St John's Anglican Church in Ancaster has a fascinating architectural history.

By Candace Iron and Malcolm Thurlby

Published November 27, 2007

St John's Anglican Church in Ancaster has a fascinating architectural history. The present church was built after a fire had irreparably damaged its predecessor on February 27, 1868. Work on the rebuilding started in May of that year and the new church was opened May 9, 1869.

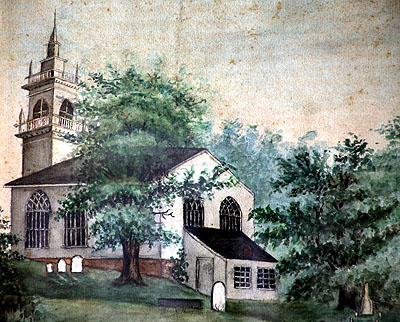

Fig. 1. Watercolour of St John's Anglican Church, Ancaster,1824, preserved in the church hall.

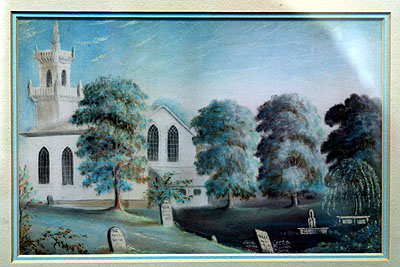

Fig. 2. Watercolour of St John's Anglican Church, Ancaster, 1824, preserved in the church archives.

It was consecrated on Thursday May 1, 1873, by Alexander Bethune, Bishop of Toronto. This church replaced the one built by Job Loder for Rev. Ralph Leeming in 1824. Fortunately the old church is known from two watercolours, one hanging in the church hall, the other preserved in the church archives (Figs 1 and 2).

Also displayed in the church hall is a remarkable set of four drawings of the present church executed by the Toronto architect, Henry Langley (1836-1907), who also designed the nave of Hamilton's Christ Church Cathedral (Raise the Hammer, May 5, 2006).

Four articles in Raise the Hammer (April 21, May 5, September 20, 2006; February 26, 2007) have introduced readers to the impressive heritage of church architecture in Hamilton, and to the significance of the Gothic style for the creation of 19th-century houses of God.

Now, in the history of St John's, Ancaster, we investigate the changing nature of the Gothic revival in Ontario church architecture between the 1820s and late 1860s.

St. John's Parish was started in 1816 upon the arrival of Reverend Ralph Leeming, a missionary priest who was sent to Canada West from England by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel to Foreign Parts. Bishop Jacob Mountain of Quebec (1750-1825) directed him to serve the area at the western end of Lake Ontario, centred in Ancaster. After his arrival he reported that the area had approximately 800 Methodists, 200 Anglicans and 200 Presbyterians.

By 1824 the church of England and of Scotland had built a 'union church', the Ancaster Free Church, on the site where the present stone structure now stands. This church had a simple rectangular plan plus a square tower at the west end which housed the main entrance (Figs 1 and 2).

The tower incorporated a balustrade which was corbelled out at the bottom of the pointed belfry openings, and was surmounted by a second balustrade and a spire. The balustrades had thin, sharply pointed pinnacles at the four corners.

In the north and south walls of the church there were either three or four large pointed windows; the tree in front of the eastern section of the south wall in the watercolours obscures this part of the church (Figs 1 and 2). The windows had a network of glazing bars which form intersecting tracery at the top.

Fig. 3. Old St Thomas Anglican Church, St Thomas (ON), exterior from S, 1824.

Fig. 4. Long Reach (NB), St James's Anglican Church, interior to E, 1841-43.

Similar windows, plain stuccoed walls and a low-pitched roof may still be seen in Old St Thomas Anglican Church, St Thomas (ON), 1824 (Fig. 3). These features are characteristic of Gothic revival churches in Ontario in the 1820s and 1830s.

The position of the two windows in the east wall of St John's implies that there was a double-decker pulpit inside the church in the centre of this wall. Such an arrangement is preserved in St James's Anglican Church, Long Reach (NB) (1841-43) (Fig. 4).

