Though Hamilton had its own sources of stone in the nineteenth century, some stone was imported, at first by ship and later by rail. Local stone was difficult to carve, and not always suitable to changes in architectural style.

By Gerard V. Middleton

Published December 11, 2011

Though Hamilton had its own sources of stone in the nineteenth century, some stone was imported, at first by ship (Ohio sandstone, Queenston stone, Indiana limestone) and later by rail (east coast "brownstone," Credit River sandstone, Tyndall stone). Local stone was difficult to carve, and not always suitable to changes in architectural style.

For the purpose of this article, "imported stone" includes not only stone brought from the United States (and other countries) but also stone from elsewhere in Ontario (e.g., Kingston, Queenston, and the Credit River). Hamilton had its own sources of stone (Whirlpool sandstone from the face of the escarpment; Eramosa dolomite from quarries on the Mountain), but even in the mid nineteenth century it was easier to bring some building stones to the city by ship (notably the Ohio sandstone).

Most imported stone ("brownstones" from New England or New Brunswick; Indiana limestone) were not used much before 1880-1910. Others (Credit River sandstone; Tyndall stone) were used mainly after 1920, and brought in by rail.

Queenston stone is a strongly crinoidal dolomitic limestone, until recently quarried at Queenston from outcrops of the Gasport Formation. The quarry is currently being redeveloped as a residential, recreational and heritage site: see Masterplan.

Several quarries were developed over the years, and produced a variety of stones, some very coarse (suitable mainly for heavy construction), some finer, more compact, and suitable for carving. The coarser variety was used to construct The Burlington Lighthouse, on the beach just south of the canal.

The stone lighthouse was built in 1858 (at a time when this location would have been considered part of Hamilton). It replaced a wooden structure that had been built in 1837 and burned in 1856. It is 55 feet high, and was in use until 1961.

It is easily the first structure in the Hamilton region built from this stone - which was also used in many other lighthouses (Toronto, 1806; Buffalo, 1837).

Figure 1. The Burlington lighthouse, built of Queenston stone in 1858.

In the nineteenth century, the fact that Queenston could be quarried in large (metre size) blocks, made it particularly useful for industrial purposes, and it was extensive used in the locks of the second and third Welland canals, and in railway bridges and embankments. It was also used for buildings in the Niagara region: see Guide [PDF].

In the city of Hamilton it was not much used in buildings until the twentieth century, when it had to compete with Indiana limestone. The Indiana limestone is a better stone for detailed carving, but fine carvings, mainly bas reliefs, can be seen on several Hamilton buildings: see ACO Exhibit.

Among the earliest buildings that used Queenston stone are the Cathedral Highschool (1928), and Bank of Montreal in Hamilton (1929), both built by J.M. Pigott; the high school has elaborate carvings over the main door.

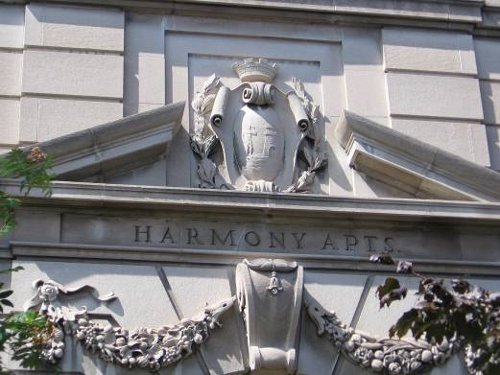

Other significant buildings include 360 James St N., the Liuna Station, originally the CNR station (1931), the TH&B Station (1933) and 245 Bay Street North, the Harmony Apartments (1935, see Figure 3). Minor use can be seen in earlier buildings, e.g., the Armouries, built in 1907.

Figure 2. Old Bank of Montreal building, built of Queenston stone (on a granite base) in 1929.

Queenston stone was widely used only much later, when it was used in the Burke Science Building (1953, enlarged several times to 1969), the Hodgins Engineering Building (1958), Whidden Hall (1959), the General Sciences Building (1962) and the Bourns Building (1968) at McMaster University; and also at the Teachers' College (1955, now part of McMaster).

