There are three challenges that face transit expansion in Hamilton that are each defeating and together fatal: project timelines, area rating, and an abject failure of political leadership.

By Sean Hurley

Published January 05, 2020

CBC Hamilton reporter Samantha Craggs wrote an article on the possibilty of bus rapid transit (BRT) in Hamilton, in which she asked: "will BRT have its time?"

BRT won't have its time. Don't bet on Just More Buses (JMB) either.

There are three challenges that face transit expansion in Hamilton that are each defeating and together fatal. They are: (1) project timelines, (2) area rating, and (3) an abject failure of political leadership.

We know it would take a minimum of seven years to build A-Line BRT, assuming there were no bumps along the road, once all the planning decisions are made.

And that is highly optimistic. Active planning for Hamilton's B-Line light rail transit (LRT) line began in 2007 and a funding commitment was not announced until nine years later, in 2015.

Even if those timelines could be cut in half, the reality remains that there will be no shovels in the ground prior to provincial and municipal elections in 2022. Should Ontario and Hamilton voters each or separately sweep the slate clean, chances are, just like now, we will be starting all over again.

Nevertheless, Craggs reports in her article that Ward 9 Councillor Brad Clark "would opt for two BRT lines: one across the lower city and one on the Mountain." That is almost the plan that was to be implemented from 2015, which provided for B-Line LRT and A-Line BRT.

Clark told Craggs, "he'd also like to see more buses running along the BLAST network, which is a series of city-wide routes designated for rapid transit." Craggs helpfully points out that B-line LRT "was the first stage of that" network.

When Clark challenged Fred Eisenberger for the Mayor's office in 2014, he ran against LRT and in favour of BRT. He avoided defining his vision of BRT until near the end of the campaign, but eventually conceded that when he says "BRT" he means "express buses".

Indeed, he told Craggs: "We could put in right across the city bus rapid transit, express routes", as though they're the same thing. They're not. One is rapid transit and the other is buses in mixed traffic that makes fewer stops.

Let us be generous and accept in good faith the councillor's vision of JMB and even look to the example of Brampton. Brampton has implemented an express bus network that has some characteristics of BRT, like traffic signal priority and all-door boarding.

Brampton has grown its transit ridership, breaking with the general trend of stagnant or declining ridership, and their ZÜM express bus service appears to be the driving force. So it could work, but not in Hamilton and the reason is area rating.

In the 2018 municipal election, Clark backed mayoralty challenger Vito Sgro, who also ran against building LRT. Like Clark, Sgro proposed JMB with what he called "express routes".

What Sgro, Clark and some other members on council were promising was more transit for the suburban wards. However, the other aspect of their transit plan is "to keep the existing area-rating tax policy for transit".

During his mayoralty campaign, Sgro wouldn't say how he would fund JMB that "would extend from Fifty Point in Winona to Waterdown, from Mount Hope to the water" with area rating in place.

What is area rating? In 2001, as part of the amalgamation of Hamilton with its five neighbouring suburban municipalities, HSR taxes were rated according to the level of service received in suburban wards prior to amalgamation.

This was supposed to be a temporary measure but it has become permanent. What it means is that residents in the old city of Hamilton pay as much as three times more in taxes for HSR than do residents in the amalgamated suburbs. Expanding HSR to Fifty Point, Waterdown, and Mount Hope necessarily means raising taxes on residents in those wards, which the same politicians making the promises refuse to do.

The proposed LRT was to be designed, built, financed, operated and maintained by a private operator, meaning the tax levy would not be required to provide service. That is why it was possible. In any scenario where HSR operated BRT or JMB, especially on routes that serve suburban areas, local property taxes must go up to pay for it.

That is why Clark will not say how he would finance expanded HSR operations.

Like Clark, Ward 15 councillor Judi Partridge opposed LRT, and she too "wants any solution to include the whole city, even rural areas like the ones in her ward."

Partridge has no objection to residents of the lower city contributing to a highway by-pass that only benefits residents of Waterdown who commute to the GTA, but she opposes provincial investment for transit in the core.

Meanwhile, Partridge also opposes eliminating area rating for transit, making her claims to want transit for the "whole city" empty rhetoric.

Thanks in part to the legacy of area rating, the last major advance in public transit in Hamilton precedes amalgamation and that was the development of BLAST and the implementation of the B-Line Express Bus as a first step toward frequent, rapid mass transit - way, way back in 1986.

