Whenever I turn down a street I've been away from for a while I'm presented with something in ruins.

By Mark Fenton

Published March 24, 2008

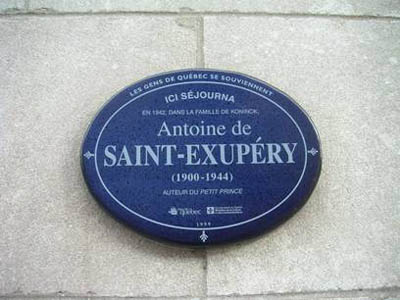

At Pointe de la Baumette on the southern coast of France there is a lighthouse with a tablet recording the end of St.- Exupéry. He disappeared in July 1944, his aircraft one of the many simply lost without a trace in the great sweep of the war.

--James Salter, Burning the Days

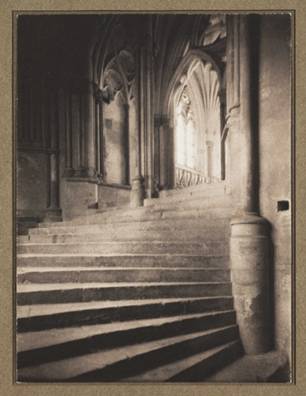

Is Hamilton an archaic industrial city lost in the great sweep of progress? Whenever I turn down a street I've been away from for a while I'm presented with something in ruins. The ruins themselves are striking,

what with the windows and guts of the building plundered, light pouring in and enlivening it, like a gothic Cathedral.

Frederick Evans, 'Stairs to Chapter House, Wells'

And I think: wouldn't be beautiful to make our buildings with the medieval ideal of light streaming in everywhere so that the stone structures appear to dissolve.

However, Hamilton's buildings did not take centuries to build, and do not take centuries to crumble and vanish. Notwithstanding the support this publication has given to preserving old Hamilton, there is a tacit consensus that many of Hamilton's buildings have neither the economic viability to serve as they once did,

nor an aesthetic value urging us to preserve them as objects in themselves. We are not blessed with a will towards preservation as Europe is. Here's an example. Sure there are lots of places to have a church service, even for a really big congregation. Like, say, in a converted, low maintenance warehouse. But people in France choose to support a place like this.

And I don't even want to think of what they need to take from the collection plate to maintain that precarious balance of vaults and buttresses!

I wandered away from the solid but useless government building I'd just photographed, feeling sad as the late winter snow. A block away, I turned, knowing that like Orpheus I was probably hastening my own losses. Here, smack in the foreground was an accidental ice sculpture rising up before the building like a nuclear blast:

a good metaphor for what the city has in store.

Proceeding eastward I cut through the almost empty corridors of Jackson Square and became entranced with these wedding-clad manikins.

In fact I gazed at them so long that the few other passers-by slowed to memorize my features, should they have to describe me later to the authorities.

These are not the utilitarian storeroom dummies designed purely to display clothing, whose featureless visages are compelling for their very evasiveness,

who by expressing nothing express everything. No. My bride and her very young attendants are as carefully defined as the dolls of childhood and, aside from scale, very little different.

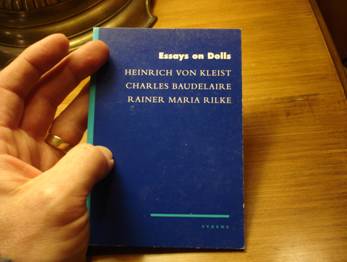

I had been reading Rainer Maria Rilke's "On The Wax Dolls Of Lotte Pritzel" in a small, thin collection of essays on dolls

which as you can tell from me bothering to photograph it in my hand for the sense of scale I like as an object in itself. But I also like to read it. Rilke's essay is a response to a 1913 Munich exhibition of wax dolls. These are not dolls for children. Lotte Pritzel's early works emulated the aesthetic of modernist ballet, and later she was commissioned to make them life size, as dress models.