At the Queenston quarry, dimension stone was no longer produced after the 1970s, so when the later buildings and extensions were built at McMaster, Queenston stone was no longer available. Wiarton stone (Eramosa from the Bruce Peninsula), artificial stone, or concrete was substituted.

In redeveloping the quarries, the new owners are making limited supplies of the stone available for restoration of old buildings.

Figure 3. Carvings in Queenston stone on the Harmony Apartments, built in 1935. It is rare to see such detailed carvings in this stone.

Kingston stone is a fine-grained, hard, pure white limestone, of Ordovician age. It was brought in as ballast to many communities along the shore of Lake Ontario, but is rare in Hamilton.

It can be seen in the TH&B Tunnel at Park St. The original tunnel built in 1895 for the Toronto, Hamilton and Buffalo Railway had an arched opening which has since been removed for widening. It was built to provide both a passenger and freight service directly to Buffalo. The stone embankment of Kingston limestone dates from the original construction.

Figure 4. TH&B tunnel embankment (at Park St), built of white Kingston stone in 1895.

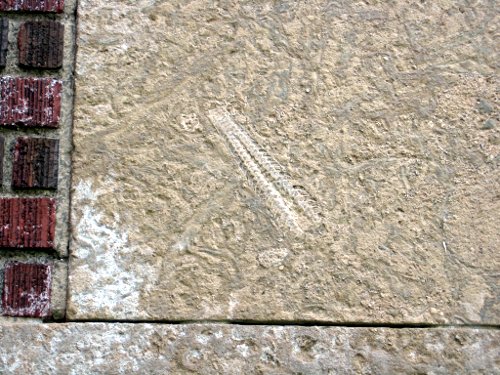

Figure 5. Detail of Kingston limestone, showing vertical structures produced by organisms burrowing in the Ordovician carbonate muds.

Another, earlier, use in a railway embankment can be seen at the bridge on King Street in Dundas, built in 1851. Also in Dundas, the "Bluestone" Presbyterian church, a modest building of Kingston stone (derived from ship ballast) was built in 1846, and still exists as part of the Legion Hall (Newcombe, 1997, p.89) though it is now mainly covered in white plaster.

85 King Street East (the Desjardins Cottage) is a stone cottage, built close to the terminus of the Desjardins canal. The front is built largely of blocks of Kingston limestone, presumably brought in through the canal as ship ballast. Examples from further afield include the Anglican Cathedral in St Catharines, and the Gooderham and Worts distillery in Toronto (built 1860).

Ohio sandstone, also known as the Berea sandstone is a widely used sandstone of late Devonian to early Mississippian age. It was the first imported stone in common use in Hamilton. It is a freestone; that is, it can be cut in any direction, is relatively soft and weathers to an attractive golden brown colour - so it was valued particularly for carving in the surrounds of doors and windows.

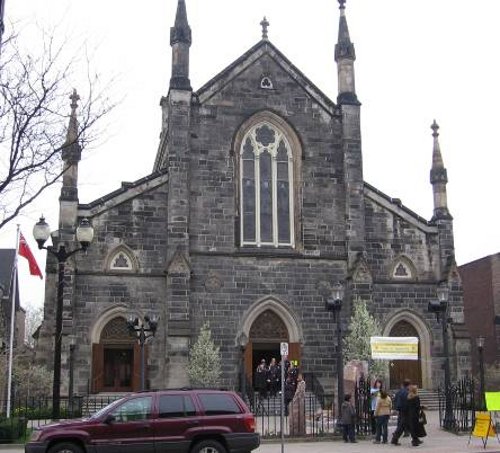

Figure 6. Christ Church Cathedral; the façade was built in 1854 of Ohio sandstone, which has been much discoloured by "black soiling" due to urban air pollution.

It was used in the Customs House in 1860, in Christ's Church Cathedral in 1852-1876, in the now-demolished Hamilton Provident and Loan building in 1880, in the Steeple of St. Paul's Church in 1857, in the tower added to the Central School in 1891, and in lesser quantities in churches for carved doorways, etc.

