Are we all guilty of pursuing the horizon? Of pursuing an end that is but a beginning the moment we reach it?

By Mark Fenton

Published January 26, 2012

Diane, when two separate events happen simultaneously pertaining to the same object of inquiry, we must always pay strict attention.

Special Agent Dale Cooper, Twin Peaks, Episode 1, season 1

The holiday season was nearing its end.

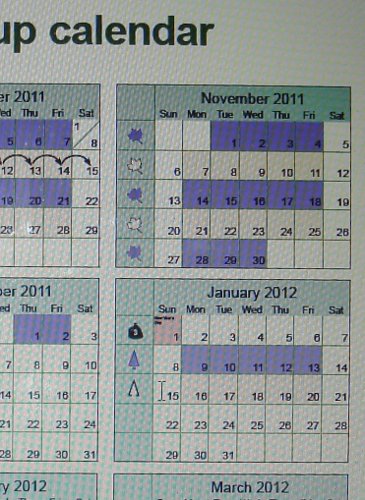

Our family belong to the set of all people who annually like to kill a healthy pine tree, bring it indoors and decorate it. But as with all recently dead things, the tree became brittle and began the rapid march of decomposition. It was time for us to dispose of the seasonal tree, as it was for many others in our community. All over the city, people were consulting The City of Hamilton Yard Waste Collection Schedule to do just that.

I marvel at and even envy the power a web maintainer has over the movement of a vast and faceless crowd taking trees from interior space to front walk.

I like to imagine this phenomenon being observed by an intergalactic anthropologist in a saucer-shaped craft. Multitudes of humans entangled with pine trees in a vigorous and prickly dance, might well be a head-scratcher. As with all power administered from a distant pod, the power of a website maintainer over civic waste disposal is seductive, yet carries a burden of conscience.

A business acquaintance I spoke with the following day had fallen and broken her wrist while grappling with her own brittle plant. She will now require surgery. While I don't hold culpable the web maintainer who mobilized an exodus of tree bearers, it is a brutal reminder that any one of us can unknowingly be the link in a chain that causes trauma of which we have no knowledge.

This distancing of responsibility from identifiable individuals is an inescapable and terrifying reality of post-industrial life. (It has never surprised me to hear of North American suburbanites who never leave their beds.) This consideration of our unwitting entanglement in the wellbeing of strangers sent me back to John Donne's famous "No Man is an island" sermon, a piece I've resolved to reread yearly on seasonal pine tree disposal day.

Incidentally, if you've been following recent shipping news - or even if you simply have a pulse - you'll no doubt be aware of the sad fate of the Costa Concordia, and I contend that Donne's sermon might well be haunting Francesco Schettino, the captain, in the wake of his ship becoming, itself, an island (to say nothing of his personal hubris).

So. In order to experience properly the last gasp of the holiday season - for aren't farewells as important as greetings? - I had downloaded a playlist of seasonal tunes, beginning with a recent Flaming Lips/Yoko Ono collaboration entitled "Atlas Eets [sic] Christmas."

(This link will inevitably go dead when this essay gets archived but I've discovered that some people need proof that I don't just make this stuff up.)

I pressed play on my iPod and began post-seasonal cleanup, picking scraps of paper, labels, etc. that had fallen under the tree in the chaos of gift opening.

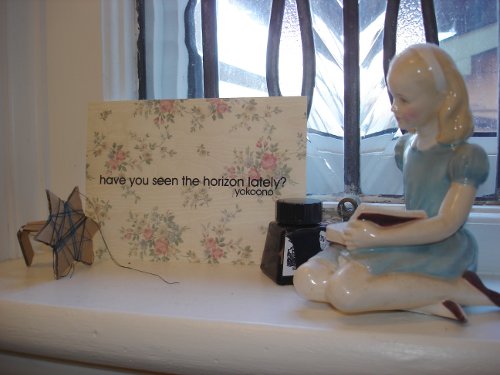

At the exact moment Yoko Ono's vocals hit the mix I picked up a postcard that had been face down since I'd received it some weeks ago, from my friend Lelde. The postcard was included in a larger package, and went almost unnoticed before being engulfed in the chaos of incoming seasonal gifts and cards. The image, set against wallpaper, consists simply of the following text which I hereby photoreproduce in its entirety.

