With careful analysis of several details of the church, it is possible to make a good case for an attribution to John Turner (1807-1887).

By Malcolm Thurlby

Published October 25, 2018

At 2:00 PM on Sunday, October 14, 2018, a service was held at St Paul's Anglican Church, Middleport to celebrate its 150th anniversary. The church was packed. The service included recollections of a number of long-term congregants, a moving experience which highlighted the significance of this church in their lives.

For me the event conjured up different emotions. I first came across St Paul's in the late 1980s after moving to Brantford in 1987. As an architectural historian born in London, England, and trained as a medievalist, I was thrilled to find this gem of board-and-batten Gothic architecture, a brilliant adaptation of English medieval models, and a rare and precious survival from 1868 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Middleport, St Paul's Anglican Church, exterior from (liturgical) SW.

In an earlier article on the church in Raise the Hammer I discussed St Paul's, Middleport in the context 19th-century Gothic architecture

Reference was made to the churches of Frank Wills (1822-1857) who apprenticed with John Hayward, the leading architect in Exeter (Devon), and moved to Fredericton with John Medley, who was appointed Bishop of Fredericton in 1845. Wills designed the Gothic cathedral and St Anne's Chapel in the city and other churches in the diocese.

Wills moved to New York in 1848 and, in 1850, published his influential book titled Ancient English Ecclesiastical Architecture and its Principles Applied to the Wants at the Present Day. He designed board-and-batten Gothic churches including one - long since demolished - at St Mary's, Cainsville, just east of Brantford, which may have influenced the design of our Middleport church.

Another important figure for Gothic revival churches was Scottish-born architect William Hay (1822-1888), who sailed to St John's, Newfoundland in 1847 to become Clerk of Works for George Gilbert Scott's Anglican Cathedral. He designed a number of board-and-batten churches. Based in Toronto from 1854 until 1862, he established a thriving practice and designed Grace Anglican Church, Brantford, where the supervising architect was the local practitioner, John Turner (1807-1887).

In my 2010 article, I suggested that "the use of board and batten at St Paul's, Middleport may be derived from William Hay through John Turner, and it is possible that Turner himself was the architect." At the current state of research, no documentation has come to light about the architect of the Middleport church. This state of affairs is not unusual for 19th-century buildings. Nevertheless, with careful analysis of several details of the church, it is possible to make a good case for an attribution to Turner.

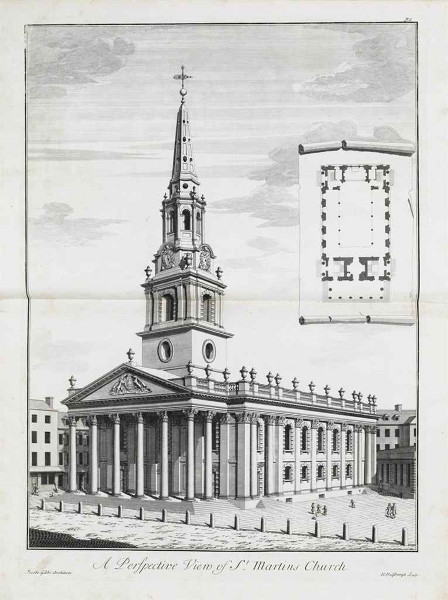

Fig. 2. London, St Martin-in-the-Fields, exterior from SW, from James Gibbs, Book of Architecture (1728)

One motif of St Paul's tower, the roundels in the second storey, may be regarded as old-fashioned in that it seems to belong to a 17th- and 18th-century tradition established in the London City churches of Christopher Wren (1632-1723) and followed in the churches of the Scottish born architect James Gibbs (1682-1754), as in his famous London church of St Martin-in-the-Fields (1721-26) (Figs 1 and 2).

James Gibbs' Book of Architecture, published in 1728, was immensely influential throughout the English-speaking world. His Marylebone Chapel (St Peter's Vere Street), London (1721-24), was illustrated in his book and served as a model for St Paul's Anglican Church, Halifax, Nova Scotia, commenced in 1749. Holy Trinity Anglican Cathedral in Quebec City, 1800-1804, was based on St Martin-in-the-Fields. At this time and down to the 1830s, the Gibbsian model provided the 'correct' form for the Church of England worldwide. Roundels could be used for windows, ventilation or belfry openings. A late example can be seen at Christ Church, Vittoria of 1845 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Vittoria, ON, Christ Church Anglican (1845), exterior from W.

Yet apart from this one motif, St Paul's, Middleport is different from the Wren/Gibbs tradition. Most obviously, pointed arches replace the round-headed arch. Gothic replaces the classical tradition. As I discussed in my original article, by the 1860s Gothic was the 'correct' style for the Church of England, and the elements at Middleport indicate that the designer was well versed in the this vocabulary.

