The only thing I think I can state with any confidence is that anyone who thinks things will go back to normal in a couple of weeks does not understand the gravity of the situation we're in.

By Ryan McGreal

Published March 19, 2020

It seems to me that one of the defining characteristics of the COVID-19 pandemic is the disorientating sensation of desperately trying to catch up to a situation that keeps accelerating away from us.

As recently as couple of weeks ago, the novel coronavirus still seemed like an international news curiosity, something happening to someone else. Then on March 11, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global pandemic, and things started to happen very quickly.

On March 12, Sophie Gregoire Trudeau, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's wife, tested positive for COVID-19 and both of them went into isolation. For many Canadians, this is the point at which the crisis started to become real.

On March 15, Dr. Theresa Tam, Canada's chief public health officer, urged Canadians returning from abroad to self-quarantine and implored everyone to practice "social distancing" in order to "flatten the curve" of disease transmission - phrases that were suddenly everywhere in our discourse. We learned that 30-70 percent of Canadians can expect to be infected at some point.

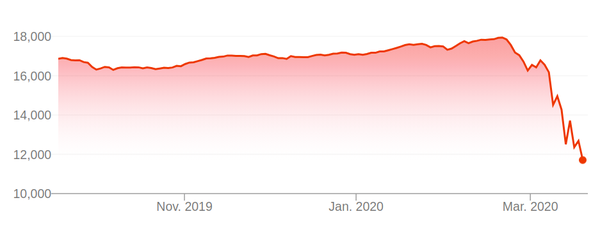

Investors were the first to panic, triggering the sharpest stock market decline since the Great Depression. Within a couple of weeks, the S&P/TSX composite index plummeted 6,000 points.

S&P/TSK Composite Index, 6 months

In the following days, Prime Minister Trudeau issued a consecutive series of announcements that were increasingly extraordinary and unprecedented. On March 16, he closed the border to people from most countries (though inexplicably leaving an exception for the USA) and refusing to allow anyone with COVID-19 symptoms to board a flight to Canada. On March 17, he also closed the American border and announced an $82 billion emergency aid package to ensure Canadians don't lose their homes or starve.

On March 12, Ontario Premier Doug Ford announced that schools would remain closed for an additional two weeks after March Break to try and slow the rate of infections. This serious move, urged by public health experts, seemed to shock Ontarians out of their reverie.

People began panic-buying provisions, and grocery stores were quickly stripped of hand sanitizer, disinfecting wipes, dried and canned goods and toilet paper. Hostilities began breaking out among frustrated, scared customers fighting over dwindling supplies.

Toilet paper aisle at a Hamilton grocery store

Flour aisle at a Hamilton grocery store

In the following days, Ford reversed his government's austerity agenda, restoring labour protections for sick leave that he had previously eliminated and announcing financial support for affected individuals and businesses.

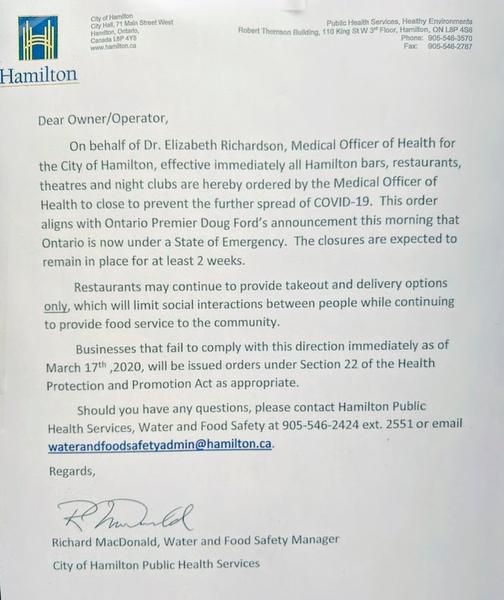

On March 17, as Trudeau was closing the national border, Ford declared a state of emergency in Ontario, ordering the immediate closure of all restaurants, bars, theatres, arenas, recreation centres and libraries and banning congregations of more than 50 people.

All restaurants have been ordered closed

Amidst this whirlwind of escalating policy steps, public events of all kinds were being postponed or cancelled, from neighbourhood association meetings to concerts to Jane's Walk Hamilton, the Around the Bay Road Race and everything in between. Employers announced that they would be urging as many employees as possible to work from home.

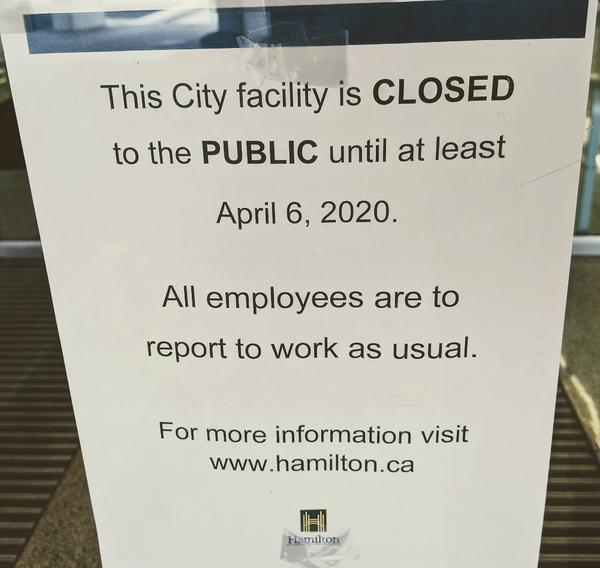

On March 16, the City of Hamilton suspended most of its public programs, closing libraries and rec centres and even City Hall to the public. The HSR reduced transit service levels, similar to the TTC in Toronto and Metrolinx regional transit.

