The survival of St. Paul's, a wooden church built in the late 19th century, is quite remarkable and it is worth visiting for its expression of the ecclesiological principles of Anglican Church design.

By Malcolm Thurlby

Published September 05, 2010

Wooden Anglican churches in Ontario of the second half of the 19th century are not plentiful. In the first place, rich, large and/or more ambitious congregations opted to build their churches in stone or brick rather than wood because a masonry edifice was seen to be more permanent. Secondly, wooden edifices were more susceptible to destruction by fire.

The survival of St Paul's Anglican Church in the village of Middleport, located on Highway #54 about 22km east-southeast of Brantford, is therefore quite remarkable (Figs 1-3). The History of Brant County published in 1883, records that St Paul's was 'erected during the year of 1868, on an eligible plot of ground, the gift of Robert Wade, Esq.'. The church is described as 'A neat frame building with tower and bell, its value being $1,500'. St Paul's was consecrated in 1880 by Isaac Hellmuth (1817-1901), Bishop of Huron (1871-1883).

Fig. 1. Middleport, St Paul's Anglican Church, exterior from NE.

Fig. 2. Middleport, St Paul's Anglican Church, exterior from SE.

Fig. 3. Middleport, St Paul's Anglican Church, exterior from SW.

The church history informs us that St Paul's was erected 'under the direction of Reverend Adam Elliott' but the name of the architect is not recorded. Be that as it may, it is clear that the person was well informed about ecclesiological principles of Anglican Church design. In a number of articles on heritage churches in Hamilton and vicinity I have acquainted RTH readers with some of the principles of the 'science of ecclesiology', as it was labeled in early Victorian times.

Here I wish to introduce a book by the English architect James Barr, entitled Anglican Church Architecture, with some remarks upon Ecclesiastical Furniture. The book was first published in 1842 and is dedicated to the Oxford Society for Promoting the Study of Gothic Architecture. A second edition followed in 1843, and a third in 1846. Happily, the latter is now available online.

Barr's book is seldom referred to in studies of 19th-century-church architecture, yet this 'little work', as Barr himself calls it, is just the sort of publication that was so important for the dissemination of 'correct' Gothic design of Anglican churches throughout the world. As a review of the second edition of the book in The Gentleman's Magazine, volume 20 (1843), p. 499 concludes:

We cannot close our account of this little volume without a strong recommendation in its favour, not only on account of its utility to the inquirer of the history and details of Gothic architecture, but also for the sound and correct church principles which it conveys.

St Paul's, Middleport, conforms for the most part to the principles of ecclesiological design, with a separate nave, lower and narrower chancel, a vestry to the north of the chancel, and a west tower surmounted by a spire (Figs 1-3). The board-and-batten construction provides vertical articulation that is lacking in clapboard siding, as on the tower of Old St Thomas Anglican Church, St Thomas, Ontario (1824) (Figs 3 and 4).

At Old St Thomas, the sham crenellation on the tower and façade wall of the nave, the low pitch of the roof, the broad transept (added in 1848), and the multi-paned windows with intersecting muntin bars in the pointed head, are all features that are 'corrected' at St Paul's. Similar contrasts are evident inside the two churches.

At St Paul's the principal rafters, braces and tie beams are truthfully exposed; there is a step up to the chancel and another to the altar, and there is open seating (Fig. 5). At Old St Thomas, there is a lath-and-plaster ceiling, box pews, galleries in the transepts, and no distinct space for the chancel, all features abhorred by the Ecclesiologists (Fig. 6). At St Paul's pointed arches are used throughout and the triple lancet windows in the east wall of the chancel, and the single lancets in the nave, are filled with stained glass.

Fig. 4. St Thomas, ON, Old St Thomas's Anglican, exterior from S.

Fig. 5. Middleport, St Paul's Anglican Church, interior to E.

Fig. 6. St Thomas, ON, Old St Thomas's Anglican, interior from SW.

The differences between Old St Thomas and St Paul's are all accounted for with reference to Barr's book. He states that the plan of the church should comprise nave and chancel with the Holy Table elevated at the east end 'for the more impressive celebration of the Lord's Supper' (fig. 4).

Barr is less authoritarian than the strict Ecclesiologists on the size of the chancel. He observes that '[t]he relative proportions of the different parts of the sacred structure, are so various in old examples, that with our present limited knowledge of the principles of design in Ecclesiastical Architecture, it is impossible to lay down any definite rules upon the subject'.

