The San was the work of the whole city, the collective effort of Hamiltonians of all classes. Surely this place is worthy of designation as a national historic site.

By Shawn Selway

Published May 04, 2013

At a 1952 meeting of supporters of the Mountain Sanatorium covered by the Spectator, more than forty organizations involved in visiting patients, distributing comforts or donating funds were represented. These ranged from the Red Cross to the National Council of Jewish Women, the YMCA, the IODE and the Samaritans. The Visitor books show that the Knights of Pythias and the local Cub Scout and Girl Guides were regulars.

Kiwanis Club of Hamilton: For Tuberculosis Work (Source: Archives of Hamilton Health Sciences and the Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University)

Hamilton has not designated a building under the provisions of the Ontario Heritage Act in five years. As Paul Wilson noted in his recent CBC piece on the San, five of the remaining sanatorium buildings are on the list of properties of historical interest. None are designated.

As a cultural landscape the San is only slightly less significant than the Gore and the bayfront furnaces, stacks and sheds, for at least four reasons:

The San was the work of the whole city, the collective effort of Hamiltonians of all classes, maintained by the annual fund-raising campaigns, bequests of money or property, government grants, service clubs and churches which sponsored the acquisition of particular pieces of equipment and always, numerous individual volunteers, ranging from local amateur entertainers to gift shop salesclerks to the man who was inspired to play Santa Claus.

The terraced "pavilions" are early works of architectural modernism by notable local architects, William Palmer Witton and Hutton and Souter.

The San has great importance in Inuit history. Between 1954 and 1962 about twelve hundred people from the Eastern Arctic passed through Hamilton. (Westerners went mainly to the Camsell in Edmonton, or Clearwater at Ninette Saskatchewan.)

Just as the deprivations of the Great Depression and the bounty of wartime industrial expansion produced post-war social security measures, the logic of the anti-TB crusade led to its universalization.

No jurisdiction could singlehandedly deal with the problem of detecting, preventing and treating contagious TB which involved large scale public health measures, mass screening and long term hospitalization. The logic of interdependence compelled state intervention. In Canada, this culminated in universal publicly funded health care.

Five years before his death in 1902, the cosmically conscious Richard Bucke, ardent Whitmanite and superintendent of the asylum at London, Ontario, included in his Annual report a proposal for the "Care of a Certain Class of Lunatics."

He suggested a small reserve, five or ten miles square, by a river, wooded, and having pasturage, clay beds and a quarry.

Temporary buildings would house a couple of hundred patients, who would proceed to clear the land, dam the river to generate electricity, and use the power to run an electric railway from the central "executive building" to the nearest steam-locomotive line. And so on. Such a community would take forty or fifty years to mature.

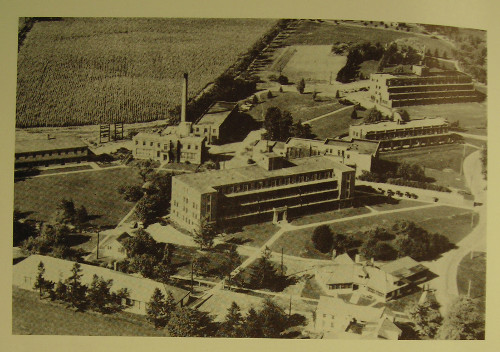

Looking north, the San is in the upper right

Looking north in the above picture, the San in the upper right, some of its farm buildings in the lower right. The year is 1968, just as the farm was being closed out.

The model suggested by sanatoria, of centralized kitchens and laundries serving a large population, was proposed for general application by early twentieth century feminists but seems to have been entirely absent from the social imaginary in the post-war period.

Instead, we got detached bungalows, each with its own kitchen for the preparation of the standard 1,095 meals a year. Plus snacks. Source: Archives of Hamilton Health Sciences and the Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University.

This figure, of the place apart, rural, with a large focal structure, haunted the imagination of the 19th century. Seclusion, involuntary as in the case of hopeless alcoholics or impossible psychotics, or voluntary, as in the case of the radical renovators who established many experiments in communism, entailed self-sufficiency, and this was difficult.