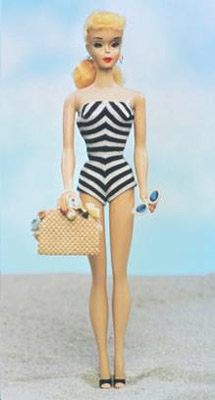

While their proportions may seem to prefigure postwar, anorexic Barbie, they belong to the complex androgynous world of Weimar decadence. Despite the fact that Barbie's measurements in a real person would defy the possibility of reproduction (or for that matter walking or breathing)

her vapid expression and a stance suggesting a weirdly vertical rigor mortis are an antithesis to androgyny, or any kind of sexuality for that matter.

As I had just re-read the essay I was struck by Rilke's thoughts on extrapolating dolls into the adult world

Faced with the stolid and unchanging dolls of childhood, have we not wondered again and again, as we might of certain students, what was to become of them? Are these adult versions of those doll's childhoods cosseted by genuine and feigned emotions?

Without going so far as consulting a nutritionist, I would say that the adult doll of the Jackson Square window is proportioned healthily enough. She is redolent of that precarious crossroads of the girl and the woman; the wedding-day transformation so centuries-old, and of so vanished a set of values that it's inexplicable and unsettling for it to have surviving into the 21st century.

The smaller manikins to either side are that much closer to the dolls of childhood, envoys to a playtime free of adult concerns. The tableau looks backwards in sadness for a lost girlhood, and forward in blind anticipation of womanhood. Or rather, since few things are more "in the moment" than storefront manikins, the tableau is frozen in an eternity between these two states.

If politically troubling, this Western archetype of the bride has so far proven deathless, which may go some way to explaining the endurance of, indeed even a demand for, lavish, expensive and superficially "traditional" weddings, despite marriage being superfluous as a social and economic structure in hyper-industrialized nations.

The struggle to maintain an ideal of marriage and domesticity was on my mind as I left Jackson square walking northward into the city's struggle to maintain some ideal of a downtown and commerce.

I tried to imagine what buildings I could count on remaining as things got torn down or simply fell to ruin from neglect. There is one structure in no danger or disappearing. One structure for which there is something like a general consensus that we not only NEED it but might consider ripping down everything else to build MORE.

That's right: The Parkade.

I walked over to one.

At some point, we will obviously have a state of affairs where having torn everything down to make way for parking we're slightly puzzled that when we get out of our vehicle we don't in fact have an office to go to, just another parking garage.

Might I suggest, then, that businesses purchase buses for office space and park them more or less permanently in parkades. Everything's going wireless anyway and a work station in a bus can't be any more dehumanizing than the average office cubicle.

Think of the advantages. If there's a strategic reason to move the office even a few blocks it will take only a small bite out of the budget and there will be little disruption to company operations.

When times are good it's a great vehicle for awarding employees with a trip down to Vegas. When times are bad it's easy to dodge creditors. Just drive to a different parkade.

So, in the manner that, at the end of Nineteen Eighty-Four, we're told that Winston Smith loves Big Brother, I resolved that in the interest of self-preservation I must love parkades.

Here's what I did. I made repeated trips to the Eaton Centre Parkade on foot. If you have never made a specific trip to a parkade ON FOOT, circumnavigated it ON FOOT and returned home ON FOOT, I'll venture that you've never properly delved into the essence of parkadeness. (Here's a parallel idea I haven't tested. Some day I plan to put my car into neutral and roll it to work and back, and similarly I hope to discover something about the essence of "car"-ness. Ask not what the internal combustion engine can do for you; ask what you can do for the internal combustion engine.)

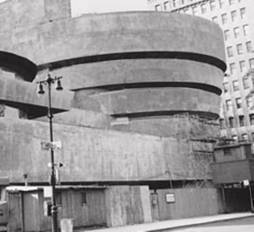

I am always excited when things that no longer exist leave a residue. The Eaton's department store is gone. In fact the corporation went bankrupt in 1999. And yet we are free to park in the Eaton Centre Parkade, and we never question it. Preservation of what has been lost is the job of museums as well. Looking up the ECP's curved, neo-Bauhaus concrete, I made an immediate connection with the Guggenheim museum in New York City.

Obviously there is a difference in exhibits once you get inside. The Guggenheim looks like this as you walk its descending corridor.

