With asset leverage able to surpass 250 times the nominal value of an underlying security, the ballooning of paper assets due to the Nuclear Renaissance can quite quickly make the US subprime asset balloon seem rather small beer.

By Andrew McKillop

Published November 04, 2010

The coming nuclear financial disaster in fact has many previous models. These stretch back to "classic" stock exchange panics and asset inflation surges of the 19th and 20th centuries, and to the first nuclear asset boom of about 1974-1983. In particular, the US subprime crisis will provide a model by it size, economic damage and international impact.

This crisis was inevitable by the years 2005-2006, occurred in 2007 and caused massive financial and then economic collateral damage in 2008 and 2009. This damage continues in 2010, notably due to the crisis' impact on public sovereign debt of the most affected states.

The subprime crisis will go on affecting the integrity of banks, other mortgage lenders, insurers and both financial and state actors - including central banks and monetary authorities - in the US, Europe and globally, for several years. This is because this crisis was large, a supposed surprise, and essentially offloaded the private debt of failed financial players" to the public debt of governments which bailed them out.

The subprime crisis' impact on the bank-finance-insurance sector was very impressive. While opinions differ on the date the crisis started in 2007, by late 2008 it was still driving very large write-downs in nominal asset values. As Bloomberg reported on August 12, 2008:

Banks' losses from the U.S. subprime crisis and the ensuing credit crunch crossed the $500 billion mark as writedowns spread to more asset types.

The writedowns and credit losses at more than 100 of the world's biggest banks and securities firms rose after UBS of Switzerland reported second-quarter earnings today, which included $6 billion of charges on subprime-related assets.

The IMF in an April report estimated banks' losses at $510 billion, about half its forecast of $1 trillion for all companies. Predictions have crept up since then, with New York University economist Nouriel Roubini predicting losses to reach $2 trillion.

"It just keeps spreading from one asset to another, so it's hard to know when these writedowns will stop," said an analyst at KBC Financial in London. "The U.S. economy needs to stabilize first. But even then, Europe could lag and recover later. There's still a lot more downside."

Outside the USA, the impact of the crisis - first on the bank-finance-insurance sectors, then on the public finances of most OECD countries - was also radical. Response by political leaderships to the finance sector crisis was supposedly "Keynesian".

The process of saving the economy by handing over or injecting a total of perhaps $3.5 to $4 trillion through 2007-2010 into the bank-finance-insurance sector in the OECD countries is Keynesian in one sense: national debts and government budget deficits have radically increased.

Several EU27 states including East European members, Greece, Spain, the UK, France, Portugal, Ireland as well as the USA have seen their public national debt grow so fast that their public finances are now structurally unsound. If economic growth does not return soon, and continue for several years, the unthinkable prospect of central bank failure will return.

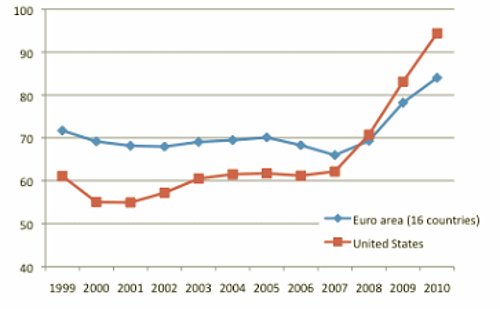

We can note that the approximate $4 trillion of 'Keynesian bailouts' in the OECD countries, since late 2008, is equivalent to about 6.5% of world total GDP in 2008 (using IMF data). Debt growth of states triggered by this crisis is shown below:

Government consolidated debt as Percentage of GDP (Sources: European Commission, AMECO)

The mechanism of the coming nuclear asset boom-bust, or nuclear financial crisis, is easy to describe: investment in productive assets, such as housing or nuclear power plants, becomes a conservative inflation hedge as well as a productive asset, before finally "mutating" into a purely speculative gaming chip or token.

During this process, the inflation rate of asset prices, and related or supporting assets (for example housebuilding materials for realty, and uranium for reactors), increases very fast. Towards the end of the process, the inflation rate is extreme.

