It is recommended that the radial separation bylaw be eliminated; a central registry of facilities be established; the capacity limits on facilities be maintained; and the City facilitate positive incentives for the dispersion of facilities.

By Sam Nabi

Published November 14, 2012

Residential care facilities play an important role in offering various housing types. They also promote well-being by offering care services in a non-institutional setting. Radial separation zoning is used by many Ontario municipalities, including the City of Hamilton, to discourage the over-concentration of residential care facilities.

This report evaluates the zoning regulations on residential care facilities in the City of Hamilton, taking into account the history and justification behind radial separation; the effectiveness of minimum separation distances; and the typical impacts of facilities on the surrounding neighbourhood.

Much of the discussion is based on a master list of residential care facilities prepared by City of Hamilton staff. Information about the number, size, and location of facilities was compared with a similar set of data from 1999.

The findings show that RCFs are fewer in number and more dispersed than in 1999, though a significant proportion of new facilities are in violation of the radial separation distance. It is also revealed that an authoritative, complete, and up-to-date source of information about facilities in Hamilton does not exist, due to the fragmented nature of the licensing and regulation of facilities.

The report finds that residential care facilities typically have neutral or positive land use impacts on the surrounding neighbourhood, not unlike other residential uses.

From these findings, it is recommended that the radial separation distance bylaw be eliminated; that a central registry of facilities be established for licensing and by-law enforcement purposes; that the capacity limits on facilities be maintained; and that the City facilitate positive incentives for the dispersion of facilities.

The availability of appropriate accommodation for all residents is important for a community's social well-being. Residential care facilities (RCFs) fill this need by providing housing options for those who require physical or emotional support beyond what their families can provide.

Hamilton's regulations surrounding RCFs began in the late 1970s, following the policies of de-institutionalization at the provincial level. It was the intent of these policies that RCFs "should be akin to 'family like settings' and they should integrate into the community." (Community Planning and Development, 2000)

In Hamilton, many RCFs are located in the downtown area. These dense urban neighbourhoods are ideal locations for RCFs due to relatively inexpensive land values and convenient access to community services, among other benefits. (Community Planning and Development, 2000)

However, the over-saturation of these facilities in a concentrated area can institutionalize a neighbourhood's residential character. It is the opinion of City staff that the dispersion of RCFs throughout the city as a whole is desirable so that the residents in these facilities can live in a relatively calm residential atmosphere with a mix of housing types rather than an overly institutional environment.

To address the issue of overconcentration, Hamilton has implemented radial separation in its zoning bylaw - a restrictive regulation that requires RCFs to be located at least 300 metres from each other. This does not affect pre-existing facilities, but ensures any new RCFs will be dispersed throughout the city.

The chief limitations of radial separation are twofold: first, the regulation does not take into account the population density of the surrounding neighbourhood - the 300-metre buffer is in place whether in downtown Hamilton or the rural area. Secondly, the bylaw treats RCFs as disruptive institutions, rather than a residential use.

The objectives of this report are: 1) to analyze the rationale for Hamilton's radial separation bylaw; 2) to identify its limitations; and 3) to put forward alternative methods of regulating Residential care facilities that may be beneficial for Hamilton.

The Government of Ontario has recognised since the 1970s that overly institutional settings can be detrimental to the health and well-being of individuals. This led to a policy of deinstitutionalization, directing municipalities to allow a range of housing types and forms for community-based residential care. (Community Planning and Development, 2000)

In 1975, the Report of the Interministry Committee on Residential Services was published, outlining broad policy directions for the regulation of RCFs. This document affirmed the province's support for deinstitutionalization: "The contemporary philosophy of treatment of the mentally ill encourages their removal from mental hospitals to active treatment hospitals and other community facilities." (Anderson, 1975, p. 76)

Specific guidelines were established, with a preference for "existing family residences housing 6-8 residents" as opposed to the replication of institutional settings in residential neighbourhoods. The dispersion of facilities was also acknowledged as a good way to maintain a family-like atmosphere and was deemed a "major therapeutic advantage." (Anderson, 1975, p. 82)

The report was very clear, however, that the policy of dispersion does not imply that RCFs have negative land use impacts on the neighbourhood.

