At a certain age there is simply too much information, too many distinctions to be made, too many identities to be confirmed.

By Mark Fenton

Published June 10, 2015

[E]ven a pamphleteer or writer of textbooks will have pet words and phrases which appeal to him for non-utilitarian reasons; or he may feel strongly about typography, width of margins, etc. Above the level of a

railway guide, no book is quite free from aesthetic considerations. —George Orwell

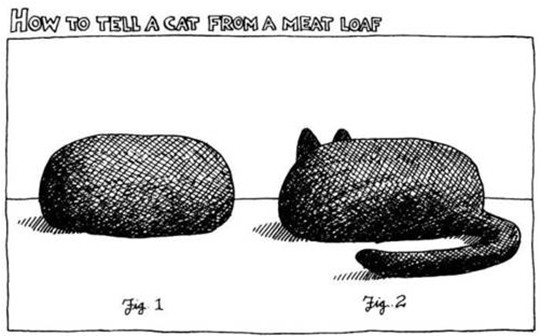

Often when I begin a day and am confronted with a problem I consult the books of my pre-internet childhood. I have moved 12 times since the nurturing and happy home of my youth, so it's not surprising that only a small selection of my childhood books have been kept. One such is B. Kliban's CAT, a visual instruction manual on the felis domesticus.

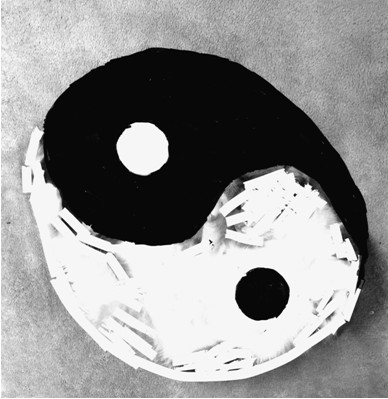

This was just the diagram I needed in order to tackle a problem I had discovered upon waking this morning:

Identification of a soft elliptical object from which a single acute angle protruded. Kliban's book is in black and white, and so having no clue as to the colour of his cat and loaf, I reduced my image to the hues and shades of the diagram.

But I remained puzzled. For the object is in the grey area, metaphorically and now literally. It has more definition than a meatloaf and less definition that a cat.

Should I reheat it and see if it's tasty? Or should I leave it and see if the mouse population diminishes?

I struggled with these complexities for some minutes and finally abandoned them. At a certain age there is simply too much information, too many distinctions to be made, too many identities to be confirmed.

I let the problem sleep and left the house.

For several days I had been taking the bus to and from work. My elder daughter needed the car for her job at a more distant location. When that job ended I needed to take the car in for repairs which proved expensive. (Just thinking about the expense is making me grumpy and is probably affecting the tone of my writing.)

You will be joining me for the ride from work, rather than the ride to work. Not for any important conceptual reason, but just because it wasn't until midday on the last day of my HSR commute that it occurred to me an HSR bus might be a good vessel from which to shoot a photo essay. (Duh.)

You can tell it's been a while since I used the HSR, because it was the first time I'd seen this sign

It thrilled me to imagine that the bus was transpondered and that when I called the number a GPS would calculate the arrival time of the specific impeding bus and convey it to the recorded message that spoke to me. However, I soon discovered that the information was consistently identical to that on the printed schedule.

A few days before, the driver (hereinafter referred to as the 'Railway Guide' [title caps]) stepping off the bus during a still point in the route's circuit, noticed me staring at the sign while making a phone call, thus identifying myself as a bus passenger tyro. He handed me what Orwell, in the epigram heading this piece, refers to as a railway guide,

and in homage to Orwell I will continue to refer to this document as a 'railway guide,' distinguishing it from the sentient, reasoning homo sapiens of the same name solely by being written without caps, a decision which - I dare to hope - paves a highway to clarity, but which - I must also fear - gravels a backroad to confusion.

If I seem overly committed to names containing the word 'rail', that's because I find it magnificently metaphorical that Hamilton Street Railway has retained this title despite an absence of rail transport since 1951.

