $30 to $60 billion in infrastructure expenditures and is five to ten times greater than the jobs provided by domestic vehicle manufactures.

Financial support of U.S. automobile manufactures is not economically justified. The subsidy required to maintain an automobile factory job is greater than the cost of a typical college education or could finance significant public school education improvements. Investments in efficient transportation modes or improved education create more total jobs per dollar and better prepare the economy for future demands.

APTA (2003), Public Transportation Gets Our Economy Moving (www.apta.com); at www.apta.com/research/info/online/facts_economic_09.cfm.

ASTRA (www.iww.uni-karlsruhe.de/astra/summary.html), is a set of integrated transportation and land use models that predict the long-term economic and environmental impacts of different transportation and land use policies in Europe.

Belden, Russonello and Stewart (2004) American Community Survey, National Association of Realtors (www.realtor.org) and Smart Growth America (www.smartgrowthamerica.org).

BLS (2003), Consumer Expenditure Survey, Bureau of Labor Statistics (www.bls.gov).

CAR (2008), CAR Research Memorandum: The Impact on the U.S. Economy of a Major Contraction of the Detroit Three Automakers, Center for Automotive Research (www.cargroup.org/documents/FINALDetroitThreeContractionImpact_3__001.pdf).

Census Bureau (2002), American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau (www.census.gov).

Robert Cervero (2003b), "Road Expansion, Urban Growth, and Induced Travel: A Path Analysis," Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol. 69, No. 2 (www.planning.org), Spring 2003, pp. 145-163.

Harry Chmelynski (2008), National Economic Impacts per $1 Million Household Expenditures (2006); Spreadsheet Based On IMPLAN Input-Output Model, Jack Faucett Associates (www.jfaucett.com).

Joe Cortright (2007), Portland's Green Dividend, CEOs for Cities (www.ceosforcities.org); at www.ceosforcities.org/internal/files/PGD%20FINAL.pdf.

David Goldstein (2007), Saving Energy, Growing Jobs: How Environmental Protection Promotes Economic Growth, Profitability, Innovation, and Competition, Bay Tree Publishers (www.baytreepublish.com); summary at www.cee1.org/resrc/news/07-02nl/09D_goldstein.html.

FHWA (various years), Highway Statistics Annual Report, Federal Highway Administration (www.fhwa.dot.gov/policy/ohpi/hss).

FHWA (2006), Status of the Nation's Highways, Bridges, and Transit: Conditions and Performance Report, Federal Highway Administration (www.fhwa.dot.gov/policy/2006cpr).

FHWA (2008), Employment Impacts of Highway Infrastructure Investment, Federal Highway Administration (www.fhwa.dot.gov); at www.fhwa.dot.gov/policy/otps/pubs/impacts/index.htm.

Good Jobs First (www.goodjobsfirst.org) investigates the economic impacts of Smart Growth and efficient transport, and promotes policies that support employment and equity objectives.

David Greene and Sanjana Ahmad (2005), Costs of U.S. Oil Dependence: 2005 Update, Oak Ridge National Laboratory (http://cta.ornl.gov); at http://cta.ornl.gov/cta/Publications/Reports/ORNL_TM2005_45.pdf.

David T. Hartgen and M. Gregory Fields (2006), Building Roads to Reduce Traffic Congestion in America's Cities: How Much and at What Cost? Reason Foundation (www.reason.org); at www.reason.org/ps346.pdf.

Lyndon Henry and Todd Litman (2006), Evaluating New Start Transit Program Performance: Comparing Rail And Bus, VTPI (www.vtpi.org); at www.vtpi.org/bus_rail.pdf.

Daniel J. Hodge, Glen Weisbrod and Arno Hart (2003), "Do New Highways Attract Business? Case Study For North County, New York" Transportation Research Record 1839, Transportation Research Board (www.trb.org), pp. 150-158.

Andreas Kopp (2006), Macroeconomic Productivity Effects of Road Investment: A Reassessment for Western Europe, 06-2210, Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting (www.trb.org).

Paul N. Leiby (2007), Estimating the Energy Security Benefits of Reduced U.S. Oil Imports, Oak Ridge National Laboratory (www.ornl.gov).

Scott A. Lindall and Douglas C. Olson (2005), The IMPLAN Input-Output System, MIG Incorporated (www.implan.com).

