Any growth of world oil demand at even 1.5% a year for more than three or four years is impossible to satisfy, because this would create a permanent Peak Oil context.

By Andrew McKillop

Published May 03, 2012

Peak Oil can be defined at least four ways, but one way is simple: Peak Oil is when supplies and stocks are tight enough, relative to demand, to make price slides short and price hikes long. This will continue until and unless the economy tilts into recession through market forces, or by policy decision in response to either external or internal shocks.

Examples of the second feature the post-2008 bank, finance and insurance sector crisis, and the sovereign debt crisis of many OECD countries since 2008.

The most recent example of 'runaway' oil price hikes was in 2007-2008, culminating in US Nymex oil prices at around $145 a barrel, with little or no difference between Brent and WTI prices. Only the entry to recession, from mid-2008 and through 2009, cut prices.

Today, in May 2012, the oil importer countries of the OECD group, according to their energy watchdog agency the IEA, are consuming about 46.25 million barrels per day (Mbd), still 1.25 Mbd below the five-year average for oil consumption by the 30-nation developed economy group, and about 1.33 Mbd below their early 2008 demand peak - which coincided with the most recent peak price.

The percentage share of this 1.33 Mbd cut in oil demand due to recession, compared with all other causes (energy and oil saving, development of renewable energy) is very high, and can be set at a minimum of three-quarters of this temporary fall in demand.

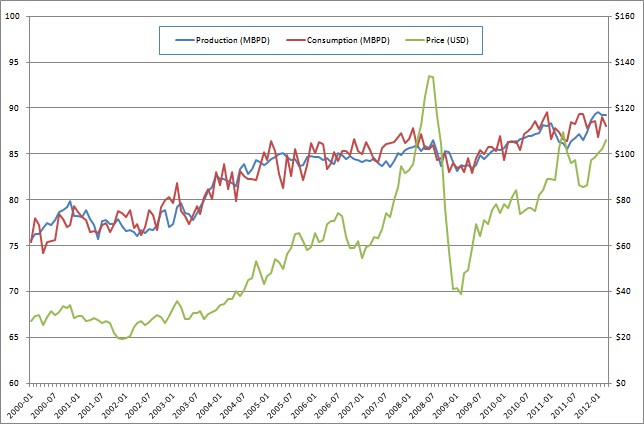

Global monthly oil production, consumption and price, 2000-2012 (Data source: EIA)

Taking the OECD group's total population of about 1.10 billion, this oil consumption rate is an average of around 15.3 barrels per capita per year (bcy) on a 2012 basis. At the same rate of oil demand, China would consume 54.6 Mbd (real consumption in early 2012 is 9.3 Mbd) and India would consume 50.1 Mbd (real consumption in early 2012 is 4.3 Mbd).

Put another way, if the combined present day population of China and India attained today's OECD per capita oil consumption, their combined oil demand would increase to 104.7 Mbd from their current real world consumption of 13.6 Mbd.

Oil fear in the direction of China and India is easy to understand. China's national consumption in 2001 was 3.67 Mbd, but by the end of 2011 it was running at 9.3 Mbd for an average annual growth on a ten-year basis of 9.74%. India's average annual growth of oil demand since 2001 was more than 6%.

A few countries on the planet - for example Saudi Arabia and UAE - consume as much as 30 - 32 bcy, but there is no conceivable way that either China and India, let alone the planet's entire population, will ever reach the OECD's current average per capita oil consumption rate. We can forget that. And we can move on to talking real.

The OECD, with 14% of world population, consumes slightly more than 50% of world total oil supplies - but the problem is that non-OECD consumption is growing fast, more than compensating the sluggish oil demand growth of the OECD that is due to its sluggish economic growth.

Over the decades since the 1970s oil shocks, various long-running energy policy initiatives inside the OECD group are theoretically aimed at using less oil, and the already ten-year-old green energy quest is promoted as "able to save oil" as well as saving the planet from global warming. In reality, since the 1973/74 oil crisis, global oil demand has increased from a year-average of 59 Mbd to 89.9 Mbd (IEA year forecast) in 2012.

As we know, one sure sign of slow but possibly sustained recovery from the intense economic recession in OECD countries, starting in 2008, is that the OECD group's oil demand is starting to recover now, since early 2012.

IEA forecasts of global oil demand growth in 2012 of 0.9% or 0.8 Mbd are likely a considerable underestimate, given the 'pent up demand' factor due to slow oil demand growth, or oil demand contraction in many OECD countries since 2008. It is easy to interpret the IEA's low growth forecasts as being made with the intention of trying to put a brake on rising oil prices.