Dundurn Castle closed until April 6 or until further notice

On March 18, in a bid to protect HSR drivers from exposure, the City announced a new policy to load and unload transit passengers via the rear doors, waiving fares altogether.

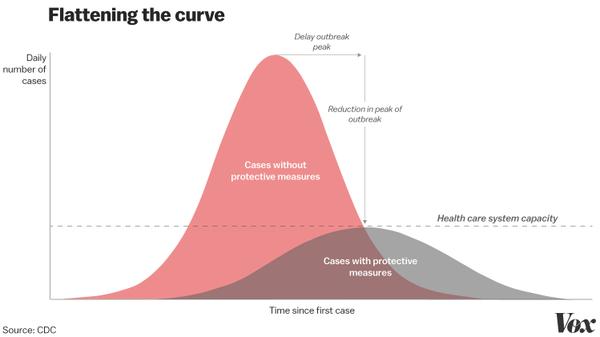

In just a matter of days, Canada has careened from going about its merry business to practically shutting down in a desperate bid to "flatten the curve". This important term deserves some explanation.

Compared to influenza, COVID-19 has a long incubation period before symptoms appear. The median is 5 days and can be as long as 14 days, and it is contagious during incubation. It has a basic reproduction rate (R0, pronounced "R-nought") of between 2 and 3, meaning each person who contracts the virus will infect an average of 2 or 3 other people. (And each of those people will infect an average of 2 or 3 people.) At this rate, the number of infected people follows an exponential growth curve.

It can be hard to conceptualize what exponential growth actually looks like, but a case study may help. Italy took a business-as-usual approach early on, and in three short weeks that country went from just three confirmed cases to over 15,000 on March 12 and over 35,000 by March 18. The death toll stands at 3,000 as I write this. The country is under lockdown and the health care system is utterly overwhelmed. Exhausted doctors with no spare capacity are being forced to decide who to save and who to let die.

When public health experts talk about "social distancing", they mean systematically reducing the number of interactions between people that could lead to virus transmission. The goal is to slow down the rate of transmission to the point where it doesn't accelerate expoentially out of control - to "flatten the curve" of infections growth.

If the total number of cases increases at a slow enough rate, the number of serious infections at any given time will remain low enough that hospitals can provide intensive care to everyone who needs it.

Graph: flattening the curve (Image Credit: Vox)

COVID-19 appears to have an overall mortality rate of around 2 to 3 percent, with a higher rate among patients who are older and who have other health conditions and weakened immune systems. However, it is a mistake to assume young people are somehow safe from serious complications. People at any age can experience serious symptoms that require medical intervention.

The numbers seem to vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, but somewhere between 5 and 20 percent of people who contract COVID-19 require hospitalization. Around one-third of those people require intensive care. If too many people get sick at the same time, there simply won't be enough beds, enough ventilators, enough health care providers to meet the need.

Hence the increasingly extreme measures undertaken by Canadian leaders to try and flatten the curve so we don't end up like Italy.

Unfortunately, thanks to decades of neoliberal policy that has steadily starved our public services, Canada has only around 2.5 hospital beds per thousand residents. That's only half the WHO's recommended hospital capacity under normal circumstances - and our current circumstances are anything but normal. All in all, Canada has around 57,000 hospital beds - but that's the total, not our spare capacity.

In Ontario it's even worse: we have only around 18,000 hospital beds in total, or just 2.3 beds per thousand residents. (If we take nothing else from this crisis, we should burn into our brains the fact that decades of tax cuts and austerity have left us dangerously unprepared for a crisis.)

Hence the urgency of social distancing and flattening the curve. We simply don't have the spare capacity in our medical system to absorb an explosion of severe infections.

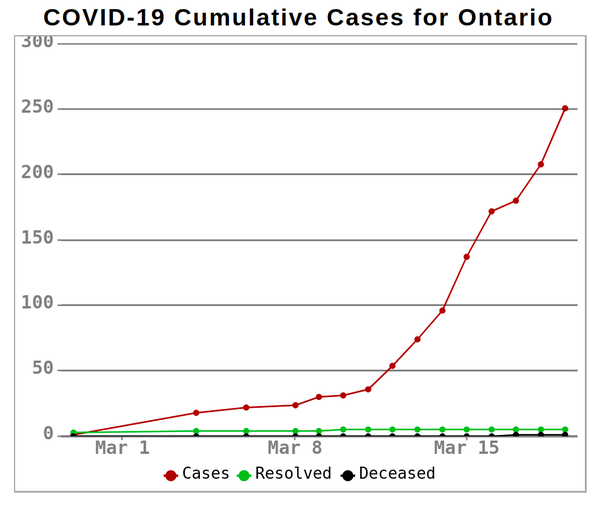

I've been tracking the cumulative number of COVID-19 cases in Ontario since the end of February. The (relatively) good news, based on my very amateur assessment, is that it's not actually clear whether the increase in cases is following an exponential growth curve.

