The real paradox to parking in a downtown core is that there can never be enough desirable spots.

By Chris Higgins

Published January 20, 2015

Parking, one of the most mundane issues, also happens to be very critical for a host of things, from transportation demand management to urban development and redevelopment. How we view parking is also reflective of the vision we hold for our city.

Last week, I had the pleasure of attending the 94th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board in Washington, DC, where I had the honour of presenting a paper as part of the 'What's Going on in Local Mixed-Use and TOD Environments' session.

At the session I witnessed Professor Daniel Hess from the University of Buffalo present on some of the positive changes occurring in Buffalo with a particular focus on the city's new parking policies.

The cities of Hamilton and Buffalo have much in common. Both have an economic history rooted in manufacturing, both have seen suburban growth and inner-city decline, and both are in the early stages of new urban development and revitalization.

But recent developments in Buffalo have pushed the city towards some of the most progressive policies in support of urban development and there is much we can learn from the leadership being displayed by our neighbouring city to the south.

The City of Buffalo has undertaken the most comprehensive update of its zoning by-laws to occur in 60 years. Called the Green Code, the overhaul of the city's comprehensive plan and zoning is designed to codify and put into action the city's four core planning principles: "fix the basics; build on assets; implement smart growth; and embrace sustainability."

There is a great deal we can take from the Green Code for Hamilton, but one of the most interesting aspects is the city's change to parking policy.

The Green Code makes an important change to how parking is supplied in Buffalo in line with the city's four planning principles. Instead of requiring minimum amounts of automobile parking for new development and redevelopment, the code has replaced mandatory parking minimums with one simple but powerful sentence:

The provision of off-street vehicle parking is not required.

In one fell swoop, the City of Buffalo has freed its parking policy, preferring to let the market decide how much is required.

This change is significant for two reasons: the first is its effect on urban outcomes, while the second is a larger statement on the underlying philosophy that has lead to this outcome.

First, the abolishment of parking minimums is being championed as a tool to incentivize urban renewal. Building parking can be very expensive. In the book Edge City from 1991, Joel Garreau estimated that the cost of a single surface parking space is $3,000 (inflated to 2014 dollars) not including the cost of the land. In contrast, a space in an above-ground structured parking garage is about $7,500 while a below-ground space costs $30,000 - ten times that of a surface space.

These numbers pose a significant cost for developers, particularly in softer real estate markets such as downtown Buffalo. There, the city's requirement for a minimum number of vehicular parking spaces was seen as a roadblock to spurring new development and redevelopment in the urban core, where new projects would necessitate structured or underground parking or the purchase of neighbouring properties.

Such requirements drive up the cost of for developers, even if there is an ample supply of existing parking lots nearby.

The second and larger reason is the statement that revisiting the city's parking requirements makes about the state of past and present urban planning in Buffalo.

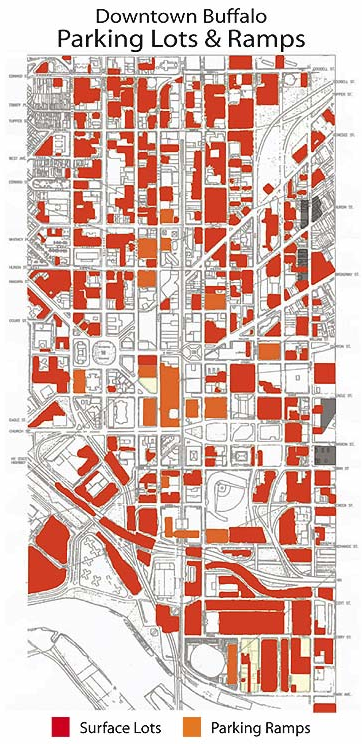

Like Hamilton, Buffalo has a wealth of parking supply in its downtown core. However, as the picture below demonstrates, the sheer scale of hollowing-out that has occurred over the past several decades is staggering.

According to the 2009 study from which it is drawn, more than 50% of the city's downtown land area is dedicated to surface and structured parking (Buffalo isn't alone in this trend - take a look at Houston in the 1980s).

Digging into Buffalo's parking story, I came across this passage as part of a post by planner Chuck Banas. The post is in response to a news article that argued for the need to better manage parking supply in Buffalo's downtown core.

However, it is remarkable for truly capturing the heart of the issue, specifically the failure to understand the strengths of density and urbanization on the one hand, and the desire to make this density more hospitable to the personal automobile on the other.

Because I can't capture this tension between urban and suburban any better myself, I will just repeat it in Chuck's words:

"The dominant theme in the [parking] report is that too many entities are involved in city parking, creating 'shortsighted' and disjointed management." This much is true. But one quote in particular stands out:

"'Downtown can't begin to compete with suburban office parks without convenient and affordable parking,' said Schmand, whose nonprofit agency represents the interests of downtown stakeholders and residents."

