he Church of Our Lady is magnificently located atop 'Catholic Hill' that dominates the city of Guelph to this day.

By Malcolm Thurlby

Published September 25, 2015

On December 8, 2014, Pope Francis elevated the Church of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, Guelph, to the status of Basilica of Our Lady Immaculate. The Very Reverend Monsignor Murray J. Kroetsch, Director of the Liturgy Office of the Diocese of Hamilton since 1981, said, "It's a great honour for the church and for the community of Guelph because that church is such a beloved church".

A great honour, indeed, and one that is nobly reflected in the architecture of the church, which has recently undergone extensive restoration at a cost of over $12 million.

Fig. 1. Guelph, Basilica of Our Lady Immaculate, exterior from liturgical NE (magnetic SW).

The Church of Our Lady is magnificently located atop 'Catholic Hill' that dominates the city to this day (fig 1). To Irish eyes it can't fail to recall the cathedral atop the iconic Rock of Cashel (Co. Tipperary).

The present church replaced the humble wooden St Bartholomew's of 1827. Plans for an even grander church were underway in 1863 and a foundation stone was laid. But the project proved to be too ambitious.

The sod for the Church of Our Lady was turned on July 10, 1876. On November 1st, 1876, The Guelph Mercury and Advertiser reported, "It is now nearly three months since the excavation for the foundation was commenced and already the entire basement at the back of the church which rises 14 feet in the clear has been completed, and the public by examining the walls can even now have something of an idea of what architectural beauty the edifice will be when completed."

The foundation stone was laid on July 5, 1877, by Monsignor Conroy, Bishop of Ardagh and Clonmacnois and Apostolic Delegate to the Dominion of Canada. On November 14, 1877, it was announced that "[t]his building which is now rearing its head above all other edifices in town, will be an architectural ornament to and a standing monument of the liberality and enterprise of the Roman Catholic citizens."

The report added: "This year some $30,000 has been expended in addition (to the $10,000 last year) and before it is completed $60,000 more will be required." It is also observed that: "[t]he work done up to the present time includes the walls encircling the nave and chancel and the small chapels at the rear. All this is expected to be roofed before winter sets in."

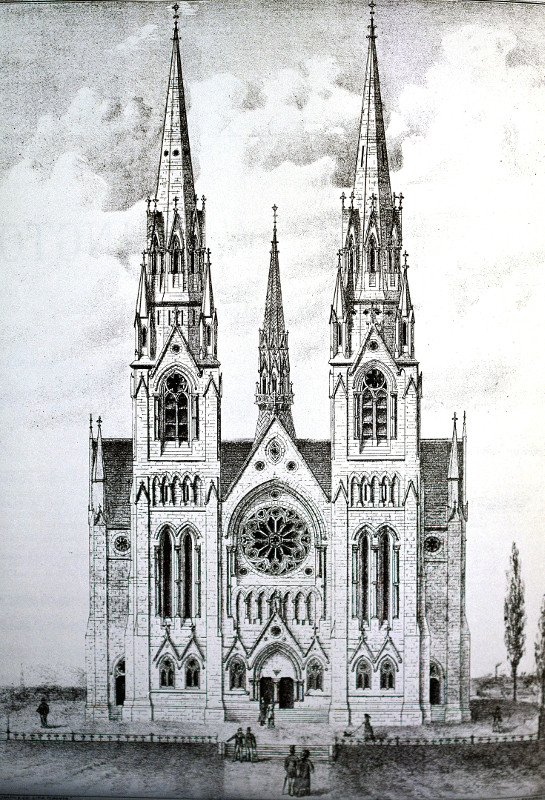

After a break in construction, work on the nave was continued in 1885, and was completed, with the exception of the superstructures of the towers, for the consecration of the church on October 10, 1888. The towers were erected in 1926 albeit without the spires intended in the original design (figs 2 and 3).

Fig. 2. Guelph, Basilica of Our Lady Immaculate, W (E) façade.

Fig. 3. Guelph, Basilica of Our Lady Immaculate, façade as planned (Historical Atlas of Waterloo and Wellington Counties, 1881).

The architect of the Church of Our Lady was Joseph Connolly (1840-1904) who had emigrated from Ireland to Toronto in 1873. There he established an architectural practice with the architect/surveyor/engineer, Silas James. The partnership lasted until 1877, after which Connolly practised alone until 1896.

Trained in the Dublin office of James Joseph McCarthy (1817-82), Connolly soon established himself as the preferred architect for Roman Catholic Church commissions in Ontario, especially for Irish patrons. He revolutionized Catholic Church architecture in Ontario through the application of the True Principles of Augustus Welby Pugin (1812-52) published in 1841.