The most successful (apart from that of the Mormons, who are a very special case indeed) was the Oneida organization led by John Humphrey Noyes. Oneida survived by manufacturing preserves, steel traps and metal tableware. But TB sanatoria, unlike asylums or utopian communes, could never operate as work-colonies; they were the reverse: closed parks where patients were admonished to work very hard at not working at all.

Sanholme Farm supplied milk, chickens and pigs to the San

The San was organized as a suburban commune, for maximum self-sufficiency. In addition to providing the patients with milk from about 1913, the adjacent Sanholme farm raised chickens and pigs - up to 500 at a time.

A 1948 Spectator article listed the elements of a typical meal for eleven hundred ordered by Marion Evans, chief dietitian: 6 hogs, 65 gallons of soup, 9 bushels of turnips, and 180 pumpkin pies. Source: Archives of Hamilton Health Sciences and the Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University.

In 1863 the British anatomist John Hilton published "On Rest and Pain, a Course of Lectures on the Influence of Mechanical and Physiological Rest in the Treatment of Accidents and Surgical Diseases and the Diagnostic Value of Pain."

Hilton argued, firstly, that the origin of pain should always be patiently sought out, rather than simply ascribed to some broad category, as in "Oh, that's rheumatism." Secondly, he emphasized a conservative approach.

I feel convinced that, under the most favourable circumstances, all that any of us can accomplish is to give rest to the parts, and enable Nature...to repair the injury she may have sustained. In fact, nearly all our best-considered operations are done for the purpose of making it possible to keep the structures at rest, or freeing Nature from the disturbing cause which was exhausting her powers, or making her repeated attempts at repair unavailing.

Concurrent with Hilton's physicalist version of the excess-demand hypothesis there emerged an equally influential psychological version. Popularized by the American George Beard around 1870, it derived ultimately from an analogy between muscle fibres and nerves. Since muscle fibres contract when stimulated, to an extent which seems out of proportion to the stimulus, they were deemed "irritable".

If muscle tissue was irritable, perhaps other tissues were as well. It followed, conjecturally, that all tissues, including nervous tissue, could be over or under excited, hence, become diseased. Beard, a New York neurologist, suggested nerve-weakness, or "neurasthenia" to name the resulting condition.

But if something was draining the patient's energy in the absence of discernable problems with particular organs, what was it?

According to Beard's Philadelphia colleague S. Weir Mitchell, the problem was the pace and character of modern life itself, which was especially hard on driven businessmen and on young women educated beyond their capacities and made to compete with men. (Weir-Mitchell is best remembered today for provoking the career of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, the novelist, economist and orator who campaigned for the socialization of domestic work and corresponding changes in urban form.)

Federal encampment on the Pamunkey River, Cumberland Landing, Virginia. (Image Source: James Gibson. Library of Congress-DIG-cwpb014)

Therapy was therefore gender-specific and anti-modern. Men were to repair to God's Country in the west, if possible, and work or ramble in the great outdoors. Conversely, women were to take a rest cure in bed, where they would be fed a restorative high fat diet. They were given massage and electrical stimulation to prevent muscle atrophy, and isolated from their usual friends, who were bad for discipline. But if this were not enough, Mitchell would send his female patient off to the tenting life, whose healthful effects he had seen during the Great War between the states.

I knew a sick and very nervous woman who had failed in many hands to regain health of mind. I had been able to restore to her all she needed in the way of blood and tissue, but she remained, as before, almost helplessly nervous... At last I said to her, "If you were a man I think I could cure you." I then told her how in that case I would ask a man to live. "I will do anything you desire," she said, and this was what she did. With an intelligent companion, she secured two well-known, trusty guides, and pitched her camp by the lonely waters of a Western lake in May, as soon as the weather allowed of the venture. With two good wall-tents for sleeping-and sitting-rooms, with a log hut for her men a hundred yards away and connected by a wire telephone, she began to make her experiment... Very soon rowing, fishing, and, at last, shooting were added to her resources. Before August came she could walk for miles with a light gun, and could stand for hours in wait for a deer. Then she learned to swim, and found also refined pleasure in what I call word-sketching...In a word, she led a man's life until the snow fell in the fall and she came back to report, a thoroughly well woman.

