According to a new C.D. Howe study, the government's GTHA congestion cost estimate does not include the opportunity cost of missed chances to match skills with jobs, share knowledge and conduct mutually beneficial exchanges.

By Ryan McGreal

Published July 12, 2013

The Ontario Government has been arguing that traffic congestion in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA) costs the region $6 billion a year in lost productivity and environmental and health costs. Metrolinx has proposed an investment strategy that will raise $2 billion a year to pay for new transportation infrastructure across the GTHA to reduce those costs.

However, a new report [PDF] by Benjamin Dachis of the C.D. Howe Institute argues that the annual cost of congestion is actually $1.5 billion to $5 billion higher, due to the opportunity cost of missed chances to match skills with jobs, share knowledge and conduct mutually beneficial exchanges.

In economics, an opportunity cost is the cost of a missed opportunity when one choice is made that precludes an alternative choice. If you have a situation where you can do either X or Y but not both, the opportunity cost of choosing X is the cost of not being able to choose Y.

According to the report:

[The existing studies] ignore the positive effects of relationships among firms and people that are among the main benefits of urban living. These urban agglomeration benefits range from people accessing jobs that better match their skills, sharing knowledge face-to-face, and creating demand for more business, entertainment and cultural opportunities which, in turn, benefit other people. When congestion makes urban interactions too costly to pursue, these benefits are foregone, adding significantly to the net costs of congestion. For the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area this report estimates the additional costs to be at least $1.5 billion and as much as $5 billion per year.

So-called "urban agglomeration benefits" are among the essential economies of cities, qualities of urban form that make people living in them more productive: economies of scale, agglomeration, density, association and extension. Together, these urban economies simultaneously increase the size and diversity of markets, reduce the cost of production, and increase the rate of innovation.

The urban agglomeration economy is a positive feedback loop in which companies in a given industry tend to cluster together, both vertically (up and down supply chains) and horizontally (among competitors). While it may seem that clustering would increase competition and drive prices down, the positive feedback effects of better knowledge dissemination, a larger, more diverse pool of employees, investors, suppliers and so on more than compensate.

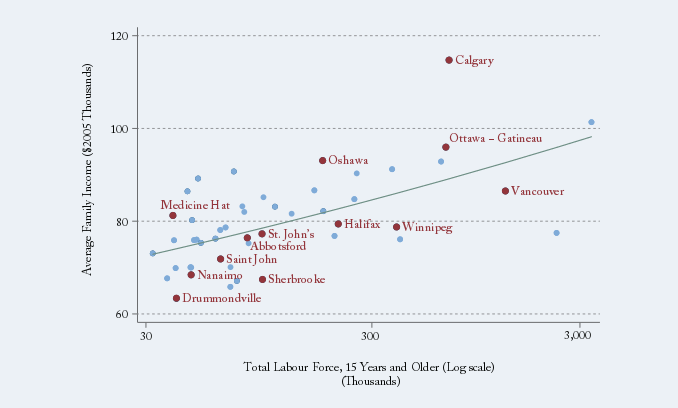

Chart: Income and Size of Labour Force by Census Metropolitan Area, 2006 Census

A cluster is also better at attracting customers. In the same way that a Starbucks opening across the street is good news for an independent coffee shop because it exposes the independent shop to more customers, the economy of agglomeration creates a larger, more robust, more well-appointed market that produces a positive-sum outome.

Even the competition turns out to be a net benefit, because it incentivizes companies to innovate to create higher value, lower cost products.

According to the Howe study, these "urban agglomeration externalities" are not included in the Ontario Government's estimate of the cost of congestion.

Because congestion raises the cost of putting people across the region in contact, people choose less valuable alternatives and the economy as a whole has to forgo the value that comes from agglomeration economies. The opportunity cost is the difference in value between what people choose and what they would choose if the transportation system was more effective, which Dachis estimates at between $1.5 and $5 billion.

According to Dachis, the opportunity cost of lost urban agglomeration economies due to traffic congestion is a negative externality that should be taken into account.

In economics, an externality is a cost or a benefit that accrues to society as a whole rather than to one of the parties to an economic exchange. A positive externality is a benefit that accrues to society, whereas a negative externality is a cost that accrues to society.

For example, education is a positive externality because, while getting an education increases the value of an individual who is educated, society as a whole also benefit from the higher productivity of a more educated population.