Pugin equated the Pointed, or Gothic, style with Christian architecture as opposed to the Classical style of the Greco-Roman tradition, which had pagan associations. To revive Gothic architecture, Pugin advocated the close study of medieval churches, the replication of specific motifs and the very methods of construction.

The vast majority of church architects of the 1840s followed Pugin's advice with enthusiasm, not least James Joseph McCarthy, who became known as the 'Irish Pugin'.

Perhaps not surprisingly, when architects felt confident in designing churches in the Medieval Gothic mode, they began to consider what contemporaries called 'development', in other words the adaptation of medieval designs to the wants of the 19th century. One outcome of this is the so-called High Victorian Gothic which, rather than focusing on regional medieval sources, would incorporate elements from across Europe.

The result is greater monumentality, especially for churches in urban locations known as 'Town Churches', and polychromed and/or richly textured walls. It is through the High Victorian lens of James Joseph McCarthy, and the Irish churches of the contemporary firm of Edward Welby Pugin (1834-75) and George Ashlin (1837-1921), that Connolly's Guelph Basilica is to be seen.

Since 1908 the Church of Our Lady has been compared with Cologne Cathedral, although Connolly's own description of his design says that it is based on 'early 14th-century French sources'. What the Guelph Catholics got was the equivalent of a Franco-Irish Cathedral, even though the church was not the seat of the Bishop.

It was close enough to Cologne Cathedral in appearance - albeit significantly smaller - to make the community very proud. It gave Bishop Crinnon (1818-82) a cathedral-like building in his Hamilton diocese; his Cathedral of St Mary in Hamilton of the early 1860s was inspired by the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome, the design of which is also reflected in St Augustine's, Dundas.

Connolly's apse-ambulatory plan with radiating chapels remains unique in Canada and is not even presaged by a 19th-century example in Ireland. And, while St Patrick's Cathedral in New York City (1858-79) has an apse and ambulatory, the east end finishes in a square termination.

The closest to Connolly's Church of Our Lady at Guelph - although not necessarily known to him - is St Patrick's Cathedral, Melbourne, Australia, built for the Irish Catholic community to William Wilkinson Wardell's 1858 design.

19th-century apse-ambulatory plans with radiating chapels are used for Sainte-Clothilde, Paris, by Franz-Christian Gau (1846), Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Belleville, Paris, by Lassus (1854-59); 'Cathedral' by Viollet-le-Duc; and the Votivkirche, Vienna, by Heinrich von Ferstel (1856-79).

All of these churches have twin towers and spires for the west front, as at St Patrick's Cathedral New York City, a feature which was introduced on the façade of Armagh Cathedral by J.J. McCarthy when he took over as architect there from Thomas J. Duff (d. 1848) in 1854. Except for Armagh and Melbourne, these churches have rose windows in the façade as at Guelph.

And, if all that was not enough, the Catholics got a bigger and better church than the one recently built for the Anglicans of Guelph by Henry Langley. Connolly's interpretation of a French Rayonnant sources includes a full basement, a feature adapted from Baptist, Methodist and Presbyterian churches in Ontario. He omits flying buttresses because of the absence of stone high vaults, and delicate traceried gables of the Rayonnant are more solidly rendered by Connolly.

The three-storey elevation of the Church of Our Lady, comprising a pointed main arcade, triforium and clerestorey is unusual in the 19th century, even for cathedrals, as witnessed by McCarthy's Monaghan Cathedral (1861), and Connolly's own St Peter's Cathedral, London (1880) (figs 4 - 6).

Fig. 4. Guelph, Basilica of Our Lady Immaculate, interior to E (W)

Fig. 5. Monaghan Cathedral, interior to E, J.J. McCarthy (1861).

Fig. 6. London, ON, St Peter's Basilica, interior to E (N).

A contemporary description of the Church of Our Lady records: "Great dignity is added to the interior by the grand triforium, which extends all round the church, between the great arcades and the clerestory windows. It is a novelty in this country, being, we believe, the only one of its kind in the Dominion, and will consequently be an additional characteristic of this great building which, when finished, will not only be a landmark of our future city, but also one of which our whole Dominion may feel proud." (The Irish Canadian, July 18, 1877, 2, col. 4)

Once again, at the dedication of the church, it is recorded that above the main arcades, "we see a feature of Church architecture rare on this continent, the triforium, a passage gallery or tribune leading over the aisles, and opening above through traceried arches, into the church, and formerly used by the friars in the chanting of the sacred offices." (The Irish Canadian, October 18, 1888, 2, col. 3)

While the association of friars chanting takes on a romantic note, associations with the "great mediaeval Cathedrals" also made in the sermon are very much to the point. Both the early Gothic Christ Church and St Patrick's cathedrals in Dublin boast three-storey elevations, and 19th century Irish precedent for a three-storey scheme is found in St Patrick's Cathedral, Armagh (1840-1904), and Pugin and Ashlin's St Colman's Cathedral, Cobh (1868-1915).