Global oil demand growth rates are declining, but for world oil supply, any growth of world demand at even 1.5% a year, sustained over more than three or four years, is impossible to satisfy, because this would create a permanent Peak Oil context.

The acid test question is: Can the world attain, and then sustain more than 95 Mbd of production? According to several major figures in world oil, such as Total Oil's CEO, C. de Margerie, sustained output of more than about 95 Mbd will not be possible.

The basic choice is therefore simple. Not on a long-term basis, but from the mid-term defined as by or before 2015-2017, oil demand cuts will need to be become constant or structural, not simply driven by recession and followed by demand recovery, itself followed by another price surge as the lowered supply ceiling is quickly reached.

As we know from data for Europe's PIIGS since 2008, sharp cuts in oil demand almost exclusively due to recession have provided a certain 'breathing space' before the next Peak Oil price ride towards $150 a barrel. Not surprisingly, however, the political blowback and economic or social damage through using all-out recession as an oil demand control tool will rise each time the trick is used.

Oil supply forecasts by agencies like the IEA and American EIA are obliged to underline the extreme low rate of net annual additions to global capacity, after depletion losses.

For 2011, using IEA data, this net addition to supply was about 0.1 Mbd, which can be compared with potential supply cuts from the slowly growing and small-sized embargoes on Iranian supply, possibly attaining 0.6 - 0.8 Mbd by July, if the embargoes are maintained. This potential supply cut can also be compared with the IEA forecast of 0.8 Mbd for total oil demand growth in 2012.

Trapped in a Peak Oil pincer where politically-decided supply cuts are no longer needed, this context being forecast on many occasions since 2009 by the IEA as probable or possible "by about 2017", the real world supply/demand situation increasingly indicates a much earlier arrival of this 'best by' date.

As indicated by the major global 'swing producer' Saudi Arabia, further increase of its net export supply may be possible, but the market price framework is one where Brent prices will be close to $125 a barrel.

The de facto solution to supply and to demand is therefore economic. This can be summarized as 'Back to the past, not future' underlining a central new fact of life for world oil, which is even admitted by 'supply boomers' such as Daniel Yergin of CERA: Oil supply growth, and very low annual rates of oil demand growth, both need high prices.

Unlike shale gas, the expansion of shale oil supplies will not be possible with low oil prices, and as noted above, the only present way to cut oil prices is through triggering a deeper and steeper recession - which is bad politics in an election year or run up to election year!

Making it certain the oil demand cuts will have to come from the OECD, economic growth in China and India through the past decade has shown little negative impact from ever-rising oil prices. "Chindia" is joined by other Asian, many African and Latin American countries, as well as the OPEC and NOPEC states, in not being particularly interested in all-out recession as an oil demand control tool that could or might crater oil prices for a short while. Their economic growth strategies are long-term.

The IEA estimate of early 2012 OECD oil demand at about 46.25 Mbd still sets the OECD's demand at slightly more than 50% of global total demand, but simply because of the growth rate differential between the non-OECD countries and the OECD group, they will soon outstrip the OECD as majority consumers of world oil.

This fact has political implications, strong economic effects, and a massive accelerator impact on "who gets what" for world oil supply in the next decade.

The question of who is able to pay for oil at rising prices is answered any time we look at US and European trade deficits with China and India, and other emerging economies. Trade surplus countries are able to import more oil at almost any price, as proven by the Asian Tiger economies in the 1975-95 period of their fastest economic growth, and fastest growth of imported oil at rising barrel prices.

The takeover of majority oil consumer status by the non OECD countries, with much higher growth rates of oil demand than OECD countries will tend to raise, not lower, the expected growth of world oil demand for a 1% growth in world GDP.

Called the "oil coefficient of economic growth", this has been slipping or declining for as much as 20 years, due to OECD dominance of global oil consumption (and declining economic growth of OECD countries), but the situation is now changing.

Even worse for the oil demand and therefore price outlook, the slow-growing and high unemployment OECD group's oil economic demand performance in the recession years since 2008 is more intensive than in previous recession troughs, according to IEA analysts comparing the post-2008 OECD recession with the recession years of 1980-1983.

The Reagan and Thatcher recession produced bigger cuts in oil demand for the same number of persons thrown into joblessness, the same number of enterprises ruined and the same number of industries de-localized: the "neoliberal oil strategy" can therefore be just as easily criticized as its economic and social strategy.