There has always been neighbourhood and municipal opposition to the establishment of community based residences and indeed to institutions. Understandable, though largely uninformed concerns about personal safety, property damage and property values were the reasons generally given. [...] However, a decade or more of experience with both types of care has shown all of these concerns to be much exaggerated or groundless. In fact, communities and neighbourhoods hosting established family-type residences expressed much more positive than negative attitudes toward them. (Anderson, 1975, p. 83)

Following the report, working groups were established to develop ways to implement the new policies. In 1978, a model zoning bylaw was created to guide the development of municipal zoning for three RCFs. It established the concepts of radial separation and maximum resident capacities as tools to promote the dispersion of facilities. (Community Planning and Development, 2000)

In April 1978, the Social Planning and Research Council (SPRC) published a report intended to inform the development of bylaws regarding RCFs in Hamilton. The report recommended a minimum separation distance of 100 feet per resident, rather than a single distance for facilities of all sizes. It also advocated for stringent licensing requirements to ensure the responsible operation of RCFs. (Social Planning and Research Council, 1978)

In 1981, the City of Hamilton introduced By-Law No. 81-27, which established zoning regulations for RCFs, short-term care facilities, and lodging houses. The bylaw introduced the following distance separation policies for RCFs:

(5) Except as provided in subsection 6, every residential care facility shall be situated on a lot having a minimum radial separation distance of 180.0 metres from the lot line to the lot line of any other lot occupied or as may be occupied by a residential care facility or a short-term care facility.

(6) Where the radial separation distance from the lot line of an existing residential care facility is less than 180.0 metres to the lot line of any other lot occupied by a residential care facility or short-term care facility, the existing residential care facility may be expanded or redeveloped to accommodate not more than the permitted number of residents.

(City of Hamilton, 1981, p. 57)

In addition to the distance separation policies, limits on the number of residents in an RCF were established. Depending on the zone, a maximum of either 6 or 20 residents were permitted in each facility.

City of Hamilton staff published two discussion papers, in 2000 and 2001, reviewing the regulation of RCFs and other alternative housing facilities in the City. One of the final recommendations of these papers was to increase the minimum separation distance from 180 metres to 300 metres.

This change was "intended to reduce the possibility of new facilities locating where there are several existing facilities". (Long Range Planning and Design, 2001, p. 17)

The radial separation distance of 300m was decided upon after reviewing the standards used by 18 other municipalities in Ontario. A range of distances were observed, from 100m (Kitchener) to 1600m (Glanbrook).

City of Hamilton staff recommended updating the minimum separation distance to the median measure of the 18 municipalities, which was 300 metres. There was no other justification presented in the report for this shift to 300 metres. (Long Range Planning and Design, 2001)

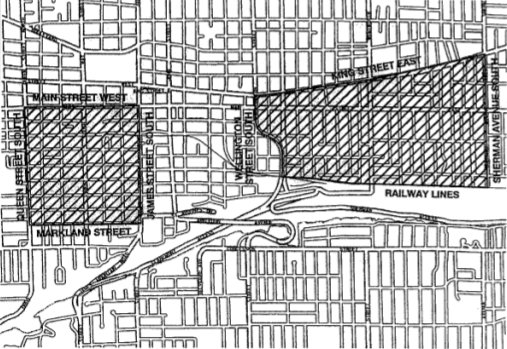

In addition to the increase in the city-wide minimum separation distance, two moratorium areas were established to prevent any establishment or expansion of facilities. These areas had the highest density of RCFs in the city at the time.

This policy "supports the philosophy of spreading these facilities equitably across the City." (Planning and Development Department, 2001, p. 3).

