Cerebral misadventure meets cerebral faux-krautrock.

By Mark Fenton

Published April 30, 2008

Man is a god when he dreams; a beggar when he thinks-

- Friedrich Hölderlin

The situation is as simple as it is devastating. Jean-Dominique Bauby has suffered a cerebral misadventure. When he regains consciousness he can't move. He has the use of one eye and one ear. Intellectually he is intact. The neurologist tells him he is suffering from Locked-In Syndrome. Good name for it.

He is 43 years old and a senior editor for the French edition of Elle magazine. I haven't been to France but my experience in the Toronto publishing world tells me that jobs like this don't just fall into a person's lap. Jean-Do is a man of will and ambition, qualities little altered by the accident.

With the help of an amanuensis he can communicate. She reads the alphabet (in order of most common to least common letter); he blinks when she hits the right letter. Thus words are formed and he writes a memoir entitled The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, which is published to favourable reviews (could even the most hard-hearted reviewer give this superhuman achievement less than a B+?)

A few days after its release, Jean-Do dies of respiratory complications.

I have not seen a movie in a theatre for some time. I have grown accustomed to watching films only after the DVD release, on a laptop.

This way I can watch a film on my own schedule. I can pause it and return to it as I please.

This wasn't always the case. In my late teens and twenties I used to see at least three movies a week in theatres. I went alone and loved this immersion in a dark womb shared with strangers, staring up together at an artist's vision of what the world might be on our being expelled back into it.

It never was that, so I'd go and see another movie a few days latter. It was, I suppose, a kind of sickness.

I don't do that anymore. At some point I seem to have decided that it wasn't enough to experience life through someone else's celluloid images. That it was time to freeze reality into my own images.

I was down at the Hamilton Harbour Lift Bridge doing just this,

when I received an email from Jennifer Dawson (a cultural anthropologist who appeared as a co-traveller in the November 8 07 issue of RTH, and yes, inquisitive reader, it seems we have become something more than a just a team of ethnographers) on my Blackberry, asking if I'd like to see Julian Schnabel's film adaptation of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly shown as part of the AGH film series.

It was strange for me to go back to that way of seeing a film, that mixture of chance meetings, people I recognized but didn't know, and total strangers. I had grown used to having absolute control over who I watched a film with. And at home, if a scene becomes frightening,

I can put down the laptop, leave the room, and take some different air. I'd forgotten what it's like, once the lights go down, to be locked in.

Of course I didn't just go to movies. When I was 17 I had a job distributing meal trays to inmates of the University of Alberta Hospital. Aesthetically it was quite satisfying. I had the 4:00pm to 8:00pm shift in the summer. There are few physical sensations as pleasing as the Western evening sun streaming through institutional high windows to glint off stainless steel bedpans.

However, given my over-privileged suburban experience, the job was a rude awakening to injury, illness and terrible loss. I was particularly affected by the teen ward. Placed all together despite suffering from a wide variety of afflictions (teens are best clumped away from all other age groups was, it appears, the philosophy) their pathology was otherwise unrelated.

Some were facing recent disability due to motor vehicle accidents. Some had terminal diseases. One young woman, whom I presume was suffering from a degenerative disease of the nervous system, was terribly emaciated and could move nothing but her gigantic eyes which surged hungrily to see the television above the nursing station as though her eyes were arms that could tilt the screen more her way.

They were my age and collectively I felt they were speaking to me. And this is what they said: Your good health could vaporize at a moment's notice. This could be you tomorrow. Know that the mental life and the physical are inseparable, and that a life reduced to this physical state is unthinkable.

In retrospect, nothing I saw or heard suggested that these patients were overwhelmed by anger and despair. They talked about the same things my friends at school did. The same vulgar jokes, the same teenage self-consciousness, the same flirtations, alternately aggressive and vulnerable. They were lively and engaged. It was me who was isolated. Who just went to movies. Who was afraid to live.

That same summer I came upon a story by Jorge Luis Borges called "Funes the Memorious." Ireneo Funes is thrown from a horse and becomes paralyzed. The news is related in a few sentences.

A little later he realized that he was crippled. This fact scarcely interested him. He reasoned (or felt) that immobility was a minimum price to pay. And now, his perception and his memory were infallible.

