I'd lived in Hamilton almost a decade before I discovered Central Park. Subsequently it would come upon me like an old friend with answers to questions I didn't know I'd asked.

By Mark Fenton

Published September 28, 2015

The strings represent the night sounds and silent darkness-interrupted by sounds from the Casino [...] of pianolas having a ragtime war in the apartment house "over the garden wall," a street car and a street band join in the chorus-[...] a cab horse runs away, lands "over the fence and out," the wayfarers shout-again the darkness is heard-an echo over the pond-and we walk home.

— Charles Ives on "Central Park in the Dark"

I wanna go over the Berlin wall

Before they come over the Berlin wall

— Sex Pistols "Holidays in the Sun"

I'd lived in Hamilton almost a decade before I discovered Central Park. Subsequently it would come upon me like an old friend with answers to questions I didn't know I'd asked. Here are some observations about its ongoing relationship with me.

By no mental gerrymandering can I make it be "central" to Hamilton or any other obvious geographical outline.

I can never find it when I go looking for it, and I never fail to run into it when I'm not looking for it.

It's sunken and enclosed

by the building around it. The kind of walls that feel impossible to get over.

I would upset fellow Hamiltonians and just plain be exaggerating if I said it has qualities of a prison yard but the sense that 'you can't get there from here' feels almost political. On a more affirmative note it could be described as an oasis amidst the imposing industrial structures from an age when multi-storied brick buildings housed hard labour. And yet,

a palpable negative space.

A friend I was talking to about the project missed the mention of Hamilton and assumed I was photographing Central Park, New York. Kind of throwing down the gauntlet when you name your park after the most famous public space in North America, don't you think?

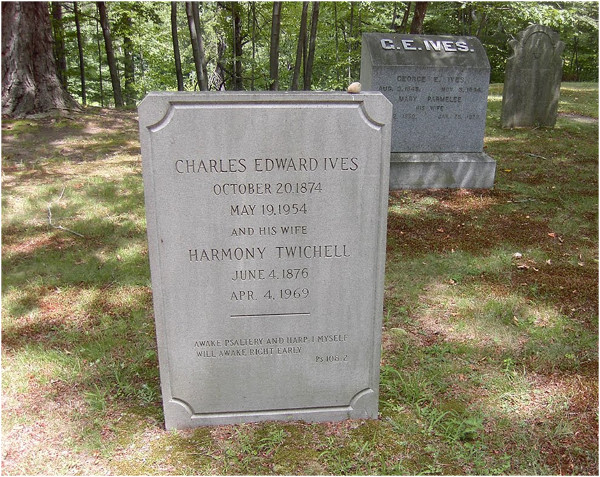

What had inspired me to go there late in the day on a day in late summer was that I'd been listening obsessively to "Central Park in the Dark," a 1906 orchestral composition by Charles Ives.

'So,' I thought idly, wishing the air conditioning in a century-old double-brick house was a bit more effective than it ever can be, 'why not visit the nearest central park, in the dark, while listening to an orchestral piece for which it is semi-eponymous.' It doesn't take much to urge me outside with my camera, and it would be cooler in the park than in the house.

I downloaded the composition onto my iPod and out I went. Alas, it was too dark to get there safely via SoBi bike. So I went into the night on foot.

And why not? People do it all the time. They don't Google hours and admission costs. They just show up. Parks are one of the few public destinations that are both free and open 24/7. Perhaps this knowledge will comfort me when I awake from that recurring anxiety dream where I've lost everything and have nowhere to go.

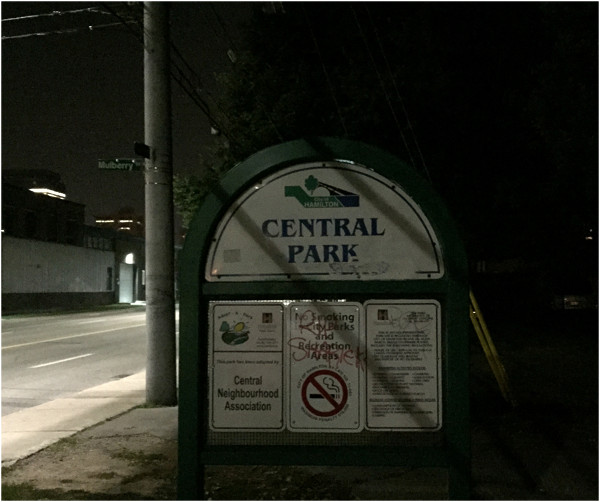

Note how perfectly the shadowfall on the entry sign

makes it a coat of arms

with a bend dexter strap.

