If this preamble is menacing, that may be because it's the first of a planned series on the more extreme motoring challenges to be found in the Hamilton area.

By Mark Fenton

Published January 20, 2015

I stand on a Sherman overpass looking onto a further Sherman overpass.

The perspective suggests an infinite regression of pedestrian (ped) and motoring (pod) terror.

It is a cold, January day. Later I discover that 43 years ago to the day, American poet John Berryman stood on a similarly cold bridge in Minneapolis, waved casually to a passerby, hopped the rail, and became whatever his spirit did or didn't become.

If this preamble is menacing, that may be because it's the first of a planned series on the more extreme motoring challenges to be found in the Hamilton area.

The series doesn't pretend to be comprehensive, nor is it in any way endorsed by the Ministry of Transport, any driver training organization, or even, necessarily, the editorial staff of RTH. I'm simply describing my personal motoring challenges and proposing strategies to meet them.

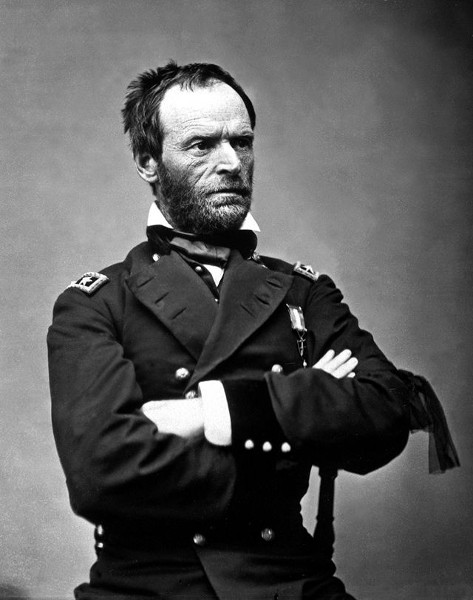

I had lived in Hamilton for 22 years and only today assembled the nerve to attempt the Sherman Cut. The very name invokes an image of General William Tecumseh Sherman

and the swath of carnage he cut through the Confederate states during the civil war. In actual fact the Cut was named for Clifton and Frank Sherman, cofounders of Dofasco. With images of industrial forging, molding and slicing up sheet metal for sale to industry that includes automobile manufacture, they supply just as apt a metaphor. These accidental or intentional eponyms convey to me that the Sherman Cut is not for the squeamish.

For years I'd looked upon its borders

solely as ped traveler, imagining the day I would summon up courage to attempt it pod.

And that day would be January 7, 2015.

I park a block away, steeling myself up for my virgin pod journey. Note the redundancy of the signage across from where I'm sitting.

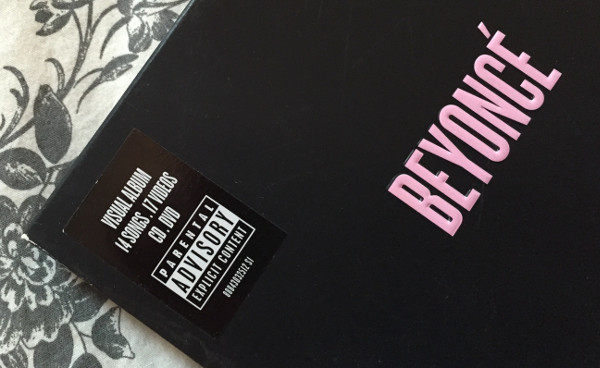

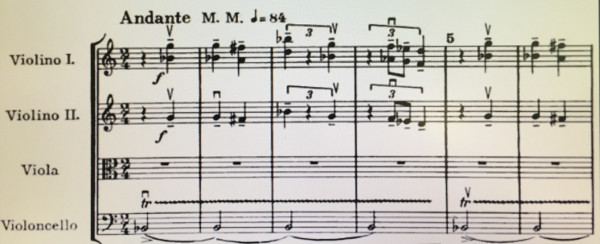

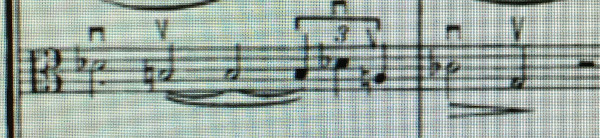

The upper arrow is purely directional. The lower arrow, while not contradictory, is slender and pointed, aspiring to a goad that forces me painfully towards the inevitability of the Cut. Still in my car I prepare myself with Janáček's String Quartet No 2. Don't roll your eyes. I don't only reference classical music in these essays. And in fact, I wanted to play last years' Beyoncé CD, legally purchased and complete with parental advisory.

