Public historical monuments are important. They can and should be powerful tools to help us remember and contextualize our shared history. But they should be unambiguous about refusing to celebrate the bad men of history.

By Tom Shea

Published August 21, 2017

This article has been updated.

A friend asked me what I thought about US President Donald Trump's warning of a "slippery slope" when removing public monuments dedicated to Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and other bad men of their Confederate ilk.

Of course it is important to remember history - all of it, even the dark parts. But when we erect public statues of victorious men on horses (always men, always horses) we do so to celebrate their victories, not merely to remember them.

I would never suggest we hide the darkness of history away in museums, but I would advocate for public statuary that celebrates the true heroes - the abolitionists, the underground railroad operators, the freedom fighters - or that memorialize the victims.

This is not a radical idea. Tour the Shoah museum. Tour the Vietnam veterans memorial wall. Go to Dieppe, or Ypres. Go to the Halifax pier and follow the hob-nailed boot prints of the thousands of doomed young soldiers who boarded ships to fight fascism. There it is: history on full display.

You might feel pride for those who struggled, sorrow for those who died. You'll see precious little public statuary devoted to those who fought for evil goals.

But it is important to remember the dark times, too, the evil people and the grim places - not just privately, but publicly. The Musee de la Gaspesie provides a quick example of how to do it right.

I toured the Gaspé peninsula this summer. The town of Gaspé is the purported site of Jacques Cartier's landfall in North America, and so, in addition to being a sleepy gem of a tourist town on the edge of the Atlantic, it is effectively ground zero for European colonialism and genocide in the Americas. (Fun fact: even the name "Gaspé" itself is stolen from the Mi'kmaq.)

There has for a long time been a cross planted at the site of Cartier's first encampment: a massive granite monolith, created by the Government of Canada "for the 400th anniversary celebrations of Jacques Cartier's arrival in 1934."

It is grand, imposing, and - by its own admission - celebratory. It also is a model of uncritical and univocal historiography as practiced a century ago. When Canadian history was primarily a history of colonialism, told by colonizers, the cross stood alone and self-explanatory, a symbol of arrival, victory, progress.

However, any thinking citizen of North America should have deeply conflicted feelings about Cartier. We are only here at all because he braved the terrors of the Atlantic and came here first; but we are also only here because he was the leading edge of a systematic and institutionally-legitimized racist program of re-education, exploitation, and genocide that killed millions and stole the land, language, and culture from the survivors.

Our current comfort and prosperity in Canada was bitterly bought by the agenda of murder and thievery he enthusiastically represented. That's an uncomfortable thought if ever there was one, but it's a thought that we should all be forced to sit with on a regular basis.

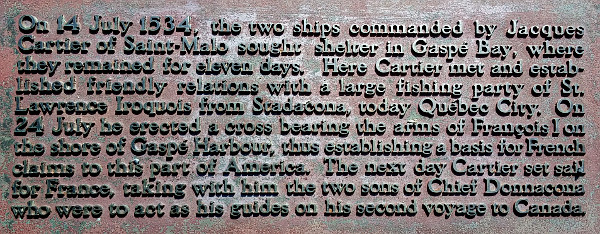

There is a second cross at Gaspé. It is a slender wooden recreation of the one Cartier erected in 1534, complete with fleurs-de-lis banner and inscribed "Vive le Roy de France."

Cross celebrating the site of Jacques Cartier's first encampment

It stands in a manicured but unadorned clearing by the water's edge. Although humbler in construction and placement, like the granite cross of 1934, it is an unequivocal symbol of European Christians conquering the local Mi'kmaq.

However, to get to this second cross, you need to park at the top of a nearby hill; walk past a local artist's statue of Mother Earth; pass through a sculpture garden where massive tooth-like bronzes erupt from the gravel with illustrated scenes depicting passages from Cartier's journal on one side, illustrated images of the same scenes from an imagined First Nations perspective on the obverse.

Sculpture garden. The statue La sculpture "En mémoire d'Elle" was created by the Gaspesienne artist Renée Mao Clavet.

Only then - only after acknowledging the land, after seeing the minds of the colonists and the impacts of colonialism on the local populace, only after reading about Cartier's overt racism, after hearing how Cartier kidnapped the local chief's two sons to convert them to Christianity, teach them French, and use them as interpreters for his next expedition - only then do you get to the cross. By the time we arrived, I was fighting back tears.

When I asked my 12-year-old son what he thought of it all, he pondered a moment and then said "Jacques Cartier was a jerk." This was the beginning of a sombre conversation that continued throughout our trip. The Cartier site came with us and informed many of our other historical stops.

Public historical monuments are important. They can and should be powerful tools to help us remember and contextualize our shared history. But they should be unambiguous about refusing to celebrate the bad men of history.

They should remind us why bad things happened, how we stopped those things, and how to prevent them from happening in the future.

Sure, we should remember the Stonewall Jacksons, the Robert E. Lees, the Jacques Cartiers. But we should never uncritically celebrate them in our public spaces. They're not the people who deserve pride of place in the town square.

Update: this article erroneously referred to the cross at Gaspé as "an unequivocal symbol of European Christians conquering the local Iroquois." The First Nation Cartier encountered were Mi'kmaq, not Iroquois. RTH regrets the error. You can jump to the changed paragraph.

By KevinLove (registered) | Posted August 25, 2017 at 17:52:21

But when we erect public statues of victorious men on horses (always men, always horses)

Does Hamilton have a single statue of a victorious man on a horse? I have not been to Battlefield Park for a while, but do not remember any equestrian statues there. Google certainly knows of no such statue

As an Army veteran, I can certainly affirm the sentiment on the dedication stone of the Battlefield Park monument:

More dearly than their lives they held those principles and traditions of British liberty of which Canada is the inheritor.

As far as I know, the only public statue we have in Hamilton of a military commander is of a woman, and she is not on a horse.

Comment edited by KevinLove on 2017-08-25 17:53:06

By treys (registered) | Posted September 02, 2017 at 12:39:39

Queen Victoria statue in Gore Park, (not a man, not on a horse). I'm proud to be a man and a christian. Somehow that is not PC anymore.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?