Yoko Ono is not exactly front page news these days, and yet her name converged on me from two unrelated directions at exactly the same moment. 'I must pay strict attention,' I thought, and to this end placed the postcard on my shelf of objects for photo essays past, and present and yet to come.

In his Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle, Carl Jung describes an incident in which a patient relates a dream involving a golden scarab beetle. During the narration of the dream, the distinguished doctor hears a tap at the closed window. Adept at multitasking, he turns to assess the situation.

I opened the window and caught the creature in the air as it flew in. It was the nearest analogy to a golden scarab that one finds in these latitudes, a scarabaeid beetle, the common rose chafer (cetonia aurata), which contrary to its usual habits had evidently felt an urge to get into a dark room at this particular moment. I must admit that nothing like it ever happened to me before or since, and that the dream of the patient has remained unique in my experience.

At the risk of deflating the argument for acausal connections that I should be attempting to inflate, I am inclined to play the sceptic for a moment. Let's take the above passage apart piece by piece.

I opened the window...

One can imagine the patient pausing at the interruption to say something like "Oh, are you...Should I..." to which Dr. Jung replies casually "No, no Keep going, I'm listening. There was a scarab beetle. See? I'm all over the dream."

...[I] caught the creature in the air as it flew in.

I've caught mosquitoes in my hand, and on rare occasions a fly, and I usually mash the poor creature in the process. Never anything larger. Never any of the above when I was I was holding a Mead Notebook and Bic Grip Roller in the other hand and giving attention to the dream narrative of a troubled soul. With that combination of reflex and hand/eye coordination I will not be hustled into playing racket sports with Dr. Jung for money, that's for sure.

It was the nearest analogy to....

Hold it a sec, Dr. Jung. In addition to being so overdecorated with medical, philosophical, and anthropological suffixes that at conferences your name tag must be the size of a bib, somewhere in your academic career you picked up some entomology too? Bug names you can produce by Latin classification and in the vernacular and all while you're making notes on a dream!? And without Google?

More tellingly though, I'm struck by the loophole he slyly nudges his colleagues toward.

...the nearest analogy to a golden scarab that one finds in these latitudes... [italics mine]

This is where it gets smarmy. Not quite the insect in the dream, but the closest approximation you're going to find forcing its way, suicide-bomberlike into this particular office. (If the Doctor had a practice in Nunavit I guess, for a synchronous analogy to the beetle in the dream, he would have to settle for a polar bear lumbering by.)

I don't know about you, but when an argument contains a detail no one could possibly invent - one that, in fact, undermines the argument - I'm immediately suspicious that the detail is invented. What he's saying is, "It would be better for my argument if this had been a bona fide scarab beetle like the one in the dream, but alas it was merely a close approximation, and as a man of science and integrity I cannot misrepresent the evidence."

Call me Doubting Thomas, but I feel I'm being sold something I don't entirely want to buy.

... the dream of the patient has remained unique in my experience...

I get it. It's all about you and your research, huh, Dr. Jung? Funny we don't get anything about how this discovery helped the patient with her issues. One can only imagine the exchange that ended the session in the wake of the Doctor's 'Eureka' moment.

CJ : (clutching the insect gently to preserve it as evidence) I'm very sorry Miss -- [yes, I know, but in fairness, most doctors of that generation would have used the same condescending and sexist appellation] I'm afraid I'm going to cut our session short. Something...crucial... has just - just come up.

Ms --: What, you just got a text from a patient who's suicidal...?

CJ: Not exactly - I promise I'll make it up next session.

