All literature is about loss, and Malcolm Lowry and Proust are each exceptional in their hourly agonizing over, and meticulous accounting of loss.

By Mark Fenton

Published November 04, 2008

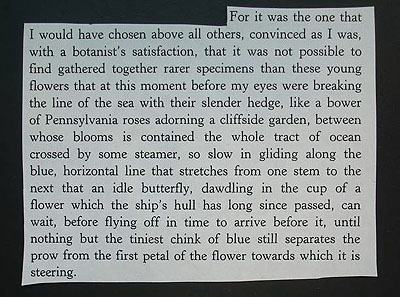

I have learned a few things about essay writing. I used to like putting a block of a favourite text at the head of an essay, either as something that I would unpack later, or as an encapsulation the essay's themes. A lot of people tell me that even though these quotes are, they guess, OK, in their decontextualized state they can sort of be yawners and I'm losing a whole bunch of readers by doing this.

So. I typed a sentence from Proust. It took a while. I highlighted it. I ran Word Count. It was 149 words long. I had just lost 98% of my readers.

My solution?

A stratagem. I would reproduce the visual FACT of the sentence as a photograph. Please only read it if you feel you absolutely need to.

Marcel Proust. Within a Budding Grove, p. 516, (1919) Translation by C.K. Scott Moncrieff and Terrence Kilmartin and revised by D.J. Enright, [and I'm wondering if future crews of Proust translators might exceed the number of persons on the panel that translated the King James Bible.])

Backstory. Marcel, the narrator (we only learn his name a thousand pages into the novel - same name as author ... oooohkaaay - and since I've just officially lost all control of what's happening between these parentheses it's probably as good place as any to put the spoiler warning here) is a frail over-privileged aesthete who will never be expected to do much to have earned his exquisite advantages.

He's always sick and sleeps most of the time. Here we catch him in adolescence, and despite an unimpressive c.v. he's proven astonishingly good and getting girls. I'm guessing family money is the asset here.

The "flowers" he mentions are a metaphor for four teen-age girls he's been watching on the beach at an up-market resort at Balbec for, oh, about 100 pages. I really like this metaphor, girls morphing into tall flowers perhaps like the flowers on the rail of his hotel balcony. The girls stand on the beach, their slender bodies interrupting the horizon of the sea.

Then the metaphor switches back to ACTUAL roses. In fact, type specific "Pennsylvania" roses that, though only inches apart, frame a huge section of ocean in the far distance.

I'd never heard of Pennsylvania Roses, which were obviously a big deal in France circa 1900. So I Googled 'Pennsylvania Roses' expecting them to be as specific and perpetually sought after as Boston Ivy or Buffalo Wings.

Nothing. The closest I got was a YouTube film of a Rose Garden in Bethlehem Pennsylvania.

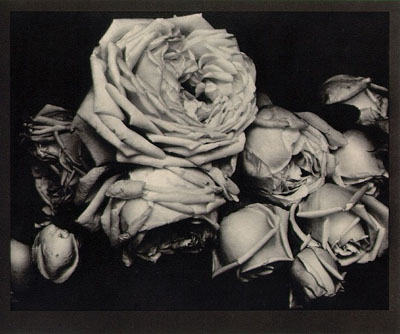

The voice-over describes as "a photographers dream and a rose lover's paradise" which prose I think you'll agree is neither Proustlike nor particularly edifying w/r/t botanical breeds. I still remember the first time I saw "Heavy Roses," the 1914 photograph by Edward Steichen

Heavy Roses

Here's the standard gloss on this piece: just as it was the last good moment for these beautifully and poignantly wilting flowers, it was last photo Steichen took before the outbreak of WWI, so metaphorically it's the last good moment for a beautiful and poignantly wilting Europe. That's not what interested me. I was interested to learn that because rose generations are so heavily engineered by breeders, the look of roses is always changing, and some become extinct. Steichen's picture captures a rose that doesn't exist anymore.

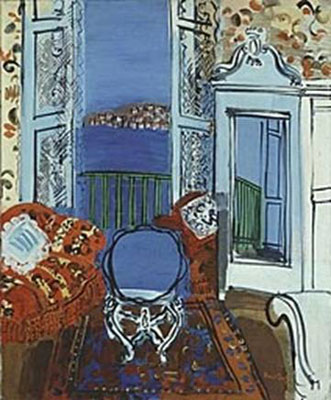

Having hit a dead end with Pennsylvania Roses, I went back to the sentence and decided to consider the steamer that crosses between them. The painter I always think of when I read the Balbec section of Proust is Raoul Dufy. Like Proust he had an unapologetic love of luxury and easy prettiness. His best period corresponds with Proust's career. He's fond of expensive places by the sea in France or French North Africa.

