The city's broadcast policy for quasi-judicial tribunals should be clear, it should be consistent, it should strike a reasonable balance between competing rights, and it should be applied fairly and consistently.

By Ryan McGreal

Published March 10, 2017

Well, it has been an interesting week for administrative policy in the City of Hamilton, as a controversy has erupted over the ejection of a journalist from a public meeting at City Hall.

First of all, the basic facts.

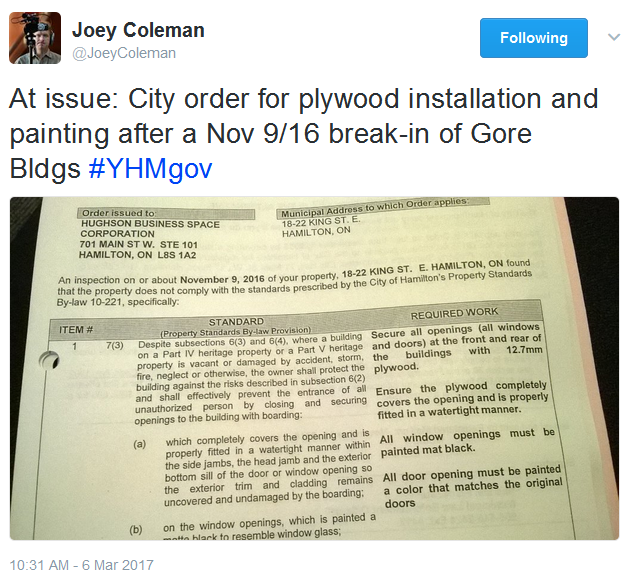

The Property Standards Committee held a hearing on March 7, 2017 on a work order issued to the owner of 18-22 King Street East requiring the building owner to secure the building's openings, which the owner was appealing. The Public Record journalist Joey Coleman attended the Property Standards Committee meeting on March 7, 2017, arriving after the meeting had begun. After sitting down, Coleman tweeted two images: a photo of the committee with a note about the agenda, and a detail of the work order itself.

Tweet from Joey Coleman, March 6, 2017

Tweet from Joey Coleman, March 6, 2017

A City representative asked if Coleman was "broadcasting" and "recording" the meeting. Coleman ignored the question. (He later asserted that it was made "in an aggressive confrontational manner.") When the question was repeated, Coleman cited Section 2(b) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which states:

- Everyone has the following fundamental freedoms:

[...]

(b) freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication;

The Clerk stated that Coleman had to request permission to broadcast at the start of the meeting, and that he was in violation of the City's policy. The meeting Chair asked the appellant if he objected to being recorded, and the appellant said he did object.

The hearing was suspended and the room was cleared so the committee could discuss the matter. When they reconvened, they demanded that Coleman turn off his phone (Coleman says they told him to remove the battery). Coleman refused, arguing that he was engaging in Charter-protected journalism.

At this point, Coleman was ordered to leave the room. He refused to leave, and the City lawyer advised the committee to adjourn and reschedule the meeting. Not wanting to see the meeting cancelled, Coleman then said he would leave as long as the City issued a written notice of removal. The Clerk agreed and Coleman left.

Let me preamble by clarifying that I am not a lawyer and my understanding of the legal context is strictly that of a layperson and should in no way be regarded as legal advice.

It is true that freedom of the press is protected under the Charter, but that particular right is not the only principle of law in operation here. The Charter also protects people's legal rights in their interactions with the justice system, including hearings.

So there is a need to balance the freedom of the press with the right of defendants and appellants to receive a fair trial.

The general argument against cameras in courtrooms is that active broadcasting raises anxiety for all involved, intimidates some participants, incites other participants to grandstand, and unnecessarily invades people's right to privacy.

In contrast, the general argument for cameras in courtrooms is that it there is an overriding public interest in making court cases accessible to people who cannot attend in person.

In Canada, different jurisdictions have different policies with respect to cameras in courts. The Supreme Court actually records and broadcasts most of its hearings on CPAC, the not-for-profit Cable Public Affairs Channel, and archives them on its website.

In Ontario, Section 136 of the Ontario Courts of Justice Act prohibits photographs, audio and video recordings in court hearings without express permission of the judge, allowing only handwritten notes and sketches. Ontario is an outlier in this practice, as most other provinces have more liberal policies on recording and broadcasting court hearings.

This balancing act between freedom of the press and the right to a fair trail applies in Federal and Provincial courts, but it also applies in quasi-judicial tribunals, which are subject to a body of statutory and case-law restrictions on journalism. According to the Canadian Judicial Council guide, The Canadian Justice System and the Media [PDF]:

Tribunals are quasi-judicial bodies that operate like courts, holding hearings and canvassing evidence to resolve disputes over workplace standards, settle claims for compensation, set power rates, and review police actions or human rights violations, to name just a few of their roles.

Tribunals are open to the public (except where public security or privacy overrides the public interest), but the rules for recording and broadcasting at a tribunal are not the same as the rules for recording and broadcasting, say, the Public Works Committee.

As the debate continues in Federal and Provincial courts over where to balance press freedom and fairness continues, a parallel debate is happening over where to draw the line in tribunals.

The case against recording and broadcasting tribunals holds that it is distracting and unnerving for participants and that it can lead to increased formality (out of fear of being recorded saying something damaging) and a resulting loss in expeditiousness.

On the other hand, refusing to allow recording and broadcast might create a perception that there is something to hide and could even undermine the perceived legitimacy of the hearing. In cases where the proceedings are in dispute, a recording and transcript can help to settle the matter.

The Property Standards Committee is a municipal committee, but it also serves as a quasi-judicial tribunal under Provincial statute. In this particular case, the meeting was a hearing for a property owner to appeal a municipal work order on the property.