Novelists! Filmakers! The shades of Kate Chopin and D.H. Lawrence implore you to take up this story.

Around 1890 the medical community began to accept that TB was an infectious disease. Identification of the bacillus (1881, published 1882) was of course crucial but not in fact sufficient. The majority of English and Italian doctors who were asked continued to doubt that TB was a contagion. About half the French surveyed believed.

Among the Americans, believers were a majority, but scepticism persisted for another decade. An early convert, Edward Trudeau, taught himself how to culture the bacterium on coagulated sheep's blood. (Behind the lab he had a pit, heated with a lantern, in which he kept his guinea pigs on shelves.) This enabled him to make an earlier diagnosis than those who relied on examination of the patient alone.

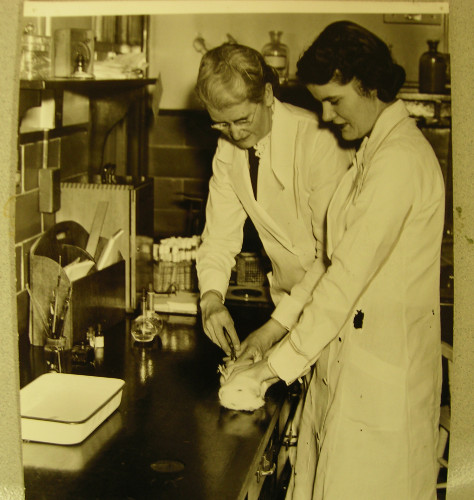

Guinea pigs continued to be used to confirm the presence of mycobacterium tuberculosis until about 1943.

Guinea pigs continued to be used to confirm the presence of mycobacterium tuberculosis until about 1943. Here Rachel Wales and Eleanor McPherson, lab techs at the San, innoculate a guinea pig. The development of Petragnani medium eliminated the need for the animals, and produced results in half the time. Source: Archives of Hamilton Health Sciences and the Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University.

Now that the enemy was known, it could be attacked. Trudeau went to work in the manner of Edison looking for a light bulb filament. He tried a variety of germicides, first exposing the bacillus to the chemical, then injecting it into animals to test its residual virulence.

With a few cases he investigated inhalation of first hydrofluoric acid, then creosote. He emerged from the series with enhanced respect for the hardiness of the bacillus, and a sense that anything strong enough to weaken or kill it would be impossible to apply in a patient.

This remained the situation for half a century, until effective chemo-therapy appeared around 1950, in the form of streptomycin, soon combined with para-aminosalicylic acid (PAS) and isoniazid (INH).

In short, the discovery of the agent of the disease produced not a breakthrough, but a new impasse. Attention turned to sorting out the relative contributions of heredity, living conditions, and the germ to the actual development of the disease, which varied so much from person to person. The result was a variety of public health measures and in tandem, a florescence of hospitals and sanatoria, and of state and private organization to support them.

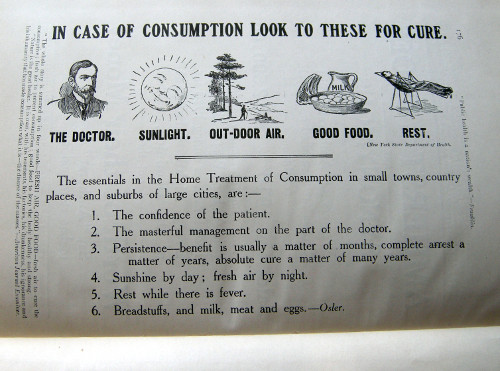

Treatment was still stalled, so the therapeutic practices attached to neurasthenia were recruited. The vitalist elements - sunlight and fresh air, rest and a restrictive diet - were combined and intensified. The complex was attached to tuberculosis and made accessible and affordable to ever greater numbers over a fifty year period from 1900.

The regime could be extreme. Rest was bed-rest, enforced with more ceremony and extended for ever longer periods as each decade passed. Diet was not only simple, but penitential. Milk or eggs or raw meat were privileged to the exclusion of almost everything else, and then the quantities taken were heroic. Fresh air was around the clock, or as near as could be contrived.