Traffic congestion, on the other hand, is a negative externality, because each additional person who decided to drive increases the delay of every person who is driving. (Next time you are sitting in traffic fuming, remember that you are part of the problem.)

In transactions with negative externalities, people tend to over-invest because some of the costs fall on others. Conversely, in transactions with positive externalities, people tend to under-invest because some of the benefits fall on others.

One way that governments can produce more effective markets is to take externalities into account through public policy. For example, public education is a good policy because the public cost of education, paid by tax collection, is more than compensated by the enormously increased overall productivity and buying power of an educated workforce.

For transactions with negative externalities, public policy can levy a charge on the transaction that is equal to the social cost of the externality. One example of this is congestion pricing, which raises the cost to an individual of choosing to drive on a congested highway.

Public policy should favour projects that have a net public good: the overall benefit to society is greater than the overall cost. Dachis notes:

[G]overnment investment often involves projects in which there is an insufficient private rate of return to enable private investment. For pure public goods, such as open-access parks, the environment or national defence, the private returns will be insufficient to incent private investment. However, the broader social returns may be quite large.

Regional transit is a case in point: while a private carrier might not be able to run a profitable transit system, the government may still be wise to invest in one because the overall societal benefit of increased transportation efficiency more than compensates for the public cost of building and operating the system, even when the opportunity costs of taxation have been taken into account.

(This is especially true in a sluggish economy like this one, in which a lot of private capital is essentially parked and higher taxes do not risk displacing private investment.)

Dachis sketches the positive urban externalities - labour market pooling, distribution of knowledge, competition, shared resources and cost-effective amenities - and contrasts the negative urban externalities of congestion and rising land prices.

By investing in regional transit that reduces congestion and allows for the positive externalities that come from urban agglomeration economies, the Ontario Government can actually produce a net economic benefit even when accounting for the increased taxpayer cost of making the investment.

By taking a more comprehensive view of the cost of congestion, the net benefit to transit investment is even higher than the government's existing calculations.

As an aside, Dachis makes a point about optimal road capacity that is particularly relevant for Hamilton:

In order to assess the cost of congestion, it is important that policymakers have an appropriate target for the optimal amount of congestion. Drivers would prefer roads with no traffic at all, ensuring no traffic congestion. However, the outcome would be an inefficient over-expansion of roadway.

In other words, it's a waste of scarce public resources to aim for streets that look like this during rush hour:

King Street between Sanford and Wentworth, looking west (Image Credit: Bob Berberick)

Dachis goes on to note that attempting to address traffic congestion by increasing lane capacity produces a vicious cycle of induced demand.

Increasing investment in roads to the point at which traffic flows freely, in the absence of any pricing, would result in a subsequent increase in demand to the point at which congestion would largely, but perhaps not entirely, return to the previous level. A free flow baseline is therefore only a reflection of road supply, not demand.

Hamilton policymakers, kindly take note!

By Noted (anonymous) | Posted July 12, 2013 at 11:52:49

On the city side, things are completely chaotic as councillors continue to paint themselves as a political body that can’t be trusted to stick with a decision. In the past, I’ve greatly admired TTC chair Karen Stintz for her principled commitment to promoting realistic strategies for building transit, but on this issue she’s merely playing to all her critics who have deemed her a flip-flopper. After finally convincing a huge majority of city councillors to sign an agreement with Metrolinx and the provincial government to build light rail last fall, she’s now openly advocating for parts of that agreement to be torn up.

After next week, council will have sent the message that every other transit line they previously approved can also be reconsidered. Which is good news for the mayor, who still wants to trash most existing light rail plans in favour of a single unfunded subway project on Sheppard.

Queen’s Park doesn’t look much better. The right move on their part would have been to dismiss any changes to signed and sealed transit plans — and instead focus on getting things built. But the Liberal government can scarcely hide that their record on delivering transit is actually pretty lousy. They’ve talked a good game, sure, but in the years since their big, flashy funding commitment, they’ve become masters of breaking promises and delaying outcomes. They’re always too willing to indulge the finicky desires of city politicians — and, each time they do, their spending commitments get conveniently pushed back a few years.

