The 19th century men who worked with stone described themselves as builders, quarry men, stone cutters, and either masons or stone masons.

By Gerard V. Middleton

Published August 31, 2011

The men who worked with stone described themselves as builders, quarry men, stone cutters, and either masons or stone masons. Builders used wood and brick as much as stone, and masons often laid bricks. Stone cutters were skilled quarrymen.

Figure 1. An old French illustration of a stone cutter (poem translation: If you would build a superb edifice/You will need my trade and craft/ There is no finer worker/ To square stone, there is none better). From WikiGallery.org

Two main sources provide us with some information about stone domestic houses and the men who worked with stone in nineteenth century Hamilton: The Census, and the City Directories. They show that the number of stone dwellings in the city was already 150 in 1851 and doubled in the next ten years, after which it remained constant - not because no new houses were constructed, but because old ones were torn down as fast as new ones were built.

In the City, the numbers of stone workers was about 100 in 1851, decreasing only slightly to 1871.

| Region\Date | 1851 | 1861 | 1891 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barton township | 17 | 38 | 55 |

| Beverly township | 19 | 45 | 117 |

| Flamboro E (incl. Waterdown) | 13 | 38 | 79+29W |

| Flamboro W | 20 | 25 | 59 |

| Dundas town | 28 | 34 | 43 |

| Ancaster township | 16 | 41 | 61 |

| Hamilton City | 150 | 322 | 324 |

Table 1: The number of domestic houses built of stone in each community of Wentworth County. The figure for Waterdown is shown only for 1891.

In nearby townships (most now included in the new City of Hamilton) growth was less spectacular, but steadier, a pattern that has continued to the present. Overall, there were more stone buildings in greater Hamilton than in most other parts of Ontario (except the Cambridge/Waterloo/Guelph region).

The 1851 census (of Canada, before Federation) listed 1,500 stonemasons, compared with 7,600 carpenters, 300 plasterers and 300 bricklayers. By 1871, the number of stonemasons had increased only to 2,600, compared with 15,000 carpenters, 800 plasterers, and 800 bricklayers.

Of course, construction of stone houses required the services not only of stonemasons, but also of carpenters, as the porticos, verandahs, roofs and interiors were constructed mainly of wood.

No doubt many rural settlers were quite capable of doing their own carpentry and brickwork; but stonemasonry was more demanding and required the attention of a craftsman. The census data also show that stonemasonry was an imported skill, not one that was home-grown.

The census for 1851 and 1871 listed not only place of birth and ethnic origin, but also age and religion. In the City of Hamilton almost all were immigrants, predominantly from England, Ireland, and Scotland. Among those from Ireland about half were Catholic.

It is a common misconception that most of the skilled stone masons or cutters were Scottish: this was not true in Hamilton or the Niagara peninsula, though it was in some other communities, notably Galt. And incidentally, almost all the architects were English.

| Birthplace\Date of Census | 1851 | 1871 |

|---|---|---|

| England | 39 (39%) | 27 (31%) |

| Ireland | 22 (22%) | 18 (20%) |

| Scotland | 32 (32%) | 26 (30%) |

| USA | 3 (3%) | 5 (6%) |

| Total | 100 (incl. 4 others) | 88 (incl.12 others) |

Table 2. Birthplace of stone workers (quarry men, cutters, masons) in the City of Hamilton.

The data strongly suggest that fewer young men were becoming stone masons, and that not many of the sons of an older generation of stone masons were following the same trade as their fathers. It also indicates that many masons lived long lives.

The overall pattern of emigration to Upper Canada was given by Helen Cowan (1961) in her book British Emigration to British North America. Among emigrants arriving at Quebec during the years 1846-1859, "Bricklayers and masons" increased to a maximum of 228 in 1854, "miners" to a maximum of 238 that year, and "Stone-cutters" to a maximum of 67 that same year.

Much the same trends were also shown on a larger scale by farmers and labourers, so this trend may just reflect the overall growth in Ontario's economy (and its decline after 1857), rather than a particular demand for workers in the quarrying and building trades.