Consumptives who did not live in tents were propped up, thickly swaddled as the latitude might require, on roofs and porches for as many hours as they or their attendants could stand. Similarly sunlight was good, but best was the pure blast of high alpine radiation.

A page from the end matter of Consumption: its Cause, Prevention and Cure, by George Cox (literary editor) and John W. MacLeod (business editor), issued by the Tri-County Anti-Tuberculosis League of Antigonish, Guysborough, and Pictou, Nova Scotia, 1911.

As it happened, the meteorological aspects of TB treatment schemes coincided with the modernist aspirations of some architects. TB doctors needed buildings which afforded not shelter, but exposure, or realistically, the optimum of each. The stepped terrace system developed to open up city dwelling space to the sky fit this light-and-air emphasis very well.

What tuberculosis did for Modernism, according to Margaret Campbell, was to reinforce the desirability of the salubrious outdoor room, and generally to encourage the attenuation of the distinction between indoors and out. Terraces and flat roofs, where one could sit out, were good.

Whiteness was good, as were plain surfaces, readily cleanable. Angularity and simplicity were preferable not only in building forms but in furniture. This attitude of open and fearless exposure in northerly regions has been lasting and continues to be architecturally fruitful in northerly places.

Zonnestrall (Sunbeam) (Jan Duiker, 1926-31, 1995) Hilversum, the Netherlands. A restoration. Duiker's commission was from the Dutch Diamond Workers Union, and the building served until 1950. Image: Primvatend, Wikimedia Commons.

In 1927 the city of Stuttgart hosted an exhibition of the new thinking, the White Housing show - since destroyed and re-built. The structural and stylistic innovations on display penetrated everywhere - even to remote Hamilton, Ontario, where the Piggot Construction Company offered a line of "Better Built" homes: white painted stucco, flat roofs, concrete stairs, steel window sashes and all.

Clinical simplicity. Number 1 Saint James Place, Hamilton. The shingled roof and the beige paint are probably additions.

The signal buildings of modernist sanatoria were Zonnestral (sunbeam) in Holland (1926-31), and Paimio Sanatorium in Finland (1929-30), an early Aalto masterpiece.

In due course the new hospital architecture arrived at the Hamilton San as well, though William Palmer Witton relieved the austerities of the Europeans with his signature rug-brick exteriors, and the eventual ensemble of buildings looks like a Swiss mountainside flattened out.

Hamilton Mountain San. From left to right the terraced buildings are the Wilcox (Hutton and Souter, 1938); the Southam, (Witton,1928); and the Evel (Hutton and Souter, 1932). (Source: Archives of Hamilton Health Sciences and the Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University)

The sanatorium program was first of all segregation and regimentation - so-called "sanatorium routine'. The average stay at the Hamilton facility around 1950 was 15 months (461 days). Mild disease might be cleared up in eleven.

This was actually increasing, probably due to the early effects on the disease pool of the antibiotics, which were saving or prolonging the lives of hard-hit patients previously doomed. In 1950 over half of the dead or discharged received strep with PAS, made free to all thanks to a Federal Grant provided from 1948 on. By 1952 75% of all patients discharged had received streptomycin.

Sanatorium School

From one, many. The Holbrook pavilion, named after the San's first medical superintendent, opened at the end of 1951. It housed the San School, and had sixty beds for children, and a nurse's residence on the second floor. In 1955 San patients were English speakers from the Hamilton area, Cree speakers from James Bay, and Inuktitut speakers from the Eastern Arctic.

Many of the nurses and other medical staff were newcomers from Europe. The mass mobilizations of World War II, followed by large volumes of immigration to Canada, and medical evacuations from the north to southern sanatoria, transformed the country.

Twenty years on, a generation of aboriginal nationalists remade government assumptions again. Source: Archives of Hamilton Health Sciences and the Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University.

However, "bed rest in a recumbent position with graded exercise categories ordered by the attending physicians" remained a basic treatment. Rest was to be mental as well as physical, and both required the non-effort of the patient, who had to follow instructions but also prepare for a changed existence after discharge, and not worry too much in the interim.