(I'm similarly struck by how everyone in our office refers to 'shipping' packages that move by bicycle, truck, airplane, but never by boat. Do things become more meaningful when we call them something they aren't?)

Orwell died in 1950, so had he boarded the HSR at any time in his sadly abbreviated life, it would have been exactly what the name said it was. The Orwell biographies make no mention of him visiting Hamilton, let alone taking the streetcar, but now the possibility has entered my imagination, thoughts of historic Hamilton will always accommodate a man of military bearing, with clipped moustache, seated on an HSR train, diverted momentarily from his morning Spectator, to gaze quizzically through the coal darkened window into concerns reaching far beyond King Street.

So. I compared the paper schedule with the recorded information enough times to constitute a meaningful sample group. This confirmed that the recorded voice was giving me in an oral form the exact information that the paper copy gave in a written form. Neither of which data sets adjusted itself to the earliness or lateness of the bus. (Not that I expected the piece of paper to. I may be a luddite, but I'm not DSM delusional.)

Having memorized the data of each, I hoped that the train would arrive at the exact minute of the arrival time in my memory, but this was seldom the case. And while ruminating on the problem I recalled Proposition 265 from Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations.

... I don't know if I have remembered the time of departure of a train right and to check it I call to mind how a page of the timetable looked. [...] If the mental image of the timetable could not itself be tested for correctness, how could it confirm the correctness of the first memory? (As if someone were to buy several copies of the morning paper to assure himself that what it said was true.)

When my younger daughter was in Grade One she brought home a photo of her class. As is the case with such photos, the individual faces were quite small, and I misidentified a fellow student with similar hair length and colouring for my daughter. My daughter corrected me. Then she led me to the mantelpiece where she found a larger and more defined portrait of herself and, in the laconic manner of a Zen sensei, pointed to it and uttered the single word 'see,' so that in future I could use it to verify whether or not a face in any photo was hers.

Enough of that. Here's where my journey home begins. And it is very clear we are at an airport. That is the visual information at ground level.

But airplanes move into the sky. As do clouds, which were interesting today. So I tipped the camera 20 degrees back to eliminate the ground. We use the information between the immediate foreground and the horizon for navigation. Move above the horizon and we're lost. I had just pulled the horizon away as a prankster might pull the carpet from under an unsuspecting victim.

The light standards, benign in the first photo, are now terrifying. They have organized and begun moving together like predators in an H. G. Wells novel.

We know not whence they come. We only know they mean us ill. Our best scientists tell us that they can be taken down by a projectile hurled at the place where those eyelike rectangles fuse atop the slender spinal column that drives an instinct as monomaniacal as it is malevolent.

Imagine if Vermeer, when nailing down the composition of View of Delft,

impulsively inclined his camera obscura backward 20 degrees. So that instead of a quaint, not quite bustling city scene, he gave us this instead.

Imagine how geographically disorienting viewers would have found it. How threatening those pokey towers would be. Forever after Dutch museum-goers would stoop to avert their eyes from the tops of buildings, their subsequent spinal curvatures portrayed cruelly by foreign cartoonists as a laughable ethnic stereotype.

CONCLUSION: The tops of pointy things are creepy when disembodied.

Light standards and European turrets incline my thoughts to the tops of things, to the assembled forces of dishes and antennae on the roofs of high-rises

that stand motionless and expectant like elegant birds perched one-legged on shorelines

to snatch signals like insects that they digest and convey down to screens that reassemble the information into images. In order that residents can feed on the movements of a world they need never leave their apartments to experience.

We have come a long way from the days of celluloid, but the consideration of the contemporary machines naturally transports one to the historical journey from which the technology has grown.

The fact that I can ride a public post-rail motor vehicle and record the trip with the essentially foolproof action of an iPhone camera makes me recall a master of photographic images: Yasujiro Ozu, who avoided camera movement, yet consistently shot from inside trains, recognizing that they provided an accidental tracking shot onto the modern world.