And there are lots of boats in his pictures.

If I'd just been looking for a steamer, this picture would have done nicely.

But the picture that captured the essence of the Proust sentence was a Dufy I couldn't find on the internet, but one which I knew existed on an old Penguin edition of Ultramarine, Malcolm Lowry's first novel. The picture depicts two ships on a very distinct horizon. Unfortunately I lost my copy of Ultramarine years ago, which irks me more than I can say.

So for lack of the right Dufy I had no choice but to try to get a picture of a freighter on Hamilton Harbour and insert it in the text. Here.

This isn't a freighter and there's no way of putting it against the horizon in a photo, and I didn't have my own children with me and I just knew how suspicious I must look to security people.

I went closer to open water confirming my suspicions that this was the most boatless afternoon in Hamilton's history.

I thought about going half way to the bridge and if I still didn't see a freighter to go half way again, but I was already starting to feel I was living Zeno's paradox of the runner, who, in traversing a line from a-z, has to reach midpoint n between a and z and then has to reach midpoint o between n and z and then has to reach midpoint p between o and z, ad infinitum and thus, at least within the capabilities of classical Greek mathematics, never reaches z. (This incidentally is often how I sometimes feel when I'm reading Proust.)

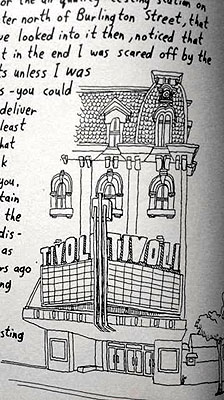

I'd parked in front of the Hamilton Port Authority building which isn't hugely relevant to this essay but this essay IS appearing in Raise the Hammer, and it's a great Hamilton building and so I'm going to talk about it and, by example, encourage people to wander freely in it.

Note they've played up the nautical theme by putting in this figurehead-of-stern-dude-with-strong-cheekbones-and cool-headwear-on-a-ship's-prow.

The building has historically resonant metalwork even on the elevator door.

It's the kind of building I imagine men my grandfather's age working at: guys who put on the same suit and went to the same office everyday for 40 years and sat at a big oak desk in their OWN OFFICE and a woman in nylons and pointy glasses brought them files. I'm not saying I want to go back to that, I'm just saying it's where my mind goes when I'm here.

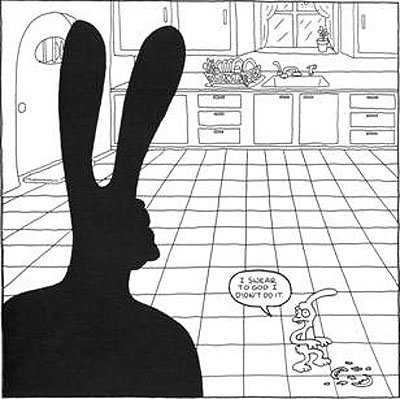

I was just about to get a shot of the glass counter full of Old Dutch potato chip bags - where do you ever find THOSE these days - at the commissary to the right of the elevator, when the guy buying stuff there started eyeing me and my camera. I left quickly as I wanted to avoid a conversation like this.

Respected Hamilton Port Authority Employee: Can I help you with something?

Me: Um, actually just taking some pictures.

RHPAW: Pictures?

Me: That's right. I'm on a photo tour.

RHPAW: We don't actually offer tours of the building.

Me: No. I mean. Here's the deal. I'm writing a piece on a sentence by Pr-um ... OK Cut a long story short. I actually ... I used to have a book by Malcolm Lowry ... The ... He's an author. A Canadian author actually. Sort of ... Anyway I don't have the book anymore, but there was a picture on the cover I really needed, and I thought I could get a picture LIKE that around here ... .and I actually DIDN'T get a picture but I thought since I was here I might do a tour of the building.

RHPAW: Kind of a funny place for a tour. Don't you think?

Me: Well. I mean everyone's different. Since we're talking about Malcolm Lowry ... Before he moved to Canada he grew up in Liverpool. That's in England. But you know that. Anyway his favourite place to go was the Syphilis Museum. At 29 Paradise Street.