The stunted BLAST network followed on the heels of Hamilton turning down the provincial gift of what later became the very successful Vancouver SkyTrain back in 1981.

Ultimately, the failure to build transit in Hamilton is a failure of leadership. Doug Lychak, who was the regional planning and development manager championing the ill-fated rapid transit project in 1981, sums up the problem succinctly: "If Hamilton has lacked anything in the past, it's the ability to see strategically and think strategically".

In almost 40 years, little has changed.

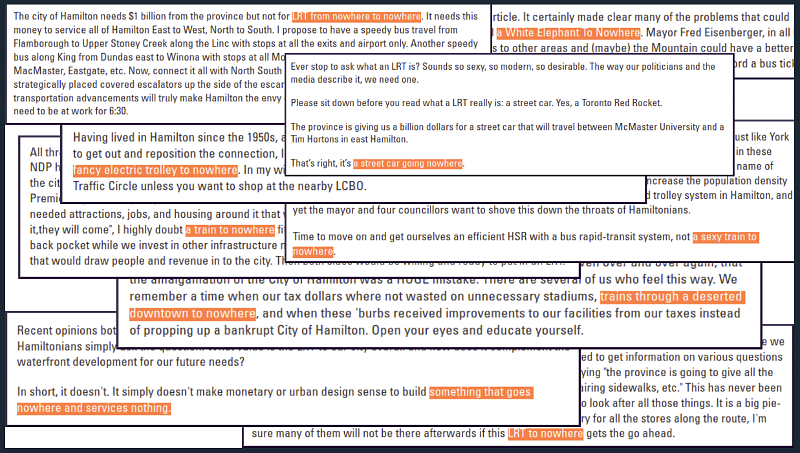

People will oppose transit for any number of contradictory reasons. In 1981, Limeridge and Jackson Square ]were considered "nowhere"](/article/3021/alegacyofmissedopportunity:thehamiltonrapidtransitplansthatcouldhave_been). Today, "nowhere" is everywhere from Eastgate to McMaster.

Recurring theme in anti-LRT arguments

In 1981, detractors opposed a grade-separated transit system and today they oppose a surface transit system. There will never be a consensus among Hamiltonians - that is where planning and leadership come into play. And leadership has failed Hamilton every single time.

Take a moment to think of the world we live in today. We are confronted by the looming and potentially catastrophic crisis of climate change and we are challenged by the emerging technologies of electrification and automation. These realities will shape how people move around cities and the affordability of doing so.

Public transit is the great equalizer that will bridge disparate technologies and modes to ensure everyone can get to where they need to be. But Hamilton is more than a generation behind in that investment [PDF].

In another 25 years, do people want to live in a Hamilton unchanged from today? Because that is the "strategy" of the council leadership we have had to endure since amalgamation.

This should be particularly alarming for those concerned about social justice and housing. The Hamilton for which Ontario Transportation Minister Caroline Mulroney is preparing for us, along with council members like Clark and Partridge, is a Hamilton that is a bedroom community for the GTA, which is projected to add another four million people to the current ten million within 25 years.

Sacrificing local transit to build highways and regional transit serves only commuters seeking less expensive housing in Hamilton and beyond. The LRT project primarily serves people who live and work in Hamilton.

There will never be progress through a process of developing plans over many years, investing time, energy, and tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars, and then brushing it all away to start over again. What can we do?

Add your voice to the many demanding Premier Doug Ford reverse Mulroney's decision.

Alternatively, demand that council freeze the current plan and do all that can be done to prevent Metrolinx from unloading properties acquired for LRT.

At the same time, plan to elect a new provincial government and council in 2022 to get LRT back on track and to once and for all end area rating. Two years late is better than yet another generation behind.

By Haveacow (registered) | Posted January 06, 2020 at 18:26:10

Before the City of Gatineau built and opened its Rapibus BRT System in 2013, from Tache Station in the Hull Sector (the old City of Hull, Quebec), towards Labrosse Station in eastern Gatineau, a distance of 12 km, critics called most of the line's 10 station locations, nowhere as well!