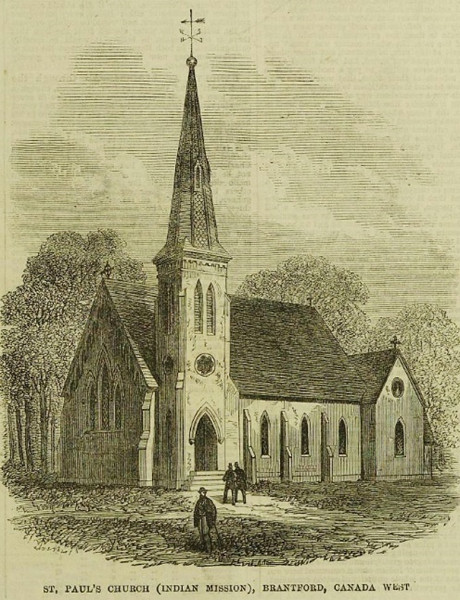

We need to search for churches which combine roundels in towers with pointed arches. Such roundels are far from common in Gothic revival a churches. However, they do occur in the work of John Turner, as at St Paul's Indian Mission Church, 1187 Sour Springs Road/2nd Line, designed in 1866 (Figs 4 and 5).

Fig. 4. St Paul's Anglican Church, Sour Springs, from The Illustrated London News, 2 Feb. 1867, 113.

Fig. 5. St Paul's Anglican Church, Sour Springs, exterior from SW

The church holds the rare distinction of having been published in the Illustrated London News [London, England], 2 Feb. 1867, 113) (Fig. 4). Here and in the accompanying recent photo (Fig. 5), we see the single lancet window on the side wall of the tower with a roundel above and the paired lancets for the belfry in the top storey surmounted by the spire. The association with St Paul's, Middleport is obvious. And, the relationship does not end there. Both churches have single lancet windows in the side walls of the nave, and triple stepped lancets in the east wall of the chancel (Figs 1, 4-7).

The details of the (liturgical) east wall of the chancel are especially relevant. The triple stepped lancets are popular in the east walls of small Anglican churches and are strongly advocated by the Ecclesiologists as a reference to the Trinity. At Sour Springs and Middleport the sills of the lancets are set relatively high in the wall, while the heads of the windows rise well into the gable (Figs 6 and 7).

Fig. 6. Middleport, St Paul's Anglican Church, exterior from (liturgical) SE.

Fig. 7. St Paul's Anglican Church, Sour Springs, exterior from E.

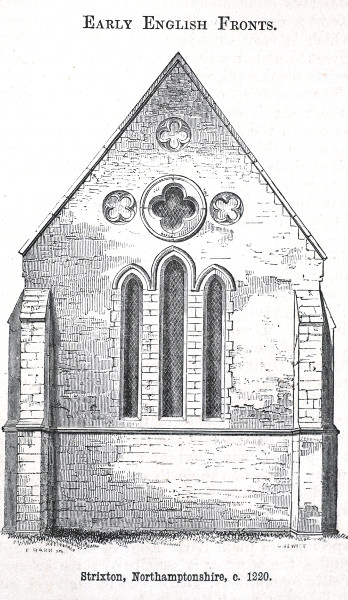

Such proportioning is in contrast to William Hay's handling of the motif as in St Luke's, Vienna ON (Fig. 8) and in the majority of Early English Gothic small churches of the 13th century, such as St Romwold's, Strixton (Fig. 9), which was published in 1849 (Edward Barr, Elevations, Sections, and Details of Strixton Church, Northamptonshire). These comparisons and contrasts speak strongly in favour of the attribution of St Paul's, Middleport to John Turner. Finally, the doorway to the vestry at Middleport is an unusual feature yet is paralleled in both vestries at Sour Springs (Figs 7 and 10).

Fig. 8. Vienna, ON, St Luke's Anglican Church, William Hay, 1860-1862, exterior from NE

Fig. 9. Strixton (Northamptonshire), exterior from E.

Fig. 10. Middleport, St Paul's Anglican Church, exterior from (liturgical) NE.

Returning to the design of the Middleport tower, it should be noted that John Turner's North Ward Methodist Church, Brantford (1870-1871) (later Brant Avenue Wesleyan Methodist, subsequently Brant Avenue United, and now converted to a condominium) includes the roundel motif plus paired belfry lancets and a spire like Middleport (fig. 11).

Turner also incorporated the ground-floor lancet window, second-storey roundel and paired belfry lancets in his Onondaga School House number 6 (1876) (Fig. 12), which was so tragically demolished in August of this year, an act of vandalism for which the Brant County councillors should be truly ashamed.

Fig. 11. Brantford, former Brant Avenue Wesleyan Methodist Church, John Turner, 1870-1871), exterior from (liturgical NW.

Fig. 12. Onondaga, ON, School House number 6, John Turner, 1876, now demolished.

Comparisons between St Paul's Middleport and churches of Brantford architect John Turner strongly suggest that Turner was the designer of Middleport. To my knowledge, the juxtaposition of the motifs discussed is not found in the work of any other Canadian architects. The result is a splendid adaptation of the vocabulary he used in his brick churches and school house to the board and batten of the rural church.

It remains for me to thank Robert Hill for his wonderful Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada 1800-1950, which provides researchers with invaluable references to documented work, including John Turner. It is available online.

By dalcide (registered) | Posted October 28, 2018 at 12:09:09

I think that your reasoning is sound and you make a very convincing case for the attribution to John Turner. As always, your photos help to clarify your observations. I also applaud your strong language in disparaging the Brant City Council's decision to demolish a beautiful historic building. Surely another solution could have been found to incorporate the historic into the contemporary building. It is a shame that institutions such as the Ontario Heritage Trust do not have more power to veto such demolitions, as I am sure they would have.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?