It was the second sentence that startled me. Was Borges playing it for laughs, or was this the most repulsive statement I'd ever read in a short story? Every day I walked among people who would trade every advantage of their past life to regain the use of a healthy body.

A polymath intellectual prior to the accident, Funes' life after it is purely sensory. And what extrapolations of the sensory world he has! Unlike us, he doesn't simply see a glass of wine, he sees the vineyard it came from, and each grape that went into it.

He remembers a day in such detail that the next day he can describe it so completely that it takes an entire day to tell. (Thankfully Borges doesn't have Funes "do" one of these descriptions for us).

So overwhelming is every aspect of an object, animate or inanimate, that Funes wishes he could give a separate name to each "view" of a person or thing, over time. So thrilling and powerful is even the most mundane experience that Funes can barely sleep.

Five years after his accident, Funes dies of respiratory complications, having by our standards, it is implied, lived many lifetimes in those few years.

Borges was blind. He knew something about disability. And no doubt some part of his singular imagination was enabled by sensory deprivation. Still, I had trouble buying into the over-fulfilled life of Funes.

I don't want to suggest that Jean-Do is as laissez-faire about his paralysis as Funes. Jean-Do is very interested indeed that he has lost the use of his body. Yet when he tells us of his anguish in passages which are undoubtedly real, they aren't the most memorable in his book. As here for example, when he's at the beach with his family on Father's day:

blockquote>Sylvie and I remain alone and silent, her hand squeezing my inert fingers. Behind dark glasses that reflect a flawless sky, she softly weeps over our shattered lives.

The only thing that saves the passage from absolute triteness is the detail of the sunglasses. A nothingness of darkness mirroring a nothingness of light. A characteristic hunger for the sensual world, which, in this case comes up empty.

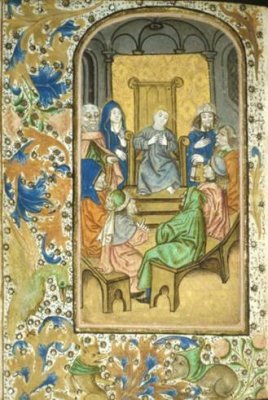

It is in the passages where his imagination takes over that he is the most memorable, and in which he approaches the state of Funes. These form the bulk of the book and are amplified still more in Schnabel's film. In one chapter Jean-Do dreams that the medical staff, who have both helped and exasperated him, have been rendered in wax, like the figures he remembers from the Musée Grévin in Paris.

Some of these figures were very poor likenesses. To get them right you would need the talent of one of those medieval miniaturists whose magic brush brought to life the folk who once thronged the roads of Flanders. Our artist does not possess such skill. Yet he has managed to capture the youthful charm of the student nurses with their dimpled country-girl arms and full pink cheeks. As I left the room I realized that I was fond of all these torturers of mine.

We have four leaps of memory and imagination here. First the memory of figures he once saw in a wax museum; second, a vision of his care-givers done in wax; third, a memory of medieval Flemish miniatures; and fourth, how his caregivers might be if Flemish miniaturists were around to illustrate his dream; this last group just out of reach, and, paradoxically, the more vivid for that.

Any description I'd give of the Schnabel's recreation of imagined sensory experience - the beaches, the oceans, the glaciers, the little dramas involving rescuers from the ancien régime - would diminish their effectiveness. It's not what they represent. It's the mere fact of powerful, imagined events created solely for the creator.

The one thing I would note about Schnabel's version which perhaps out of modesty is only hinted at in the book is Jean-Do's interaction with women: the therapists, assistants, and former lovers who dance through the film. Jean-Do likes women, and women like him, as much after the accident as before. (In fact, in consideration of his physical immobility, his now all but omnipotent women acquaintances are still less reserved in giving of themselves.)

He has his moments of despair, as one would expect, but he is strangely free of self-pity. Even his inner bitterness and hostility to the hospital staff are delivered with panache and an amused, if sardonic, detachment that is charismatic. It is remarkable how little his personality has changed following the accident. Perhaps, we dare to hope, the human spirit can transcend the prison of the body. I expected to be moved by Jean-Do's plight. I didn't expect to envy him.