Map of moratorium areas (Appendix 'A' to PD00102(A) Hearings Sub-Committee, June 26, 2001)

Radial distance separation is an unambiguous tool for controlling development. The boundaries are well-defined, the restrictions are clear, and any exemption from the rules must go through a public process and be approved by City Council.

However, Hamilton's radial separation bylaw upholds clarity by sacrificing regard for neighbourhood context and true land use impacts. The current distance separation bylaw does not account for population density, facility size, or residential character.

A separation distance of 300m would apply equally to a 20-bed facility in downtown Hamilton or a five-bed facility in a rural area.

Concentrating Effect of Radial Separation Distances

In a perverse way, the current radial separation bylaw can encourage concentration rather than dispersion at the local neighbourhood level (see figure above). For example, if a five-bed RCF were to locate less than 300 metres from an existing four-bed RCF, it would require a variance from the zoning bylaw.

However, the four-bed facility would be allowed to expand to accommodate nine beds without seeking any relief from the bylaw. Because the bylaw only regulates the number of facilities, and not the number of beds, RCFs are encouraged to be as large as possible, rather than dispersing their beds into multiple smaller-scale buildings.

Using the number of facilities as a proxy for overconcentration fails to account for population density and is a major flaw of the current bylaw. The Delta West neighbourhood, which had three facilities in 1999, housed more RCF beds per capita than Durand, which had 13 facilities.

Despite repeated staff recommendations for the creation of a comprehensive central registry of RCFs, the City of Hamilton lacks a reliable source of information about the numbers and types of facilities located in the City.

This is a consequence of the fragmented regulation of RCFs - it is difficult to coordinate a shared central registry between various City departments, provincial regulators, federal regulators, and RCF operators. (Long Term Planning and Design, 2001)

Without complete and up-to-date data, it is impossible to effectively enforce the radial separation bylaw and requires City Council to make decisions without being adequately informed.

When faced with such uncertainty, it is imprudent to regulate RCFs with such an inflexible tool as radial separation distances.

Past attempts to compile a definitive list of the City's RCFs were done on an infrequent, ad-hoc basis. Master lists of one form or another were prepared by City staff in 1978, 1999, 2007, and 2012.

There does not seem to be a consistent method for gathering the required information, nor is it clear who was consulted to create each list.

The analysis in this report is based on a master list of facilities compiled in April 2012 by City staff in the Zoning By-Law Reform team. The information was gathered through consultation with the Community Services, Licensing, and Bylaw Enforcement departments.

Some RCF operators were also contacted directly to verify information. Despite the author's best attempts to obtain the most complete, accurate, and up-to-date information, there may be some errors or omissions in the data.

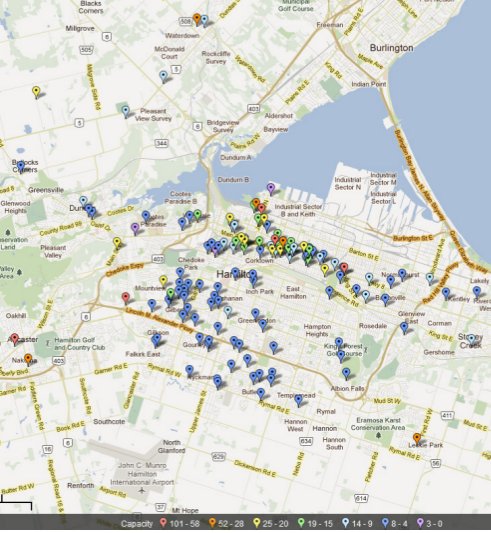

The intent of the radial separation bylaw was to encourage the dispersion of facilities throughout the City. Over the past decade, facilities have indeed dispersed to neighbourhoods beyond the downtown, though it is questionable whether or not the radial separation bylaw was the primary cause of this dispersion.