The time needed for the shift from one category to the next can be limited - only a few years as in the US and European "railroad booms and slumps" of 1873 and 1893, or the "copper panics" of 1893 and 1907. In these "classic crises", the borderline between rational investment in productive assets (railroads and copper mines), and an inflation hedge, and finally an outright speculative play, was compressed into a period of as little as 3 to 5 years.

During this critical mutation period, as in any financial crisis, public authorities and so-called experts will reassure speculators the underlying assets are sound and even "undervalued" when marked to market.

With nuclear assets, starting with reactor construction costs, we have rapidly rising inflation since about 2005, the approximate date for the start of the so-called Nuclear Renaissance, or the new boom in nuclear power with extreme high forecasts of new reactor orders, building, and operation through 2010-2020.

These projects, if they are completed, will be mostly in Emerging Economy countries - not in the "old nuclear" nations of the OECD group - and this will obviously include increased sovereign debt, and increased involvement by the IMF and World Bank, and UN agencies such as the IAEA.

Reactor building costs and forecasts, since about 2005, have radically increased, with the current annual inflation rate probably how standing at about 25 percent.

In a 2010 report published by the University of Vermont Law School on reactor costs and nuclear economics, its author Dr. Mark Cooper said:

We are literally seeing nuclear reactor history repeat itself. The ‘Great Bandwagon Market’ (of the) 1970s and 1980s was driven by advocates who confused hope and hype with reality. .... in the few short years since the so-called ‘Nuclear Renaissance’ began there has been a four-fold increase in projected costs. In both time periods, the original low-ball estimates were promotional, not practical; they were based on hope and hype intended to promote the industry.

The previous nuclear asset boom of about 1974-1983 was essentially driven by the confused and inaccurate belief among OECD leaders and so-called experts that Nuclear power saves oil, protecting or shielding the economy and its productive assets from oil price inflation caused by the Oil Shocks of the 1970s.

The imagined rate of inflation of oil prices (which in fact started declining by 1983 and collapsed in 1986) was utilised to inflate the Net Present Value (NPV) of nuclear assets, entraining a rapid increase of inflation inside the nuclear sector.

By October 1975, for example, Westinghouse of the US was forced to declare force majeure on supplies of uranium for the large numbers of reactors it was building at the time, due to fast rising uranium prices.

These in fact continued rising in price, by about 200 percent through 1974-1977.

The mechanism tends to activate faster when or if other inflation-raising factors are in play. For the US subprime crisis, these factors were very powerful.

They firstly concerned the "securitization" of financial assets through so-called financial engineering, starting about 1995 and intensified by deregulation and offshoring and vastly bigger extended asset spaces.

The process was secondly intensified by the massive inflation of house prices in the US and Europe, especially through 2000-2005. The first of these, "securitization", enabled vast and opaque financial balloons to be created on the back of tiny, or small real assets, while spreading the inherent dangers and risks of that asset, like a virus, to the rest of the pile of gaming chips.

For the US subprime crisis, the inflation generated by this process fed back into housebuilding labour and materials prices, and potentialized the subprime crisis. The crisis was then activated by falling economic growth, rising interest rates, lower disposable incomes due to rising food and oil prices, loss of investor confidence, and of course several other factors, especially the massive overpricing of the underlying asset, that is houses, during the asset ballooning process.

It is imagined by public opinion and reinforced by government friendly media, and communicated by political leaders, that nuclear power is a strong productive economic asset. The powerful but no-longer-exclusive roles of the state in nuclear power decision making and in nuclear financing (through subsidies and all other possible forms of government hand outs) is imagined to guarantee probity.

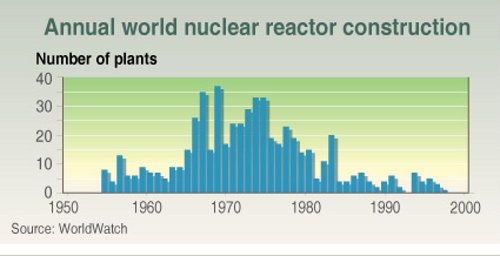

In fact, we find the first boom of civil nuclear power, of around 1970-1983, was in major part driven by irrational but government initiated belief that nuclear power is an "inflation hedge" against high oil prices.