Forecasting the oil price levels needed to trigger recession - rather than economic growth through Petro-Keynesian growth effects - can compare 1979-83 oil price peaks in dollars of today's value.

These peaks attained an inflation-adjusted high of about $213 a barrel, in 1980, according to US Commerce Dept estimates. Below that price level and on balance (in the absence of deflationary and recessionary fiscal action of the present type), Petro-Keyneisan growth effects will tend to propel global economic growth.

What can be called a 'ratchet effect' completes the range of factors making it either certain or highly probable Peak Oil supply impacts, and demand factors, will drive oil prices to extreme highs, by 2015-2017 or before.

Oil demand contraction has become harder with each subsequent cut in average per capita consumption: since 2009 and even with massive unemployment, the OECD is now more oil-intensive in total consumption terms than in the Thatcher-Reagan recession years.

At the time described as "caused by high priced oil", the role of extreme high interest rates was decisive. The global power to cause economic harm, by calling a recession because of an obsession with cheap oil, is now surely and certainly slipping from the hands of OECD political deciders.

By Kiely (registered) | Posted May 04, 2012 at 10:24:52

Peak Oil can be defined at least four ways, but one way is simple: Peak Oil is when supplies and stocks are tight enough, relative to demand, to make price slides short and price hikes long.

No, Peak Oil is when we have reached the maximum rate of extraction. THAT is simple. Any other implied definition is obfuscation on your part.

If you want to establish any credibility with people who do not believe in peak oil, saying peak oil has 4 definitions and providing a convoluted one as an example is probably not the way to go about it. If you start mixing price into the definition of peak oil you muddy the water and any peak oil discussion very quickly degrades into a debate over the definition of the term, becoming just another useless exercise in semantics.

By Undustrial (registered) - website | Posted May 04, 2012 at 15:15:26

Peak oil could have a few different definitions - the absolute half-way point in total world oil extraction, the absolute production peak, or when demand begins to overtake supply. In theory these should all coincide, but in practice we're dealing with a two-century timespan and lots of other vairables, so they may not all fall on the same day.

What's important is that several major predictions (from the last decade, at least) have come to pass. First, there's been an enormous growth in the price of oil. Second, there's the big shift toward "unconventional" oil, which is far more expensive and energy-intensive to extract. Second, there's been an amazing growth in the price of oil. Third, spiking oil prices have already coincided with a collapsing economy. Those are all pretty big warning signs.

By A Smith (anonymous) | Posted May 04, 2012 at 16:22:11 in reply to Comment 76485

>> Third, spiking oil prices have already coincided with a collapsing economy.

According to the Bank of Canada...

http://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/price-indexes/cpi/

total CPI (which includes energy and food) has increased by 1.95% since 2005 (March-March).

From 01/2000 to 01/2005, when Canada avoided a recession, total CPI averaged 2.41%/year.

Even if peak oil is real, it hasn't yet bled into higher overall inflation.

Moreover, recessions have nothing to do with high oil prices, they have to do with a lack of buying and selling relative to productivity. In the following chart...

http://pragcap.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/sb1.gif

you can see that private sector savings increased in the years

1970

1975

1980

1982

1991

2001

2008

Now compare those years to this table of U.S. recessions...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_recessions_in_the_United_States#Great_Depression_onwards

You will see that they mesh nicely. In other words, recessions occur, NOT because oil prices increase, but because the private sector reduces spending and increases its savings.

Recessions are all about a switch from spending to savings, not about relative price increases.

Unlike households, federal governments have the ability to run infinite deficits, because they print money...

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-_N0Cwg5iN4

Not only that, but printing money NOW is very unlikely to create any inflation, because nominal GDP is growing extremely slow...

Nominal GDP growth by decade

1970's - 10.38%

1980's - 7.60%

1990's - 5.54%

2000's - 3.86%

First quarter 2008 to the last quarter of 2011 - 1.86%.

If peak oil is about anything, it's just a transfer of western dollars to oil rich nations. Assuming they spend those dollars eventually, this is simply delayed production in the west.

By Kiely (registered) | Posted May 08, 2012 at 12:17:53 in reply to Comment 76491

… it hasn't yet bled into higher overall inflation.

Overall inflation numbers??? Oh boy, you do like to be pissed on and told it is raining.