Ms --: (glancing at the beetle.) Oh, I see. You have an entomology paper to write.

CJ: (with a don't-women-say-the-darnedest-things chuckle he'll immediately regret) No. Though since you mention it, I did actually present a Master's thesis on the cetonia aurata which at the time gained me some degree of-

Ms --: Ooooh kay. I think I'll be taking my therapy over to Dr. Reich. Tell your secretary his office will be calling to transfer my file.

CJ: (stiffening and clearing his throat) Obviously you can do as you please by I feel compelled to warn you that Wilhelm Reich's system is detrimentally committed to the pleasure principle alone, which can only-

Miss --: Yeah. Dr. Reich's sexier than you too. At least on the admittedly tepid bell curve of psychoanalysts (and she slams the door.)

Top: Jung. Bottom: Reich (Your call.)

I stood on my driveway the afternoon following seasonal pine tree pickup looking down at the stones of my driveway.

(That figure in the bottom right corner is the family cat, who, after being AWOL for a good portion of the previous 24 hours, co-ordinated her return with an intrusion into my photographic rectangle at the decisive moment, thereby wrecking the aesthetic of 1960s minimalism that I was striving for. Coincidence? CJ doesn't think so.)

As you can see, all that remained were the brittle pine needles, scattered randomly but as though they might, like yarrow stalks, be used for divination of an I Ching hexagram.

I didn't know how to do this, so instead I thought back to Ono's directive that I look at the horizon. The only view of such from my house is gained from the attic window. And so I ran upstairs and looked outward toward it just as Atlas Eets [sic further] Christmas looped back on my playlist for the third time that day.

Yes, sometimes the horizon is hard to see, but I assure you it's there if you stare long enough between the first and second wire, positioned like a landscape painter's gridlines. The concept of horizon becomes complicated by fog. It could be the visual limit of the escarpment, or the line of trees just beyond the Fortino's Plaza, or, in more severe fog, the line of rooftops across the street.

The first and last time I flew a helicopter was when I just happened to be sitting up in the cockpit when the pilot said, "I'll let you take the controls," as though this wasn't the last thing I'd ever wanted to do.

"Place your forearm on your right knee and take the stick gently between thumb and forefinger. You won't need much pressure, it's very sensitive." I won't give you the full lesson. What's relevant is that he asked me to maintain a consistent altitude by "keeping the horizon in the centre of the windshield..." adding, a moment later, in case my vocabulary didn't contain the word 'horizon.'

"That's where the ground meets the sky," and then, having not attended a minute of ground school and having had only 45 seconds of in-flight instruction, my instructor buried himself in a map and let me just drive the thing. (We're both still here.)

Expressed in such simple language his directive made me consider the word 'horizon.' Since the sky isn't anything measurable, it's really about where the ground reaches a visual limit against nothing. If you actually went to the place you saw the horizon it would be ridiculous to think of it as such, since once you were there another horizon would appear.

As I flew the aircraft in some state of denial that this was really happening, I recalled this startling poem by Stephen Crane.

I saw a man pursuing the horizon;

Round and round they sped.

I was disturbed at this;

I accosted the man.

"It is futile," I said,

"You can never - ""You lie," he cried,

And ran on.

Because I was flying an aircraft at this moment, it occurred to me that the only person who could conclusively reach the horizon would be a pilot, but only if she or he aimed the aircraft to a point just below the summit of a ridge, slamming the aircraft, everyone in it, and most importantly the pilot's own line of sight, into the last immeasurably small distance below the point where a new horizon would appear beyond it.

That this reaching of the horizon would be the pilot's final conscious act fit the fixated madness of Crane's running man. It gave me the jitters and is, I think, an explanation of why I was at that moment subconsciously aiming the helicopter upwards into the soft and infinite sky, at which my impromptu flight instructor lifted his head out of his map, took control and said, "I'm just moving you down a bit. For some reason you were starting to gain altitude."