On top of that, the province has never allowed Metrolinx to fully achieve its mandate. When the GTA transit agency was created, the idea was to create a body that could build transit in an environment a few steps removed from the whims of politicians and the instability of election cycles. But politics continues to dominate transit policy, with the looming Scarborough byelection apparently influencing attitudes and Ontario Transportation Minister Glen Murray seeming at times quite content to embrace sudden changes to established plans.

http://metronews.ca/voices/ford-for-toronto/736096/good-transit-planning-gives-way-to-pandering-politics-in-scarborough-subway-debate/

By Pxtl (registered) - website | Posted July 12, 2013 at 12:08:18

And yet whenever we try to make a system that allows people to escape from traffic woes, it's the "war on cars".

The war on cars already happened. Cars lost, soundly defeated by cars.

By Rob (anonymous) | Posted July 13, 2013 at 13:46:27

The congestion issue may be larger, but that congestion in Hamilton isn't something that will be helped at all by the Metrolinx plan for Hamilton (I'm talking LRT). Is there a congestion issue on the B-Line? Not at all. The congestion issues we have are the Linc/403, Red Hill/QEW and the QEW/403 junction.

The Metrolinx plan will not help those pinch points but they certainly will tax everyone in Hamilton to provide a solution to a problem that does not exist while not helping our actual problems.

By Conrad664 (registered) | Posted July 15, 2013 at 13:28:11 in reply to Comment 90221

Very true tell me that in 20 years if its not congested then you willl try for LRT

By AnjoMan (registered) | Posted July 15, 2013 at 10:01:51 in reply to Comment 90221

a) the point of LRT in Hamilton is not chiefly to reduce congestion but to improve public transit in a permanent way - if you read RTH regularly, you will know that there is a mountain of evidence to suggest that LRT lines would be a net economic benefit to the city, even though we don't have congestion problems in the core.

b) The metrolinx plan also focuses on expanding GO train service including all-day GO service to Hamilton as well as electrification of rail lines, which will increase the level of service and also reduce the travel times - these things will benefit Hamilton since they will make it easier for people to commute, not just out of the city but also into the city for work. LRT lines will also make GO services to/from Hamilton accessible for more businesses and residences.

c) The economic costs of congestion on highways not in Hamilton are also paid by many Hamiltonians who routinely drive these roads for work and travel.

In conclusion, the Metrolinx plan will benefit Hamilton both directly and through externalities.

By Rob (anonymous) | Posted July 18, 2013 at 22:00:17 in reply to Comment 90234

LRT net benfits plan was based on a funding model that was before the current Metrolinx is planning to pay for it.

Let's see how the numbers shake out when you include all the extra taxes and fees everyone in Hamilton would have to pay be getting LRT.

The original economic justification is apples and oranges compared to what we're looking at now. How does $1,000 extra taxes and fees for a family of 4 in Hamilton to pay for LRT look to you?

By z jones (registered) | Posted July 19, 2013 at 00:34:19 in reply to Comment 90269

The real question is, how does $1000 extra taxes and fees for a family of 4 in Hamilton to pay for LRT in Mississauga look to you? We're going to pay either way. Let's at least get something worth paying for. Remember there's only one taxpayer.

By banned user (anonymous) | Posted July 19, 2013 at 12:00:26 in reply to Comment 90270

comment from banned user deleted

By Conrad664 (registered) | Posted July 15, 2013 at 14:59:02 in reply to Comment 90234

Oh your wright GO trans QWE 403 407 there we be way to smale for all the cars we will have in 20 years from now

By AnjoMan (registered) | Posted July 15, 2013 at 16:00:29 in reply to Comment 90239

they are too small now already!

By Sigma Cub (anonymous) | Posted July 13, 2013 at 20:47:45 in reply to Comment 90221

The Big Move isn't intended to alleviate current congestion levels, but rather to return to them 25 years from now, by which point current traffic volume will constitute a marked improvement on the intervening vehicular tarpit.

By ViennaCafe (registered) | Posted July 13, 2013 at 15:51:40

Actually, it will. The more people using LRT the fewer people on the roads including the ring road. But thank you for pointing out one way highways across Hamilton are no longer required.

By LOL all over again (anonymous) | Posted July 22, 2013 at 23:42:37

But as has been pointed out time and again on this site Hamilton does not have a traffic congestion problem. We have terrific system of one way roads that moves traffic quickly and efficiently through the city. Toronto on the other hand has terrible traffic problem and needs all the help it can get.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?