Source: Grida, Norway and WorldWatch (not corrected for average MW size per reactor completion)

In the 1970s, OECD governments were so alarmed at oil price rises and the one-time oil supply cutoff of 1973-1974 that OECD institutions and agencies such as the recently created IEA, and existing entities like the UN IAEA, World Bank and others quickly generated the myth that nuclear power is a 'silver bullet' inflation hedge.

Massive development of nuclear power was imagined as able to protect both state and private sector economic assets from inflation due to oil. In NPV terms, this caused a clear break between the role of nuclear power as an economic productive asset and nuclear power as an inflation hedge.

Simple energy economics show that nuclear power saves very little oil, but the political and economic myth that 'Nuclear Power Saves Oil' was firmly entrenched in the political reasoning and energy policies of major OECD oil importer governments by 1975.

The rationality of the then-new hope that atomic energy will protect and shield us from oil price inflation can be compared with the rationality of any other asset ballooning process, such as the 1907 Copper Panic, and of course the 2007 US Subprime Crisis, or the 1929 and 1987 stock market crises.

Due to this oil inflation hedging role, the NPV of nuclear financial assets could be talked up to new extremes only limited by the imagination of so-called 'experts' on the rate of price increases applying to oil going forward. Very similar irrational ballooning of NPVs were aplied to some Green Energy assets during the period of about 2005-2008, on the basis that these assets will "protect us" from dangerous climate change, and rising oil prices.

Because oil prices had risen about 300 percent in 1973-1974, and about 120 percent in 1979-1981, nuclear NPVs in that period could be increased by massive amounts, and even by triple-digit rates. With no surprise at all, this quickly fed back as fast rising reactor construction costs, nuclear sector raw materials prices, and uranium prices for nuclear reactors.

Another proof by the negative of the linkage with imagined or predicted oil price inflation rates, is how fast reactor orders and completions declined as oil prices fell from their 1980 peak, in the years 1983-1986.

The effective collapse of oil prices in 1985-1986 was in fact at least as decisive in imploding the nuclear asset balloon, as the Chernobyl disaster of 1986, which was a veritable coup de grace for the marketing image of 'clean, safe and cheap' electric power!

With cheap oil restored for a long but provisional interval (1986-2000), oil importer governments of the OECD group quickly ceased to see the previously clear "inflation hedge" role for nuclear power.

So-called experts who had helped to talk up the nuclear asset balloon fell silent, and turned to other sectors of interest, such as lauding the benefits of "free trade" in the energy sector, helping generate the Enron scam.

The implosion of the nuclear asset bubble at the end of the 1974-1983 boom quickly shrunk nuclear NPVs, led to near bankruptcies and forced mergers across the reactor industry, loss of jobs and productive assets, and major negative impacts on downstream linked nuclear business sectors.

With much cheaper oil, and very cheap natural gas and energy coal, the alternatives to nuclear power generation and its very high capital costs were abundant in the 1985-2000 period.

In commercial terms, this was the nuclear winter for atomic power.

Today, the states of the OECD with the largest nuclear industries, notably USA, France, Japan, South Korea, Germany, UK (with fast rising competition from state-backed entities in China and India) have serious or massive national debt and public spending deficit crises to manage, one way or another.

Unlike the previous boom period, th search for new export markets for "big ticket" items like weapons, aerospace, telecoms, high speed trains - or nuclear power - is now more than just an attractive new initiative, but a critical strategy.

Today also, so-called financial engineering, which was strictly in its infancy in the late 1980s and early 1990s,, has itself ballooned despite the blowback from the 2007-2009 crisis.

The finance sector has been richly bailed out at public expense, and at most is only slightly more regulated than before the subprime crisis. Its capability, and "basic instinct" to inflate assets wherever possible, until they implode, are surely as strong as ever.

Combining the need for OECD government to find ways to reduce, displace in time, or dishonor their debts, continuing fear of high oil prices, and the remaining (but now weak) posturing by some OECD leaders on the need to "fight" climate change and develop low carbon energy, the likelihood of a nuclear asset boom is very high and increasing every day.

Depreciating major currencies in the so-called "currency war" (formerly called competitive devaluation), itself a spinoff from the debt crisis, will lead to rising commodity prices and especially oil prices.