Figure 7. Customs House, built 1860 of Ohio sandstone, which was finished in several different styles. Note the pleasant golden colour.

Figure 8. Detail of the stone at the back of the Customs House. Here, the stone blocks were oriented with the bedding vertical, and frost action has caused the surface of one block to flake off, revealing fossil ripple marks.

Figure 9. Carved grotesque head, moved from Arkledun (built in the late 1840s) before it was demolished in 1930. The stone is Ohio sandstone. Photo by Nina Chapple.

Figure 10. Carvings in Ohio sandstone on the main door, St Paul's Church.

Indiana limestone is a pure, grey limestone, of Mississippian age, generally fine to medium grained. It is one of the most widely used building stones in the world. Though it may display faint cross-bedding, it is a freestone that may be cut in any direction. It is soft enough to be carved, but strong enough to sustain heavy loads.

As early as 1907, the Terminal Station (now demolished) was built using Indiana limestone, and it was used for the Landed Banking and Loan building in 1908, and the Carnegie Library in 1913. It became popular in the late 1920s and 1930s, mainly for decorative use (because it can easily be carved). Examples can be seen in the older buildings at McMaster, and at several local high schools.

Figure 11. Carnegie Public Library, built in 1913 from Indiana limestone.

Figure 12. Main door of Memorial Collegiate, built in 1919 of red brick and Indiana limestone. This was one of the first of a series of schools ornamented with elaborate carvings.

Credit River sandstone, also known as Credit Valley sandstone: In the 1880s, a new source of Whirlpool sandstone - the Credit River quarries - became available, due to the construction of the Credit Valley Railway in 1872-1879. The rare chocolate red ("brownstone") variety, used in the Provincial Parliament building in Toronto, was also used in Hamilton, for Central Collegiate built in 1897 (now demolished).

Most of the buildings using Credit River sandstone, however, used the grey variety and it only become popular in the 1920s and 1930s. Cathedral High School built in 1928 was one of the earliest, followed by Westdale Collegiate, built by Joseph Pigott in 1931, and many others.

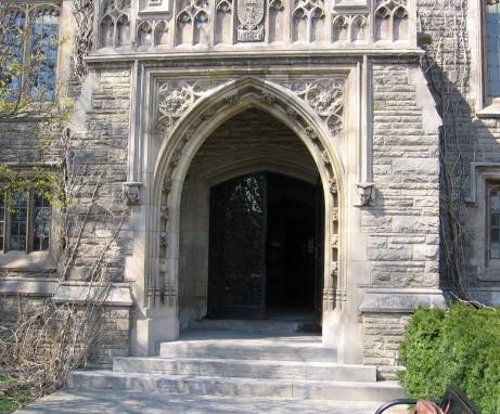

The early buildings at McMaster (University Hall, Hamilton Hall, Edwards Hall, Wallingford Hall) were all built in 1929, making use of Credit River sandstone and Indiana limestone. They were designed by a Toronto architectural firm, and followed a pattern previous established at the University of Toronto by Knox College (1915), Hart House (1919) and Trinity College (1925).

Figure 13. Doorway at University Hall, McMaster University, built in 1929 from Credit River sandstone (rock face, small blocks) and Indiana limestone (door surround and carvings).

Figure 14. Detail of Carving (in Indiana limestone) and Credit River sandstone blocks, University Hall, McMaster University. Carving by William Oosterhoff.

The carvings at McMaster were described in detail by Graham (1988). They were carved by William Frederick Karel Oosterhoff (1895-1962), who was appointed Parliamentary Stone Carver in Ottawa in 1949. He was also responsible in Hamilton for carvings on the James Street North Station (1930), and the Bank of Montreal (1929), as well as carvings at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto.

Triassic "brownstone." In the late 19th century the Richardson Romanesque Revival style became popular. It was introduced in Buffalo in 1870 and rapidly spread to other cities in the northeast US, particularly New York.