Last year, the City of Hamilton adopted a broadcast policy for the Property Standards Committee, but it's not very easy to find. You can read it by visiting the Property Standards Committee web page and clicking to expand the section titled, "Policy respecting the Broadcasting and Recording of Hearings".

It states in part:

1. Subject to sections 2 through 8, a hearing before the Property Standards Committee ("Committee") may not be recorded/broadcast unless prior permission has been given by the Committee.

A statement will be read at the start of the meeting by the Committee indicating that this is the case.

Coleman was late to arrive at the March 7 meeting and was not present to hear this statement. When he arrived, he took a photograph of the meeting and tweeted that it was in progress. He also took a photograph of the work order under appeal and tweeted it.

The City Clerk and solicitor took exception to this and demanded that he stop recording and broadcasting the meeting, and the rest is history.

In the aftermath, City solicitor Nicole Auty, responding to a question from Ward 3 Councillor Matthew Green during the March 8, 2017 Council meeting, responded, "The policy itself doesn't contain a specific definition of 'broadcast'. There is court decisions on what that means, but it, again, it's open to interpretation of what that is."

RTH attempted to obtain the City's definition of "recording" and "broadcasting" that was used in the meeting. After two days and several back-and-forth emails with the City, RTH finally received the following rather tautological definition, which does not appear to be published anywhere on the City website:

Recording and broadcasting hearings means audio or visually recording or broadcasting the proceeding, including taking still photographs of the proceeding. Generally, it does not include live communications in the nature of reporting on the proceeding. Only recording or broadcasting that can interfere with the hearing will not be permitted.

According to the definitions in the federal Broadcasting Act:

broadcasting means any transmission of programs, whether or not encrypted, by radio waves or other means of telecommunication for reception by the public by means of broadcasting receiving apparatus, but does not include any such transmission of programs that is made solely for performance or display in a public place;

And:

program means sounds or visual images, or a combination of sounds and visual images, that are intended to inform, enlighten or entertain, but does not include visual images, whether or not combined with sounds, that consist predominantly of alphanumeric text;

Given this definition, it would appear that Coleman tweeting a photograph of the meeting could qualify as a broadcast of the hearing (whereas the photograph of the work order would not).

Given that the Property Standards Committee broadcast policy a) is difficult to find and b) does not actually include a defition of "broadcast", I think it's fair to say this situation could have been handled better.

There is also a longstanding pattern of hostility toward Coleman at City Hall. He and his journalism platform The Public Record have faced steady opposition and obstruction, including harassment and even physical assault from city officials. He has also been maliciously accused of "fake news" for sharing undoctored, in-context video clips from Council and committee meetings.

The ham-fisted way in which he was removed from the Property Standards meeting must be regarded in this context. It would have been entirely legal and proper for him to continue tweeting reports from the meeting. Only the first photograph he took was arguably in violation of the policy - a policy, again, that was only recently adopted, is hard to find, and does not define its central term.

Instead, he was ordered to power down his device entirely and then ordered to leave the meeting when he refused. This just feels arbitrary and needlessly combative. The City's vendetta against Coleman is blatant enough that other journalists are noticing it.

And this is before even confronting the question of whether the City should actually be leaving it up to appellants at a municipal tribunal to be responsible for deciding whether anyone is allowed to record and broadcast the meeting. At a minimum, this puts appellants in a difficult position and could potentially create a negative public perception if they choose not to allow recording and broadcasting.

With respect to Robert Miles, the appellant at this particular hearing, it is important to quote Coleman's response to RTH at some length:

Mr. Miles and I spoke Tuesday morning. He stated to me that he didn't realize that it was me in the meeting as he's used to seeing me with my camera and laptop. He was frustrated that the City stopped him in the middle of making a statement in regards to his position, and he values my work covering City Hall as there are many meetings he cannot attend that he follows my coverage of.

It is unfair to him to be dragged into this ongoing dispute with the City Manager's Office about my making public agendas and meetings available when the City does not. I've found Mr. Miles to be very professional and forthcoming in the past, I've always received courteous professional answers from him and his staff when I ask them questions as a journalist, and I do not wish the public to believe he was trying to hide anything in this meeting in regards to the Gore Buildings.

The fact is that the appellant should never have been put in the position of deciding, on the spur of the moment, the terms under which a journalist in attendance should be allowed to report the meeting.

The city's tribunal broadcast policy should be clear, it should be consistent, it should strike a reasonable balance between competing rights, and it should be applied fairly and consistently.

By JoeyColeman (registered) - website | Posted March 10, 2017 at 12:35:20

To add context, I've only recorded video in one meeting of the Property Standards Committee during the past five years. This hearing was 1 St. James Place and Victor Veri wrote the City asking that cameras be allowed in the meeting. He believes the City is unfairly requiring him to maintain the building.

I filmed because there were many vectors of public interest in the matter. I haven't seen any public interest in filming citizens engaged in property matters. Any public interest story would be the result of finding patterns by covering all meetings. Most of my stories are the result of finding systemic issues at City Hall - which is partially why the City is so resistant to me mere presence (camera or no camera) at City Hall.

I'm covering these meetings to make sure good process is followed. There's an irony that just being there on Monday exposed a completely broken policy.

In regards to Committee of Adjustment, I've only filmed once: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dcUfjdpq...

The City objected, and the CoA denied the objection because the applicant - the Waterfront Trust - is a government body. I haven't filmed CoA since, because I don't see doing so to be in the public interests.

CoA requests that I inform the Chair I plan to record. In theory, the Chair can forbid my recording of the meetings. In practice, I've never sought to record private citizens seeking variances, and the Chair understands the importance to his committee of the public being aware of their decisions.

Comment edited by JoeyColeman on 2017-03-10 12:38:33

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?