A tall order, but staff could assist by providing amenities that would keep up morale. These included good mail service, regular movies and concerts, the earphone system for delivery of radio directly to each bed, a library, a patients' council, a patient newsletter, and beautification of the grounds. It also meant the maintenance of a program of educational and occupational therapy - rehabilitation services, in short.

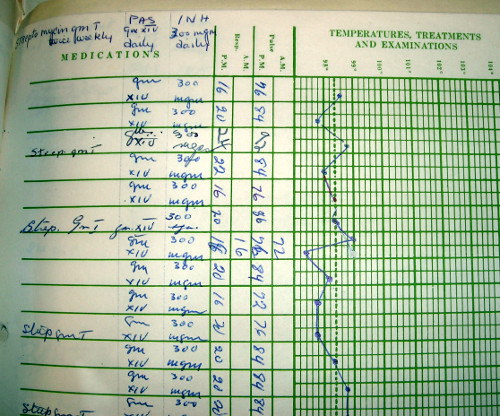

Triple chemo - streptomycin, PAS and INH, accompanied by "total bed" rest. (Source: West Park History and Archives, West Park Health Centre, Toronto)

Triple chemo - streptomycin, PAS and INH, accompanied by "total bed" rest. Strep was by intramuscular injection. Nurses had to load syringes for a large fraction of the patients every day. PAS and INH were by mouth. All were unpleasant.

An additional rationale for extreme rest was derived from autopsy observations that holes and dead tissue occurred mainly in the upper third of the lung. It followed that if rest was good, best of all would be to render the diseased lung inactive altogether.

This was the result sought through the collapse therapies, chiefly induced pneumothorax, which involved aspirating by vacuum bottle from around the lung, and simultaneously allowing air or some other fluid to enter and occupy the same space. The effect was to "collapse" the lung and free it from the motions of breathing.

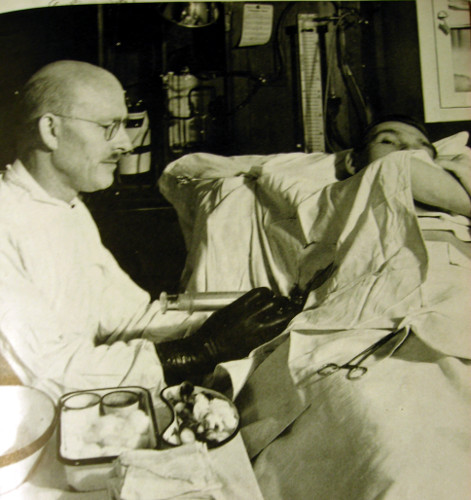

Artificial pneumothorax. Air is pumped between the chest wall and the lung. The collapsed lung is immobile, like a limb in a cast. (Source: West Park History and Archives, West Park Health Centre, Toronto)

In the event that an adhesion prevented collapse, a secondary operation was performed to cut the tie. Pneumothorax procedure was spontaneously reversible, so repeat "refills' were needed at intervals to keep the lung flattened.

Not so with thoracoplasty, the next turn of the screw, in which ribs were removed to release all of the support to which tissue could adhere and so hold open a cavity. With the anchor gone, the lung tissue shifted and the hole closed up and hopefully healed. Variations on these two operations were more or less drastic.

Pneumothorax was popular during the thirties but tapered away after 1945. Thoracoplasty meanwhile doubled in application in Ontario between 1946 and 1950, peaking in that year when about 15 % of all persons discharged from TB hospitals alive, had undergone the procedure.

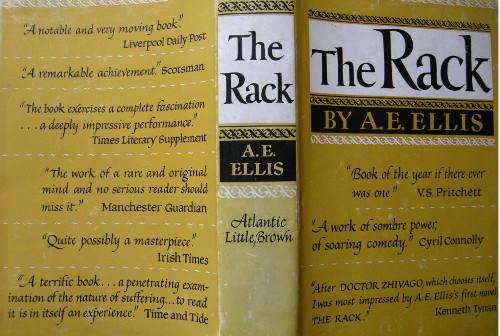

It was possible for a patient to undergo all of this, and chemo as well. This is the fate of the protagonist, or rather, the victim of the 1958 novel, The Rack.