The first Toronto buildings in Romanesque style were built in the 1850s, and the Richardson variety was introduced in1886-8 (Mikel, 2004, p.84). Though brick or a light coloured stone could be used (e.g., University College, Toronto, built from Credit River and Ohio sandstone in 1859), most buildings made use of "brownstones," reddish brown sandstones generally derived from the Triassic basins in the USA (Newark and Connecticut) and New Brunswick.

The term "Triassic" is actually inaccurate, as much of the sediment in these basins is now known to be Jurassic in age: see Newark. The building stone is also known as Portland stone

Figure 15. Main doorway of the Stinson Street School, built in 1895, showing the use of two differently coloured "brownstones," as well as red brick (second floor).

Most of the buildings built in this style in Hamilton have not survived. The Birks building built in 1883 (now demolished) was designed by a Buffalo architect (Waite). He used Connecticut brownstone in this building and also in the Bank of Hamilton in 1890 (now demolished).

The same stone was used by W.P. Wilton in the old Hamilton Spectator building in 1898 (now demolished). The old City Hall (1891-1930s) was also in this style. Local architects William Stewart and his son Walter designed Central Collegiate (1897, now demolished) and several other buildings in this style.

Figure 16. Detail of the window surround and carving on the Hendrie House, designed by W.A. Edwards in 1892. Brownstone and red brick.

The last surviving major public building built in this style is the Stinson Street School designed by Alfred W. Peene. For views of Hamilton's early schools, many built in red brick in a style influenced by the Romanesque Revival, and all now demolished, see postcards. A marked change away from this style of school buildings took place in 1914.

The main surviving brownstone houses include the Myrtle Hall, now part of the Scottish Rite building built in 1895, and Ravenscliffe, built in 1880. Brownstone survives as trim in several other surviving buildings. 252 James Street South (Hendrie House, aka Tunis Griffiths Manor) now the Mercedes Spa is a red brick house, with a slate roof and window trim in a "brownstone" (Triassic sandstone) imported from the USA or the Maritimes. It was built in 1891-1892 and the architect was W.A. Edwards. (Shaw and Grimshaw, 2004, p.142)

Tyndall stone (an Ordovician mottled dolomitic limestone quarried in Manitoba. The characteristic mottles resulted from the activity of boring organisms. It can be seen every day on TV, because it was used in the Parliament buildings in Ottawa.

1284 Main Street East (at Ottawa), the Delta Collegiate was built in 1924, of red brick, with extensive use of Tyndall stone. Marble from Phillipsburg, Quebec was used for the interior stairs.

Figure 17. Main door, Delta Collegiate, built in 1924 from Tyndall stone.

Figure 18. Detail of Tyndall stone at Delta Collegiate, showing fossil (cephalopod), and mottled texture.

The Dundas District Public School was designed by William J. Walsh and built in 1928 of black and red brick, but with doorways and ornamentation using Tyndall stone. The carvings, however, appear to be in a different stone.

The first high rise building in Hamilton, the Pigott Building, 36-40 James Street South, built in 1929, (Manson, 2003, p.78-79) was also constructed from Tyndall Stone: see Pigott

Many churches and schools constructed in the 1930s or later used a combination of Credit River sandstone, Indiana limestone, and brick or other stones. The sequence: Credit River sandstone and Indiana limestone, followed by Queenston stone (followed now by Wiarton stone, or artificial stone) is also well illustrated by the buildings on the McMaster campus.

Graham, R.P., 1988. The Carvings of McMaster University. McMaster University Press, xlv p.

Manson, Bill, 2003. Footsteps in Time: Exploring Hamilton's Heritage Neighbourhoods. Burlington ON, North Shore Publishing, v.1, 168 p.; v.2, 2006, 59 p.

Mikel, Robert, 2004. Ontario House Styles: The Distinctive Architecture of the Province's 18th and 19th Century Houses. James Lorimer, 128 p.

Richards, Larry Wayne, 2009. University of Toronto: the Campus Guide. Princeton Architectural Press, 259 p.