Key high technology metals needed for reactor building will of course rise in price as well, raising the economic inflation rate affecting the nuclear sector, while higher oil prices will feed back as renewed belief in the founding nuclear myth that "nuclear power saves oil".

We are therefore already at the stage where a purely economic productive asset (reactors) becomes an inflation hedge and inflation generator, before terminating as a financial gambling chip or token, which will be followed by the implosion of the asset bubble.

Write-downs and losses of nominal value, we can note, can be 99% (ie. "penny on the dollar"). Bankruptcies, forced mergers, job losses and wasted resources on a massive scale will be tiresomely classic, and supposedly unavoidable.

Due to the intrinsic and inherent technological, radiological and industrial dangers of nuclear power, asset implosion in this sector carries high risks.

However, unlike the US subprime crisis, which started as a domestic economy crisis, the nuclear boom-slump of 2010-2020 will be played out across the world from the start. What is called securitization is now a cornerstone of the global economy and a massive financial industry, and has a very large outlet in the asset space of government debt, currencies and interest rates - all of which will play (and are already playing) in the nuclear asset growth process.

Leaders of countries with large national interests in the nuclear sector, and high or extreme national debts and/or budget deficits such as the USA, France, Germany, Japan and UK are actively seeking "new financing facilities" for nuclear power expansion worldwide.

This notably includes prposals by leading politicians for IMF action to create and issue new amounts of SDRs "ab initio" for a 'Nuclear Fund' similar to the mooted, and failed 'Green Energy Fund', or facility, finally rejected by an IMF full board meeting in March 2010.

Other initiatives will include increased technical support (and possibly a financial role) from and for the UN IAEA and related agencies and institutions like the OECD NEA.

The private financial sector, from commercial banks, private investment banks and hedge funds to a wide range of other players is now very active in nuclear financing, and this activity will soon increase very fast.

The "players" in this asset levering or bubble-making process will essentially bet on the likelihood or not of a nuclear borrower defaulting on all kinds and classes of debt, linked to reactor building and uranium supply contracts, power transmission development contracts, energy intense industrial project contracts, downstream development contracts for offices, hotels, and commercial construction - and so on.

With asset leverage able to surpass 250 times the nominal value of an underlying security - a 900 MW nuclear reactor costing US $6 billion, for example - the ballooning of paper assets due to the Nuclear Renaissance can quite quickly make the US subprime asset balloon seem rather small beer.

In particular the process will draw in sovereign borrowers. These will especially include the many "candidate countries" of the South who now want to accede to the atom, in a context where the nearly 20-year-long debt crisis of the Third World has been reversed - with the OECD North now wallowing in unpayable debt.

Since the ex-Third World, or Emerging Economies are now mostly solvent, sometimes with comfortable trade surpluses, and often have high rates of economic growth (2 to 5 times faster than OECD countries), it is logical to OECD strategists that nuclear debt can be utilised to siphon off some of their new wealth, and perhaps "restore" them to the status of debtor nations.

In many cases among the candidate new nuclear nations, for example Ghana, Indonesia, Sudan, Bangladesh, Algeria, Kazakhstan, Mongolia their national integrity and stability, as well as humdrum basics like their power transmission and distribution systems, are unsure or weak, and their economic ability to pay back nuclear loans and charges over 30 to 50 years is intrinsically high risk.

This risk is no bigger than the case of the US subprime crisis, where the bet can be summarized as wagering if low income home buyers provided with huge loans at so-called "variable" rates - that is rising rates of interest - will default.

The question was not "if", but "when", to the supposed surprise of the financial players involved and to the political leaders governing the economy.

The nuclear asset boom will very surely include plays on national debt, currencies and interest rates, that is "securitization", generating ever larger financial vehicles which supposedly "spread risk". By this mechanism, nuclear financial risks will be both massively increased, and spread across the world, helping explain the probable early involvement of the IMF.

Typical loan arrangements, already utilized in the example of the KEPCO 4-reactor project in Abu Dhabi, will be syndicated loan arrangements with linked credit default, currency and interest rate swaps. They will also increasingly generate SIVs (structured investment vehicles), which can have nominal values that easily exceed 200 times the loan amount actually needed for buying the "underlying asset" of the reactor and its initial load of uranium fuels.