Is it possible to achieve an exalted, even desired, imaginative state after the collapse of the body, as Borges tells us Funes did? It's a question Jean-Do could answer, and I'll content myself in being fortunate enough that I can't. I'm still doubtful. As I returned to the Hamilton Harbour Lift Bridge, I basked in my ability to move about as I pleased and feel the wind and damp and cold, and wonder at the technology of the lift action and my luck at arriving just as it began to rise.

The proximity to open water and boats reminded me of the scene in Schnabel's film in which Jean Do is on an outing with his assistant. The effectiveness of the music in this little scene is easy to miss. It consists of a loop of the short instrumental break from "Pale Blue Eyes" by the Velvet Underground.

Like most people who went to university in the '80s, I've heard this song way too many times, but if you haven't, there's a veiled thematic link to the story, in that the lyrics of the song are about the singer's loss of a women, a married women from the sound of it, - or perhaps it's about his inability to ever really have her.

In any case the tone is gentle, a longing that has resigned itself to impossibility. What remains is his memory of her pale blue eyes (the very paleness suggests he's struggling to prevent this last essential memory from fading out.)

Eyes are everything in The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. Jean-Do, only has an eye to communicate, and he and his friends need to maintain full eye-contact all the time in order to speak. But the film only references this tangentially, since all Schnabel gives us is the instrumental portion, a soft static pulse, which keeps reappearing from beneath the film's dialogue and ambient noise, just when we think it's gone for good. It is the perfect correlative for a scene of Jean-Do with his assistant, on a boat together on a perfect day. And for memory remaining afloat despite time trying to submerge it.

I was standing by the Hamilton Harbour Lift Bridge trying to bring up Pale Blue Eyes on my iPod, when my Blackberry buzzed. It was Mark Knackstedt (who has appeared as a fellow-traveller in previous issues of RTH and was even good enough to serve as model for a sketch by Knet Marnof, the well known Icelandic sculptor and lithographer, in the October 6, 2006 issue) reminding me we were to see Acid Mothers Temple at the Horseshoe, in Toronto later that week.

Best described as Japanese heavy psychedelic band with roots in the late middle ages, Acid Mothers Temple is the prefix of any ensemble lead by Kawabata Makoto, who releases

about three albums a season, and the ensemble I saw was Acid Mothers Temple and the Melting Paraiso [sic] Underground Freak Out. (Not to be confused with Acid Mothers Temple and the Cosmic Inferno; Acid Mothers Temple, Stones, Women, Records; Acid Mothers Gong; Acid Mothers Temple and the Pink Ladies Blues; Acid Mother Temple Afrirampo [your guess is as good as mine], and finally, with a slight twist on the name which suggests to me a focused personal expression on the part of their leader, Kawabata Makoto and the Mothers of Invasion.)

Kawabata is pictured above on the far right, playing a very cheap guitar (Mark Knackstedt, a guitarist himself, noted this for me - where would I be at these events without insider knowledge?) the reason for which was that during his final freakout of the concert he flailed it upwards into the wiring above his head where it was finally abandoned, limp and spent, like a kite captured in hydro lines.

Imagine a mix of late '60s psychedelia, '70s heavy metal, British progrock, Krautrock, the American minimalist avant-garde of Steve Reich and Terry Riley, and medieval music, put together with an instinct for proportion, flawless pacing, and taste, while still retaining the excitement of an improvisation.

Note, too, that the sense of what's cool in the west is of little interest to AMT. They will happily reference Deep Purple and The Velvet Underground on the same album if not in the same song.

More eclectically their songs are frequently informed by the music of the Troubadours, that kindling for a proto-renaissance which flared up in 12th Century Provence (or Occitan, as the AMT CD covers refer to it) against the waning dark ages.

If you've never experienced this strange poetry set to music (the poetry a mixture of courtly love, chivalry, Christian piety and mysticism) I would recommend any Troubadour recording by the Clemencic Consort

who bring a miraculous balance of historical accuracy and spontaneity. Cursory surfing tells me there are CD transfers, but my memory is of returning from my shift at the University of Alberta Hospital, grabbing some Clemencic Troubadour vinyl, sliding a needle in the groove and disappearing to a distant time and place.

