Such is the human spirit that it overreaches itself.

By Mark Fenton

Published December 20, 2007

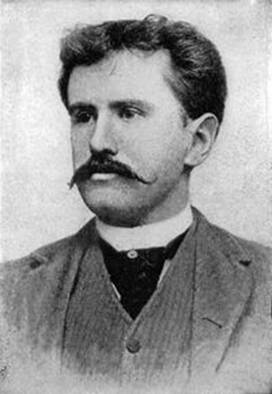

Like everyone who sits down to write something for Christmas, I'm daunted by the existing literature. The very thought of O. Henry creating "The Gift of the Magi" in a booth at Pete's Tavern New York a few hours before deadline is dispiriting. I have a mental picture of O. - Moustache waxed and waistcoat neatly buttoned -

enjoying a tasty unpasturized ale and writing fine copy with a pen he dips in an ink well. He doesn't spill a drop of the ink. Or the ale.

I'm sitting at my computer in jeans with a Starbucks-bought coffee I've already spilled down the sides of my travel mug, and my handwriting has atrophied to the point where I can't make legible copy with a ballpoint any more, let alone a fountain pen.

Between myself and the words that come up on the screen, I'm dependent on binary sequences I don't even understand. Add to that that my iPod has just shuffled to the eponymous track of the eponymous Black Sabbath album, which I KNOW I have no one but myself to blame for downloading, but it's still antithetical to the Christmas spirit I'm supposed to try and get in.

I consider that at this point the literature around Christmas is so large that if it were all printed and placed in a single building, that building would immediately collapse.

This causes me to consider wild feats of architecture in the name of religion: monuments of transcendent aspiration. I had been reading Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres, by Henry Adam's (incidentally a contemporary of O. Henry and you can see they buy their ties from the same haberdasher)

His broad history of the middle ages begins with a consideration of the precariousness of location and difficulty of building a foundation for Mont St. Michel:

Instead of cutting the summit away to give his church a secure rock foundation, which would have sacrificed about thirty feet of height, the Abbot took the apex of the rock for his level, and on all sides built out foundations of masonry to support the walls of his church [...]

Abbot Robert de Torigny thought proper to reconstruct the west front, and build out two towers on its flanks. The towers were no doubt beautiful, if one may judge from the towers of Bayeux and Coutances, but their weight broke down the vaulting beneath, and one of them fell in 1300. In 1618 the whole facade began to give way, and in 1776 not only the facade but also three of the seven spans of the nave were pulled down.

Such is the human spirit that it overreaches itself.

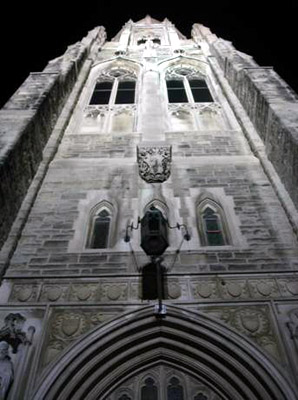

As an exercise of misguided engineering and dubious political will, I know of no correlative to the Cathedral of Mont St. Michel in Hamilton-my gut tells me to shy away from a comparison to the Red Hill Creek Expressway-but as I write this I have the good fortune to be staying with a family who lives a mere hundred yards from the grounds of Christ the King Cathedral.

It may not have as dramatic a seat as Mont St. Michel, but according to Wikipedia it boasts "television screens installed on the side columns holding up the cathedral ceiling."

Perhaps Henry Adams' single most famous essay is "The Dynamo and the Virgin" written around 1900 and forming a chapter in his biography "The Education of Henry Adams." Struck by the complexity of the internal combustion engine that has just been demonstrated to him, he meditates on the unified force of medieval Christianity in the cult of the Virgin Mary, and the multiplicity of forces he sees in the new technology around him.

He doesn't favour one over the other, he's just aware that he's at the beginning of a new age and - in a refrain that repeats throughout his book - his education is of no use in making sense of it. And he is wary of machines feeling that humanity must master them before they master humanity. (This trepidation around new machines would cast a shadow over writing about technology throughout the 20th century.)

What, I ask myself, would Henry Adams have thought of TV screens in a Catholic Church that clearly emulates medieval design?

The family I am staying with is in possession of a work by Susan Roth, an American painter whom I have long been a fan of, and part of my motive for being here is to get a good look at it. If you regard Jackson Pollock as a bland traditionalist mired in a centuries old tradition of European oil painting, Susan Roth might be the painter for you.