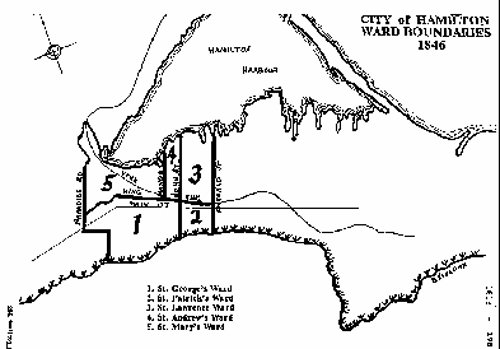

At that time, the city of Hamilton was divided into four Wards, shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: City of Hamilton Wards (they remained in effect for the next 25 years).

Most of the Quarrymen lived in St.Patrick's Ward, south of King, between John and Emerald Street (a region often referred to later as "Corktown") but among stone workers living there, the English and the Scottish were more common there than the Irish). In those days, the streets running east west were from the south to the north:

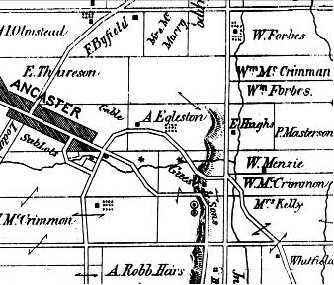

These streets are shown in Figure 3, which also shows how close they were to the main Mountain access roads.

Figure 3. Part of an 1878 map of Hamilton, showing road names. The Church of the Ascension is also shown.

At the south end of Wellington Street, Hannah Street was the closest to the Mountain: so was one of the closest streets to the quarries. Concession Street ran east west above the edge of the Mountain (or below it further to the west).

The main roads up the Mountain have been listed in Mountain Memories (Hamilton Mountain Heritage Society, 2000); they were James Street (1805), connecting to the Caledonia road (now Upper James Street, Highway #6), which was improved with stone, beginning in the 1840s) and Gage avenue (known originally as "the stone road").

Access between the town and the mountain was improved substantially after the construction of the "Jolley Cut" in 1870: it was the first road free from tolls to connect the town with the Mountain above. Beckett's Drive was not constructed until 1894.

The 1853 City Directory list two inns: the Mason's Arms, 32 Upper John; and the Stone Cutters' Arms Inn, 34 Upper James. In those days "upper" did not mean on the Mountain, but south of King St. Working in quarries was thirsty work - but the two inns are not listed in later Hamilton directories.

In the early 1800s, labourer's wages were about 50 cents per day; the work was hard manual labour, and working conditions were appalling. Even skilled stone masons were only paid about three times as much. In contrast, the military working on the Rideau canal received not only their normal wages, but one hundred acres of land after the work was completed (Legget, 1972, Rideau Waterway, p.47).

Two thousand or more emigrants, many of them Irish, also worked on the Rideau canal, and many later settled along the route.

For comparison, Woodhouse in his history of Dundas gave the following figures at the time of Gourlay's 1817 questionnaire: labourers were paid about $6-20 per month, or roughly 20-60 cents per day; carpenters and mason earned $40 per month, or roughly $1.50 per day; stone was sold for $2.50 per (cubic) toise, about 8 cubic metres, sufficient to built a wall 0.5 m thick, 2 m high and 8 m long.

In 1827, William Hardy wrote "I am at Hamilton, in the District of Gore, building a new cut-stone Gaol and Court House [now demolished, but very probably built from Whirlpool sandstone]...I give Masons [$1.5] per day and Labourers [$0.75] per day..." (MacRae and Adamson, 1983, Cornerstones of Order: Courthouses and Town Halls of Ontario, 1784-1914, p.52).

How do these figures compare with modern wages? A labourer in Ontario earns a minimum wage of $10.25 per hour ($70-80 per day) and a stonemason about $25 per hour: so it would seem that, though the wages have increased by a factor of 100, the status of a stonemason has remained about the same or even decreased somewhat in modern times.

Both the cost and quality of living were much lower then than now. For example, houses had no plumbing, only one or two wood-burning fireplaces or stoves, and of course no telephones or electricity. Taxes were low, but the government paid for almost no services (very few roads, little if any education, no medical expenses, and only minimal policing).

A stone house that cost $1000 to build in the mid-nineteenth century might well cost $300,000 now (not including the cost of the land), but at least part of that cost can be accounted for by added conveniences.