While lacking three storeys and an apse-ambulatory plan, McCarthy's Monaghan Cathedral provides the source for much in Connolly's design at Guelph. The bar-tracery clerestorey windows of the apse, proportions of the pointed main arcades, details of the ultimately early Gothic French acanthus capitals, larger arches leading to the transepts with correspondingly larger piers, and the high wooden vaults in the sanctuary are common to both churches (figs 4, 5 and 7).

Fig. 7. Guelph, Basilica of Our Lady Immaculate, capital.

Fig. 8. Kilcullen (Co. Kildare, St Brigid, interior to E, J.J. McCarthy (1869).

Fig. 9. Monaghan Cathedral, W front, J.J. McCarthy (1861).

The shafts of Connolly's main arcade columns are of polished granite rather than plain limestone at Monaghan, a feature inherited from other McCarthy churches such as Sacred Heart and St Brigid, Kilkullen (Co. Kildare) which was built in 1869 when Connolly was chief assistant in McCarthy's office (figs 4 and 8).

The hammer-dressed masonry with smoothly finished dressings is common to both the Church of Our Lady and Monaghan Cathedral. Connolly's west (east) front also took many details from Monaghan (figs 2, 3 and 9).

For the main entrance the doorway with tympanum and trumeau beneath a moulded pointed arch within a sharply pointed gable flanked by single gabled arches with figure niches at Monaghan transformed to windows at Guelph. The rose window with pointed enclosing arch follows Monaghan even to the point of plate-tracery roundels in the lower corners.

The blind arcade between the doorway and the rose window at Guelph is absent on the Monaghan west front but is taken from the south transept façade of McCarthy's cathedral (figs 2, 3 and 10). Here we also find the jumping-off point for the design of Connolly's intended spires, the open corner turrets of which recall French 12th-century sources such as Laon Cathedral.

While the Guelph spires were not realized, his spires were completed at St Mary's, Bathurst Street, Toronto (1885), and St Michael the Archangel, Belleville (1886, rebuilt 1904).

The basement of the Church of Our Lady may not be as architecturally exciting as the superstructure but it is historically significant for its use of cast-iron columns, a material that grew in popularity in the second half of the nineteenth century (Figs 11 and 12).

Cast-iron columns offered far greater support than stone or wooden columns of the same size and, consequently, facilitated the creation of a more open space. The casting process also allowed for the acanthus foliage capitals at a fraction of the cost of sculptured stone or wooden equivalents (Fig. 12).

Fig. 10. Monaghan Cathedral, S transept façade, J. J. McCarthy (1861).

Fig. 11. Guelph, Basilica of Our Lady Immaculate, nave basement.

Fig. 12. Guelph, Basilica of Our Lady Immaculate, nave basement, detail of cast-iron capital.

It is worth noting that elements used by Connolly at Guelph conform happily to near-contemporary Catholic church design in Ireland. For instance, William Hague's St Patrick's, Trim (1891-92) shares the use of polished granite columns for the arcades and the larger pointed arches to the north and south transepts. Hague's wooden rib vault in the choir is similar to Connolly's at Guelph, while Hague's hammerbeam roof in the nave is allied to Connolly's at Macton and elsewhere.

One aspect associated with the status of a Basilica is that it will be a place of pilgrimage. With that in mind I urge those of you in Hamilton to make the short journey up Highway #6 to the Basilica of Our Lady Immaculate in Guelph.

By Bryce (anonymous) | Posted September 25, 2015 at 09:23:57

Great history/architecture lesson - thanks for posting!

By CharlesBall (registered) | Posted September 25, 2015 at 10:07:54

Perhaps you can confirm. As I understand it, the original plans were to build a church that would have rivaled St. Peter's in Rome. It was funded by Maximilian of Mexico but was scuttled by the Mexican "revolution" and his "assassination."

Also, Connolly was the architect for St. Patrick's right here in Hamilton.

Comment edited by CharlesBall on 2015-09-25 10:11:25

By Missy2013 (registered) - website | Posted September 25, 2015 at 11:11:34

Wow. Impressive visuals. Thanks for posting.

By KevinLove (registered) | Posted September 28, 2015 at 04:03:33

I am somewhat curious as to the originally planned and executed landscape architecture.

It appears that the present landscaping is a thoroughly squalid automobile storage area. Presumably something a little less ugly and demeaning was originally present.

Comment edited by KevinLove on 2015-09-28 04:04:18

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?