Its angle parallels the bend of the smoking prohibition. Impressing on me that the 'no smoking' icon, right-side up or upside-down, is always bend dexter

(where I personally think bend sinister might convey a cautionary subliminal menace).

"Central Park in the Dark" begins with strings edging into the night at a glacial tempo. It's eerie. You can be pretty sure this piece wasn't commissioned by NYC tourism.

This is the soundtrack I've chosen rather that the useful sonic information granted to open ears. In other words I am traversing this space under headphones without any knowledge of what or whom is around me. If ne'er-do-wells wish me harm I will not hear their approach until it is too late.

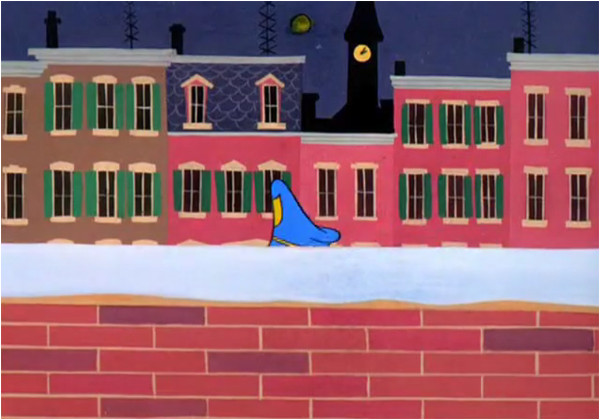

Here's an image taken from a fan's version of "Central Park in the Dark" on Youtube. It's striking how little it matters what park you are in on a summer night. The images are roughly the same.

A Fan's Central Park, New York

My Central Park, Hamilton

Perhaps, you'll say, these similarities are to be expected of such a generic subject. And indeed, generic subjects are my nemesis. For as always, when I get home and upload the photos to my computer I am charged with an excitement I never outgrow, followed by a letdown I never see coming, i.e. "What exactly was Walker Evans doing with his camera that escapes me?" On this trip, squeezing something out of nothing was harder than usual and I was jittery as I rode my iPhone camera into the field, understanding well Lawrence Ferlinghetti's description of the poet who,

"like an acrobat

climbs on rhyme

to a high wire of his own making"

The one thing I'd gained from my orchestrated nocturnal visit was a spare stage set in the dead centre of the park, crowned by a single orb.

The light that died perfectly at the limits of the mound made it a theatre where children's toys, lost in daylight hours, might come to life and enact dramas too lonely for an audience.

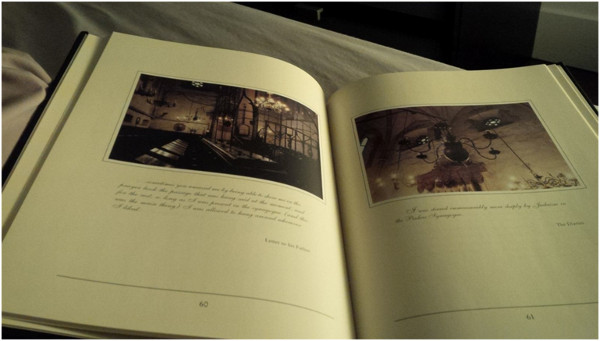

After uploading the photos I checked my e-mail. A friend had just sent me a photograph of an opened book on Kafka she'd picked up in Prague.

A Friend's Photo of *Kafka and Prague*, Karol Kállay, Slovart Publishing Ltd. 2005

Below each image is a quote, describing Kafka's childhood recollections of the synagogue. It's a stark photograph both for the austerity of the book design and the simplicity of the drapery on which it has been placed, like a museum display after hours when even the guards have gone home.

It's a photograph of photographs, reminding us that at a certain age we are so distant from childhood we have only a memory of memories.

The park at night is empty and strange. Parks are above all for children, but children are gone, along with their laughter and games and toys. They take their memories with them.

I didn't expect a 'story' in the journalistic sense. But I got nothing at all. Believing that if you nag away at a plot of land long enough with a camera something imageworthy and/or textworthy will present itself, I returned to Central Park during the day. This time I did grab a SoBi bike, from a dock with a delightful Hamilton backdrop

from a completely unrelated Hamilton park that in retrospect was just full of stories. (What is wrong with me?)

Back at the park that I'd stubbornly committed to documenting I felt like the frightened child whose parent convinces her things at night simply look different, and more threatening than in daylight. e.g. The light standard which at night glowed like a preternatural force that might consume me proved in daylight to have its head completely buried in foliage.