Very little is known about who the masons were, except their names. A few achieved fame, but mainly because of other activities. For example, the Scotsman Hugh Miller originally a stone mason, became a self educated geologist, and a best-selling author. He was also one of the writers who supported the Presbyterian Free Church movement Disruption - and was opposed to the Scottish emigrating to the colonies!

Figure 4. Part of a painting showing the Disruption of 1843: Hugh Miller is shown taking notes on the right.

Among fictional lives of stone masons, perhaps the best known is found in Thomas Hardy's Jude the Obscure - a gloomy portrayal of a man struggling for advancement through self-education.

The lives of stone masons were more happily celebrated by the American poet Robinson Jeffers, who constructed his own stone house, Tor House, in California, and wrote a famous poem To the Stone Cutters.

The following are some local quarry men and masons, about whom we know more than just their names (the information is partly from the Hamilton Dictionary of Biography).

George Fred Webb was 16 years old at the time of the 1881 census. He was born in England, son of John Webb (1843-1892) also described as a "stone mason", also born in England. George was an Anglican, who worked on St. John's Presbyterian Church in 1890.

He owned two quarries: the one below The Jolley Cut, and another in Barton (on the Mountain) near the reservoir (so probably near Upper Ottawa Street). This quarry was described by Goudge (1938, Canada Department of Mines and Resources, Mines Branch Report 781, p.304) as the Webb Quarry: it exposed formation from the Ancaster Chert Beds down to the Reynales.

It is not clear what use was made of the stone. For good quality stone from the Gasport, it is necessary to go further east, at least as far as Beamsville, though a few buildings in western Ancaster (notably The Hermitage) were also built from local Gasport.

Donald Nicholson, was born in Scotland in 1827. He was listed in the 1851 census (living in St. Lawrence Ward), and in the 1853 city directory, where he was described as a stone cutter. By the 1860s he was described in the directories as either a contractor or a builder (living on Bold St), and in the 1871 Census he was listed as a "contractor," 44 years old, living in St Georges Ward.

He worked on terrace houses including the famous Sandyford Place. He was about 30 years old when the terraces were built. He may have been the builder, rather than the stone mason. He was elected three times as Alderman of St. George's Ward, and died in 1876.

Robert McElroy (ca 1810-1881) was born in Ireland. He was a contractor who lived in a stone house on Mohawk Road near Upper James, built for him as a wedding present by his father in law, Peter Hess. He owned a quarry on the mountain, but it is not clear whether or not it produced building stone. He served as Mayor of Hamilton from 1862 to 1864.

Samuel Lawrence (1879-1902) was a stonecutter, born in Somerset, England, son of a stonecutter. He came to Hamilton in 1912, and immediately joined the Journeymen Stonecutters' Association of North America, and became active in union affairs. He gave up working in quarries after he was elected to the Hamilton Board of Control in 1928. He served as Mayor from 1946-1949.

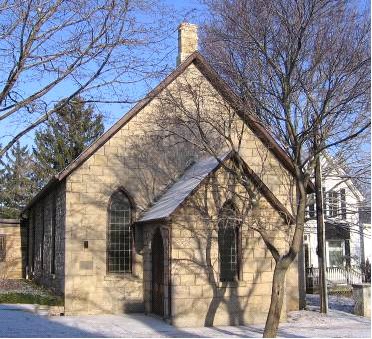

George Guest (1810-1878) was a stonemason, who came from England in 1855 and built the Bethesda Church, and New Zion chapel (the first Ryerson Church). George Guest had a son Edgar (1848-1901) and a grandson, Edgar James (1872-1914) who carried on the family business. Another son, George Jr., became a blacksmith and wagon maker (Hamilton Directory, 1868; census 1871).

F. Postans (in Ancaster's Heritage, p.70) wrote that New Zion was built in 1869 from stone supplied by Guest gratis. The map of Ancaster in the Historical Atlas of the County of Wentworth, Ont. (Page and Smith, 1875) shows the property owned by "Guest & Sons:" it is in Concession 2, lots 46 and 47, on both sides of Wilson Street above and below the crest of the escarpment (two lime kilns are also shown at the crest just east of Wilson St).

Figure 5: Part of the 1875 map of Ancaster: note that north is to the right. It was the Egleston family that built the Old Mill. Lime kilns are shown by a circle enclosing a dot.