The Clemencic Consort emulates the jam sessions that Troubadour performances probably were (I suspect they used cheap lutes and viols in case things got real wild and they ended up smashing them against the amps).

AMT is not so authentic. It is faux Troubadour music. The effect of the drones and what sound amazingly like shawms or other period reed instruments is inevitably shattered at around the five minute mark, with the arrival of Kawabata's electric power chords. And the language they're speaking isn't Languedoc, though you can't quite put your finger on what it is. I'm no authority, but I feel there are rhythms that could only be east-Asian.

This may seem unlikely music to have come from Osaka. But what happened in 12th century Provence was an amalgam of an astonishingly wide range of cultures (given how local the medieval experience was).

The Troubadours blended a renewed interest of Latin and Greek poetry with indigenous Christian/love poetry and musical innovations from Islam via Spain. In other words they took a bunch of cultures that should have had nothing to do with each other and merged them into a coherent new music.

Erich Auerbach, the great German critic-scholar gives an eloquent description of the compelling inscrutability of the Troubadours in his book Dante: Poet of the Secular World (translated from the German by Ralph Manheim).

Their feeling that they were a special breed of men, an exacting social and spiritual elite, a secret association of the elect, molded their whole inner attitude, their sense of fellowship, their supreme elegance.

Shrinking though our planet may be, the set of traditions that meld seamlessly on an AMT album could be described similarly. (Note to AMTATMPUFO: If you guys are reading this, might I suggest Auerbach's quote on the back of a future album?)

If the band names don't give you a sense of what era and milieu AMT longs for, the album covers will. There are basically two types of AMT album art. The first is the most descriptive of the music.

which suggests a Japanese invasion of Haight-Ashbury circa 1968. The other, becoming more prevalent these days, consists of fairly generic girlie pictures

which, in common with group photos of the band and friends, are used with no irony whatsoever, unless I'm so ignorant of the culture I'm missing the irony.

I actually bought the above at the merch table before the concert, which had a phenomenal selection of the AMT back catalogue on a large black tablecloth surrounded by four men who, in terms of customer service, made the record store salesmen in High Fidelity look like people who really want to move product. (I'm referring to the movie version and, no, I HAVEN'T read Nick Hornby's novel and for crying out loud I went out and bought a copy of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly so I'd look like a responsible reviewer - how much homework must I do to satisfy you people?)

I assumed the guys at the table were roadies, but when AMT came on stage it became clear they were the band.

I also bought this T-shirt

because what the hell else am I supposed to do with my disposable income?

I won't bore you with a description of the concert, but will try and attach the small film I took of their entire encore

And just as easily it could be the neo-Celtic noodling of an early King Crimson album or any British prog rock of that ilk. The recorder solo terminates with a sonic burst by the whole band, or, as AMT refers to it, a "freak out," which simultaneously evokes '50s Stockhausen, '60s free-form jazz, '80s Sonic Youth in their New York noise mode, and other moments of barely controlled expression I don't yet know of.

After that they were gone for good. And so finally were the audience who seemed not to grasp how exquisitely final the encore was and how anything further would spoil its perfection and who continued to stand and scream at the empty stage for a while.

It was an audience of white male ectomorphs anywhere in their 20s who still live with their parents in Eglinton and who think that going to see a Japanese psychedelic band is a bit dangerous. But they were young and healthy and happy and screamed intelligent things like PLAY MORE ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE MUSIC, and the band would look at one another and laugh; good, clean, genuine laughter, and it was beautiful.

Despite the image, the band don't strike me as people who do drugs. The quality, quantity and sheer technical ability requires way too much discipline. Tsuyama Atushi moves his fingers on the bass like a violinist, sings beautifully in ways I can't describe, including throat singing, and can actually make music I want to listen to with a soprano recorder.

A word should be said too about the drummer, who you can't see in my clip. There is no substitute on record for live drumming, the raw feel of percussion as it reverberates off the ribcage, and Japanese drumming is drumming from somewhere else.

Drumming, it feels, of a power that could energize whatever forces elevate the ramp of the Hamilton Harbour Lift Bridge.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?