(My parents weren't present when I bought it. Standing in the checkout line I texted them my intention and took their messaging silence as approval.)

Not owning, say, a state of the art 2015 BMW, but rather a 12 year-old Toyota Echo, the motor of the vehicle's CD player is incapable of handling Beyoncé at below zero temperatures, so instead I'm reduced to playing what's cued up on my MP3 player, which simply happens to be Janáček's String Quartet No. 2, a composition I consider no less sexy than Beyoncé. (Readers will no doubt be divided on this judgment. Feel free to post your thoughts on the matter.)

Enter the cello at fortissimo playing an anxious and extended trill with which the composer clearly intended to represent my central nervous system. A quarter-note later in come the first and second violins playing emphatically in parallel motion, with which duo the composer clearly intended to represent the murderous two way traffic of the Sherman Cut.

There is no viola for some reason. Oh. Now there is. Enter the viola at bar 9, pianissimo. The violins and cello drop away. Clearly the viola is meant to represent my personal journey through the cut.

Then, unexpectedly, at bar 15 the viola hits fortissimo and plays the same trill the cello was playing at the beginning.

This is not helping.

I turn the ignition, shoulder-check, move forward, turn, and enter the Sherman Cut. Janáček's wispy viola bounces back and forth in the rough trade of cello and violins, somehow maintaining dignity against this unrelenting assault. I and my vehicle descend between the passage's ice-clad walls.

I turn appropriately before the escarpment plunges. Through a long series of negotiations on the escarpment I return to Concession and Sherman and park in the very spot where minutes before I steeled myself up for the pod journey.

In ped mode, I can gain a more relaxed and thorough assessment of how pod would move safely into the cut. A more savvy traffic engineer would probably have assessed the multifarious traffic signage (see below) as ped before executing it pod, but I have a) no such foresight and b) just enough journalistic integrity to adhere to the chronology of the photos and embarrass myself.

I remove the MP3 player from its dock and attach ear-buds in order to continue to use Janáček Quartet No. 2 as a unifying soundtrack to my essay.

Below are two photos which give an overview of the information pod is expected to process on final approach. Keep in mind that all of this information hits pod in the space of 10 metres. I'm not mathematically deft enough to handle the calculus of yielding and then accelerating, but given the slowdown for general confusion and cross traffic let's assume an average velocity through the photographed zone of 30 km/h. My math says the motorist has less than 10 seconds to digest the information. (I came up with 8.3 seconds but I'm hesitant to show my work.)

Review these photos before setting out. For less visual learners here's a list of pertinent information in convenient bullet points.

Yield sign. (x2)

Sign indicating the motorist STOP CLEAR OF GATE rather than, say, proceeding until the gate curtails the forward motion of the car or alternately, before the vehicle crashes through the gate. (I'm flashing on a Fiat crashing through a checkpoint gate in some cold-war-era thriller.)

The gate itself. (The one the motorist was just warned to stop clear of.)

A sign indicating the motorist not be a big truck.

A sign indicating the motorist not be ped.

A sign indicating that the motorist not be a falling rock, but that if he/she must be, that that possibility be advertised to passing vehicles.

A Hamilton in Bloom promotional sign with corporate sponsorship branding beneath it. I'm tempted to call this two signs based on the diversity on information. Yes. I. Know. This is an ad, not motoring information. Here's the thing, though: it's mounted exactly below STOP CLEAR OF GATE and in exactly the place a motoring-critical sign would be placed, and the thorough motorist will need to assess its relevance and then dismiss it as irrelevant and this adds a few more microseconds to some layer of whatever contrapuntal gymnastics the motorist's mind is capable of. (A shorter way of saying the above is that you need to read the sign to know that you don't need to read the sign.)

The biggest and most critical sign. DO NOT ENTER 3:50-6:10 PM MON-FRI RIGHT TURN ONLY. The motorist will also need to process the series of lights above the sign which vaguely resemble the start codes for a drag race. I'm assuming conventional red/green motoring symbolism is involved. If any reader has info on the nuances of these lights please post a comment.

My last bullet point refers not to a sign but to an implied visual reference. The need to consult a timepiece on the person of the motorist, or better still on the dash of the pod, in order to confirm that the motorist is entering the Sherman cut outside the 3:50-6:10-Mon-Fri window. Or, should the motorist be inside the 3:50-6:10-Mon-Fri window, to heed the last resort instruction to divert right and avoid certain death (rather like the eject option in a fighter plane).