Shaw, Susan Evans (with photography by Jean Crankshaw), 2004. Heritage Treasures: the Historic Homes of Ancaster, Burlington, Dundas, East Flamborough, Hamilton, Stoney Creek and Waterdown. James Lorimer, 160 p.

Williams, David B., 2009. Stories in Stone: Travels through Urban Geology. Walker & Co., 272 p. (See this book for more on Indiana limestone, brownstone, and other US building stones). See also his web page

By Robert D (anonymous) | Posted December 11, 2011 at 20:58:14

I find this whole series of articles on stonework in Hamilton exceedingly interesting given that it's not at all related to my field of work.

Any thoughts of getting a walking tour group together?

By Robert D (anonymous) | Posted December 12, 2011 at 09:22:53 in reply to Comment 72133

Wait...why did someone downvote this? Spite?

By TnT (registered) | Posted December 11, 2011 at 23:16:01

Did you neglect to mention that people could head over to city hall and see the imported marble…oh never mind.

By get real (anonymous) | Posted December 12, 2011 at 08:57:31 in reply to Comment 72135

You mean "Ferguson Stone"?

By Tim (anonymous) | Posted December 12, 2011 at 09:06:34

Hamilton has cultural and historical riches that are known, celebrated and valued (and perhaps even 'exploited') by far too few. Thanks Professor for making a few more of us aware of what some of these attributes are.

By Undustrial (registered) - website | Posted December 12, 2011 at 09:10:48

Agreed, Robert, I'm totally captivated by this series for reasons I really can't explain.

The biggest question I'm left with here is why stone construction stopped. Was it simply the cost/difficulty, the introduction of new cheaper alternatives (ie: concrete) and changing tastes? Or were accessible quarries depleted of reasonable size/quality stone? How practical is this kind of construction today?

By BobInnes (registered) - website | Posted December 14, 2011 at 21:22:22 in reply to Comment 72146

Stone is 'undustrial'. (couldn't resist!)

Cheap energy - and industry - makes concrete more economical.

(couldn't resist again - my bad, please forgive)

By Kevin (registered) | Posted December 12, 2011 at 09:26:05

I agree, I find these pieces fascinating.

By David Williams (anonymous) | Posted December 12, 2011 at 12:09:18

Gerald,

Great article. Always fun to learn more about building stone in other parts of the world. A couple of additional points. The Indiana, or Salem, Limestone is quite rich in fossils, including brachiopods, crinoids, and bryozoans. For those interested in movies, the stone had what I consider to be a starring role in the movie Breaking Away. In regard to the brownstones, another feature to look out for is dinosaur tracks. One of the best dinosaur track collections in the world, in Amherst, MA, has many many trackways from the brownstone quarries in Portland, Connecticut, the largest source of brownstone in the United States.

Cheers,

David

p.s. Thanks kindly for mentioning my book Stories in Stone: Travels Through Urban Geology

By logonfire (registered) | Posted December 12, 2011 at 13:44:31

A very interesting article. Hopefully there are more to come.

Thanks, Gerry.

By GerryM (registered) | Posted December 12, 2011 at 15:03:23

Why did the use of stone decline?

All the reasons suggested have some validity. There are now no local quarries producing building stone in Greater Hamilton: the nearest source for dolomite is Wiarton, and some sandstone is still available (at a price!) from the Credit River.

Modern methods of construction use cut stone for facing, not for load bearing in buildings. Older examples included the Pigott and Bank of Montreal buildings, and recent ones can be seen on Wilson Street in Ancaster.

At the time the Dundas Town Hall was built it was (marginally) cheaper to use stone than brick, but the reverse is now true, by a wide margin. And no doubt also cheaper again to use concrete and glass.

A recent article in the G&M pointed out that southern Ontario is even running out of places to quarry crushed stone, at economical prices. To look on the bright side (it is the Season, after all!) perhaps this will stimulated the reuse of old buildings, rather than tearing them down for landfill. Two local examples, in process: the Dundas Post Office, and the Dundas District Public School.