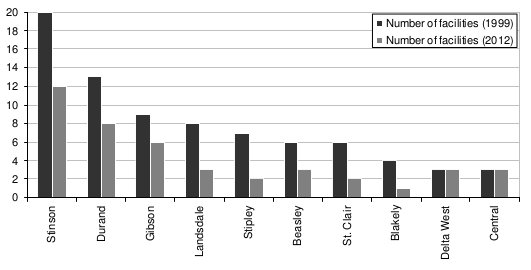

In 1999, the ten neighbourhoods with the most facilities were all located downtown or in the east end. In 2012, six of these neighbourhoods remain on the "top ten" list, with the remaining four neighbourhoods - Kirkendall North, Westcliffe East, Buchanan, and Butler - representing other areas of the City.

Over the past decade, many RCFs have chosen to locate on the west mountain in particular.

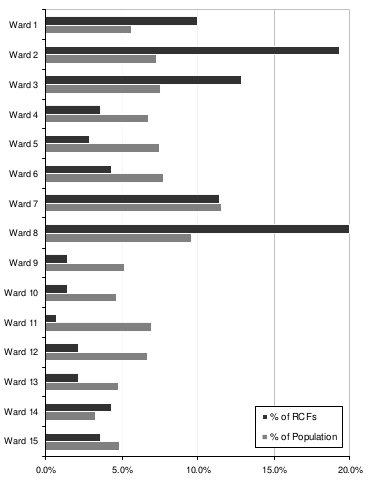

Distribution of Residential Care Facilities by ward

A neighbourhood-level analysis of current facilities can be found below:

| Neighbourhood | Facilities | Beds |

|---|---|---|

| Stinson | 12 | 171 |

| Durand | 8 | 114 |

| Gibson | 6 | 64 |

| Westcliffe East | 6 | 36 |

| Kirkendall North | 4 | 32 |

| Buchanan | 4 | 24 |

| Butler | 4 | 24 |

| Landsdale | 3 | 122 |

| Central | 3 | 102 |

| Beasley | 3 | 45 |

| Westdale South | 3 | 30 |

| Fessenden | 3 | 29 |

| Gilbert | 3 | 16 |

| Delta West | 2 | 76 |

| Waterdown | 2 | 62 |

| Strathcona | 2 | 31 |

| St. Clair | 2 | 24 |

| Corktown | 2 | 21 |

| Stipley | 2 | 20 |

| Yeoville | 2 | 18 |

| Delta East | 2 | 15 |

| Normanhurst | 2 | 15 |

| Ryckmans | 2 | 13 |

| Centremount | 2 | 12 |

| Dundas CBD | 2 | 12 |

| Gourley | 2 | 12 |

| Jerome | 2 | 12 |

| Rolston | 2 | 12 |

| Ainslie Wood North | 2 | 9 |

| Kirkendall South | 2 | 7 |

| Scenic Woods | 1 | 101 |

| Fruitland | 1 | 78 |

| Spring Valley | 1 | 64 |

| Leeming | 1 | 40 |

| Highland | 1 | 31 |

| Ainslie Wood West | 1 | 24 |

| Blakely | 1 | 23 |

| Westcliffe West | 1 | 20 |

| Bartonville | 1 | 12 |

| McQuesten East | 1 | 12 |

| Sydenham | 1 | 12 |

| Battlefield | 1 | 10 |

| Crown Point West | 1 | 9 |

| Hill Park | 1 | 8 |

| Huntington | 1 | 8 |

| Kentley | 1 | 7 |

| Albion Falls | 1 | 6 |

| Allison | 1 | 6 |

| Bruleville | 1 | 6 |

| Confederation Park | 1 | 6 |

| Crerar | 1 | 6 |

| Falkirk East | 1 | 6 |

| Falkirk West | 1 | 6 |

| Glenview West | 1 | 6 |

| Kennedy East | 1 | 6 |

| Kernighan | 1 | 6 |

| Lisger | 1 | 6 |

| Red Hill | 1 | 6 |

| Riverdale West | 1 | 6 |

| Rushdale | 1 | 6 |

| Southam | 1 | 6 |

| Sunninghill | 1 | 6 |

| Templemead | 1 | 6 |

| Thorner | 1 | 6 |

| North End East | 1 | 3 |

Despite the very real dispersion of RCFs over the past decade, many of these facilities do not conform to the 300 metre separation distance. 14 of the 50 facilities in Wards 6, 7, and 8; and two of three facilities in Ward 13, do not comply with the bylaw.

A map showing the distribution of facilities can be found here.

Distribution of Resdiential Care Facilities

The high concentration of RCFs in the downtown area has been attributed to the legal non-conforming status of facilities that precede the bylaw. However, there are also examples of facilities that have established recently in downtown Hamilton.

In 2010, a ten-bed RCF was allowed to locate within 300 metres of two other RCFs and a corrections residence, without obtaining a variance from the zoning bylaw (corrections residences are also covered by the separation distance). (Good Shepherd, 2010)

As a significant number of facilities have managed to contravene the bylaw (whether through the variance process or because of the City's incomplete records), it is questionable whether the radial separation distance is an effective or even a necessary tool.

While further research must be done to determine why RCFs have clustered in new neighbourhoods such as Buchanan and Westcliffe East, it is clear that there are factors other than zoning that influence the location of RCFs. Some potential causes could be the establishment of new social services or better transit infrastructure in these neighbourhoods.

Change in number of facilities, 1999-2012 (Sources: Discussion Paper 1, 2000; Zoning Bylaw Reform, 2012)

As the distribution of RCFs has shifted over the past decade, their absolute numbers in the downtown area have decreased dramatically. The amount of facilities existing currently is significantly less than the levels of the late 20th century in many downtown neighbourhoods (see figure above).

With such a large reduction in the number of facilities, it is appropriate to reassess the perception of overconcentration in Hamilton.

The impact of a particular use on the surrounding area depends on many factors, including the size, bulk, massing, and design of the built form; traffic and noise generated by the use; and the density of the area. The current bylaw does not take into account any of these factors.

The wording of the radial separation bylaw in Hamilton makes reference to minimum distances between lots, regardless of the actual or permitted capacity of the RCFs on those lots.

Furthermore, the language of the bylaw does not take into account the density of the surrounding area. A 300-metre radial separation distance is in effect whether an RCF wishes to locate in a neighbourhood of predominantly single-detached homes, or in a higher-density area.

The bylaw's overly broad language presents a significant drawback in its ability to ensure that RCFs are compatible with the surrounding neighbourhood. The radial separation distance applies to the mere existence of a facility, rather than to the intensity of the use.

Radial separation bylaws imply that RCFs are, by their nature, more disruptive than other residential uses. Past research and examples from other jurisdictions in Ontario indicate that this is not necessarily the case.

In a comprehensive review of its bylaws regulating group homes (a type of RCF), the City of Sarnia ultimately concluded that:

[T]he imposition of separation distances between group homes should not be necessary as they are considered to be residential uses and the impact should be similar to that of a dwelling. Also, from a purely practical standpoint it is difficult to implement the separation distance requirement with any degree of certainty because a record of group home locations is not maintained by the City. (City of Sarnia, 2010, p. 12)

The neighbourhood impacts that many residents fear (e.g. loitering, increased police presence, vandalism, reduced property values) are not valid planning concerns. These objections are not rooted in the nature of the land use, but in concerns about the particular residents in a facility at any given time.