He does point out that the chancel should not exceed thirty feet in length 'since the Priest at the altar will be too far removed from the congregation to be distinctly heard'. He calls for the high pitch of the roof and indicates that the nave roof higher should be higher than that of the chancel. He advocates the inclusion of stained glass windows and points out that:

When only common glass is used in Ecclesiastical structures, it should be in small panes, disposed diagonally, or in various geometrical figures, so as to afford a decided contrast, both to the horizontal and vertical lines of the windows; the lights when filled with diapered quarries, relieved by little pieces of colour, and surrounded by rich borders, have a very pleasing and brilliant appearance.

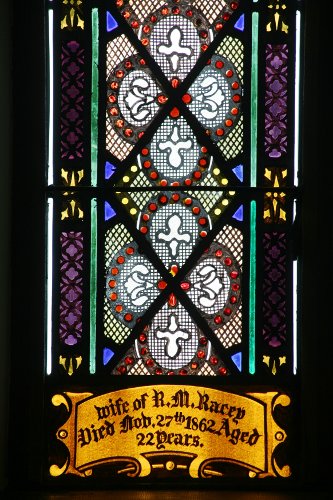

This is exactly what we find in the nave windows at St Paul's (Fig. 7). It should be noted that the 1883 History of the Country of Brant records 'The beautiful memorial window in the chancel was the joint gift of Robert Racey and Rev. Adam Elliott. It was erected in memory of the latter's nephew and niece. The side and north windows were the gift of Mr. Cooper of the village of Mount Pleasant' (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7. Middleport, St Paul's Anglican Church, nave window detail.

Fig. 8. Middleport, St Paul's Anglican Church, chancel window detail.

On the vestry, Barr suggests that 'a small vestry of unpretending design might also be placed on the north or south side of the chancel but must never be made an important feature in the composition' (Fig. 1). He adds that 'The Vestry, or Sacristy, is built on the north or south side of the Chancel, and when kept properly subservient to the general design does not detract from the beauty of the structure to which it is annexed...' 'The Vestry is entered by a small doorway in the side wall of the Chancel' (Fig. 5).

Barr calls for a porch on the north or south side of the nave and adds '[a] western porch should not be introduced, unless the locality of the sacred edifice requires such an arrangement'. At St Paul's the side porch was deemed superfluous as the main entrance is through the tower which faces the road.

Barr recommends the use of a tower 'for containing the bells, which require to be suspended at a considerable elevation, in order that they be heard at a distance; it also serves to point out the situation of the sacred edifice, and is useful as a beacon for the guidance of travellers, being often a conspicuous object for miles around'. He adds: 'A spire "pointing in silence heavenward," is by far the most beautiful covering for the tower'.

The font is located towards the west end of the nave close to the entrance to the church, as advocated by Barr (Figs 9 and 10). It is wooden and stands on tall pedestal the proportions of which have more to do with post-Reformation font design than with medieval exemplars. Be that as it may, the scale of the font is better suited to the small dimensions of the nave of St Paul's in which space a larger, medieval-inspired design would have been too large.

Fig. 9. Middleport, St Paul's Anglican Church, interior to W.

Fig. 10. Middleport, St Paul's Anglican Church, font.

Fig. 10a. Middleport, St Paul's Anglican Church, lectern.

Moreover, the use of wood for a font, while unusual, finds precedent in medieval England and Wales, and the moulding of the capital and base follow 13th-century precedent. Similarly with the lectern, the central column with nail-head ornament between the delicate corner shafts, and the sunk quatrefoils on the plinth and the front of the lectern follow Early English models (Fig. 10a).

The simple open seats with pointed arches on the bench ends conform to the strict ecclesiological principle of social equality in seating (Fig. 11). Barr states:

All the Pews should be of the same description, and those allotted to the poor ought never to be in an inferior situation, for this invidious custom is not only entirely opposed to the spirit of Christianity, but has thus been distinctly condemned by the holy Apostle St James: "If there come unto your assembly a man with a gold ring, in goodly apparel, and there come in also a poor man in vile raiment; and ye have respect to him that weareth the gay clothing, and say unto him, Sit thou here in a good place; and say to the poor, Stand thou there, or sit here under my footstool; are ye not then partial in yourselves, and are become judges of evil thoughts?"