Are we all guilty of pursuing the horizon? Of pursuing an end that is but a beginning the moment we reach it? Should we cut Francesco Schettino some qualified slack here? Is there a better metaphor than a cruise ship sliding atop our spinning sphere for the delusion that moving quickly over the global surface means attaining any meaningful destination whatsoever?

Can this realization produce an apathy that ultimately imperils the ship? "These people aren't really going anywhere. What difference does it make if I just point the thing between these rocks and ...oooooh -!"

In his introduction to the Wilhelm/Baynes translation of the I Ching, Carl Jung describes synchronicity (for which I Ching is a working model) as taking "the coincidence of events in space and time as meaning something more than mere chance, namely, a peculiar interdependence of objective events among themselves as well as with the subjective (psychic) states of the observer or observers."

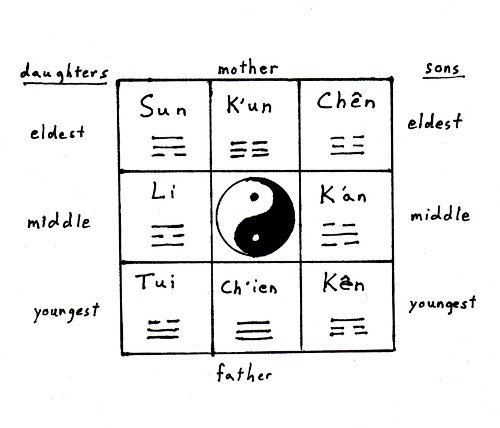

Some years ago my mind was deeply immersed in the workings of the I Ching, in particular its eight randomly occurring "trigrams" which were equated to the roles of an eight member family, consisting of a father, mother, three daughters and three sons.

I happened to be visiting a friend in Toronto, and on his wall was a poster of all the characters in the '70s TV show, The Brady Bunch, which formed an exact correlative for the I Ching family.

The effect was as jarring to me as Dr. Jung's experience with the half-assed scarab beetle: a near perfect correlation between two kinship structures. That there is almost certainly no causal relation between the I Ching and the creators of the TV show simply confirms the play of synchronicity.

I'm surprised that googlewacking Brady + "I Ching" produced nothing of either use or interest to my argument (other than that I accidentally missed hitting the spacebar between 'I' and 'Ching', which elicited the query "did you mean Brady + itching?").

So clearly no one experienced the same overlap: having the giddy Brady faces intrude unpleasantly, like an itch, during ruminations on an early Chinese symbolic system. In other words no one else experienced that particular "...interdependence of objective events among themselves as well as with the subjective (psychic) states of observer...." that Jung reiterates throughout his writings until it starts to feel like a mantra.

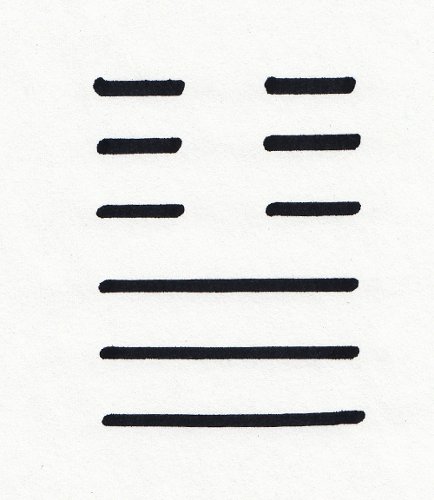

Because the very notion of I Ching is circular, there are many logical ways to denote the family of eight trigrams from which all 64 hexagrams are derived, but the chart I've drawn below is as standard as any. (Incidentally, I Ching is generally regarded as the first binary system. Rather than zeros and ones, all its information is derived from either a solid horizon or a broken one.)

(Damn! Have you ever noticed that once the word "itching" is mentioned you feel itchy all over? Now I actually am going to have to google "itching" and probably purchase some ointment for epidermal relief.)