No big surprises. Lots of white. Plinths for sculptures. Light that balances visual ease with sensitivity to the preservation of pigments.

By contrast the ECP is mostly an exhibit of the recent history of the automobile.

Once when I was exiting the ECP (in my car - yes - I have my mainstream moments) I suggested to the clerk in the payment booth that the ECP adopt a voluntary admission policy like they have at the Guggenheim.

This got no response so I explained it to her: "At the Guggenheim it's up to you. If you're a millionaire you might feel compelled to leave a few hundred dollars; if you're an art student you might just drop in a dime. I'd suggest something similar for the ECP and you might be surprised to see your revenue increase. There are a lot of fancy cars in here. A guy in a Mercedes is going to go PRETTY red in the face if he lowballs you.

"Now, myself," I continued - to a person whose face was the very definition of expressionless - "I feel more comfortable, given my yearly income right now, paying $2.00 as opposed to the $2.75 the ECP is suggesting, however, should I qualify for the year end bonus as I hope I will you'll see me tossing five dollar bills at you and waving away the change."

"That's $2.75, sir."

I was interested to see that the architect of the ECP had retained Frank Lloyd Wright's

circular window motif,

but climbing the stairwell I felt the ECP bore even more resemblance to the bare unadorned concrete of Le Corbusier,

Corbusier parliament buildings, Chandigarh

whose stark geometry is a prototype for so many 60s and 70s art museums, such that it occurred to me the largely bare walls of the stairwell of the ECP

should dispense with their warnings

(since they clearly don't stop me from engaging in minute observation and recording or the space) but rather use the walls to house those great oriental landscapes made of such unstable material that they demand parkade levels of illumination (that sensitivity to the preservation of pigments I spoke of earlier and which museums are even more ferociously uptight about than usual when it comes to subtle Asian inks on paper.) I'm always squinting at them when I examine them in museums.

Really, all things considered, the parkade would be a better place. I'd put it right where "These premises are..." currently hangs. The grey textured earthiness of the concrete under the low light would fade organically and almost invisibly into the artwork. Vapourous. Ephemeral. A moment in a barely remembered dream...a bridge to a far away time and place. . .the essence of oriental landscape.

As I climbed further it was the round windows that struck me.

Why are round windows so strange a way to look at the world? The lenses of our eyes are round, as is the lens of the camera. An early film image makes this relationship explicit.

It may just be me, but I'm always acutely aware of the circles in the shot of early cinema. I think early filmmakers intuitively tried to frame circles in their picture of the world, having been newly confronted by the circularity of the lens.

Think of the big round moon in Méliès

or, unconsciously, that final bullet hurtling at me, the viewer,

through the circle of the gun barrel, which image in fact stands as either the beginning or end shot of the circular "loop" of the early nickelodeon projections. (I saw this over 20 years ago and I've misremembered the gun barrel as being much bigger in the shot than it actually is, which says either something for my own gun paranoia or the power of a shot which has been repeated countless times since in action movies.)

My favourite early film convention though is the "iris" shot, which plays up the circularity of the camera lens, and supposedly creates an "intimate" shot something like a cameo in a locket (it's used most often to infuse the leading lady with an insipid "softness.")

In reality it serves mostly to emphasize the "fact" of the camera (I assume it was some sphincter-like gizmo on the camera lens that achieved it) and all that black emulsion kill's what little suspension of disbelief I can bring to these early melodramas. While the iris shot was a dinosaur even by the late silent era

it occasionally achieves a nice sense of entrapment, like here, at the end of the same film: the black encroachment of despair closing around her. (I was kind of snoozing as I tried to watch this film on YouTube, but trapped-in-a-moment-of-despair is definitely the mood Griffiths is shooting for.)

So, when I look through round windows I am reminded of the fact that they frame things unnaturally,

and of what a prejudiced and paltry view onto the world they give. I never feel this with rectangular windows. The eye may be round, but most things we make are square. The eye's business is seldom circular.

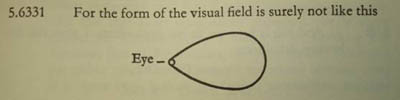

Is this what Wittgenstein is alerting us to in proposition 5.6331?