To the uninitiated, this may sound reasonable, except for one thing. Downtown can never compete with suburban office parks on the basis of convenient and affordable parking. To compete successfully on that basis would mean the destruction of all of downtown's remaining (and emerging) value.

By definition, downtown can never out-compete the suburbs on suburban, automobile-based terms. By necessity, parking takes up a tremendous amount of land, creating lots of dead, open space, which the suburbs have plenty of. In fact, that's the suburbs' main asset: lots of open space. A city's main amenity is not open land, but density, walkability, a diverse mix of uses, and the quality of the streets and other public spaces. These are the areas in which the suburbs cannot out-compete downtown. These are things cities like Buffalo need to focus on to be successful.

So, if it is evident that an urban environment can never offer as good a "suburban product" as the suburbs can, then why do we continue to play that game? Clearly, the prevailing value system is upside-down. The city's current strategy is irreconcilable with what downtown currently is, and what the community wants it to become. We've got to find a way to break out of this vicious cycle and change this self-defeating paradigm. This requires leadership.

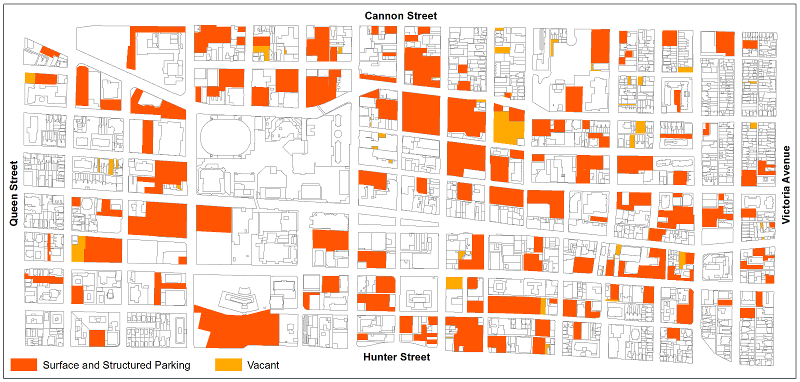

This prompted me to embark on a quick study of parking in our city. My analysis reveals that approximately 24 percent of the city's downtown land area (excluding streets) is dedicated to surface and structured parking.

Adding vacant parcels, some of which would have been parking had the city not imposed a moratorium on new surface parking lots, brings the total up to 26 percent. This is exclusive of other underground parking garages, such as the one under Jackson Square.

Downtown Hamilton Parking (click image to view larger

While not nearly as bad as Buffalo or Houston, one-quarter of our downtown core - what should be the city's most productive land - is dedicated to the temporary storage of vehicles that spend the vast majority of their time sitting empty.

What's worse is that that the City of Hamilton is actively exploring opportunities to build new structured parking in the core on prime land, such as the corner of King and Bay.

What should we do about it? There are three solutions.

Just as in Buffalo, the root of the issue is a planning paradigm based around the personal automobile, and in many ways this paradigm continues. With one-quarter of the downtown dedicated to surface or structured parking, one can question the city's exploration of more downtown parking.

This arose out of a previous study [PDF] by the MMM Group that argued the downtown core would need even more parking in the near future, even with occupancy levels at only 68% at peak periods, and overall occupancy rates down 10% since 2005.

Greater downtown parking supply is fundamentally at odds with what should be our vision for Hamilton's downtown core. We too need to realize that the strength of a city is in its density.

In economic geography this is called agglomeration economies. People and firms see a benefit in density. For firms, density means suppliers, services, employees, and even competitors are located close by. For employees, density means greater life and work opportunities, more amenities, and less time and money spent travelling between them.

In North America, a resurgence in urban density is being driven by the millennial cohort, which has shown lower levels of automobile ownership and driving, higher transit use, and preferences for urban living.

Likewise, agglomeration economies are the foundation of the human capital, creative, and innovative economy and the primary reason why we see people and jobs located in the downtowns of cities all around the world.

Considering these factors, trying to suburbanize the downtown core through greater parking is essentially applying industrial thinking to a post-industrial urban economy.

Similar to Buffalo's old zoning code, part of the hollowing-out of downtown is an outcome of our zoning by-laws that require parking minimums based on the use of the property and its presence within or outside the downtown zone.

In the downtown, these range from 1 space for each residential dwelling unit (in excess of 50 m2 or 540 ft2) to one space for every 50 m2 of most commercial developments (in excess of 450 m2). Serving the needs of cars instead of people downtown has been codified into our zoning by-laws.