Comment edited by GerryM on 2011-12-12 16:33:35

By Undustrial (registered) - website | Posted December 12, 2011 at 21:13:20 in reply to Comment 72170

Sad, that in an age of trucks and jackhammers we can't accomplish the same feats as those with horses and chisels. I suppose when the trade started to vanish, the market for advanced stone-cutting machines went with it.

What kind of tools would a modern stone-worker use? Blacksmiths have pneumatic hammers, road crews have concrete saws and drill-bits, etc. Has this led to more favourable economics than in the past, or simply been drowned out by other rising costs?

The saddest example I know is how much of our old city hall (James St.) sits strewn about the King's Forest golf club.

By highwater (registered) | Posted December 12, 2011 at 17:05:00 in reply to Comment 72170

Another issue could have been the shortage of skilled labour. Even back in the '30's when stone was still being widely used in construction, stone cutters had to be brought over from Europe as there were not enough skilled local tradesmen to do the work.

By unconflicted (anonymous) | Posted December 12, 2011 at 18:22:56

"You mean "Ferguson Stone"?"from get real, above-- Did uncle Lloyd ever say out loud that he worked for years for a company owned by a cement company, and if Ferguson didn't say that, why not? What did he have to lose? He would still have been in the debate, and maybe even got his cement up on the building anyway. In some cities stating these things just by way of disclosure--not even conflict--is normal. (What's "normal"?)

By ScreamingViking (registered) | Posted December 12, 2011 at 20:31:30

I agree - these stories are terrific to read and I enjoy them immensely. The setting for Hamilton's history is just as important to me as the people and activities that comprise it.

Re: The buildings that were demolished, what became of the stone? Was it recycled/recut and used for other buildings? The second saddest part of the City Hall cladding saga was what became of some (most?) of the old marble panels... I recall reading that someone bought a bunch and crushed them to line a ditch on their property.

By -Hammer- (registered) | Posted December 12, 2011 at 23:20:37

This is the kind of "artistic" article I like seeing at Raise the Hammer. It pertains directly to Hamilton, it contains well researched facts and good photography to illustrate points and notes of the architecture it's talking about and comes across as feel good interesting facts, not an essay on intangible, whimsy notes of how society is collapsing.

Well written and well done.

As a side note, I actually like the appearance of the Ohio sandstone and whirlpool sandstone for the "blackened" effect they have on some of the buildings in Hamilton. It adds a certain Gothic charm to the various churches that seem to utilize it. Not as much a field-stone, which I fell in love with driving along the shore, looking at the cottages between between Port Elgin and Southampton, but I like them all the same.

By Tim (anonymous) | Posted December 13, 2011 at 03:12:02

Some of what appears to be stone on modern buildings is actually half-depth faux stone made of concrete and mechanically fastened to plywood or OSB sheathing at the back. Even the mortar, if there is any used, is often cosmetic.

The costs to maintain and refurbish the facades of these old stone buildings must be enormous. In my neighborhood the Hendrie House (aka Tunis Griffiths Manor, aka Mercedes Spa) is in rough shape in places at the back, by the chimneys and near the roof line. I can't conceive how rent at a place like that would generate enough revenue to finance a restoration.

By Undustrial (registered) - website | Posted December 13, 2011 at 17:21:45 in reply to Comment 72189

But how often does this need to be done?

I've seen a lot of very nice concrete work lately, but also lots of examples of what that'll look like in five or ten years. Concrete weathers much faster, and no matter how stone-like you make the surface, it's always concrete underneath, which will show up eventually.

By Tim (anonymous) | Posted December 14, 2011 at 02:55:04 in reply to Comment 72250

^ Agreed, very much. A short-term manufactured "solution" if there ever was one.

By TB (registered) - website | Posted December 14, 2011 at 07:20:29 in reply to Comment 72258

Actually the Romans invented concrete around 2000 years ago and the Pantheon's dome is still the world's largest unreinforced concrete dome.