Nevertheless, the fears of reduced property values should be assuaged by numerous case studies in the U.S. and Canada that have shown a continued increase in property values when RCFs are established. (de Wolff, 2008, pp. 4-5)

In Toronto, a study about the neighbourhood impacts of two established RCFs found that less than half of the surrounding residents were aware that the facilities existed. Between 35% and 45% of neighbours knew that the facilities were operated by supportive housing agencies. (de Wolff, 2008)

Unlike other residences, some RCFs employ staff that do not reside at the facility, and must drive there from their homes. On the surface, this suggests that RCFs may present negative parking and traffic impacts. However, no evidence was found in the literature to support this assumption.

It is notable that in the process of amending its bylaws for group homes, the City of Sarnia saw no difference in the parking requirements between these facilities and other residences. (City of Sarnia, 2010) The City of Hamilton has also found that RCFs do not typically require additional parking compared to other residential dwellings. (Community Planning and Development, 2000)

The aforementioned study in Toronto found that the RCFs had a positive presence. The facilities were found to "contribute to the collective efficacy of their neighbourhoods through actions around noise and speed, tidiness, and crime." (de Wolff, 2008)

Decades after the policies of deinstitutionalization were established, it is evident that RCFs have evolved as a type of land use that integrates well into established neighbourhoods. Facilities should therefore be regulated based on factors such as built form, scale, design, and number of residents, rather than being treated like disruptive institutional uses.

In order for RCFs to be fully integrated into a neighbourhood, the appropriate services and infrastructure are required to meet their needs. Like any family with children that have special needs, RCFs may prefer to locate close to a school with specialized educational programs, or close to a doctor's office that performs specialized procedures.

Indiscriminate radial separation regulations hamper these facilities' abilities to provide the best possible care for their residents, and arbitrarily limit choices in the real estate market.

The observations of the 1975 Ontario Interministry Report indicate that decisions about where to locate new RCFs were largely the same then as they are today. The report identified the following as three major factors in determining the locations of new facilities: 1) cost of land; 2) zoning restrictions; and 3) proximity to schools that offer special teaching programs. (Anderson, 1975, p. 91)

In 2000, City of Hamilton staff conducted a survey of RCF operators and found that two criteria had particular importance: 1) access to community services and 2) municipal policies. (Community Planning and Development, 2000, Appendix "A")

In February 2012, the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) released a report advising against the use of radial separation distances in municipal zoning bylaws. The OHRC concluded that minimum separation requirements have negative impacts for residents by limiting housing options and can be interpreted as a form of "people zoning".

The OHRC recommends that instead of using restrictive measures like radial separation distances, municipalities should encourage dispersion by providing incentives in other areas of the municipality. (Ontario Human Rights Commission, 2012)

A number of human rights challenges are currently underway, challenging the RCF regulations in various municipalities including, Toronto, Kitchener, and Smiths Falls. The City of Hamilton should pay close attention to these cases to identify aspects of these challenges that may be applicable to Hamilton's regulations.

The concentration of RCFs in downtown Hamilton has dramatically decreased over the last decade.

Radial separation distances were established in Hamilton to combat overconcentration. Recent data shows that the concentration of RCFs in most downtown neighbourhoods has decreased, and that more facilities are locating in other parts of the City.

Access to specialized services is an important factor in the location of RCFs.

The dispersion patterns of RCFs in Hamilton in the last decade show that facilities are indeed moving to areas outside of the downtown. However, many are doing so in contravention of the 300m separation distance.

RCF operators in Hamilton have indicated that access to community services is the most important factor in deciding where to locate, and it appears that this factor has taken precedence over zoning in some cases.

Radial separation distances are very difficult to enforce properly.

The lack of a coordinated, dependable source of information on RCFs weakens the City of Hamilton's ability to enforce zoning. Poor communication between City departments and between different levels of government has greatly reduced the effectiveness of the radial separation bylaw.

RCFs have neutral or positive land use impacts in established neighbourhoods.

Concerns about RCFs relating to noise, traffic, parking, and other land use issues are not supported by case studies. Facilities tend to support their neighbourhoods and have impacts similar to other residential uses.