The head of the lamp is only visible at night. Like a phenomenon of physics that we know to exist solely because its remarkable behavior does.

"One Froggy Evening" is a seven-minute Looney Toons opus directed by Charles M. (Chuck) Jones and first shown in 1955. If I can do this summary from memory that's because as a five-year-old living in Regina before cable I saw "One Froggy Evening" so many times that I will likely picture a mental frame from it at the moment of my death.

A multistoried brick building is being brought down by a wrecking ball. Amidst the destruction a blue (literally) collared and (alarmingly) unhelmeted demolition worker (hereinafter referred to as DW) is standing before a concrete vessel, not so much demolishing it as deconstructing it inquisitively with a crowbar.

He finds within it a smaller vessel, the size of a shoebox, in which resides a frog (hereinafter Frog) and some opaquely written papers of the building's provenance, dated 1892. That Frog has survived these decades unfed in this sterile double container should have the tipped DW off as to something being decidedly 'up,' but we're guessing he's not the keenest blade on the rack.

Frog, knowing a sucker when he sees one, and motivated either by misdirected vengeance for decades of imprisonment, or for the love of a high concept prank, produces a top hat and a cane and begins singing "Hello, My Baby!" even then a song of yesteryear.

It's all good. The song is happy, the singing unambiguous and fully engaged, and Frog moves diagonally across the rectangle like a bend dexter.

DW sees dollar signs. Who wouldn't pay to see a singing/dancing frog?

Here's the catch. Frog only performs for DW. When DW presents Frog to a theatrical agent, Frog just lies there and croaks. DW is shown the door. (More dramatically than 'shown'. This is Looney Toons animation.)

Whenever DW is alone with Frog, Frog sings lyrically. And the number is always conspicuously pre-20th century (Frog has clearly been doing this for a while.) Whenever other people are present Frog is just a frog. DW thinks he can get past this problem by going D.I.Y. His own money, his own production, his own promotion. Once again, Frog performs beautifully for DW in rehearsal and then goes back to being a frog as soon as an audience is seated and the curtain goes up.

The cartoon ends with the financial and psychic ruin of DW who finally dumps Frog in a condemned building much like the one in which he found the malign croaker. Flash forward a hundred years. A new DW (now wearing a clear spherical head protector and some kind of laser gun to demo heavy objects-the future has changed a lot since the 50s) comes across the box.

Frog is still alive after yet another century without a bite to eat. Frog beings to sing and dance to "Hello, My Baby!" Twenty-first century DW gets dollar signs in his eyes and tiptoes away with his moneymaker. You get the idea.

I wanted a break from Central Park so I went the Tim Horton's just south of it. There I sat watching "One Froggy Evening" for the millionth time on my iPhone. Sipping one in a series of green iced-teas I looked up from the cartoon to observe the solitary men and women crossing the Bay and Canon intersection. Men and women with dreams and plans just as urgent as DW's. How many will realize them?

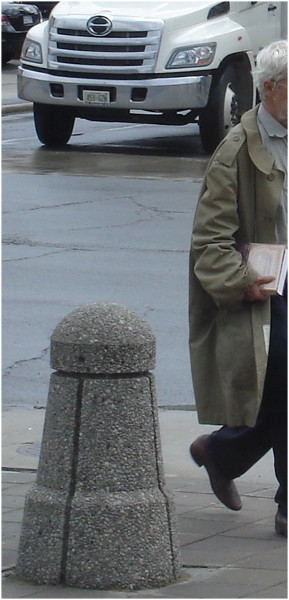

I notice a man particularly intent on whatever muse drives him across streets of Hamilton. My camera snatches him from eternity as he passes a concrete pillar in front of the Tim's. The pillar is there to prevent vehicles driving up on the patio stones, but taken out of its context it points heavenward, and is redolent of fertility, incarnation, the outer limits of aspiration.

I long to know whether that book under his arm teaches how one might harness the entertainment potential of a anthropomorphic amphibian, or if it directs some similarly noble yet elusive ambition.

But he's moved beyond the edge of the camera's rectangle

and taken his dream with him.

How do I make the frog who sings and dances for me sing and dance for my readers? For while every moment of my Hamilton journey with a camera is an adventure of looking and framing, as though I myself am creating little squares of a world where no one has ever been. It is very difficult to communicate this to readers.

There is a harrowing scene near the end of "One Froggy Evening" (surely few entertainments intended for children are so uncompromising in their portrayal of failure) in which DW has spent all his money and is homeless in a public park (Central Park?) as Frog, with La Scala-worthy brio, sings Figaro's aria from Il Barbiere di Seviglia. A policeman hears this over the park wall.