Take all the unnecessary "consumer goods" out of inflation and you'll see the real story. Inflation on must haves: food, fuel, heat, etc… is much higher than "overall inflation" indicates. Just the trend of dumping new consumer goods into the market at artificially inflated prices and dropping the price over time to dramatically lower but still profitable pricing has been messing with the numbers for decades, not to mention what government "tweaking" of inflation numbers has done over the same time period.

Overall inflation is similar to unemployment numbers, they are both fabricated statistics, tailor made to conceal the truth of increasingly harsh economic realities.

By A Smith (anonymous) | Posted May 08, 2012 at 13:28:33 in reply to Comment 76630

>> Take all the unnecessary "consumer goods" out of inflation and you'll see the real story.

The CPI is weighted according to what average households actually purchase, not on whether or not it is "necessary". If we calculated inflation based on what you propose, then it would be much higher, but it would also be useless in calculating the actual purchasing power of Canadians.

You may argue that consumer goods aren't necessary, but then why are people buying them? If gas/heat/food are more important than consumer goods at any amount, then why aren't people limiting their purchases to those core goods?

By Kiely (registered) | Posted May 09, 2012 at 10:39:13 in reply to Comment 76636

...then why aren't people limiting their purchases to those core goods?

Because a good chunk of the global population is programmed to be mindless consumers.

Unfortunately the poor or those on low and fixed incomes often have no choice but to limit their consumption to those core goods and as is often the case they feel the sting of these harsh economic realities first; often while those with more affluence and armed with statistics to spew are capable of still shielding themselves (mentally and physically) from the pending economic and environmental comeuppance.

Comment edited by Kiely on 2012-05-09 10:39:41

By A Smith (anonymous) | Posted May 09, 2012 at 13:39:02 in reply to Comment 76694

>> Unfortunately the poor or those on low and fixed incomes often have no choice but to limit their consumption to those core goods

Canadian average yearly inflation, from 2007-11.

http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/econ156a-eng.htm

Food = 3.38% (fresh fruit = 2.23%, veggies = 4.3%)

Clothing = -0.99%

Health/personal care = 2.21%

Rented accommodation = 1.39%

Water/fuel/electricity (shelter) = 1.92%

Public transit = 2.78%

Private transportation = 1.68%

(Costs = -2.3%, Operation = 4.37%)

As you can see, overall inflation isn't that high.

As for the poor, however, I agree that $592 is not enough. That barely covers rent and utilities. Unfortunately, middle class voters, the ones who decide elections, care more about smaller class sizes/cheaper tuition than they do about the poor.

By Undustrial (registered) - website | Posted May 06, 2012 at 23:51:11 in reply to Comment 76491

Are you honestly arguing that the five-fold rise of oil prices over the decade hasn't had an economic effect? How, under these calculations, does the ultimate supply of available oil fit in? What changes if it's infinite, or if it all suddenly stops tomorrow?

Real-world economies don't all grow just because a few companies get rich off higher oil prices, even if that drives up the GDP. Some sectors (transportation, manufacturing, etc) see little gains and enormous liabilities, yet the rest of the economy clearly can't function without them. It's called "the oil choke", and it's been referenced a few hundred times in the business press over the past few months.

By A Smith (anonymous) | Posted May 07, 2012 at 12:47:55 in reply to Comment 76535

>> Are you honestly arguing that the five-fold rise of oil prices over the decade hasn't had an economic effect?

Let's look at history. From 1970-80, nominal oil prices increased from $3.39-$37.42 ($19.71-$102.61 inflation adjusted). In that time, U.S. unemployment averaged about 6.3% and real GDP averaged 3.17%.

From 1980-90, nominal oil prices went from $37.42-$23.19 ($102.61-$39.94 inflation adjusted). Unemployment averaged 7.1% and real GDP averaged 3.24%.

I don't see much difference, do you?

By ViennaCafe (registered) | Posted May 05, 2012 at 11:19:26

The most common definition of peak oil as used by many authors and experts on the topic is when he have reached the peak of production of easily accessible, easily refined oil. It is at that point that more difficult to access, more difficult to refine oil becomes economically viable due higher prices covering the higher production costs. The expansion of tar sands production, offshore production, and Arctic drilling are all indicators we have passed that point. It does not mean we are in any danger of running out of oil any time in the near or mid-term. What it does mean is that we will pay more to waste the precious resource in our toys and that our economies, entirely dependent on oil, will continue along on ever shorter boom and bust cycles. Read this: http://www.jeffrubinssmallerworld.com/ab...

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?