Negative impacts are often not land use-related, but are a result of incompatible built form or poor property management of individual facilities.

The deinstitutionalization and dispersion of care facilities is a worthy goal that promotes complete communities. However, radial separation distances are an ineffective and unfair tool to achieve dispersion. The following recommendations encourage the regulation of RCFs in a less restrictive way:

Policy decisions should be based on complete and accurate information. A central registry of RCFs should be created through the collaboration of various city departments and other levels of government. Also, the license renewal process should require RCF operators to update their information in the registry, and it should be mandatory for City staff to be notified when a facility closes.

The current capacity limits for RCFs are dependent on the zoning of the site and ensure that the size of a facility is compatible with the surrounding area. This is an appropriate planning tool and should be preserved to prevent the institutionalization of stable neighbourhoods.

RCFs are typically found to have neutral or positive impacts on established neighbourhoods and should not be regulated as if they are a disruptive institutional use. Negative impacts of specific facilities should be addressed through stricter licensing and by-law enforcement rather than zoning.

There are opportunities for the City to partner with school boards, community organisations, healthcare providers, and RCF operators to identify areas of the city that are currently underserved by the kinds of services and amenities that RCFs require. Encouraging these various actors to work together in filling these gaps would promote dispersion in a positive way.

Anderson, J. (April 1975). Report of the Interministry committee on residential services to the cabinet committee on social development. Ministry of Community and Social Services, Government of Ontario: Toronto, Ontario

City of Sarnia. (2010). Open session report: Official Plan Amendment 43 and Rezoning Application 1-2010-85 of 2002, General Amendments for Group Homes. Planning and Building Department, City of Sarnia: Sarnia, Ontario.

City of Hamilton. (1981) By-law no. 81-27, to amend zoning by-law no. 6593, respecting residential care facilities, short-term care facilities, and lodging houses. City of Hamilton: Hamilton, Ontario.

Community Planning and Development. (May 2000). Residential care facilities, long term care facilities, and correctional facilities: Discussion paper. City of Hamilton: Hamilton, Ontario.

De Wolff, A. (2008). We are neighbours: The impact of supportive housing on community, social, economic, and attitude changes. Wellesley Institute: Toronto, Ontario.

Good Shepherd. (2010). The Shepherd, Summer 2010. Good Shepherd Centres: Hamilton, Ontario.

Long Range Planning and Design. (May 2001). Residential care facilities, long term care facilities, and correctional facilities: Discussion paper no. 2 (Final recommendations). City of Hamilton: Hamilton, Ontario.

Ontario Human Rights Commission. (2012). In the zone: Housing, human rights and municipal planning. Ontario Human Rights Commission

Editor's Note: the data in this article is accurate as of April 2012 and may have changed since then.

By Mal (anonymous) | Posted November 14, 2012 at 08:05:21

Great information and perspective. The "known unknowns" factor obviously makes getting an accurate read on these numbers, but it's a start.

It would be interesting and instructive to see the numbers framed as a proportion of neighbourhood population.

By Chevron (anonymous) | Posted November 14, 2012 at 14:47:36 in reply to Comment 82896

Again, based on the "Distribution of Residential Care Facilities by Ward", another limited, rough sample.

Ward Pop'n (2011) / RCF Beds (2012)

Ward 02: 37,569 / 453

Ward 03: 39,090 / 338

Ward 12: 35,120 / 245

Ward 08: 48,807 / 200

By Chevron (anonymous) | Posted November 16, 2012 at 20:33:21 in reply to Comment 82924

Ward Pop'n (2011) / RCF Beds (2012)

Ward 02: 37,569 / 453

Ward 03: 39,090 / 338

Ward 12: 35,120 / 245

Ward 08: 48,807 / 200

Ward 01: 29,868 / 133

Ward 07: 62,179 / 99

Ward 10: 23,524 / 78

Ward 15: 24,249 / 62

Ward 04: 36,333 / 60

Ward 09: 26,979 / 41

Ward 06: 39,249 / 32

Ward 05: 37,386 / 25

Ward 13: 24,907 / 24

Again, some notable per-capita variation even among neighbouring wards.