Todd Litman (2001), "Generated Traffic; Implications for Transport Planning," ITE Journal, Vol. 71, No. 4, Institute of Transportation Engineers (www.ite.org), April, 2001, pp. 38-47; also available at Victoria Transport Policy Institute website (www.vtpi.org/gentraf.pdf).

Todd Litman (2006), "Changing Travel Demand: Implications for Transport Planning," ITE Journal, Vol. 76, No. 9, (www.ite.org), September 2006, pp. 27-33; at www.vtpi.org/future.pdf.

Todd Litman (2007a), Smart Transportation Investments: Reevaluating The Role Of Highway Expansion For Improving Urban Transportation, Victoria Transport Policy Institute (www.vtpi.org); at www.vtpi.org/cong_relief.pdf.

Todd Litman (2007b), Smart Transportation Investments II: Reevaluating The Role Of Public Transit For Improving Urban Transportation, Victoria Transport Policy Institute (www.vtpi.org); at www.vtpi.org/cong_reliefII.pdf.

Todd Litman (2009a), Transportation Cost and Benefit Analysis Guidebook, Victoria Transport Policy Institute (www.vtpi.org); at www.vtpi.org/tca.

Todd Litman (2009b), Evaluating Transportation Economic Development Impacts: Understanding How Transportation Policies and Planning Decisions Affect Productivity, Employment, Business Activity, Property Values and Tax Revenues, Victoria Transport Policy Institute (www.vtpi.org); at www.vtpi.org/econ_dev.pdf.

Joseph Molinaro (2003), Higher Density, Mixed-Use, Walkable Neighborhoods - Do Interested Customers Exist? National Association Of Realtors (www.realtor.org).

Adrian Moore and Sam Staley (2008), All Infrastructure Spending Is Not Created Equally: Randomly Pouring Billions Of Dollars Into Roads Won't Fix America's Gridlocked Transportation System, Reason Foundation (www.reason.com); at www.reason.com/news/show/130444.html.

M.I. Nadri and T.P. Mamuneas (1996), Contribution of Highway Capital to Industry and National Productivity Growth, FHWA, USDOT.

NGA (2004), Fix it First: Targeting Infrastructure Investments to Improve State Economies and Invigorate Existing Communities, National Governors Association (www.nga.org).

Carolyn O'Fallon (2003), Linkages Between Infrastructure And Economic Growth, New Zealand Ministry of Economic Development (www.med.govt.nz); at www.med.govt.nz/templates/MultipageDocumentTOC____9187.aspx.

OFM (2008), 2002 Washington Input-Output Table, Washington State Office of Fiscal Management; at www.ofm.wa.gov/economy/io/2002/default.asp.

Robert Puentes (2008), The Road…Less Traveled: An Analysis of Vehicle Miles Traveled Trends in the U.S., Brooking Institution (www.brookings.edu).

Reconnecting America (2004), Hidden In Plain Sight: Capturing The Demand For Housing Near Transit, Center for Transit-Oriented Development; Reconnecting America (www.reconnectingamerica.org), for the Federal Transit Administration (www.fta.dot.gov); at www.reconnectingamerica.org/public/download/hipsi.

SACTRA (1999), Transport Investment, Transport Intensity and Economic Growth, Standing Advisory Committee on Trunk Road Assessment, Dept. of Environment, Transport and Regions (www.roads.detr.gov.uk); summary report at www.dft.gov.uk/stellent/groups/dft_transstrat/documents/pdf/dft_transstrat_pdf_504935.pdf.

Robert Shapiro, Nam Pham and Arun Malik (2008), Addressing Climate Change Without Impairing the U.S. Economy: The Economics and Environmental Science of Combining a Carbon-Based Tax and Tax Relief, The U.S. Climate Task Force (www.climatetaskforce.org); at www.climatetaskforce.org/pdf/CTF_CarbonTax_Earth_Spgs.pdf.

SP (2009), Building a Green Economic Stimulus Package for Canada, Sustainable Prosperity (www.sustainableprosperity.ca).

STPP (2004), Setting the Record Straight: Transit, Fixing Roads and Bridges Offer Greatest Job Gain, Surface Transportation Policy Project (www.transact.org); at www.transact.org/library/decoder/jobs_decoder.pdf.

VTPI (2008), Online TDM Encyclopedia, Victoria Transport Policy Institute (www.vtpi.org).