The LACAC report on Ancaster buildings noted that in England Guest had specialized in stone carving, but found there was no market for such work in Canada, so he became a quarryman and lime burner as well as a mason. Perhaps he made the carvings seen in St. John's Church, which seem to be the only stone carvings in Ancaster.

Figure 6: The New Zion chapel in Ancaster, built of Eramosa dolomite donated by George Guest from his quarry.

James Phillipo (1794-1850) built the Phillipo house in Ancaster and left it to his son John Phillipo (1838-1912). John was not a mason, he was listed in the 1865 and 1867 Hamilton Directories as a "teamster" living in Ancaster, and he sold his father's house in 1851 (when he was only 13) for £42.10, to Adam Marr, a cabinet maker (McBurney and Byers, Homesteads: Early Buildings and Families from Kingston to Toronto, 1979, p.148).

The 1875 map shows a Phillipo owning property in lots 41 to 43: this was probably purchased by James and inherited by John. Another Phillipo (son?), Charles, was twenty years older, and leased the Union Hotel in 1865, but was no longer proprietor in 1874. In the 1871 Census John Phillipo is described as a labourer; Ancaster's Heritage (v.1, p.75) also describes him as the village constable. In the Hamilton Directories for 1871 and 1874 both Charles and John are listed as Phillips, rather than Phillipo.

Figure 7: The Phillipo House, Ancaster, built in the 1840s from local dolomite rubble.

Peter Middleton (1841-?) was Scottish, and his son John was born in Scotland in 1868. They came to Canada in the 1870s. He was listed as a "traveller" in the 1875 Directory, living on the stone road in Ancaster, but the 1881 Census listed him as a stone mason. He was deputy reeve in 1888-1889.

He had two sons, both of whom became stone masons. The elder son, John M. Middleton (1868-1953), was mentioned in Ancaster's Heritage (v.1, p.76), and the younger was Peter M., born in 1880, who lived all his life in Ancaster.

The stone house on Golf Links Road was built in the late 19th century using Eramosa dolomite from a quarry operated in Ancaster by the Middleton family. The Middleton quarry was described by Willet G. Miller (1904, Limestones of Ontario. Ontario Bureau of Mines Report, v.13, pt.2, p.125).

About five feet below the top of the quarry was "a heavy limestone...somewhat shattered...by jointing, but still furnishing large quantities of excellent building stone," and below this were a further 13 feet of "limestone"(the stone was certainly dolomite not limestone). Miller (1867-1925) was appointed in 1893 to head the first School of Mining at Queen's University, and in 1902 as Ontario's first Provincial Geologist.

By pinz (anonymous) | Posted August 31, 2011 at 23:44:20

Great research/story - any idea who built Hamilton's 'Eco-House'?

By TnT (registered) | Posted September 01, 2011 at 00:37:47

What is meant by shale? Is it a type if stone, or a formation style?

By TB (registered) - website | Posted September 01, 2011 at 07:24:52

Thank you very much Mr. Middleton, I've thoroughly enjoyed each of your articles. Do you know what craftsmen fashioned the slate roofs seen on many buildings around Hamilton and where their materials came from?

Comment edited by TB on 2011-09-01 07:26:45

By GerryM (registered) | Posted September 01, 2011 at 08:46:45

The "Eco-House" also known as the Veever's House was built in 1856 using Whirlpool sandstone quarried nearby from the base of the escarpment. Its history is well described by Shaw and Crankshaw in their book Heritage Treasures.

Shale is just hardened, fissile mud -- no good for building. When heated by deep burial in the earth it becomes slate. I am not sure where the slate used in roofs in Ontario came from: probably Quebec or Vermont.

Comment edited by GerryM on 2011-09-01 08:47:31

By TnT (registered) | Posted September 02, 2011 at 13:50:00

In many countries mud is baked into brick forms and made into houses while still wet. Sun baked mud I guess, what is the life span of these properties?

By TnT (registered) | Posted September 04, 2011 at 09:01:04

I have a picture of the corner of a new building, is the material actually stone and work done by new stone masons, or is it some kind of concrete imitation? http://www.flickr.com/photos/tntlockandk...

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?