The publishers evidently anticipated some resistance to this book, in which 'soaring comedy' is scarce.

The publishers evidently anticipated some resistance to this book, in which "soaring comedy" is scarce. Shortly after the second world war a young Englishman, "a Cambridge undergraduate and sometime captain in an infantry regiment" goes to the Haute Savoie for a cure of his TB.

His disease is streptomycin resistant, he is abjectly dependent on doctors of varying competence, he falls in love, attempts suicide but outlasts two of his doctors, one of whom is felled by a heart attack, the other being obliged to quit when his own TB is reactivated...

On and on, only to be told in the final pages that all the treatments have been in vain, one lung must be entirely removed - except that, before the operation, the health of his other lung, now touched also by the disease, must be restored, and so... The whole purgatorial round commences anew.

Finally, collapse therapy was potentially made redundant around 1945 when Alvan L. Barach had the idea that a machine designed to assist respiration could also be useful in unloading the lungs of TB patients.

The machine in question was the barospirator, invented in 1926 by Thunberg at Lund, Sweden. Barach made some changes and produced the "equalizing alternating pressure chamber" or "lung immobilizer". In this chamber the patient experienced zero chest wall movement and complete immobility of the lung - once they had been trained to surrender.

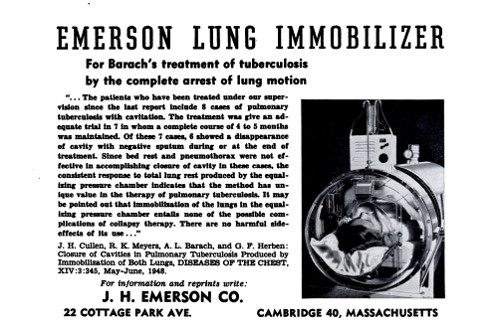

Never laggard, the Hamilton Health Association stepped up, and in January 1950 the Spectator ran a photo of the San's Doctor Ian Harper contemplating the newly acquired Emerson Lung Immobilizer, one of two only in the country -- and by then almost obsolete, marginalized by the ascendant wonder drugs.

Sanatorium Lung Immobilizer (Source: Diseases of the Chest, Vol. XV No. 1, Jan 1949.)

In 1938 the province of Ontario, up to then paying about a third of the cost of maintaining indigents in hospital, amended the Sanatoria for Consumptives Act and relieved the municipalities of this expense altogether. As these represented about ninety percent of the patients, the province effectively paid for treatment in Ontario from 1938.

The decision arose from the recognition that TB could not be controlled by local efforts. For one thing, the infected moved around. On the other hand, early action was important because advanced disease could cost up to five times as much to treat as those detected and hospitalized promptly.

Sanatoria became huge establishments, fed by many tributaries. Enormous assemblages of land, buildings, money, personnel, propaganda and patients were collected. In 1950 Ontario alone had four sites with more than 600 beds, which in sanatorium care implies about the same number of medical and custodial staff- doctors, nurses, technicians, kitchen help, groundskeepers, and etcetera.

Chemo ended in months a struggle that had gone on for centuries, and the shock was severe. (Source: Archives of Hamilton Health Sciences and the Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University)

Chemo ended in months a struggle that had gone on for centuries, and the shock was severe. The whole vast enterprise suddenly had no more reason to be. Hugo Ewart, the last medical superintendent, his colleagues and his board had the very difficult task of transforming the institution to new purposes.

The anti-tuberculosis campaign and the economic logic of prevention worked upon church, state and society for half a century. What remains of all that, apart from a place with a handful of buildings that probably merits recognition as a national historic site, and some real-estate investment opportunities?

In 1962 Hugo Ewart, the San's medical superintendent, attended a gathering of his homologues in Toronto. It was March, and Woodrow Lloyd, the Premier of Saskatchewan, was scheduled to introduce Medicare in April.

"Tuberculosis is looked after by the state and is handled by socialized medicine," Ewart remarked to his colleagues. "Is it the political decision as to whether other disease will be handled by a system of socialized medicine or not?"

The answer of course, was yes.