Nearly all of his films contain long shots from within a train as a character rides from Shinjuko station to downtown Tokyo.

It is less what one sees out of the window than the FACT of seeing, freed from the responsibilities of driving, that so appeals to me on this bus trip. During this reverie of motion and its documentation, I notice that we are now not moving. We have stopped at the mountain station.

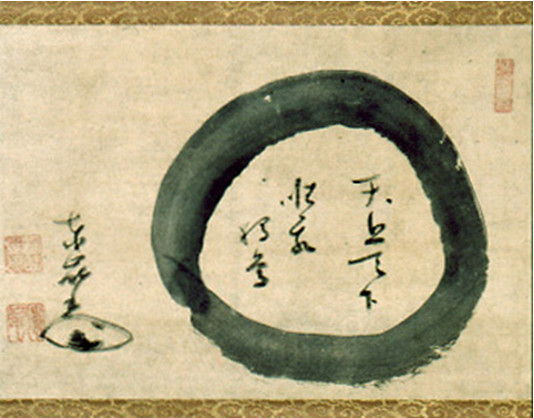

Photographers may prefer to beg forgiveness than to ask permission, but the world will eventually demand payment for the unauthorized gaze by staring back, and will always do so without the photographer's consent. In this case the scrutinizer is a primal, geometric absence, like the painted hoop of an Enso master.

Torei Enji 1721-1792

I experience a flash of illumination, and then the image of myself, transported by refracted light, to the other side of the aperture. The very moment I shoot through it I see the other Mark Fenton shooting towards me. I text my photo to the other Mark Fenton, and instantaneously receive a texted photo from the other Mark Fenton.

But just as +1 and -1 add up to 0, in neither aperture is there a Mark Fenton.

My Railway Guide has gone into the building, either to take a pee, or just to be away from me for a few moments, since I am a) the only passenger and b)I have been leaping from seat to seat willy-nilly, taking photos of bland objects and generally looking like I'm either a terrorist or special needs.

He might now be opening a file on me with the HSR office, in case I become the problem it seems I might.

He returns. We depart. I shoot blindly through the window during the rapid descent down the mountain. Now it's not Ozu I think about

but what is almost the signature of Ozu's contemporary, Akira Kurasawa: The fast tracking shot of a person running through foliage.

Though our journey reveals only the foliage, not the figure,

My memory of the films makes the scene more ominous than it really is. Implanting the thought that someone, probably not a samurai, but rather some contemporary purveyor of violence, hides within these leaves.

Because I'm old, my first experience of movies began as a pre-teen on Sunday afternoons. I would walk to the theatre next to the mall two blocks away, to which I'd been sent reluctantly, probably to give my parents a justly earned respite from the tyranny of childcare. Two hours of sitting and staring at light projected through celluloid in a darkened room. The Sunday afternoon programming of that cultural moment showcased a monster visiting carnage upon train commuters. Spilling the bodies of hard working and hysterical salarymen, like salt from a shaker.

These films did not put me in a good place and the nausea provided by the popcorn's butterlike topping added a low-level Clockwork Orange aversion conditioning to the experience. It wasn't until my late teens that I reclaimed moviegoing.

The decades have moved us through multifarious film media, to the rooftop digital signals mentioned above. A side effect of the information age is the degree of menace we expect to find lurking everywhere, based on the malice that film shows the world to be infinitely capable of.

The next photo is taken on James Street below the level of the railway. This is where I'll end the bus trip component of the essay, since I don't want to give readers too close an approximation of where I live.

It is a sunny spring afternoon but this entrance still feels awfully bleak. I can only imagine how slasher-film-terrifying it would be to enter the train station this way at night, qhen the lights whose filters are meant to convey warmth only spotlight the heartless darkness that all too quickly devours them.

I know that a more dedicated photographer would return at night to document the effect but there's no way you're getting me down here after 8:00 pm and I assume that band of white paint was applied by the city to conceal a graffitied message of violence and hate.