The family, I discover, is divided into two camps: those who find the painting a wicked-cool construction of heartrending beauty; and those who find it just plain messed up. The eleven-year-old daughter is of the former camp, which is why it's in her room.

She let me take a picture of it. I didn't ask her to move the items around it because I wanted you to get a sense of scale. Really, I believe art is best seen in people's homes and I'd love it if in museums had their artworks propped up behind random clutter.

I tip it on its back to give you a sense of its relief (this is an option for display).

It's next to impossible to convey the material. That wet-sand-like stuff at the base appears on closer inspection to be some gritty synthetic. (I'm told the making of it is a secret between Roth and a polymer-chemist she consults with.) On top of that is a stack of (comparatively) conventional paint, a swamp of layered acrylic gel from which emerge arcs of home-made stained glass, organic forms that entwine like copulating serpents.

On first viewing you might say this picture is all about texture: texture without drawing or narrative. But I am always suspicious of things that appear merely textural, in light of a quote by Brian Eno:

Texture is only form looked at from a distance. If you look at this carpet, you perceive it as texture, but if you looked closer, you would see that it's actually a whole lot of forms.

And one can experience this painting both ways. You can view it as a micro world of the vaguest textures. Or you can get close and experience it as a world as detailed as any, with its own logic of mountains and rivers and crevasses. A coherent, if invented, set of surfaces, colours, materials, masses.

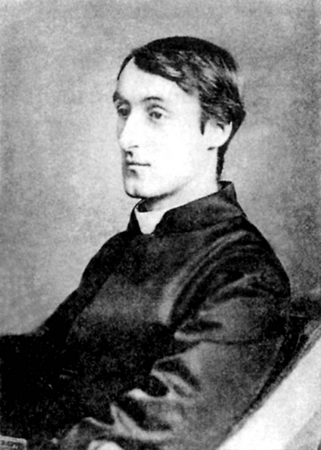

Or have I moved, not outward, but inward? Into some terrifying and soul testing and strangely invigorating geology of the brain? Now the words that run through my head are from Gerard Manley Hopkins, the 19th century proto-modernist poet and Jesuit Priest (so, like, no tie

to compare with Adams and Henry) from his period of spiritual crisis:

Oh the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall

Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed. Hold them cheap

May who ne-er hung there. Nor does long our small

Durance deal with that steep or deep.

I got done looking at it and went up to the attic and invited the daughters for a walk around the vicinity of Christ the King Cathedral. They were, however, absorbed in watching High School Musical, on a laptop.

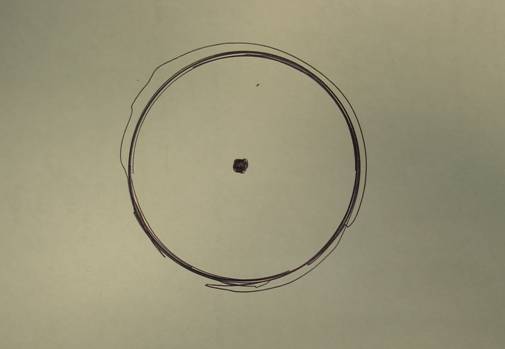

I departed alone. A geometrically pure circumnavigation of the Cathedral would look something like this. Where the dot in the middle is the Cathedral and the circle around it is my walk.

(No, the ragged line is not an attempt to emulate a Japanese enso drawing

rather it's representative of my inability to walk in a circle or draw one).

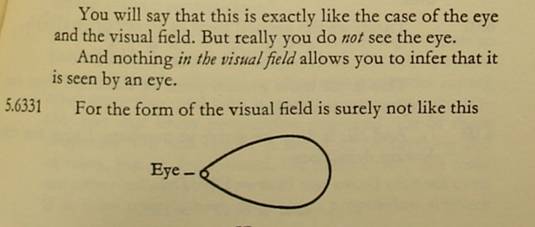

My walk, I believed, would be closer in spirit to a drawing done by Ludwig Wittgenstein, probably in the trenches of WWI as he jotted down the propositions that would form the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.

As an undergraduate, the professor of my Logical Positivism class (a man who actually understood things like Reverse Polish Notation) admitted that he didn't entirely "get" propositions 5.633 and 5.6331 so I'm sure not about to go out on a limb here and explain how it relates to Mont-St. Michel, Zen brush painting, Susan Roth, or Christ the King Cathedral.

I've just always liked these propositions for their poetry of negation and histrionic italics and I LOVE the emphatic sparseness of the artwork. In fact if I didn't have categorical imperatives around not painting on public property I'd probably use it as my personal graffiti tag.