For reasons I don't entirely understand-given that my knowledge of written Chinese is limited in the extreme-when you throw the I Ching you draw from the bottom to the top which explains the seeming inversion of a patriarchal family structure: Ch'ien (the father) on the bottom and K'un (the mother) at the top.

When you study the interpretation of hexagrams you find that some combinations are more "fitting" within a traditional construct of Chinese family relations, and these relations have to do with the family hierarchy of father, mother and order of children.

Ch'ien is represented by three Yang (solid) lines and K'un by three Yin (broken) lines. (Solid is male, broken is female-though of necessity I'm simplifying the qualities of solid versus broken lines here). Ch'ien represents heaven and creativity. K'un represents earth and receptiveness.

One of the most auspicious hexagrams one can throw is three solid at the bottom and three broken at the top. Thus:

This puts Ch'ien (heaven) at the bottom and K'un (earth) at the top, which is sort of backwards to how we'd put them in the West, but it makes sense in terms of how the hexagrams are built. (By contrast, K'un at the bottom and Ch'ien at the top is a real difficult hexagram to have to navigate. Things are out of balance. I threw it once and prayed that I wouldn't be asked to fly a helicopter anytime soon.)

I hadn't noticed until now that the Brady square puts Mike at the bottom and Carol at the top! I'd have expected the patriarch on top, even as late as 1970, but as a correlative to I Ching Mike is exactly where he should be, as is Carol and all is good in the world and I'm pretty sure CJ would've been canceling sessions had he stumbled on this acausal "...interdependence of objective events..."

(I can't tell you how much I enjoyed plunking in that image right after typing "...interdependence of objective events...")

So far so good. But I was puzzled as to what I should make of Alice in the middle. Then when I was surfing trigram charts I noticed that a Yin Yang symbol is sort of ubiquitous as a central design element. The Yin Yang symbol is of course an infinity symbol, about the balance of doing and not doing, the essential male and female in everything, and about marshalling the hidden powers within us.

The somewhat butch, post-menopausal Alice is perhaps the least sexual character in the history of television. Or is she? (Again, your call as to where she fits on the Dr. Jung, Dr Reich sexiness curve). Perhaps she contains Yin and Yang in equal portions. Androgynous in the mythic sense.

In the Western tradition, the best example I can think of is Tiresias who kept getting his sex changed because he upset Zeus and Hera. The difference being that Tiresias mostly mopes about his lot where Alice has more of a peppy, "can do" attitude. (True confession: there were things I really liked about the American century.)

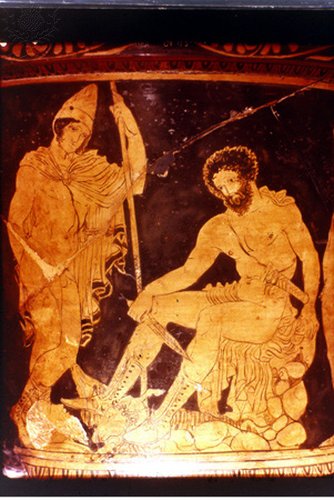

To push the connection into visual terms, I'm struck by this picture of Odysseus consulting the ghost of Tiresias (right) on some piece of Attic pottery. I see in Tiresias some of Alice's frazzled stoicism.

If you're a Civilization and its Discontents era Freudian, you might say Alice's pleasure principle is fully sublimated, which makes her the bedrock of civilization.

As a non-family member (I don't think she's a relative though my knowledge of the blended-family-Brady-mythos is woefully limited) she has, paradoxically, the least status in the home while at the same time having the most power in the machinery of the home. A sort of eye of the hurricane, all over the appliances and household means of production and not mired in the gooiness of the family romance that surrounds her. (I contend that she'd do better at navigating a cruise ship than Francesco Schettino, as well as being a real fun cruise host/ess.)

I teach Taiji and will consider using her as a metaphor for the strength we must learn to access in the core of our bodies, invisible, but the source of our greatest power. Her position in the central square is fitting.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?