I guess it was ... like ... where here's this horrible and avoidable disease that you JUST DON'T WANT cause here's some skeletons and photos and stuff in jars that show you what hideous things it can do to you. I've never been to Liverpool but I'm guessing they have more reproductive education in schools now. It's not there anymore. The museum. But it had a strange hold on him. Malcolm. Lowry. But this is all just by way of saying you'll probably agree that what I'M doing isn't nearly as weird as-

RHPAW: You maybe should just go.

By this time the day was feeling really wasted and I was becoming more and more obsessed with finding the Roaul Dufy painting. I decided to do an emergency visit to the Hamilton Public Library, but all the Dufy books were "on hold." I seriously considered asking a librarian if there was some emergency measure where they could pull books out of hold for someone under a deadline to produce a photo essay, and I won't transcribe how I think that conversation might have gone.

So then I did an emergency visit to Mills Library at McMaster University, where I have neither lending privileges nor business being, but I could get a photo from a book maybe. I was starting to know the escalating anxiety and dangerously impulsive decision-making processes of a man like, say, Malcolm Lowry who needs to feed a pathological addiction at any cost. I sensed I was starting to lurch more than walk.

A lot of people feel depressingly old when they return to a university campus after years of not being a student. The young in love and in one another's arms, etc. Can't say that I do.

Maybe on a sunny day in spring. Not at least around this lot today, who I felt were all pretty scattered and alone and not even as kinetic as one of those Breugels with people sprayed from corner to corner of the canvas.

The only difference I'd noted between me and them - the McMaster students - was that I was the only one with his head wired into an iPod, (running through some frantic UK Dubstep playlist which wasn't doing my 'state' any good.) And I don't know why my brain is going all these kind of irrelevant places except that I'm at this point certifiably manic and crazed.

I found lots of Dufy reproductions but not the one I was looking for. On the walk home I tried to take my mind off the lost Dufy by thinking back to Proust and his long description of teenage girls playing inanely together day after day. In what I'll call a media epiphany, I realized that the obvious contemporary correlative to Proust's Balbec maidens is Teen Girl Squad, substory of Homestar Runner, the flash animated internet cartoon created by Mike Chapman and Craig Zobel.

If, like me, you routinely burned company time staring openmouthed at homestarrunner.com until management wisely made the IT guys lock it behind Websense, you'll know the premise, than which it doesn't get much simpler. If not, here it briefly is.

TGS are "friends" whose interests involve abusing each other, "totally crushing" on boys, and pretending they're older than they are - not so different than the band of girls in Proust - Sure, there's gratuitous violence where TGs get run over and "lathed" and die only to be reborn in the next episode, which except for Albertine's weird death and, at a stretch, her "rebirth" in Marcel's obsessive memory doesn't fall into the set of Proustian events.

But multiple deaths of a single character are I think a convention that's embedded in the DNA of cartooning. Significantly the entire TGS series is a meta-sequence "written" and performed by Strong Bad within the overarching plot of Homestar Runner. That's right. Very like how Marcel - the character - midway through In Search of Lost Time begins to write the book we readers then get to spend quantity time with.

Here's my idea.

In Search of Lost Time: The Graphic Novel.

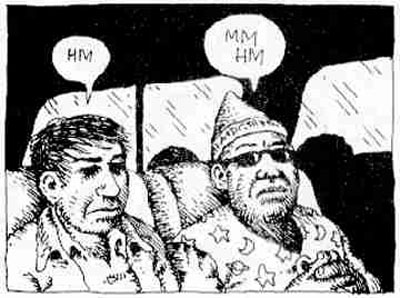

At 3000 pages, adaptation is way too onerous for a single cartoonist. I envision an army of cartoonists each taking little sections, I haven't got my ideal delegation yet, but in addition to Mike Chapman and Craig Zobel for the 'Girls at Balbec' section here are a few of my dream designations.

To avoid getting too turgid too fast I'm thinking some minimalist like Matt Groenig for the early pages of young Marcel in bed cogitating on all his anxieties.

For the back end, where Marcel is dying, Harvey Pekar and Robert Crumb working together as they've done in the past might strike just the right note of terminal decay.

If we could get him it would be nice to keep Hamilton's own David Collier on salary in France, as a kind of in-house cityscape guy. He has a knack for buildings of a vanished world.

And Charles Burns is a no-brainer for the dark eroticism of the Albertine section, and the havoc of obsessive passion and jealousy she visits on poor neurasthenic Marcel.