Their bus operator the STO (Societe de transport de l'Outaouais), credits the Rapibus as the reason why their ridership continues to increase. They were the first adopter in Canada of transit fare cards way back in 1998 and credit them as one of main reasons for their success. In 1992, the STO moved 2.5 million passengers a year. The total for 2019 is thought to be around 22 million. For a city of 350,000 that's a lot of rides from nowhere to nowhere.

Announced in 2018, the STO has approved in principal a surface LRT line (similar to Hamilton's former B-Line LRT) to the western Alymer Sector (Former City of Aylmer, Quebec) to the Hull Sector across the river to downtown Ottawa and a branch to a north-western neighborhood "the Platreau". This 26-28 km line will cost approximately $2.2 Billion. The line is planned to open in 2028. Critics again call this an LRT line from nowhere to nowhere.

June 2019, the Quebec provincial government pledged 65% of the line's costs, if the Federal Government pays the rest. A lot of money for a line from nowhere to nowhere but they seem to want to fund it. The federal government is supportive of the project. I see even more future transit rides in Gatineau from nowhere to nowhere, somewhere around 2028.

By Clyde_Cope (registered) | Posted January 07, 2020 at 06:36:02

Given the latest news reported by the "Star" that companies bidding for the Hamilton LRT had quit bidding months ago. How much did the Hamilton Mayor know about this and when? I smell a skunk!

By Blotto (registered) | Posted January 07, 2020 at 09:44:03

Can we save the $1 Billion for the payouts for the upcoming class action lawsuit(s) for Red Hill and Chedoke Creek?

By KevinLove (registered) | Posted January 14, 2020 at 18:50:46

Here is a video about real BRT in Bogota, Columbia. See:

By ergopepsi (registered) | Posted January 20, 2020 at 21:58:40

If we can't have LRT maybe we should consider BRT as long as it still has the dedicated corridor and proper stations. It is cheaper to build and to be honest I think we may be in a situation where beggars can't be choosers. If BRT fits in the budget then why not? It is a compromise that some councilors who've rejected LRT have said they would support (Clark for one). The Montreal subway is essentially an underground BRT and it is a pretty soft and quiet ride.

By Ryan (registered) | Posted January 21, 2020 at 13:45:56 in reply to Comment 130501

It's cheaper to build (but not a lot cheaper), but about twice as expensive to operate per passenger. In any case, BRT has never been a serious alternative rapid transit system. All the things LRT opponents hate about LRT - dedicated travel lanes, investing across the lower city, improving transit - are equally true of BRT. Anti-LRT politicians like Clark who advocate "BRT" as an alternative don't actually support BRT either. When you press them for details, what they're really advocating is Just More Buses (JMB). It's a trap, not a real proposal.

By Haveacow (registered) | Posted January 22, 2020 at 13:08:11

What Ryan is talking about is the non-transit supporter whom likes BRT or a "Political BRT" as opposed to real BRT. Politicians who are desperately supporting BRT over LRT, just want an Express Bus with really nice bus stops most likely, operating in mixed traffic with a few km's of nearly useless painted bus lanes. Brampton's Zuum Bus Rapid Transit Network comes to mind. Yes, it can build up the numbers of passengers but it offers very little real time savings especially, if vehicular traffic becomes heavy along the route. Painted Bus lanes on busy streets are almost impossible to monitor and prevent non-bus vehicle access to the bus lanes.

Real BRT costs quite a bit and has real traffic free rapid transit operations and stations. York Region's Viva BRT comes to mind. A real political commitment to actual BRT operations is a must. The phrase, "Like a train line but with buses" should never be said more than once by the operations staff of your future BRT system. Real BRT systems don't operate like that at all, they just look like they do.

Real BRT has physically segregated lanes that required years construction and network designs that think about future capacity needs. Like having or leaving space for passing lanes at stations, wide dump areas for snow and water removal. Having or planning for, completely private segregated Busway right of ways (like Ottawa's or Mississauga's Bus Transitways) with expandable real, rapid transit like stations. Stations with different passenger platforms areas for transfers between local buses and busway buses (mostly closed busway operations) and or rights of wwys that allow for entrances and exits to and from the busway for local buses to access the busway. This gives the possibility of local bus services that can instantly become busway services which provides single seat destination service over longer distances (mostly open busway operations). Finally a design which has a realistic operating limit in mind and allows for conversion to another mode of rapid transit in the future, like LRT.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?