Government debt will quite rapidly be "packaged" into nuclear financing SIVs or other vehicles and facilities.

Unsurprisingly, positive feedback is already acting in the shape of fast rising inflation in the nuclear sector, and this inflation will grow until the nuclear asset mutates into a simple betting chip. At this final stage, it will still be called a "security" but is essentially doomed to total loss on the financial casino gaming tables of the world.

Until almost that stage, nuclear assets will still be sold to unaware financial players as an asset that may be speculative but which of course has massive upside potential.

Nuclear power will continue to be sold to governments and public opinion as a form of energy security, protecting them from oil price inflation, as a helping hand in the heroic struggle against climate change, and of course a supplier of clean, cheap and safe electric power.

Cost inflation in the nuclear industry is now running at about 25 percent a year, and the explanation offered for this by the nuclear industry is "rising raw material costs", and sometimes "more sophisticated designs", for example safety features, ability to resist wide-body airplane crashes (in the case of French EPRs), more efficient utilisation of uranium, reduced cooling water needs, and so on.

This can be contrasted with industry marketing claims of falling unit costs due to bigger reactors, so-called modular design, industry standardized components - and enthusiastic support from the financial industry supposedly driving down the price of loans for nuclear power projects.

We are therefore at the stage of the asset ballooning process where we have had a first doubling or tripling of in-sector inflation rates (doubling or tripling of reactor construction costs 2007-2010), but it is almost certain this crisis will attain very large nominal values, before it implodes.

By "very large" we could suggest as much as 200 times the value of the underlying assets - notably reactors, fuels, services - generated by the Nuclear Renaissance through 2010-2020, if it lasts that long.

Nominal values could likely attain US$ 200 000 billion ($ 200 trillion), equal to more 3 years of world total GDP using IMF estimates for world GDP.

Implosion of this asset bubble will therefore be a lot more menacing for national finances of all player governments than the implosion of the US subprime asset bubble - which itself radically increased the national public or sovereign debts of nearly all OECD countries, and has led to "currency wars" of competitive currency devaluation ever since.

For these reasons, over and above the environmental, industrial and technology issues, radiation pollution, weapons proliferation (including DU weapons and Dirty Bombs), and so on, the true size of the risks of nuclear financial disaster should be taken seriously, discussed, and acted on.

By Ty Webb (anonymous) | Posted November 04, 2010 at 13:26:25

Wow, this has a lot to do with Hamilton!

By Carbonera (anonymous) | Posted November 04, 2010 at 15:06:56

Andrew, I'm starting to think that you may be a lobbyist for the coal industry.

By Mr. Meister (anonymous) | Posted November 04, 2010 at 16:21:46

Loooooooonnnnnnng read. Still not sure how you can relate the subprime crisis, (lending money to people who do not qualify for a loan)relates to building to many reactors leading to a shortage of nuclear and construction materials and a jump in their prices. At least that is what I think the novel was trying to tell us.

More gloom and doom. We are all going to be stranded (no oil to power our cars) in the sweltering (global warming) suburbs while we starve (over population and lack of food production and get fried by the sun (hole in the ozone layer.)

Remind me to only invest in sun block, electric cars, alternative energy and high tech food production.

By Undustrial (registered) - website | Posted November 04, 2010 at 19:50:04

Nuclear power has always been, in many ways, more of a financial construction than a practical technology. It's a great way to toss money around, since the whole process is so expensive and inefficient, but the power gained for inputs is rarely worth it. There are too many costs which simply don't show up on balance sheets - nuclear power is legally exempt from insurance laws, and nobody knows what the eventual cost of fully decommissioning reactors (never been done) or sustainably disposing of waste (none of Ontario's waste has even left the reactor sites - most now sits in sheds). And then there's the mining issues. And then there's the weapons proliferation issues. And then, of course, there's the enormous government subsidies still needed, decades later, to keep the whole thing afloat.

And as for Hamilton - cities like us (rapidly de-industrializing) need some global perspective here, and this article makes some very important points.