Chart: Total COVID-19 Cases in Ontario, February 28 - March 19

At the risk of getting technical, one way to recognize an exponential curve from the data is to calculate the difference between subsequent values in the set. If the size of the difference keeps increasing from one day to the next, that looks like an exponential function.

For example, the case total was 30 on March 9 and 31 on March 10, so the difference was 1. The total increased to 36 on March 11, for a difference of 5. Then it increased to 54 on March 12, for a difference of 18. The size of the difference kept increasing: to 20 on March 13, 22 on March 14 and 41 on March 15.

So far, that's looking pretty exponential. Keep extrapolating forward with bigger and bigger daily increases and you're quickly into thousands of cases, then tens of thousands and then hundreds of thousands.

But then things changed on March 16. The case total increased from 137 to 172, for a difference of 35. That increase of 35 is smaller than the previous day's increase of 41 (from 96 to 137).

On March 17, the total cases increased from 172 to 180, for a difference of just 8. March 18, the total increased from 180 to 208, for a difference of 28. And on March 19 (as I write this), the total has increased from 208 to 251, for a difference of 41 again.

Based on this, I can't predict whether tomorrow's case total will increase by 10 or 20 or 50 or 100. There's no clear pattern. It's still too early to state that this means distancing is working, but at least the numbers aren't screaming at us that it's failing. So that's something.

I can just imagine how surreal our leaders must have felt these past several days, hearing the astonishing words coming out of their own mouths: all schools closed, state of emergency, closed borders, major disaster relief. They're scrambling to catch up to the moving target of this crisis while we scramble to catch up to the moving target of their response.

Is it enough? I honestly don't know. But I can't shake the feeling that each day, our leaders have announced the measures they should have announced the day before. To use a Canadian analogy, it feels like they keep skating to where the puck was instead of where it's going to be.

For example, why wait an extra day to close the American border? After all, America's caseload is following a classic Italian-style exponential growth curve. Perhaps closing the world's longest undefended border was just unimaginable until it became unavoidable.

What is still to come? Will Trudeau have to declare martial law and put the entire country under lockdown? Is such a thing even imaginable? Yet French President Emmanuel Macron just did exactly that earlier this week. Was it the right choice? No one really knows yet.

Canada has closed its external borders, but if it becomes necesssary to close our internal borders as well, that will require Parliament to resume with a quorum of MPs and Senators who vote to invoke the Emergencies Act.

The only thing I think I can state with any confidence is that anyone who thinks things will go back to normal the second week of April, when the additional two weeks of school closure run out, does not understand the gravity of the situation we're in.

City Hall closed until at least April 6

Assuming social distancing, locked-down borders, enhanced sanitation, diligent hand-washing (seriously, wash your hands: 20 seconds of vigorous lathering and rubbing with soap and water kills the virus), no face-touching, no public events and so on are enough to flatten the curve, we are going to have to maintain those practices until there is a vaccine that innoculates us against every active strain, and a protocol of medical interventions that are effective at keeping people alive when they come down with severe symptoms.

If we abandon these protocols before a vaccine is ready, we fall right back into exponential growth again. Realistically, we are looking at 18-24 months before a vaccine is ready. That means we are going to have to get used to this new normal.

Will we be willing to accept month after month of isolation? Will our economy be able to accommodate the massive reduction in economic activity this must necessarily entail without collapsing? Will our manufacturing and distribution systems, currently built on global supply chains and just-in-time logistics, be able to adapt?

I don't think anybody really knows the answers to these questions, at least not yet. We're going to have to try and figure them out together.

By jnyyz (registered) - website | Posted March 19, 2020 at 15:59:12

if you plot the #cases on a semi log plot, it is roughly linear, i.e. the growth is exponential. It will take at least two weeks more data to see if social distancing is affecting the trend, given the long incubation period for the virus.

By Angelune (registered) | Posted March 19, 2020 at 16:54:53

I don’t think we can calculate the rate of transmission until the majority of new cases are due to community transmission rather than imported through travel. In addition, there aren’t enough data points to determine much yet.

By ENBertussi (registered) - website | Posted March 20, 2020 at 02:43:58

from what i understand the lag time of tests is 4-6 days so we're always looking at over half of and almost an entire full week ago's data set.

By Ryan (registered) | Posted March 20, 2020 at 16:07:40 in reply to Comment 130554

If you click through to my COVID-19 cases page and scroll down to the table, you can also see the backlog of tests awaiting results is getting bigger and bigger. If we assume the percentage of cases that come back positive is the same for the backlog as it is for the returned tests, that would mean there are actually 419 presumptive cases as of today (March 20), rather than 301 based on the returned test results.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?