By LL (registered) - website | Posted February 17, 2009 at 13:29:15

"Although highways showed high economic returns during the 1950s and 60s, this declined significantly by the 1990s and has probably continued to decline since the most cost effective projects have already been implemented, as indicated in Figure 5."

I think there was some serious Jerry Lee Lewis and Elvis being played in council chambers when they decided to make Red Hill Extortionway happen.

I found the stats about Portland interesting. Note that they their Vehicle Miles Travelled (VMT) per capita was one of the lowest, while their proportion of transit usage was not all that spectacular. A lot of people are still driving there, but they don't have to go as far. It goes to show that sensible land use and balanced transportation policy isn't about punishing the driver. It's about providing freedom of choice for all.

By Mr. Meister (anonymous) | Posted February 22, 2009 at 03:13:07

Wow. Sure hope you wrote that for some other purpose than RTH. I do not have the time to thoroughly read the whole thing let alone have the kind of time it took to write that. Most of what I skimmed through had a very familiar ring to it. The big problem for transit in most Canadian and American cities is population density. Compared to most European cities ours are much lower density. If you look at the actual numbers the difference is quite staggering. Where the density (and overall size) really climb up there, we actually have decent transit just look at Toronto or New York. The other factor you do not address is the price of homes. Buying the typical single family home with the white picket fence so many of us want and have is virtually impossible in most of Europe for the vast majority of the population. This lifestyle is the leading contributing factor to the whole urban sprawl "problem". As long as we encourage or even tolerate this lifestyle we will have all of the same problems. Do you want to be the one to tell the people they cannot have that house with the white picket fence. I sure do not.

I know 6 families who have moved from Toronto to Hamilton for this single reason. In 4 at least 1 of the them still commutes to Toronto and they hate every second of it. Why? because they want that single family house and are willing to pay for it in so many ways.

Personally I would love to not have a car and all the expenses that go with it but it just is not feasible. The city is to spread out. Take a bus during rush hour and they are full and standing room only. Take that same bus in the evening and the wait is extensive because the few buses that are running are practically empty.

Things are changing slowly very very slowly. How much further can people commute?

By Undustrial (registered) - website | Posted February 25, 2009 at 21:53:18

I know a whole bunch of people who've moved from Toronto to Hamilton, and transit was frequently a part of those choices - you can easily get to a job in Downtown Toronto from Downtown Hamilton in much less time than you can from many suburban areas of Toronto. I know people who've cut 40 or more minutes off their commute by such methods. The bus isn't as cheap, but for what you save renting a nice house in Durand vs. a bachelor apartment in Toronto, it's pretty worth it.

That seems to me a failure of Toronto transit in some way, at least to the outer reaches of town.

By wondering (anonymous) | Posted February 26, 2009 at 00:19:35

sounds like you dont do the commute at least not in prime time

I've done it and never again

By JonC (registered) | Posted March 02, 2009 at 22:08:24

I did the commute for about 5 years, the train, the bus and carpooling. It ends up being about an hour each way, which was to those on the outskirts or Toronto. I wasn't a big fan of getting up early, but having a couple hours dedicated to reading everyday was alright.

By schmadrian (registered) | Posted March 04, 2009 at 06:58:22

In the end, beyond the environment, beyond the cost...is the ugly truth that the automobile is at the heart of the North American value system. And migrating people away from that, as I've often said, requires one of two things: either a crisis...or something 'sexier'. I won't belabour the point here, but it's vital to understand and appreciate how deeply embedded this attachment is to the car...especially when you consider that it is, essentially, a means to get from Point A to Point B (NOT an indicator of achievement or status), an evolution of the horse.

I don't own a car. But I am a driver, have been for 30+ years. Most of my trips are on foot...or by bus. This means I spend a lot of time observing. And as much as I'd love to see an entirely different paradigm exist, our world, our cities, our neighbourhoods have been designed around the automobile. When you combine this with the materialistic attachment (that is, to consumerism, as opposed to the experiential), you have a near-intractable situation. So much so that I'd place a ton of money on this bet: most people I see on the HSR, if they had the resources, would be driving to where they're going, not taking the bus.

