In 1990, Canadians paid $155 million to terrorize Mohawk men, women and children defending their unceded land and protecting their sacred burial ground from development. Their land claim remains unresolved to this day.

By Doreen Nicoll

Published September 25, 2019

Pascal Quevillon, Mayor of Oka, Quebec was in the news in July for making racist statements and inciting violence against the residents of Kanesatake, a Mohawk reserve.

He was upset with the reconciliation efforts of local developer Gregoire Gollin to transfer 60 hectares of disputed land back to its rightful guardians, the Mohawk community. The transfer was to take place through the federal government's Ecological Gifts Program. Gollin had also offered to sell another 150 hectares of land to the Mohawk Nation.

In August, at a summit of First Nations leaders and mayors, Quevillon apologized to Kanesatake Grand Chief Serge Simon. But to date there's been no decision regarding returning the land known as the Pines back to the people of Kanesatake.

The land in question was never ceded, it was stolen from the Mohawk Nation in the early 1700s by the French monarchy and Catholic Church.

Most Canadians won't recognize the name Kanesatake, but it was the focus of a military siege in 1990 most settlers mistakenly refer to as the 'Oka crisis.'

This is extremely egregious, because at no time were residents of Oka, a small village northwest of Montreal, in danger. The village, best known for a semi-soft cheese made by Trappist monks, was in fact home to the violent aggressors. It's a stance the current mayor has once again threatened to take in order to disrupt Gollin's act of reconciliation.

The proposed expansion of a local nine-hole private golf course originally built on expropriated Kaniew'kehaka (Mohawk) lands, along with approval for a luxury housing development on expropriated Mohawk lands that contained a sacred burial ground, led to the 78-day armed standoff between Mohawk land protectors, Oka residents, Quebec police and the Canadian army.

On July 11, 1990, Kanesatake residents blocked the road through the reserve. Then, in a show of support, residents of the Kahnawake reserve blocked the Mercier Bridge connecting LaSalle on the Island of Montreal with the Mohawk reserve and the suburb of Châteauguay on the south shore of the Saint Lawrence River.

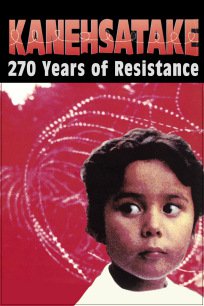

That's when Abenaki filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin began filming the entire standoff from behind Mohawk lines. The result was her 1993 documentary, Kanesatake: 270 Years of Resistance.

Obomsawin's film also documented the silencing of mainstream journalists while various levels of government controlled what little misinformation the general settler population had access to. Obomsawin's film is the only factual account of the entire crisis from beginning to end. Here are highlights of the misuse of power Obomsawin's camera captured.

Swat teams descended upon Kanesatake firing tear gas to disperse Mohawk residents. When that failed to move the protestors, members of the swat team began firing bullets. In the end one officer was dead by what was purported to be friendly fire that possibly ricocheted off a tree or bush. In response, Premier Robert Bourassa dispatched 1,000 police officers to Oka home to a mere 1,800 residents.

In an interesting turn of events, the residents of Chateauguay overwhelmingly came out in support of Mohawks living in Kahnawake and Kanesatake.

Only John Ciaccia, Provincial Minister of Indian Affairs, acknowledged Mohawk land had been taken without consultation or compensation for the original nine-hole golf course. All other politicians chose to ignore this fact.

When food for the Mohawk protectors was severely restricted, Ciaccia put an end to that - although he could not prevent the army from damaging supplies while inspecting for 'suspected weapons' that never materialized.

Tom Siddon, Federal Minister of Indian Affairs, established negotiations between the Province and Mohawk representatives. But three days later, 2,600 Canadian armed forces troops were deployed to the area.

Negotiations continued at the Trappist Monastery considered neutral territory by all sides. Despite the fact that the federal, provincial and Mohawk governments were able to agree on 13 of 15 issues, seven days later negotiations broke down when an agreement could not be reached ensuring Mohawk sovereignty and amnesty for all activists.

As international support for the Mohawk Nation grew, the army invaded Kanesatake. Obomsawin filmed a convoy of cars filled with the elderly, women and children leaving the reserve. The vehicles were summarily attacked by settlers from Oka who pummelled the convoy with large rocks. Several people fleeing the occupied reserve were injured and a Mohawk elder later died of a heart attack.

A remaining 100 Mohawk women, children and men took shelter in a treatment centre. The media was told to leave, but 12 journalists made it to the treatment centre encampment and hunkered down to cover the next phase of the standoff. At this point journalists could only get information out by phone and the information Canadians were being fed was being manipulated by those in power.

Throughout the siege of Kanesatake, police, military personnel and politicians at all levels, including Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, treated journalists as if they were enemies of the state.

On September 26, the remaining 30 warriors, one spiritual leader, one traditional chief, 19 women and seven children came to consensus and agreed to leave their camp. This was not a surrender.

Chaos ensued as the army tried to arrest the adults. A 14-year-old girl was bayoneted in the chest but miraculously survived. Children were separated from their parents by the militia. The men and women were beaten, handcuffed and put on buses - one for the men and another for the women.

Canadians paid $155 million to terrorize Mohawk men, women and children defending their unceded land and protecting their sacred burial ground from immoral development. Yet, the land issue remaines unresolved.

By July 11, 1991 all but three of those arrested had been acquitted by juries and you can be sure it was definitely not juries of their peers.

This year, Quevillion once again raised the threat of an uprising against the people of Kanesatake because a developer realized this unceded land should be returned to its rightful guardians. Despite his apology to Chief Simon, Quevillion needs to realize that he lives and governs in very different times.

If Quevillion continues to block Gollin's efforts, he should in no way be surprised when local, provincial, national and international support for the people of Kanesatake proves more than his little band of racist settlers can handle.

This is 2019, and thanks to Alanis Obomsawin the world not only knows the truth, it acknowledges the Mohawk Nation's rights to the disputed land.

For a more comprehensive history of the Kanesatake crisis, watch Alanis Obomsawin's documentary: Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993 NFB; 2 hours), available free on the NFB website.

Released in 1993, this landmark documentary has been seen around the world, winning over a dozen international awards and making history at the Toronto International Film Festival, where it became the first documentary ever to win the Best Canadian Feature award.

A great follow-up is Obomsawin's short documentary, My Name Is Kahentiiosta (1995 NFB; 30 miniutes). This film recounts the story of Kahentiiosta, a young Kahnawake Mohawk woman arrested at Kanesatake after the 78-day armed standoff. Kahentiiosta was detained four days longer than the other women because the prosecutor representing the Quebec government refused to accept her Indigenous name.

Family studies, history, social justice, and art teachers will find a wealth of material on which to base meaningful lessons that can be tied to: abuse of political power, the role of the media, Treaty rights, 600 First Nations, family dynamics, the impact of governmental abuse on children including numbering and renaming children in residential schools, supporting Indigenous languages, land stewardship, climate change, and Truth and Reconciliation, as well as these key dates:

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?