My misuse of the above passage is as follows: let the point Wittgenstein notates as Eye represent Christ the King, and let the line which he claims does NOT delimit Eye's visual field represent my walk, which starts at the Cathedral and then ends at it.

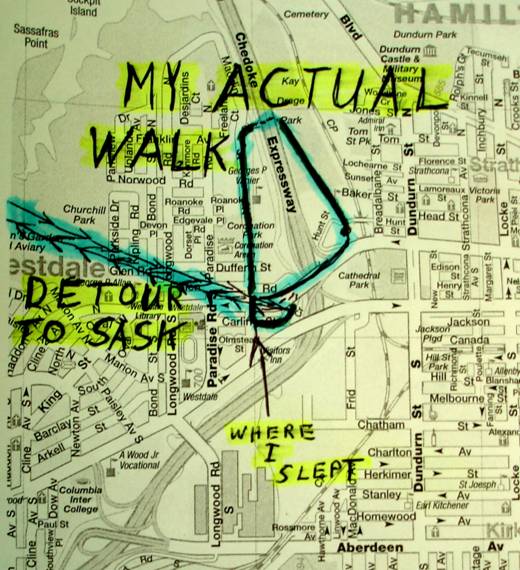

Although in actual fact my walk looked like this.

(The dotted parts are where I go under bridges, but we'll get to that.)

It was a perfect day in late fall. I passed the tower

and found a gateway into woods

and onto an open field.

I was struck here by the single white goose

which my brief reading of Hinterland Who's Who on-line suggests is a "Ross Goose" in its blue phase, as it's one of the smaller breeds of Snow goose that can be "found West of the province of Quebec" (the space that I'm working in!) and can be found "mingling with the Canada Goose."

(Or TRYING to mingle! Just look how desperately s/he wants to join in, and the snooty manner with which the dark geese turn away as though part of a club that can refuse membership based on the colour of a goose's feathers.)

The task of seeing Christ the King from various angles is, I think, reminiscent of Hokusai's 36 views of

Mount Fuji.

I crossed under the 403

and over a stream,

which made me wish I had one of those boats in Hokusai's woodcut. They seem to be seaworthy in Tsunami-like waves, so they'd obviously be fine on this water and would allow me to get some incredible shots of the Cathedral. My project at this point reminded me most of "The Anecdote of the Jar" by Wallace Stevens.

I placed a jar in Tennessee,

And round it was, upon a hill.

It made the slovenly wilderness

Surround that hill.The wilderness rose up to it,

And sprawled around, no longer wild.

The jar was round upon the ground

And tall and of a port in air.

The spire, like Steven's jar, isn't important in itself, but is a focal point that allows me to read the landscape around it.

Entering Westdale I crossed King Street and turned East onto Carling Street

which took me downwards into the valley of interstiched motor-vehicle ramps,

like copulating serpents. It was at this point that I became frustrated by how hard it was to get a looming shot of Christ the King. So dwarfed was it by the overpasses and wires that it failed to command even as much attention as a jar in Tennessee, let alone the tower of Mont St. Michel.

Was I in the wrong city? I remembered hearing that the city of Saskatoon was dominated by the Bessborough hotel, a castle-like old railway hotel placed in the dead-centre of downtown.

I am amused by novelists who, when their interest in the location they started with flags, move their cast of characters to another location, for no better reason than keeping themselves and the reader interested.

Like in Persuasion, when Jane Austen packs her characters off to Lyme Regis to visit some naval officers.

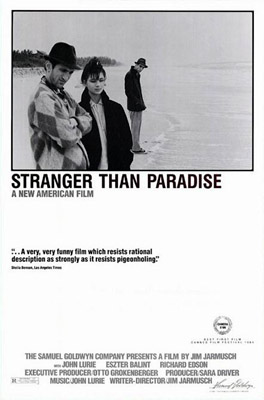

Better yet are FILMS that move the entire cast and crew to a different location for no particular reason other than it's something to do. In film, this obviously has an impact on budgeting.

Jim Jarmusch's 1984 film Stranger than Paradise springs to mind

where the three main characters travel from New York to Cleveland just because they're bored. And then from Cleveland to North Florida, for the same reason. Turns out life is equally dull in all three locations. Highly recommended. Really.

I had an idea. I reached for my cell and called Ryan McGreal

Mark: Hi Ryan. This may sound weird, but I wondered if you had any money left in the RTH budget this year.

Ryan: Oh?...um...hmmm... and why exactly are you asking?

Mark: Well it's just that I need a shot of the Bessborough Hotel in Saskatoon--So I'm looking at return airfare, and maybe two days accommodation.