High Church Anglican arrangements of the Ecclesiologists would have demanded a pulpit and a lectern to either side of the chancel arch. The lectern is included at St Paul's, on the left of the chancel arch, and also a reader's desk, or reading pew, on the right (Fig. 12), something outlawed by the strict Ecclesiologists but accepted, if grudgingly, by our rather more liberal James Barr.

He points out that there is 'no ancient authority' (i.e. no medieval precedent) for the reader's pew, 'but if introduced, it ought always to be of simple design instead of being made a lofty and prominent erection like a pulpit, as it is not requisite for the Clergyman when praying to be exalted above the people'.

While not specifically discussed by Barr, the articulation of the interior of the sanctuary walls of St Paul's with a wooden dado of pointed arches is in contrast to the simple wainscoting elsewhere in the church and serves to emphasize the importance of the space around the altar in accordance with ecclesiological principles (Fig. 12).

Fig. 11. Middleport, St Paul's Anglican Church, bench ends.

Fig. 12. Middleport, St Paul's Anglican Church, chancel.

Barr makes no reference to wooden church construction. Yet the design of churches in wood according to ecclesiological principles was of great concern to Anglican church patrons in British North America from the 1840s on.

In 1843 Mr. Patterson addressed the Oxford Society for Promoting the Study of Gothic Architecture (OSPSGA) and presented lithographs of wooden churches in Norway. He read in translation from Johan Christian Dahl's three-volume book on Norwegian stave churches published in Dresden in 1837 and which was listed in the library catalogue of the society in 1846. Discussion following the paper mentioned that the churches could serve as models for wooden churches in Newfoundland and the Canadas. (pp. 150-156 on the website).

While these Norwegian stave churches did not influence the design of Anglican churches in Newfoundland or elsewhere in the Maritimes, or Upper or Lower Canada, the tall proportions of Holy Trinity, Stanley Mission, Saskatchewan, built by the Anglican missionary, Reverend Robert Hunt, between 1854 and 1860, indicates knowledge of stave churches, perhaps a tracing of one of Dahl's lithographs supplied by the Oxford Architectural Society (Figs. 13 and 14).

Fig. 13. Urnes (Norway), Stave Church, after J.C. Dahl (1837).

Fig. 14. Stanley Mission, SK, Holy Trinity Anglican Church, exterior.

In the OSPSGA Proceedings for the meeting of February 28, 1844, we read that 'A letter was read by the Chairman from the Rev. G[eorge] Coster, Archdeacon of New Brunswick, acknowledging a present of the publications of the Society and expressing a warm interest in its proceedings. The Chairman took this opportunity again to call the attention of the Society to the subject of designs for wooden Churches for the Colonies'.

At the meeting of the OSPSGA of May 15, 1844, there was exhibited 'a design by Mr. Cranstoun for a wooden Church, according to the suggestion of the Bishop of Newfoundland'. At the June 17 meeting it is reported that two of Mr. Cranstoun's designs for wooden Churches, prepared 'under the directions of the Committee', were now ready. On April 16, 1845, Mr Millard addressed the OSPSGA on 'The Style of Architecture to be adopted in Colonial Churches', the text of which was published in the Proceedings of the Society.

John Medley, Bishop of Fredericton, New Brunswick, 1845-1892, addressed the Ecclesiological Society on May 9, 1848, said '[The Society] might...aid me much by small plain wooden models for wooden churches in the country. In many places it is absolutely impossible to build of stone, from the frightful expense of materials and workmen...And most of the men being carpenters in some sort, they easily get out the frames of our churches (The Ecclesiologist, VIII, 362-363).

In a seminal article entitled 'On Wooden Churches', published in The Ecclsiologist, IX (1848), 14-27, William Scott warned against the 'Log Church' of Canada which was based on 'the old heathen temples of the Canadian Indians'. He advocated the use of vertical logs as in the nave of the Anglo-Saxon church at Greenstead-juxta-Ongar (Essex). If planks were to be used then the Norwegian model of vertical planks should be used rather than added that 'there seems to be no reason of the horizontal arrangement which prevails in America'. Scott believed that the pitch of the roof should be step as in the stave churches.