I count nine distinct visual references the motorist is expected to make eye contact with before hurling him/herself into the abyss that is the Sherman Cut. About a second for each. At the same time the motorist has to make sure the cross-traffic is clear at the yield, which is ... um ... the most critical visual assessment to make in order to avoid terminating his/her and/or another person's/other persons' life/lives. (While the forgoing sentence is syntactically rigorous as far as I can tell, it may well be the most annoying sentence ever published in RTH. The portion of my brain responsible for linguistic clarity has clearly been exhausted by attention to traffic signs.)

An advantage to being ped here is that I can safely turn 180 degrees and assess information that might be relevant to the setting. That's when I notice the billboards.

Surely it isn't lost on anyone ascending the Sherman Cut and seeing the billboards that this would be a very logical place to sustain a debilitating injury. Some say the brain erases the memory of events immediately preceding trauma. Others say that the last moments before a crash are intensely vivid. Should you be in the latter category, the positioning of advertisements for firms specializing in personal injury law is strategic.

I'm particularly impressed by the one depicting a timeless image of caring and intimacy and commitment. Showcasing the paradox of a culture coldly disengaged enough to do the math that makes the insurance industry fiscally viable, yet civically compassionate enough to know the value of doing so.

I know such thinking is naïve, but the nostalgic side of me longs for a simpler time. A time without billboards. A time when motor vehicles were for the privileged few. A time with few institutional structures of care, yet a time when people might simply have nurtured one another. As I think these thought, lush chords of the Janáček Adagio are taking me back to Janáček's Czechoslovakia.

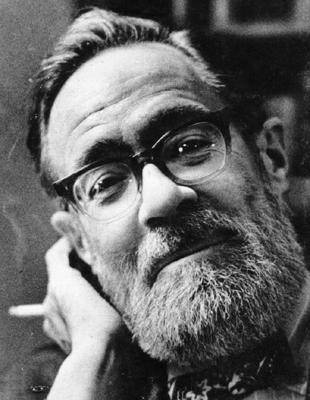

I crave an oasis amidst the bombardment of 21st century traffic and insurance structures. And so standing in the grass space by the Sherman Cut entrance I Google information on the life of Janáček, looking not so much for the artist himself, as for a sense of the artist's time and place and community and loved ones. Here is the most beautiful and nurturing image I come across.

An image unmistakably of Janáček's world, and at the same time utterly timeless.

An image which harmonizes strangely with the wedding photo on the billboard, just as the harsh chords of the first and second violins harmonize strangely with the melody of the viola.

I am now well past the half-way mark in Janáček Quartet No. 2. As I see the cars descend I hear a mournful descending line on the viola at a slope similar to that of the Sherman Cut.

I realize that I associate this instrument with my own journey in vain. It simply reflects the starkness of the Hamilton Mountain at this particular junction. The light is silvery. The air is thin and Janáček Quartet No. 2 is the perfect soundtrack.

To return to my car, I walk along Concession Street, Northward advancing on the escarpment. I am struck now by the pod ramp that rises up to the emergency entrance of the hospital.

Like the trench that enclosed me in the Sherman Cut and created a jittery counterpoint between death drive and pleasure principle, so the welcoming tunnel past the Emergency entrance opens onto void, terror, annihilation. I feel compelled to hurl myself into this negative space.

But as I enter the enclosure the void disappears.

Looking down from the hospital ramp on the other side of the entrance the view is tense, but not ominous.

Though I imagine the turn at the T-intersection might be nerve-wracking at night.

The thought of driving the Cut in darkness and poor road conditions makes me think of lines from John Berryman

A cold night.

On Outer Drive there was an accident:

A stupid well-intentioned man turned sharp

Right and abruptly he became an angel

Fingering an unfamiliar harp,

Or screamed in hell, or was nothing at all.

Anniversaries are arbitrary things, but they're an excuse to remember.

I discover further images of the Washington Avenue Bridge in Minneapolis, the bridge from which Berryman forced his own end.

The structure is more complex than I first realized. Bordered by two outer pedestrian walkways is a cozy enclosed passage,

And yet in my mind's picture of that narrow enclosure, death materializes

as witness to Berryman's final gesture.

My gaze rises upward and beyond the Cut. To the lower city where thousand eat and sleep and reproduce and raise their children and work and love and are cared for in their final days. It could be the establishing shot of every essay I've posted here. While I'm in no position to evaluate my intelligence or lack of it in regard to my photo-essays, I sincerely believe they describe the journey of a well-intentioned man.