Ryan: Let me just pull up the budget spreadsheet. I'll call you back.

* * *

Ryan: Yeah, no problem. We're way under-budget.

Mark: Great. I just need one shot, so I might be able to do it in a day.

Ryan: Yeah, well, whatever it takes.

I booked myself into the Bessborough, but on the second day I realized it made sense to move to accommodation across from the Bessborough so as to get an exterior photo. (A more experienced photographer might have thought of that before leaving Hamilton)

It really is quite impressive. Right in the centre of downtown. Of course there's a radical difference between Saskatoon and Mont St. Michel simply due to the fact that the Saskatchewan experience is largely horizontal, and Mont. St. Michel is about as vertical as the urban experience gets.

Back in Hamilton I picked up my walking tour where I had left off.

and I decided

to scale the bridge

from the inside

I walked to the edge of the foundation to see if there was a way up to street level, but the ascent wasn't very appealing.

Maybe it was all the traveling, but I was suddenly very tired. I must have fallen asleep.

When I awoke it was almost dark.

I looked at the surrounding residences and imaged people just home from work, or Christmas shopping, a little world behind each window, brighter and warmer than where I was.

It was strangely sad under the bridge. During the holiday season one looks for a unified sense of community, towards helping the less fortunate, or more fortunate, or equally fortunate, or differently fortunate. I thought of people who had to live in places like this, under the bridge, all year long, and how the urge to reach out to others at this time of year often just serves to remind us how isolated and fixed we are in our identities.

And as a result how limited empathy is. One is tempted to envy the metamorphoses of mythic Greek figures. Like Tiresias, who broke apart a pair of copulating serpents with his stick, and was punished for it by Hera who changed his sex and then used Tiresias to gain insight about sexual politics from one who'd been inside both experiences. And I thought of the opening lines of a poem by John Ashbery, called "And the Stars were Shining" for its fast and loose shift between radically different social strata, against a Christmas backdrop.

I first discovered this poem at 4:16 pm November 18, 1998 and I know this because it is the first thing I ever printed off the internet and the print time is at the bottom of every page. I always think of these lines in late December in the office, or when I'm aimlessly walking among street people, when I should be Christmas shopping.

It was the solstice, and it was jumping on you like a friendly dog.

The stars were still out in the field,

and the child prostitutes plied their trade,

the only happy ones, having learned how unhappiness sticks

and will not risk being traded in for a song or a balloon.

Christmas decorations were getting crumpled in offices

by staffers slumped at their video terminals,

and dismay articulated otherness in orphan asylums

where the coffee percolates eternally, and God is not light

but God, as mysterious to Himself as we are to him.

The ascent to street level was no more appealing than before, but I managed it this time.

The stars weren't shining, but with any luck streetlights would soon deploy themselves in their stead.

The bedding I passed was tempting,

as I had that grumpy and heavy fatigue I retain after any mid-day nap that lasts more than twenty minutes.

But I had dawdled enough and needed to write this thing since Ryan would want some return on financing my trip to Saskatoon. And anyway, it was the holiday season and this bed should be for someone less fortunate. Perhaps I'd bring blankets back and leave them there.

The Cathedral was lit up by now.

Exploring it one last time, I discovered a nativity scene I'd missed the earlier.

It intrigued me, because it was placed on a second floor balcony with no access to wanderers like me. The only view I could get reveled Mary, Joseph and an angel, apparently looking down at the baby Jesus but leaving him in complete mystery.

The Messiah could be any being of any tradition. Could even be a Snow Goose. In an age in which spirituality is increasingly personal and multifarious, the idea that the Messiah was invisible and left to be written by every individual appealed to me.

The spectacle of Christ the King has been overtaken by highrises and eclipsed by the anxiety of entering and exiting the 403. It does not dominate its surroundings like Mont St. Michel was designed to do by virtue of celebrating the oneness of Christianity in the 11th century.

Christ the King was consecrated in 1933 and would not particularly reflect our world if it did those things. But it has does have television screens to connect us to everything in the world.

I went back into the house and walked immediately upstairs to the view the Susan Roth again. Distances are always collapsing and the past is always returning. I arranged it at a new angle

such that its geometric relation to Mont St. Michel became near perfect.

By Susan Roth (anonymous) | Posted May 16, 2012 at 16:00:50

Thank you, Mark.

A friend sent this to me, surprised! Me too!

I would add delight and joy and surprise!

Thank you, Mark

Susan Roth sbrothpaints@gmail.com

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?