On reaching my stop and disembarking, I thank to my Railway Guide, and wave to the railway guide at him in farewell. I then walk to the auto shop two blocks from my house and pay the astronomical bill for my vehicle and lapse guiltily back into single-occupant motoring.

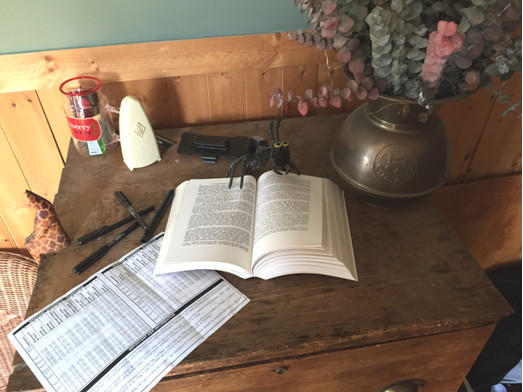

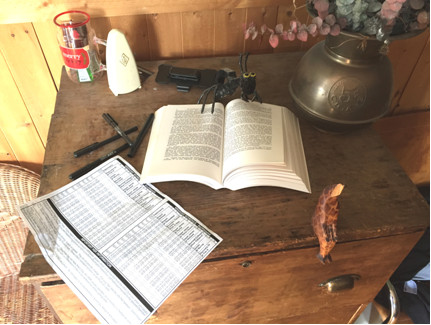

When I arrive home I walk upstairs and stop momentarily at the chest of drawers where a team of black pens habitually congregate to remind me that I always plan to draw my pictures rather than photograph things, but almost never do because it's too much work. Next to them is the still-opened copy of Philosophical Investigations.

I replace the HSR timetable in the exact spot from which I'd collected it

this morning in order to memorize the relevant arrival times and to test my memory against it, if that test could possibly have meaning to anyone other than Wittgenstein now that the journey is done.

(I'm fully aware that the relevance of the Wittgenstein quotation is tenuous. Its continued existence from first draft through to published essay is due mostly to how long it took me to find the dimly remembered proposition, and my reluctance to accept the search as time invested without payoff.)

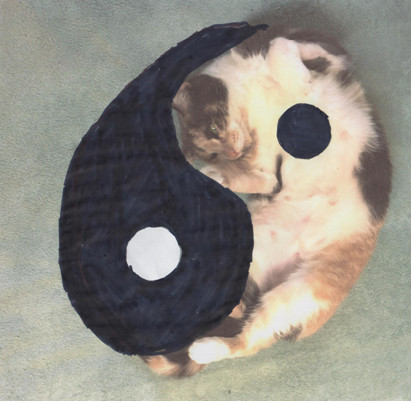

I then move from the chest of drawers to re-examine the cat/meatloaf problem, which has by now unwound itself such that it is now neither a cat nor a meatloaf

but rather a yin yang.

And to this end I go at it with the pens I can now feel justified in having bought, and some type-erase.

While I make no claims to any artistic merit, this vigorous and satisfyingly physical process brings the conflicting forces of the journey into harmony. I might take the bus home again sometime. Four times longer than driving but better both for the environment, and for the art of looking.

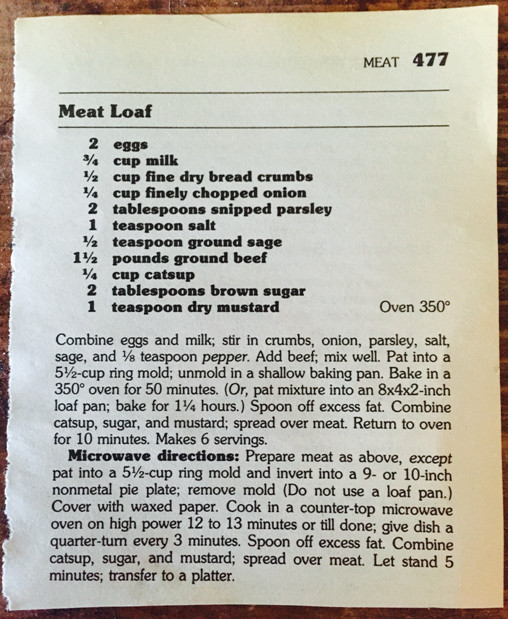

I have never made a meatloaf. I recall my mother making them when I was a child but she hasn't answered my request that she text a photo of her recipe (she might be concerned about the manic urgency of such a text from an adult son who should have more important problems, and perhaps the delay is due to consulting professionals on how to respond.)