By bobinnes (registered) - website | Posted November 04, 2010 at 20:52:04

Undustrial, your urgent concerns seem lost on the first three stooges, who no doubt, are quite representative of the mentality of many.

I am surprised at the assertion that nuclear does not save oil - meaning I assume, oil equivalent energy, ie. coal also. This link seems to suggest otherwise though to be sure, I haven't done the math. Can anyone comment on this important aspect?

By mrjanitor (registered) | Posted November 04, 2010 at 21:24:49

I was reading in The Toronto Star today that the Bruce re-build was already 2 Billion over cost estimates, what that estimate was they didn't say. The maintenance costs on these reactors is unmanageable.

By Undustrial (registered) - website | Posted November 05, 2010 at 11:09:03

I am surprised at the assertion that nuclear does not save oil - meaning I assume, oil equivalent energy, ie. coal also. This link seems to suggest otherwise though to be sure, I haven't done the math. Can anyone comment on this important aspect?

It's kinda like the tar sands...and that's why I try to avoid using statements like that. It can, and in many cases does, use more energy (usually petrochemical) to mine, refine, enrich and use uranium (or bitumen) than it generates, but not always. For that reason, we face a "peak uranium" crisis much like oil, where we will have tons of it left, but not in concentrations that are worth digging up.

By Tartan Triton (anonymous) | Posted November 06, 2010 at 09:36:14

I read that fast and was worried that the Great Lakes were going to be used as a nuclear submarine route. Phew!

By Mr. Meister (anonymous) | Posted November 08, 2010 at 11:48:46

And in the meantime nuclear reactors keep people warm, cooks their food and keeps their tools going. At the lowest price per KWH their is.

By Kiely (registered) | Posted November 08, 2010 at 15:32:26

For that reason, we face a "peak uranium" crisis much like oil, where we will have tons of it left, but not in concentrations that are worth digging up. - Undustrial

Keep in mind most mines rarely dig up one thing. Uranium is often found in copper mines.

I know two very rich copper mines, one in Zambia and one in China, that are sitting on their secondary Uranium reserves, apparently waiting for the market price to increase. The hole in the ground is often being dug anyway so it becomes hard to crunch numbers to find the actual cost of uranium extraction... processing is of course a different matter.

By Undustrial (registered) - website | Posted November 09, 2010 at 17:02:29

Canada has plenty of dedicated uranium mines, and a good many are idle and have been for ages, due to low prices and having mined out the best ore. I have lots of family and friends around Elliot Lake, for instance. Kinda hard to believe that the price of raw uranium has been in the dollars-per-pound for decades, until the last few years. Compare that with what a few pounds of ENRICHED uranium is worth, and you'll see the issues with processing costs...

Oh, and it's now around $50. When oil spiked, it took a very similar jump up toward $140. Clearly, we can't rely on $10/lb uranium in a post-oil era.

By Kiely (registered) | Posted November 11, 2010 at 15:37:21

Clearly, we can't rely on $10/lb uranium in a post-oil era. - Undustrial

I hope we never have to... it's certainly not my preferred form of energy.

By bobinnes (registered) - website | Posted November 25, 2010 at 13:50:29

I'm just listening to CBC Dispatches podcast on thorium. Promising technology, costly conversion, a 3300 ton US dumpsite could power US electric grid for 2 years. Liquid thorium reactors very safe. Downside, no plutonium (weapons?). India, Brazil, Japs, Russians looking at thorium reactors.

This is all new to me so if anyone knows anything would be interested to hear.

By Pxtl (registered) - website | Posted November 25, 2010 at 16:05:50

@Undustrial

Isn't the whole selling-point of the CANDU system that, while it requires a large amount of heavy (deuterium) water, it runs using non-enriched uranium (the natural mixture of U-235 and U-238)?

By OrelsDem (anonymous) | Posted April 20, 2014 at 03:28:46

No matter which way you end up paying for your almost no risk to blow your budget because of unexpectedly high expenses. The best format to get your articles base with well written articles that incorporate primary keywords, the more traffic and exposure you will be able to generate. The first time you log in after signing per click advertising which will bring you traffic very quickly. buy web traffic

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?