Later that night I was struck again by how a photographed circle is so often a gateway to disorientation, despair, failure, even oblivion. It was the night of the recent lunar eclipse and rather than simply enjoy it live, I insisted on taking some dismal photographs of it, thus missing the sheer wonder of the eclipse more or less completely.

All my shots were equally unremarkable. I did, however, get some surprisingly good shots of street lights, much closer to me than the moon.

I was prepared to dump everything off my memory stick as a dead loss. Then I accidentally tapped the control on the camera that allows me to see the last nine shots in the viewer, tiny thumbnails three by three, thus:

Sure, most of those heavenly bodies are in fact streetlights. But what a warm and inviting and strange view of the cosmos it gives. I imaged pioneers beyond the earth's surface, seeing the planets, moons and suns in ways they've never been seen before.

I thought of Charles Lindbergh on his transatlantic flight, the stars his only companions. I thought of what the Apollo 11 astronauts might have seen. I thought of David Bowman in his final intergalactic journey in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Most vividly, I thought of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, aviator and author of Le Petit Prince in his many lone travels as a mail pilot, and later in World War II as a reconnaissance pilot, the man who captured early aviation, and in particular the solitude of night flights, with more poetry than anyone I've read.

Was this his backdrop the night he and his plane disappeared over the Mediterranean near Spain, never to be found? There is a section of Le Petit Prince in which the Prince visits men on a series of planets, and this is how I imagine his journey from one planet to another actually looked.

This accidental conglomeration says to me that the deep space beyond what we know is friendly and warm. Even that moon in the bottom left corner seems to be smiling.

Yet when I took these photos, I had no concept that I was compiling an imagined solar system. "It is not the destination; it is the journey" is how I believe the inspirational speakers put it.

On the landing of the 6th floor I poked my head into the parking area.

Looks like not too many cars are able to climb this high. I call it the Stonehenge level. A good astronomer would be able to tell the time based on the date and the angle of light on the columns. Its architecture is stark and seemingly pointless and doubtless the setting for ritual. I think of lines from Wallace Stevens:

...a ring of men

Shall chant in orgy on a summer morn

Their boisterous devotion to the sun,

Not as a god, but as a god might be,

Naked among them, like a savage source.

And can't you just see the orgiastic men circulating wildly here. (Or have the drab indoor days of February finally gotten to me?)

OK. So here's where a walking tour of ECP pays off bigtime. You just walk out through these doors.

and there are no vehicles. Nothing at all. You are alone.

I walk around, free as the pigeons that wheel over the remnants pre-automotive Hamilton.

This level is chained off to vehicles. It's just for pedestrians. I revel in how the ECP has left it bare for my enjoyment. When all the buildings and inner city greenspace have been turned into parkades I would push for leaving the roof level vacant for picnics, roof-hockey, Tai-Chi, Tennis, and similar recreations.

If you are noting a diversity of light and snow and questioning my documentary integrity, you are astute. I went there on three different days, Feb 15, Feb 23 (the night of the eclipse) and Feb 28. The 28th was by far the coldest, brightest and snowiest. This odd mixture of elements made it stark and strange. The light standards cast long shadows.

like the shadows cast by the catatonic guests in L'année dernière à Marienbad

Alain Resnais, 1961

It was a living model for the opening lines of T.S. Eliot's "Little Gidding" the definitive description of late winter days in which intensity of sun and intensity of cold are bafflingly indistinguishable.

Midwinter spring is its own season

Sempiternal though sodden towards sundown,

Suspended in time, between pole and tropic.

When the short day is brightest, with frost and fire,

The brief sun flames the ice, on pond and ditches,

In windless cold that is the heart's heat,

Reflecting in a watery mirror

A glare that is blindness in the early afternoon.

But I left T.S. Eliot's cogitations to enjoy the westward view.

For I have long had a relationship with the vaporous emission, slightly to the left of centre in the shot above, out in full force today. Years ago, before I knew that many people in Hamilton, and before I even had a camera, I would come out to the ECP just be with it.

Some days it is the merest suggestion of an entity, fragile, yet weightless.