In 1826 a Presbyterian minister arrived in Ancaster, an event which made apparent the necessity for a separate Presbyterian structure. This resulted in the erection of St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church, thus leaving St John's for the Anglicans alone. St John's was consecrated by Charles Stewart, Bishop of Quebec, on October 10th, 1830.

In 1865 a chancel constructed of limestone, designed by Henry Langley, was added to the 1824 church. This provided a separate area for the altar in the medieval tradition promoted by the Ecclesiological Society and concomitantly more room for the congregation in the nave. The result would have been similar to the arrangement preserved in St James's Anglican church, Paris (ON), where in 1863, a chancel and vestry were built on to the east end of the 1840 nave (Fig. 5).

Allied remodeling is also witnessed in 1863-64 at St Mary's Anglican Church, Picton (ON), where the brick nave of 1823 was extended one bay to the east and an chancel and vestry were added beyond that, while a tower and spire were built at the west end (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5. Paris (ON), St James's Anglican Church, exterior from S.

Fig. 6. Picton (ON), St Mary's Anglican Church, exterior from S; nave 1823; chancel, vestry and tower, 1863-64.

In each case it will be noticed that the pitch of the roof in the new work is significantly steeper than in the nave. According to a parishioner's letter, the limestone chancel of St John's, Ancaster, was intended as a precursor to a future church to be made entirely of stone.

The 1868 fire provided the opportunity to rebuild the church in a more 'correct' Gothic style. This transformation to a medieval form reflected the tradition established in Ontario church building in the third quarter of the nineteenth century.

The present stone church was designed by Henry Langley who apprenticed in the Toronto office of the Scottish-trained architect, William Hay (1818-1888). Hay arrived in Toronto in 1853 having served as Clerk of Works for the English architect, George Gilbert Scott, on the Anglican Cathedral in St John's, Newfoundland.

While in St John's, Hay designed Anglican churches in Newfoundland and Labrador which received the rare distinction of a positive review in The Ecclesiologist (Raise the Hammer, May 5, 2006).

During his ten-year stay in Toronto, Hay established a thriving architectural practice. He built a large number of churches for various denominations in Ontario and penned an article entitled 'The Late Mr. Pugin and the Revival of Christian Architecture', published in the Anglo-American Magazine, II, January-July, 1853, pp. 70-73, reprinted in Geoffrey Simmins (ed.), Documents in Canadian Architecture (Peterborough, Ont: Broadview Press, 1992, pp. 44-51.

Hay's article provided a summary of Augustus Welby Pugin's True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture (1841), a book that had an immediate and profound impact on church design. Pugin insisted that proper Gothic church design could only be achieved through the careful study and reproduction of original medieval churches.

Of Hay's Anglican churches in Ontario, the best-preserved are St George's, Pickering (1856); St George's, Newcastle (1857), and St Luke's, Vienna (1861). Closer to Hamilton, his work is seen at St Andrew's Presbyterian, Guelph (1857).

In 1862 Hay left his practice to his partner, Thomas Gundry and his former pupil, Henry Langley. Langley became the leading church architect in Ontario and continued to design in the manner of William Hay especially in his Anglican churches, of which there are at least seventeen.

Fig. 8. St John's Anglican Church, Ancaster, exterior from SE.

In 1868 Langley drew the plans for St. John's Anglican Church, Ancaster. In essence, the plan conformed to the earlier church with the partially projecting west tower plus the 1865 chancel (Fig. 7).

His drawing shows the vestry to the north of the chancel and the church was erected to this plan; the room to the south of the chancel was a sensitively integrated addition (Figs 7 and 8).

The steep pitch of the roofs, the stepped buttresses at the angles of the walls and between the nave windows, the truthful exposure of the stonework, and the details of the windows are in marked contrast to the earlier church (Figs 1, 2 and 8). While the Ecclesiologists would have objected to the use of wood for the window tracery, the geometric form of the design and the proportion of the windows of the nave have English 13th-century precedent (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. St John's Anglican Church, Ancaster, nave window.

Fig. 10. St John's Anglican Church, Ancaster, west doorway.