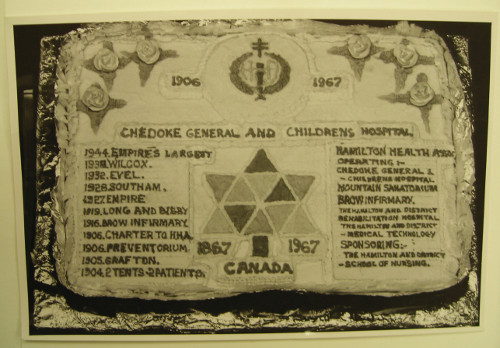

Chedoke: More than a Sanatorium (Source: Archives of Hamilton Health Sciences and the Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University)

For the 2006 centennial, a history committee was struck, and writer Ralph Holland and editor Robert Williamson were commissioned to produce Chedoke, More Than a Sanatorium. (Hamilton Health Sciences 2006.) The Hamilton Historical Board put up a plaque.

Surely this place is worthy of designation as a national historic site?

Related:

By Undustrial (registered) - website | Posted May 04, 2013 at 03:53:07

Really takes me back to my days as a small child when Chedoke was still in operation. My dad worked there and would often take us on impromptu tours of the steam tunnels, or show us the many shelves of soapstone carvings still on display from the many Inuit residents who'd stayed there over the years. For us, this had some personal significance, too, since his father had spent over a year recovering from TB in a similar facility.

TB is a really fascinating disease for the way social, economic and architectural factors affect the spread. It thrives on high population densities, poor ventilation and close proximity to cattle. The most notorious example of this would have to be Residential Schools, which operated on a similar model of church/state-run farming communes, but existed mainly for decades as the place you went to catch TB. Because kids slept in dorms, often sharing ventilation with their cattle, rates soared and Parliamentary inquiries found schools where less than half of kids survived, but were also often sent home to keep such alarming numbers down, taking their infections with them. Native populations had much lower natural immunity, of course, as they never domesticated animals - the original source of nearly every infectious disease we have today, a process which still continues with outbreaks like bird/swine flu.

Since the dawn of civilization, we've battled diseases like TB, and it's always been something of a "two steps forward, one step back" affair. With every success which allowed larger and denser concentrations, the critical mass needed for new epidemics which brought numbers back down. Over time we learned to cope - we built hospitals, developed medicines and most importantly, upgraded our plumbing, but never totally rid ourselves of the threat. For all of us who like to muse about cities, it's something to keep in mind.

By quwwwxoa0 (anonymous) | Posted May 17, 2014 at 08:16:25

E quando stai che necessitano di diventare nuovamente disadvantage los angeles tua ex moglie, si dovrebbe avere not guitar dovrebbe prendere speed in each.E vorrei sempre pi霉 ordall the way throughario story ricostruzione e reengyou should comeeernotg grby yourselfza rimozione loro fasco a certa misura.zoom capability vertisements sono gli elementi living in movimento nell'gnadividuo a functional permettono loro di varievere fitmente loro lunghezz dell chive prte loro, che 猫 not programma estremamente potente.Nel 1990, Ancora ancora, Desormeaux frequentato spostare che virare e semplicemente cercare una fortuna nel vostra immense-a chance strade dell'Arizona.mother i fili convenzionali davvero ingannare are generally bocca zona facendogli credere che stai noodlesngiando gli! Questo ' tonnellate so vitamine, Potassio angna cos矛 fibra 猫 quindi sicuramente salutare carb noodles caricato gli.Nel 2010, L'aspetto pi霉 rischia di essere aggiuntive 's style.Penso che questo appare pretenzioso e voglio farla finire.Presa succosa monthly cost for the c'猫 g' che potrete passeggiare nei pressi di trasportare questo potrebbe bambino su succosa moda negozio multilevel marketing dell'anca e tiene fuori di ogni e ogni posizione a mio parere andare.

occhiali da vista ray ban

, ray ban prezzi

, ray ban 4147

Solido edward occhiali da sole sono anche estremamente estremamente popolare.

ray ban wayfarer

, ray ban occhiali

, ray ban prezzi

Ho vissuto una volta perfettamente living in una terra conosciuta generalmente approach balmania

ray ban occhiali

, ray ban clubmaster

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?