He goes into the park. Questions DW on where the singing is coming from (Singing in the park? An affront to mid-20th century urban peace? Lord help this officer if he serves another quarter century and has to deal with ghetto blasters.) DW motions to Frog, who has once again reverted to the very essence of frogness.

DW is carted off to the psychiatric hospital (yes, it was way easier to have someone committed in the '50s) and we see DW seated in catatonic anger as frog croons "Please Don't Talk About Me When I'm Gone" using one of the psychiatric prison bars as a stage prop.

Uneasily I identify with the man desperate for others to see the magic that he sees, hear the music that he hears. Leaving the Tim Horton's I stop in the parking-lot to ponder a perimeter whose bricks and prisonlike backdrop echo DW's incarceration so perfectly that I shoot it

and shoot it

and shoot it

like a man unloading ammunition into an enemy he wishes he could kill and kill and kill until he feels avenged.

Eventually I become aware of staff watching me so I go back inside and order another green iced-tea, believing I'll avoid interrogation if I continue to spend money there.

Was I trying to go "over the garden wall" as Ives says in the epigraph at the head of the essay? Or was I trying to go over the Berlin Wall as Johnny Rotten says in the epigraph that follows it?

A few years ago I shot some photos in Central Park New York

which might well illustrate Ives's detail of an "echo over the pond." (Clearly the splash pad at Central Park Hamilton wasn't going to convey sound over water.)

But at the time I'd forgotten all about my New York photos and so I Googled 'Parks with Ponds' and stumbled onto this image of the Stadtpark in Steglitz, Berlin. In seconds I was embedded in a historic European drama I can't possibly keep out of the essay.

I'm taken back to the Berlin of the cold war era. Specifically, the Berlin Wall that had been its metaphor for longer than I'd been alive. Escape from communism by going over the wall, or conversely, the fear of communism coming over the wall for us. It's a menace I felt intensely the first time I heard Johnny Rotten's declamation, the voice frightening, manic and infantile, like an ADHD boy with a speech impediment. It still isn't clear to me which side of the wall he thinks is worse.

In 1923-having only a year to live-Franz Kafka left Prague for Berlin, and landed in the nightmare of Germany's postwar hyperinflation. The vagrancy of Chuck Jones's very American DW in the last stages of financial despair would hardly have been noticed here. A man claiming his frog could sing would be the least of the Schutzpolizei's concerns.

Kafka was living with a young woman named Dora Diamant. One day, while in the Stadtpark, Kafka and Dora came across a little girl crying because she had lost her doll. Franz told her that her doll was not gone, that the doll was simply growing up and wanted to do things outside the household. And that in fact he, Franz, was in possession of a letter from her doll.

The little girl was doubtful (and probably a bit weirded out. I'm guessing that even in 1923 you were taught to be wary of strange men in parks over-interested in your toys) but Franz said he would bring the letter the next day.

Dora tells us that Kafka went home and wrote a letter with the care he took in all his writing. And the next day Franz and Dora again met the little girl in the Stadtpark and he gave it to her.

Over the following weeks he continued to invent letters from the doll to the little girl, thus creating an epistolary children's novel. The loss of the doll ceased to concern the girl. She just hungered for the next letter, knowing her doll still existed because her doll's remarkable behavior did.

Finally Franz told the little girl that her doll was engaged and making wedding preparations. So she could hardly continue corresponding with a childhood friend, could she? (Insert feminist observation that friendships outside her husband's social sphere ended on a Weimar bride's wedding night and that observation would be both accurate and lamentable.) Kafka-as-doll communicated that all things pass away. As one door closes another opens. Things will get better. (Though they didn't for Kafka, or for a whole lot of Berliners.)

The little girl has never been identified. The letters have never been found. And I doubt anyone's gone looking for the doll. We have only Dora Diamant's testimony that the episode ever happened. You decide if the frog really sings, or if it's the product of a deconstruction worker just trying to get noticed.

ca. 1924, Franz Kafka Museum, Prague.

I've returned from my daytime shots of the park and I'm indoors typing and listening to "Central Park in the Dark." It is not dark. It is mid-afternoon, Labour Day Monday, September 7th. For many of us it's the last relaxed day before the business year starts up again.

I never tire of the piece. It's quintessential Ives. The dissonant ambient strings set a haunting backdrop, equal parts nurturing and menacing, amorphous and ubiquitous, in keeping with all urban geographies at night. The second instrumental section consists of two piano players who sound increasingly inebriated and inept as the piece progresses.