English medieval authority is also followed for the moulded hood or label around the head of the windows and its termination on carved stops. These features are also used on the west doorway where the elaborate ironwork on the wooden doors likewise reflects medieval design (Figs 10 and 11).

The interior of St John's elaborates on the ecclesiological principles established at St Paul's, Glanford (Raise the Hammer, Feb. 26, 2007, fig. 8). In both churches the chancel is separated from the broader, taller nave by a pointed arch and the chancel floor is raised above that of the nave (Figs 11 and 12).

Fig. 12. St John's Anglican Church, Ancaster, interior to E.

There are open seats in the nave and the wooden structure of both the nave and chancel roofs is truthfully exposed. In contrast to the simple crossed-braced roof in St Paul's nave, St John's nave roof uses hammer beams (horizontal beams that project at the top of the wall) and arched braces outside which (there) are pierced BY quatrefoils.

These features, along with the paneled design of the chancel ceiling, follow English medieval models, details of which were published in Raphael Brandon and J Arthur Brandon's 1849 book entitled Open Timber Roofs of the Middle Ages.

The design of the windows at St John's is also different from St Paul's. Specifically, St Paul's has simple lancets while St John's has typologically more advanced traceried windows.

It should also be noted at St John's that a three-light window is used in the east wall of the chancel rather than the two-light windows in the nave. This emphasizes the importance of the sanctuary and provides more light above the high altar.

Fig. 13. St John's Anglican Church, Ancaster, font.

Fig. 14. St John's Anglican Church, Ancaster, old photograph of interior to E.

In accordance with the recommendations of Pugin and the Ecclesiologists, the pulpit is located to the north (left) of the chancel arch rather than against the east wall as it was in the 1824 church. The octagonal font (Fig. 13) now stands at the northeast corner of the nave but an old photograph in St John's archives shows that it was not originally in this position (Fig. 14).

It is most likely that it was formerly placed at the west end of the nave next to the main entrance to the church as at St Paul's, Glanford. The old photograph is also instructive on the former painted decoration of the walls and the location of the organ. Moreover, it shows the window in the centre of the south wall of the chancel prior to the addition of the room there (Figs 8 and 14).

Henry Langley succeeded in providing the congregation of St John's with an ecclesiologically correct Gothic church based on medieval design principles.

It is markedly different from its predecessor in all matters of detail. Furthermore, it stood in sharp contrast to the Wesleyan Methodist Church erected across the road in 1869 (Fig. 15). With the exception of the steeply pitched roof, the Methodist church conformed to an 18th-early 19th-century design tradition.

The simple rectangular plan was well suited to the preaching requirements of the Methodists. They did not need a separate chancel for a high altar and they eschewed medieval-inspired window design and stepped buttresses. For the Anglicans all such medieval architectural references served as essential reminders of the churches in mother England and boldly proclaimed the heritage of their church.

Fig. 15. Wesleyan Methodist (now part of Ryerson United) Church, Ancaster, 1869.

By parishioner d (anonymous) | Posted December 22, 2007 at 21:58:09

I am currently a parishioner at St. John's Ancaster and enjoyed reading the article. Rev. Cannon Philip Jefferson had a huge influence in bringing together the archives and creating a new Archive Room in which everything is housed. We're very proud of our church. Come visit Sunday @ 10:00 a.m. sometime!

By gigib (anonymous) | Posted February 13, 2008 at 14:36:47

Hello,

What a fascinating article. I was thrilled to find this on line. How can I get help in locating baptism and death records from the church? My Kelly line was briefly in Ancaster and they were Wesleyan Methodist. They were there between 1851 and 1858.

Thank you and God Bless

GiGi

snoopy8u@yahoo.com

By max843 (anonymous) | Posted December 01, 2010 at 14:19:48

Lovely article. My great-great-great-uncle was the second rector of St. John's, the Rev. John Miller from Longford, Ireland.

After his graduation from Trinity College Dublin, his parents immigrated to Quebec City with their six children. He and his wife Carolyn as well as his brother, Dr. James Miller, are buried in the Churchyard.

How surprised Uncle John would be to see the new church and how the countryside has changed!

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?