Caspar the friendly emission.

On others

it is sprawling, faceless, uncontainable, indefinable. As a god might be.

Once it was curled like a reversed questionmark

reminding me that I would not gain answers from it, only leave with more problems to consider.

Here

it is a terrifying vision of annihilation. A mushroom cloud akin to the accidental ice sculpture presented at the beginning of this essay. I like that dialectic: that hot vapour and frozen water are equal possibilities. If Robert Frost is any authority, things could go either way:

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I've tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

But all of these manifestations are preferable to arriving and finding it

not there at all. Perhaps that's the ultimate and hardest lesson of all. The lesson that our guides abandon us. That sometimes we're stuck out on our own, as alone and absurd as a man in a parkade without a car.

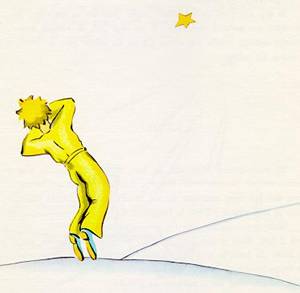

Here is the penultimate image of Le Petit Prince.

The narrator has crash-landed in the Sahara. He has to repair his aircraft as no one thought to file a flight plan or equip the machine with a transponder. As he struggles to fix it, he's visited by a Prince from another planet. We are never entirely sure if the Prince is real or a hallucination, a product of the narrator's unconscious need for a witness to his tenuous survival.

The drawings, by M. de Saint-Exupéry himself, are stylized deco-era figures. Much of the struggle of the book, on behalf of both the pilot and the Prince, is to resist the routine drabness of adult world (Oh, like I have trouble doing THAT) and retain the magic and wonder of a child's eye on the world.

And yet, we learn, the Prince is the lone boy on his planet, without parents, and forced to confront all challenges on his own. As such he is a childish figure contorted into an adult, like the wax models of Lotte Pritzel, and becomes a parent to the aviator, in his parched, anxious, needful delirium.

He confirms the aviator's tenuous existence and enables the aviator's endurance and ultimate escape. We fear the loss of the Prince would foretell the aviator's death. For me the Prince's fall out of existence resonates with the most terrifying words of Rilke's essay.

I have no way of knowing what it is like when a little girl dies and will not let them take away one of her dolls (perhaps one quite neglected up to then), not even at the very end, so that the poor thing, withered and wilting in the burning heat of the child's feverish hand, is carried as a companion into that ultimate and momentous region.

When the aircraft is fixed and the narrator is ready to fly away the lonely planet boy returns to his asteroid - a momentous region if every there was one - vapourizing and falling in the image pictured above: "He fell as gently as a tree falls. There was not even any sound, because of the sand."

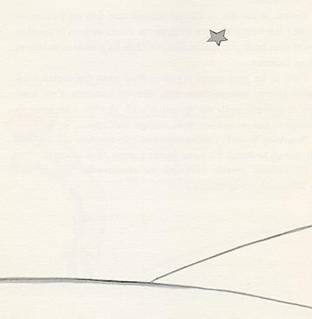

Here is the final image of the book:

followed by the lines:

This is, to me, the loveliest and saddest landscape in the world. It is the same as that on the preceding page, but I have drawn it again to impress it on your memory. It is here that the little prince appeared on Earth, and disappeared.

This is how I feel when I walk the ECP but don't see my puff of vapour in the distance. It's how I feel about the soldier who leaves on a mission and is never seen again, whose remains are never discovered.

And it's what I fear I'll be left with when I try to find something recognizable in the Hamilton I love so much, which is increasingly falling into a desert of remembered buildings.

By trey (registered) | Posted March 25, 2008 at 21:13:14

another great piece from my favourite Hamilton writer.

By piggyman (anonymous) | Posted April 23, 2008 at 08:10:30

great piece. you are a great writer. As a former Hamiltonian and occasional visitor I feel sorry for the city. Its been discarded and given up for because of its industrial base.

Too bad. it really is a great city. I cant believe the central core is so delapated. Where else in North America can you buy 3,000 sq foot beatiful century home 40kms from downtown toronto for 169,000. Nowwhere.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?