In Newfoundland and Labrador a number of wooden churches were built to the design of Scottish architect William Hay (1818-1888), who arrived in Newfoundland in 1847 to act as Clerk of Works for English architect George Gilbert Scott who designed the Anglican cathedral of St John's. Hay's design of the wooden Anglican Mission Church for St Francis Harbour, Labrador, was made known to the Ecclesiological Society by means of a lithograph and was given the rare distinction of a favourable review in their journal, The Ecclesiologist (vol. 11, 1850, pp. 201-202.

On Newfoundland churches, see the excellent book by Peter Coffman, Newfoundland Gothic (Montreal: Collection Cahiers de l'institut du patrimoine de l'UQAM), available at amazonbooks.ca).In 1853 William Hay moved to Toronto where he established a successful architectural practice. Hay designed many churches of which the best preserved are All Saints, Niagara Falls (recently closed), St Andrew's Presbyterian at Guelph, St Luke's, Vienna; and Zorra (just south of Tavistock on Highway #59).

He also designed the board-and-batten Garrison Church in Toronto. The Garrison Church has not survived but its design is reflected in the extant St Thomas's Anglican Church, Brooklin (Whitby), by Hay's pupil, Henry Langley.

John Turner was supervising architect for William Hay's Grace Anglican Church, Brantford, in which ecclesiological principles are followed. Turner applied these principles assiduously in the chancel he added to St James's Anglican in Paris (1863) and in St Paul's Indian Mission Church (1866). Concomitantly, the use of board and batten at St Paul's, Middleton, may be derived from William Hay through John Turner, and it is possible that Turner himself was the architect.

Be that as it may, there is an alternate explanation. The English-trained architect, Frank Wills, used board-and-batten construction for Grace Church, Albany, New York, built in 1850, which he described and illustrated in his book, Ancient English Ecclesiastical Architecture and Its Principles Applied to the Wants of the Church at the Present Day (New York: Stanford and Swords, 1850), available online) (Fig. 15).

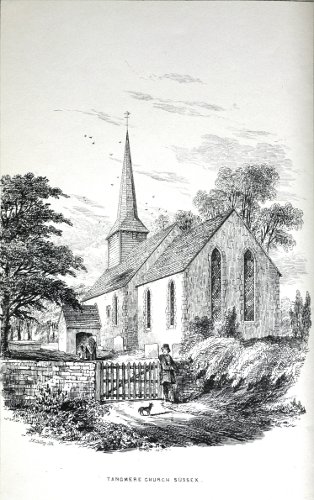

Wills also designed the wooden church of St Mary's, Cainsville, just east of Brantford, which did not survive past the 19th century. Other sources in the architectural press may have played a part in the creation of the design of St Paul's, Middleport. The proportions of the spire recall Tangmere (Sussex), illustrated in Raphael and J. Arthur Brandon's Parish Churches published in 1851 (Fig. 16).

Fig. 15. Albany, New York, Grace Church, Frank Wills, 1850.

Fig. 16. Tangmere Church (Sussex), from Brandon's Parish Churches (1851).

The design for a country church by Richard Upjohn (1802-1878), author of Upjohn's Rural Architecture: Designs, Working Drawings and Specifications for a Wooden Church, and Other Rural Structures, published in 1852, shows board and batten - nave and chancel and main entrance through the tower with spire in the position of a south porch like Middleport has tower-porch at the west.

For those of you who would like to visit St Paul's Anglican Church, Middleport, it is included in this year's Doors Open Brant, September 25, 10am - 4pm. Thanksgiving Service will be held at St Paul's at 2.30pm on Sunday, October 3.

Readers who fancy excursions a little further afield to see other board-and-batten Anglican churches, one other example may be introduced. St Andrew's-by-the-Lake, Turkey Point, ON (1861) has a two-cell plan with nave and chancel, like St Paul's, Middleport, along with 'correctly' proportioned lancet windows and steeply pitched roofs. St Andrew's-by-the-Lake lacks the monumental tower and spire of St Paul's but does include a south porch and belfry at the west end of the nave roof, both according to ecclesiological principles.

By adrian (registered) | Posted September 05, 2010 at 13:37:44

Beautiful photographs and fascinating history.

By Tybalt (registered) | Posted September 07, 2010 at 10:59:26

This was great. The photos remind me of many churches (both Anglican and dissenting) back home in Nova Scotia.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?