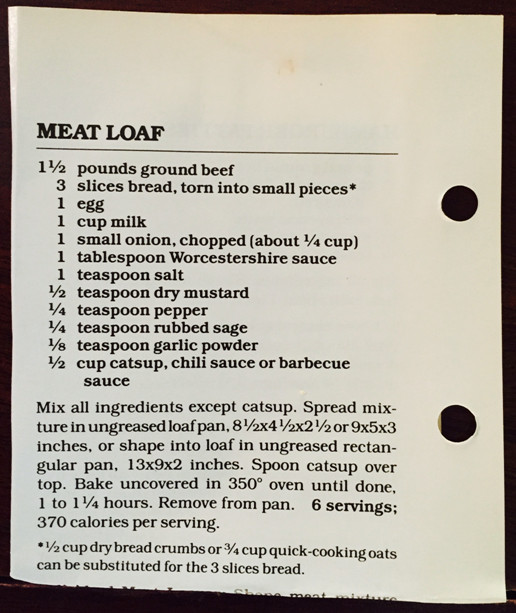

An informal survey tells me that my readers appreciate seeing recipes in these articles. So here are two meatloaf recipes clipped from very old books. (So far I've discovered no recipes in Philosophical Investigations. Not a one. No wonder it's not flying off the shelves at Chapters.)

Figure 1

Torn from Better Homes and Gardens New Cook Book (I didn't bother to check the pub date but I think I got it in 1991.)

Figure 2

Betty Crocker's Cookbook (Ibid pub info. Though here I didn't have to rip the page because the pages were assembled in a binder with an easy ring release. [Thanks!] )

Searching the internet I discovered that a sizable community prepares meatloaf for dogs as an alternative to store-bought dog food. Invariably these pet recipes demand exclusively organic ingredients and are far healthier than the antiquated recipes for humans displayed above.

And here, finally, is an image that illustrates the limitless potential of a pet word that appeals to me for non-utilitarian reasons.

Figure 3

By redmike (registered) | Posted June 10, 2015 at 09:44:59

cool article. weird thing happened while reading it. my inner reader switched from my personal cadence inflection and tone to that of belfast film maker historian visionary mark cousins. i stopped myself and asked "why all of a sudden is mark cousins in my head?" something about your synatx struck me as very cousins, so much so that my inner voice was replaced by his. then the refernce to yasujiro ozu. ozu is one of cousins fav directors, studying writing and speaking to his work often. anyway, again, cool read.

By Skaistalelde (anonymous) | Posted June 10, 2015 at 11:54:56

This essay,like Delft, is stunningly beautiful. Like Wittgenstein, brilliant. No subtlety escapes the mind of Mark to be knitted together with countless other details. Just think if he took on the ENTIRE WORLD! Circle, circle, circle. Stealthy as a cat, no, an sleeping cat, arguably even stealthier. Hey! Hamilton is so lucky!

By mdrejhon (registered) - website | Posted June 10, 2015 at 12:49:33

The furry ball doesn't look like a cat anymore if you obscure a few millimeters of the top edge of the "cat ball" (to hide the cat's ear). All you see is a ball shaped thingy, and if your eyesight is poor or colorblind, it could very well be a pizza pie on the floor.

By bmitchell (anonymous) | Posted June 11, 2015 at 16:13:57

Mark, "you took the words right out of my mouth". (Meatloaf)

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?