I had to return to my Proust sentence, two thirds done, without having found a satisfying visual for the ship on the horizon. The final double image of the sentence is complex: the butterfly in the foreground moving across Marcel's gaze more rapidly than the ship in the distance moves across Marcel's gaze. In fact the sentence cuts off before the ship can ever quite reach the flower towards which it is headed (and heaven only knows where TGS has run off to by now. Probably to hunt down some Lunchables or else three of them have ganged up and are throwing sand at The Ugly One)

That evening it occurred to me why Zeno's paradoxes had been on my mind. There is a visual parallel between Proust's sentence and Zeno's paradox of Achilles and the Tortoise. I'm aware that this is an aesthetically heartfelt but scientifically mundane phenomenon of perspective rather than the mathematically slippery concept of infinity along the number line. I'm equally aware that this kind of whimsical gearshift is not unrelated to why I'm never called to chair mathematics seminars at Cambridge.

Some households treat the home coffee-table with product that makes it so shiny objects on it appear doubled. We, on the other hand have treated our coffee-table with product that makes it as matt as can be. Yes. We have painted it with blackboard paint so we can write on it with chalk. This is so we can draw fun things on it and jot down lists and phone messages, but also so we can demonstrate mathematical principles and solve word problems and encourage our children to do these things too and, I don't know, maybe that will inspire them to go for some post-secondary later on.

So I'm sitting at home with my daughters and decide to explain the paradox of Achilles and the Tortoise, partly for their own education, but as much for my own process of understand Proust's sentence and the whole journey I'm on with Raoul Dufy and Malcolm Lowry and how I'm not feeling like I'm getting any further ahead on a big mess of stuff I'm wanting to draw together and try and foist on RTH readers as a lucid essay. So I tell them - my daughters - that Achilles runs 10 times as fast as the tortoise. So they - Achilles and the tortoise - both start at a but Achilles gives the tortoise a head start and doesn't start running until the tortoise gets to b.

Sure, Achilles gets to b fairly quickly - in fact exactly ten times as quickly as the tortoise did - but by THAT time the Tortoise has gotten one tenth of the way beyond b (however small that distance probably is by now) and we'll call that c and by the time Achilles has gotten to c the tortoise is one 10th ahead of THAT distance at d and so on ad infinitum. OK my spaces aren't diminishing in increments of 1/10, but despite my having just pitched out the dying roses, the coffee-table's got all kinds of stuff already on it and drawings they don't want to erase so my spacing is impressionistic.

(All the time I'm explaining this I'm getting the same glazed looks I used to get when the children were very small and there was that thing where you tell them there's an individual Santa who lives at the North Pole and delivers to > 1 billion children in one night and then the kids see about THREE different Santas at THREE different malls all on one Saturday, and all of them look different from each other, and they go "what's with THAT". My response was consistent. I'd say that the best way to think about it is that there is one REAL Santa that no one has ever seen and it's better that way and that what they're seeing is, as it were, sporadic projections of the REAL Santa so no doubt the images are shifty and hard to pin down, rather like the shadows on the wall in Plato's Cave, and remind me to go over Book 7 of The Republic with them when we get home.)

Anyway when I finished what I thought was a pretty good explanation of Zeno's paradox all I got from my youngest daughter was: "Who's Achilles?"

I'm just about done here. I located a copy of the Malcolm Lowry novel with the Dufy on the cover at eBay.co.uk, but it wouldn't let me copy the photo. Maybe fate is telling me to accept losing it. All literature is about loss, and Malcolm Lowry and Proust are each exceptional in their hourly agonizing over, and meticulous accounting of loss: the losses of every relationship, every virtue, every moment of happiness, every memory, every hour of time in life's brief journey. As though writing in outrage against losses could buy them back.

I'm going to send this essay off now to Ryan at RTH, and lose control of it, and lose something of how it is right now as he edits it (no doubt for the better). No writing is ever perfect or in the control of one person, and that's a good thing because neither is anyone's life, and I've always enjoyed this little poem of Malcolm Lowry's about how the typographical mistakes in a piece of his actually amplified it's meaning, albeit in a bone-chilling way, redolent of loss.

Incidentally, this poem was published posthumously. Scholars rage over the way Earle Birney freely "deciphered" it from Lowry's barely legible handwriting.

I wrote: in the dark cavern of our birth.

The printer had it tavern, which seems better:

But herein lies the subject of our mirth,

Since on the next page death appears as dearth.

So it may be that God's word was distraction,

Which to our strange type appears destruction,

Which is bitter.

By Fan-ton (anonymous) | Posted November 06, 2008 at 13:39:50

Mark's photo essays have long been my favorite thing on RTH, but lately they're fast moving up my list of my favorite things on the entire Internet!

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?