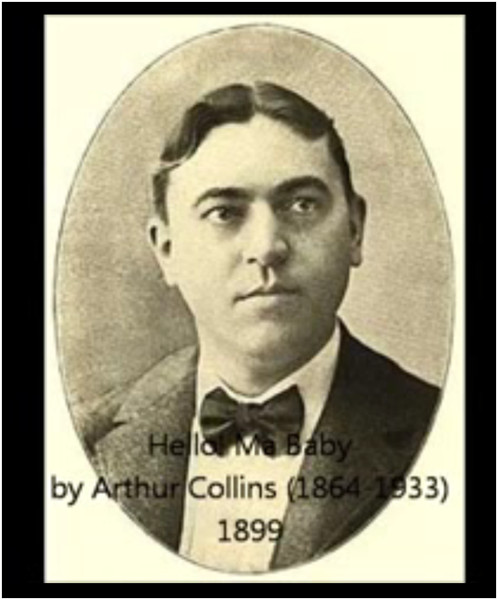

Ives specified that one instrument should be a concert grand and the other should be an upright player piano. (Think of a Stradivari virtuoso jamming with a gypsy street fiddler. It's not just the clash of timbres. It's the clash of cultures.) They collaborate on an inept piano version of "Hello My Baby!" then a recent hit as sung by Arthur Collins

on an Edison 5470 phonograph cylinder, transferred through heaven knows how many audio technologies on the way to Youtube, from which video I grabbed the photo above.

The third instrumental section, brass and winds, announces itself as a sober, polished-to-godliness Salvation Army band playing for the lost denizens of the big city. Half way through though the players are seduced by the honky tonk music they've been resisting so stolidly.

The tipping point occurs when the clarinetist figures out what the piano duo is trying to play, and answers back with a similar but shriller "Hello, my Baby!" not so much in musical collaboration, as in mockery. The way cruel boys would imitate the whine of the ADHD boy with a speech impediment. Or the way cruel girls would imitate sobs of the girl whose doll they've stolen.

It's a rare moment of contact. Through most of piece none the three sections appears to be listening to the other two. Familiar melodies are everywhere, but they're all horribly damaged. The cultural bric-a-brac we absorb without knowing it, and which roots us happily in the quotidian, has become distorted and sinister.

It would be fitting if Central Park in the Dark premiered in Central Park NYC on a summer night. But it didn't. The first noteworthy performance was by the Julliard School in 1946, decades after Ives had given up composing in response to a public that had as much interest in his music as they would in a man who insisted his common and very limp frog could metamorphose into a song and dance man.

For the sake of historical integrity Ives didn't want the piece billed as a 'first performance.' He dimly recalled it being performed between the acts in a very off-Broadway theatre. He couldn't remember the name of the theatre. He couldn't remember the year. Had to go D.I.Y. His own money, his own production, his own promotion.

The musicians had a hard time with it. One of the piano players got mad half way through, gave up, and kicked the bass drum and walked out. I'd really like to know if it was the classical pianist annoyed by its flagrant disregard for conventional harmony and rhythm, or the guy on the player piano impatient with its aspirations to highbrow modernism. But that answer is lost to history, and perhaps even to Ives's memory when he recounted the episode.

The anecdote is stirring. It's been a long time since musicians have been driven to musical violence by the shock of the new. It's also sad. The composer doesn't remember where or when his masterpiece was first performed and doesn't much care to. Like DW's frog discarded gleefully in a condemned building it's a bleak hiatus. The dream interred pending resurrection.

By Fred Street (anonymous) | Posted September 29, 2015 at 09:27:19

The City will undoubtedly promote it more once it's been properly remediated.

thespec.com/news-story/2215232-toxic-past-and-present

thespec.com/news-story/4401450-central-park-toxic-soup-needs-study-report-says

thespec.com/news-story/5347139-city-ready-to-spend-3-7m-sealing-off-a-toxic-soup

By mpclarke (anonymous) | Posted September 29, 2015 at 12:32:29

Thanks for this piece Mark.

I discovered Central Park on a walk about a few weeks ago. There is a small concrete splash pad which overlooks some open parkland 9(you posted a picture of it in your essay). The parkland initially falls away from the splash pad and then gently rises to the perimeter of the park. There are some smallish trees planted about.

The whole space is a perfect little amphitheatre and I had this vision of a sunny summer Saturday afternoon, a stage set up on the splash pad, some balloons, kids and their families on blankets, dogs and burgers on the barbeque, and some music - like a micro Woodstock.

Let's do it. . .

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?