Just as the answer to our obesity problem is not just a matter of getting people to eat less, or the answer to our crime problem is not just a matter of having more police, more jails, the solution to this conundrum isn't just a matter of making bus frequency or transit reliability better. Its solution lies in changing the value system itself. To wit: until the car is not the prime indicator of self-esteem, we're screwed. (And I need to point out that if we were suddenly able to produce Individual Transportation Vehicles that were no drain on the environment at all, or at least of the most negligible sort imaginable, we would be in no better state. But most people cannot fathom this paradigm shift...it's beyond their ken.)

By Robert D (anonymous) | Posted March 04, 2009 at 22:18:21

Shcmadrian, I don't think I've ever read a comment I agreed with more, anywhere!

Although I will say this, you are not alone in being an someone who can drive, but chooses to walk or take public transit instead. I do the same.

By LL (registered) - website | Posted March 05, 2009 at 00:20:59

Where are all the anti-valley politicians and their apologists? Here is a solid, well-sourced article that flatly refutes ALL the arguments that plowing a sprawl highway through a nature park is a great idea. Do you folks even read?

schmadrian: I'm totally with you on finding deeper root causes to the mass motoring problem. But I reject the notion that "car culture" is just an aggregate of individual preferences, or that a lack of intelligence is what's driving it.

One historical factor in mass motoring that nobody on this site seems to talk about is Fordism - the ruling class strategy of bottling class conflict through relatively higher wages and mass (I would argue compulsory) consumption.

The ruling class abandoned Fordism a long time ago, and have been chipping away at real wages for years, even though they continue to push the mass consumption part (hence the debt problem). One could easily see this crisis as a final cataclysm in that era of capitalism.

Can mass motoring really continue under these conditions? How long do you think it'll be before working people start to create car shares, ride bikes, etc. in lage numbers? I have a hunch that forced car dependence is one of their weakest links.

In short, anti-car propaganda has to work as an aspect of a greater popular struggle, not just an environmentalist lecture. You want sexy? Emphasize that a collective abandonment of the costs of car dependence could result in a shorter work week. Celebrate the freedom and individuality of the bicycle.

Sure the car industry is one of the biggest spenders on ad propaganda. But they're looking pretty foul right now. It's times like this that activists need to shine. Don't throw up your hands in despair.

By LL (registered) - website | Posted March 05, 2009 at 00:45:56

That reminds me of something. Europe has pretty well developed car-based subcultures - arguably even more so than here. Yet mass motoring there is far less grotesque in its profusion.

By Undustrail (anonymous) | Posted March 05, 2009 at 17:40:48

Part of the problem here is that cars are a lot more than a means of getting from A to B. Car culture is everywhere - TV, movies, the Fortinos parking lot(a genuine mecca of car fanatics some nights), college road trips and old-time war movies. That car was the holy grail of high-school dating, your apartment for 2 months when you lost your job and now stands proudly to demonstrate that you are, by far, the coolest of your co-workers.

Walking and bussing just don't have that kind of cultural significance...you don't go for a cruise for fun on a Sunday afternoon on the 5E Deleware, and you can't sit for hours with the guys at work talking about shoe mechanics.

What's the alternative to this? Bike culture.

Once you stand out as a cyclist, you have friends everywhere...the guy manning the cash register will rant about his stolen bike, and random guys downtown will brag about the deal they got on theirs at a garage sale. In Hamilton alone there's bike co-ops, mass bike-rides, bike racing (mountain, road, cycross, cross-country, and possibly soon track), mountain bikers and BMXers jumping off concrete structures downtown and even once-or-twice-weekly games of bike polo. Cafes sport their own cycling teams, north-enders repair bikes on their front lawns for extra cash and intrepid welders put together their own tall-bikes and recumbents out of old frames. There was even a Bicycle Opera at one art crawl.

Almost none of this was put together by any government program, or with much funding (the university does give a little to MacCycle and RecycleCycles, but that's about it). Nor have any big bike manufacturers or many of the dealers in town taken much initiative. It is a genuine, grass-roots community movement, and it can be witnessed anywhere from Victoria to Halifax, or San-Fran to New York. As anyone who's gotten into the world of cycling knows, it becomes something of an addiction, as well as a community.

Alternative transit takes off where it is more than a form of transportation - where it becomes a part of your life. Maybe that means throwing parties on buses and subways (you'd be amazed at how many police got called in when this was tried on the TTC a few years ago), or maybe it means a more comprehensive network of walking/cycling paths like the waterfront trail. I suspect, though, that the initiative will have as much or more to do with people like us than any decision makers at city hall.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?