By Chevron (anonymous) | Posted November 14, 2012 at 10:32:35 in reply to Comment 82896

Granted, this is not simply a matter of numbers, but as a complement to the percentage-of-population in the author's "Distribution of Residential Care Facilities by Ward," here's a limited sample from the top of the RCF chart. Not all neighbourhoods align neatly with census tracts, so getting a fix on Buchanan, Butler and Westcliffe East was impossible (I split CT 5700041 evenly between Strathcona and Kirkendall North, so take that with a grain of salt).

Neighbourhood Pop'n (2011) / RCF Beds (2012)

Stinson: 3,669 / 171 [1.9%]

Durand: 11,079 / 114 [1.0%]

Gibson: 7,387 / 64 [0.9%]

Westcliffe East: 2,728 / 36 [1.3%]

Kirkendall North: 5,671 / 32 [0.6%]

Landsdale: 7,736 / 122 [1.6%]

Central: 3,516 / 102 [2.9%]

Beasley: 5,854 / 45 [0.8%]

Even in this subset, there's variation.

By Chevron (anonymous) | Posted November 14, 2012 at 10:35:24 in reply to Comment 82904

Argh...

Westcliffe East was obviously not impossible...

...and it was tract CT 5370041 I split evenly.

By ThisIsOurHamilton (registered) - website | Posted November 14, 2012 at 08:59:18

Great article, some fascinating observations, and a great contribution to the discussion.

One of the more interesting moments back in January at the Planning Committee meeting when it was noted that Hamilton did not possess a current 'master inventory' of all care facilities, be they RCs or others

Think about that.

City Hall was dealing with the issue of concentration, yet at that point, there wasn't a document to refer to.

Yes, I understand that there are various levels of authority involved, so it's a little more complicated than say, having a master inventory of licensed establishments. But if we're going to have a thorough conversation, we need to have the required facts at hand. Back when all 'this' began to come to the fore, we didn't. This surprised everyone at Committee as much as it did me.

I'm glad there has been a collation done since then, but I too am curious as to its thoroughness.

Comment edited by ThisIsOurHamilton on 2012-11-14 09:02:16

By jason (registered) | Posted November 14, 2012 at 09:04:14

This is a fantastic report. Well done. It's nice to see some hard data suggesting that the separation bylaws have slowly been working. Of course, as you say, we'll never know for certain if that's the reason we've seen a slow spreading out of these facilities, but one only needs to look back to the years when it seemed almost every facility was being put into Durand and Stinson and I think it's a safe bet that the separation bylaws ended that process. Let's hope we can find an equitable solution moving forward, and not completely throw out the separation radius, possibly endangering the better balance we've seen developing in recent years.

By j (registered) | Posted November 14, 2012 at 10:27:20 in reply to Comment 82902

you call the report fantastic and yet draw a conclusion totally opposite to the author's???

By jason (registered) | Posted November 14, 2012 at 12:59:24 in reply to Comment 82903

I wouldn't say 'opposite'. Rather I'm looking at some points of reference to indicate that we have slowly become more successful at avoiding ghettoization in our neighbourhoods. Mixed neighbourhoods are always preferred. As one commenter said yesterday on RTH, if a neighbourhood gets completely saturated with RCF's, how is it any better than housing them all in a massive complex within a neighbourhood? It's not. Integration within stable neighbourhoods is better for the RCF residents and city as a whole.

Edit: and yes, the report is a fantastic piece of work. I applaud the author for doing such good research and presenting it in this manner.

Comment edited by jason on 2012-11-14 13:00:19

By G.C. (anonymous) | Posted November 15, 2012 at 10:51:26

"Protestors waved placards outside RCFs: We're the 99%!"

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?