Instead of mandatory minimum parking levels, Hamilton should institute parking maximums for the downtown core. This is a popular and effective cornerstone of Transit-and Pedestrian-Oriented Development plans around North America.

Like Buffalo's market-based parking, such a policy frees developers from the necessity of structured parking when developing or redeveloping sites downtown. However, maximums ensure parking is capped to achieve broader transportation and land use planning goals in the downtown core, such as solution three below.

Transportation modes are really just tools to accomplish the job of moving people. Given their space requirements, cars will always generally be the wrong tool for the job in dense urban areas. This is where higher-order modes are at their best.

This leads to the third solution, which is to shift parking supply to outside of the downtown core as part of a comprehensive multi-modal land use and transportation strategy. In Calgary, city planners made a conscious decision decades ago to support their investment in LRT by limiting parking in the downtown core and building park-and-ride lots at suburban C-Train stations.

Our LRT report [PDF] for the City of Hamilton found that this policy has worked wonders - LRT ridership is the highest in North America and the transit modal split to downtown is greater than 50 percent, a great achievement unmatched by other LRT peers in North America - and in car-friendly Alberta, no less.

Hamilton is forecasted to add 90,000 jobs over the next 16 years, and is required by the Province to intensify its downtown core to an average density of 250 jobs and people per hectare.

The MMM Group was right in that new growth will increase demand for greater access to downtown, but their prescription is wrong. Continuing to supply greater levels of parking in the downtown core in Hamilton will just handicap rapid transit here in the future.

One has to only look at Buffalo's parking map to understand why the city's LRT has failed to attract a significant number of riders since it was built.

In the end, the real issue for parking critics is of course whether there is enough desirable parking, spots in locations that minimize the walk between the parking space and where drivers want to ultimately go. But the real paradox to parking in a downtown core is that there can never be enough desirable spots.

To finish, I return again to Chuck's wisdom:

There's my old saying, which I've oft repeated: Like all cities, we really have one essential choice; we can have a vibrant downtown where everyone complains about parking, or we can have a dead downtown where everyone complains about parking. If you think about it, that's the only choice. Really.

See also:

By jason (registered) | Posted January 20, 2015 at 17:20:02

Looking forward to Andrew Dreschel's article explaining how you have written a new piece advocating for dozens of new parking garages downtown.

Really though, great piece. Bang on with the reference to Buffalo and their recent policy changes.

By Montreal Gary (anonymous) | Posted January 20, 2015 at 18:23:37

Having moved here from Montreal 5+ years ago, this article is bang on.

Born and raised in MTL, I've always lived in the central core (Le Plateau, mostly).

As a result, I don't drive and have never had a license. Density builds neighbourhoods and community. Living on James North, I still don't need a car but, it still has a way to go.

By higgicd (registered) | Posted January 20, 2015 at 18:43:35

A little side anecdote I cut from the already lengthy article - at the committee meeting I attended someone noted that there was one single surface parking lot left in downtown DC, right by the conference centre, and that next year it will be replaced with a Conrad hotel. Someone jokingly wondered aloud if someone would step in at the last minute and stall the project by getting the parking lot a heritage designation.

Seems that surface parking is going extinct in many cities. We can only dream of the day that occurs here as well.

Also, anyone remember the last time we had a comprehensive review of the city's zoning by-laws? I think its time for our own Green Code process. Like parking this is a bit mundane, but is the type of foundational thing that stands to truly get us 'rapid ready' and have a measurable impact on how we capitalize on the trends towards urbanizaiton that are occurring to revitalize our core.

By fmurray (registered) | Posted January 20, 2015 at 19:30:28 in reply to Comment 108080

Brian McHattie, if he was elected as our mayor, was planning to analyze zoning as it related to the B-line LRT.

I don't know much about zoning, but understand it is long past time for a re-examination of this to encourage more commercial investment.

By DowntownInHamilton (registered) | Posted January 20, 2015 at 18:51:10

I am all for multi-level parking garages where something like a 5 level garage will replace 5 individual lots. If we're just adding more because some business wants to make money off the 9-to-5'ers, then tell them to take a hike.

By Dylan (registered) | Posted January 20, 2015 at 19:36:47

Is there anything more hideous in a downtown than a surface parking lot? I say build more garages, not to increase the number of overall spots, but so that we can be rid of the multitude of surface level lots.

I think there's a catch 22 here. Governments won't spend on future infrastructure; they will not fork out funds for transit without an already intense density. To attain the desired density that apparently must precede their spending on transit, we build freeways, make our roads car friendly, and make parking ample. This results in a downtown no one wants to be in outside their 9-5, if even that. And after we've spent our tax dollars on these frivolous ventures we're left is the same place we were at the beginning.

I hope there are enough good people in office with the forethought to avoid this density..I mean destiny.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?