I move downward and onward and back to my car and drive carefully home.

By Been there done that (anonymous) | Posted January 20, 2015 at 20:14:21

My grandparents lived across from the Sherman Cut from the '50s to 1986. My cousins, siblings and I would walk to their house, crossing the cut every time we went, probably from the time I was 6 or 7 years old. We would run to their front porch every time we heard the bells go signalling the lowering or raising of the arms directing the flow of traffic. Playing on the greenspace on either side of the access would keep us occupied for hours out in the sunshine.

I have driven up and down the access without issue ever since I first got my license, having observed the rules for many years as a pedestrian and a passenger in my parents' car. I think the Sherman Cut is probably the most efficient access, helping drivers traverse the escarpment and avoiding heavy downtown traffic. I understand people are hesitant about using the access, but it's a great traffic tool. And I have fond memories of playing on the park space beside it as a child.

It is a Hamilton icon - don't be afraid of it, celebrate it :)

By Mark Fenton (anonymous) | Posted January 20, 2015 at 20:48:07

Hi Been There Done That

If I'd've been there, you know I'd've been the kid down the street who wanted to tag along with you kids and watch that barricade go up and down like a protective arm rattling its bling. I love when something I write elicits nostalgia. Thanks for reading. :) Mark

By notlloyd (registered) - website | Posted January 20, 2015 at 20:58:43

Love the Sherman cut. Great way to cross town without clogging up residential arteries and there are no stop lights.

By Liz (anonymous) | Posted January 21, 2015 at 10:01:52

It still amazes me how many drivers still come to a full stop at the top of the cut. I drive it twice a day and come thisclose to an accident at least once a week.

By Sally Garden (anonymous) | Posted January 22, 2015 at 16:22:19

"I Google information on the life of Janáček, looking not so much for the artist himself, as for a sense of the artist's time and place and community and loved ones. Here is the most beautiful and nurturing image I come across..."

This paragraph is followed by a historical image of a woman and a young child, followed in turn by its contemporary equivalent and the comment: "An image unmistakably of Janáček's world, and at the same time utterly timeless."

Alas, the composer's world and work also included quite different experiences.

I remember very well huddling in the second balcony at the former home of C.O.C., tears flowing, during the impossibly redemptive finale of Jenufa.

From the synopsis, available on the Met's site:

" ACT II. While everyone thinks she is in Vienna working as a servant, Jenufa has remained hidden at home and given birth to a boy. Her proud stepmother cannot bear the shame and has sent secretly for Števa. After giving the girl sleeping medicine, she tells him about the baby and kneels before him, begging him to wed Jenufa and claim his son. But he refuses to take a disfigured bride... Next Jenufa's distraught stepmother turns to Laca, who is eager to marry the girl but so taken aback to hear about her baby that Kostelnicka on an impulse pretends it is dead. There is only one way out for her now, she feels. Taking the child, she heads for the frozen millstream to drown him. When Jenufa wakes, she prays for her child, but her stepmother returns to tell the girl she has been in a coma for two days, during which the baby died..."

Community can also be a many-tentacled tyranny. In opera it usually claims the lives of women, although Jenufa does escape with hers. In the world, it is a little different, but every time a tentacle is cut, it seems to regenerate again.

Oh. Nice piece, by the way.

Our technical capacity to mediatize existence ie grab from the communal respository all sorts of things to embellish acounts of the associative paths of consciousness is becoming another puzzle for an already pretty puzzled bunch of primates. Are we being augmented or diminished by being pushed further out of immediacy? The problem keeps getting sharper and sharper as our intellectual prosthetics get better and better. I don't think that there is only one vast text which is circulated by readers and writers between which there is not much distinction. In an "unilluminated" text, ie one consisting in print only,the work of the author in making the subjective objective ie putting the thought in writing, is much greater than the work of the reader in making the objective subjective again. But I wonder if the ratio is changing. Being able to paste in an illustration on the fly, rather than describing a black and white photo of mother and child ie evoking it in the reader's mind is less work, but then again for the reader to be satisfied with a composition, it has to have at least as much "play" in it for them as the print-only piece does, which is what this piece seems to achieve. It is a kind of cinema. But also digressive and self-correcting in the way that oral accounts are.

Anyway. I would also suspect Mr Fenton of harbouring satirical inclinations, given the traffic obsessions of his patrons, were if not for his reassuring remark that he is a "well-intentioned man." I have heard that it is possible to be both well-intentioned and an ironist, but surely not here in Hamilton, last bastion of the Folk.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?