By TnT (registered) | Posted December 14, 2011 at 18:00:21

Professor, is there a difference between modern Portland ( I hope that is right name) cement and Roman cement? I had a driveway done and the guy explained to me that cement of the ancient world was different.

By GerryM (registered) | Posted December 14, 2011 at 20:55:48

I am no expert on cement -- it is now a highly technical subject and the experts are mainly civil or chemical engineers. There is, however, an excellent Wikipedia article which gives the history and references to technical details.

In the Mediterranean, the Romans and others used a cement made by mixing lime with volcanic ash (called pozzolana). Portland cement generally used lime and an inert mix, such as sand. Other materials can be used instead of sand, which do react chemically. Some forms of limestone ("cement rock" -- including one bed that was mined near Niagara Falls) can be burned to form a lime which acts as a cement without additives, because the limestone itself contained substantial amounts of clay.

When the first canals and lighthouses were built in the UK (and soon after in the USA and Canada) the ancient techniques used by the Romans were re-discovered, as it was necessary to produce a "hydraulic cement" that would set quickly, and under water. In fact, the beginning of civil engineering in the US dates from the construction of the Erie Canal.

I doubt that the best modern cements weather any faster than natural stone -- but, as I have written, I am no expert!

By GerryM (registered) | Posted December 15, 2011 at 07:55:11

A further clarification: quicklime is the term for calcium oxide produced by heating limestone (or dolomite) to drive off the carbon dioxide. Simple quicklimes can be used to make cement or mortar, by mixing with sand or other materials. But Portland cement is produced by burning a mixture of limestone with silica bearing materials: this yields calcium silicate "clinker" which is then mixed with gypsum and other materials and ground to a powder to produce Portland cement.

Comment edited by GerryM on 2011-12-15 07:58:13

By Undustrial (registered) - website | Posted December 15, 2011 at 12:26:27 in reply to Comment 72291

This kind of cement is indeed ancient and very well known. Even Thoreau talks about making his mortar this way in Walden, while building his hut near the pond. Without something like this for mortar, stone construction is much more complicated.

The genius of brick or stone construction of this type is that it uses relatively little cement to produce very strong structures. It even works with bottles or cans. The mortar can be anything from simple cements like quicklime to sand/clay mixes like cob, as it doesn't need to be strong enough to make up the whole wall.

Cement is handy for construction, but over-using it leads to fairly fragile and short-lived construction in most cases. Steel re-enforcement helps, but even that crumbles before too long. It's a marvel of modern science that we can build skyscrapers, bridges and foundations out of something which was once only mortar, but we have a long way to go if we're going to achieve structures which compare to the architectural legacy left by those who came before us. 1800s stone buildings were very well designed because at that point masonry was a few thousand years old, and had the chance to watch structures weather over centuries.

By AlexCavity (registered) - website | Posted April 03, 2012 at 03:02:23

I have to say that this article is definitely informative. I never knew that there was so much to know about what a wall is made up of, and that there were so many different types of stones, and that not all of them were suitable for architectural purposes. Thanks for sharing.

By A.W. (anonymous) | Posted December 02, 2014 at 17:52:53

Forgive me if this sounds like spam, but I carve stone for building purposes, what is called a "banker mason" in the trade. People who do this work still exist, they are in very short supply, but they do exist. The problem with most buildings made from cut stone is the lack of knowledge in how to properly maintain it, ie mortar mixes for pointing the work, cleaning pollution etc. and the cost of replacing it should it fail. The fact of the matter is that it is extremely expensive to replace or even re tool. I am having an uphill battle in our part of the world finding anyone who even knows that this work needs to be done, let alone pay for it. This is a subject near and dear to my heart, but always angers me when brought up, people always want their beautiful cut stone buildings and lament at their loss, (rightly so,) and I could help the public out... yet I'm here on a Tuesday afternoon at my dining room table unemployed lurking the internet. I know my problem is not unique and forgive me if I sound bitter, I just came across this forum on my travels on google images (looking for inspiration,) and needed to vent. Grateful that you're letting me vent, all the best to you out there in Hamilton.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?