While Howard's design for St. James would not be mistaken for a medieval original, it, along with most of his other designs, does indicate that the architect espoused principles of Gothic as applied to Anglican church design in England.

By Candace Iron and Malcolm Thurlby

Published July 11, 2010

The publication online of Robert G. Hill's Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada 1800-1950 is a great contribution to the study of the history of architecture in Canada. Painstakingly researched over 24 years, Hill tells us that:

This website is intended to be an authoritative work of reference for the history of Canadian architecture during the study period of 1800 to 1950, and it contains biographies of nearly 1,700 architects who lived and worked in Canada as well as those architects who resided in the United States, Britain and elsewhere, and for whom it is now possible to link their names with buildings constructed in this country.

This Dictionary website lists every Canadian building of importance between 1800 and 1950 whose architect can be identified, together with essential information on the date of design, construction, alteration or demolition of the work. It is based on extensive original research conducted over a period of twenty-four years, much of it unpublished, and provides critically important information including the names of many Canadian architects previously unknown, as well as references to many buildings whose authorship is recorded nowhere else. Every citation of fact is based on the original sources quoted in the entries.

It would be hard to imagine a more important tool for those interested in researching heritage buildings in Canada and their architects. It serves as the fundamental and easily accessible starting point for the collection of essential references. One such entry is significant for this essay, the list of buildings designed by Toronto-based architect John G. Howard (1803-1890).

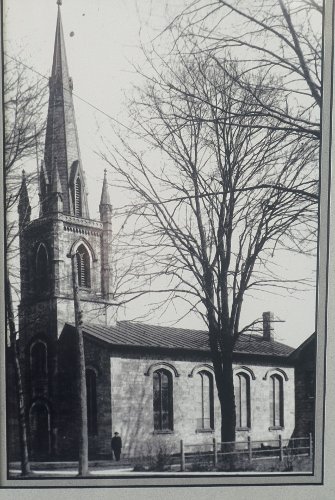

Howard's Anglican church of St James, Hatt Street, Dundas (1841-43) has not survived but in the parlour of the present St James' there hangs a photograph of the exterior of Howard's church. St James was opened for services in December 1843 and served the congregation until 1925 when the new church was commenced on Melville Street. This church was destroyed by fire in January 1978, after which a third church was constructed, which opened for services in April 1980.

Dundas, St James's Anglican Church, exterior, John G. Howard, architect (1841-1843), archival photograph.

Born John Corby in Bengeo (Hertfordshire) on July 27, 1803, our architect changed his name to Howard in 1832. Starting in 1824 he trained with London architect William Ford for three years. In 1832 he moved to Toronto where he worked as an architect, surveyor and, between 1833 and 1856, master of geometrical (technical) drawing at Upper Canada College.

In 1833 Howard was also commissioned by the Bishop of Quebec, whose diocese included Upper Canada, to prepare architectural drawings for Anglican churches which could be lithographed and distributed amongst parishes in need of designs.

Howard's St James, Hatt Street, Dundas, was a fine example of Gothic revival ecclesiastical architecture in Ontario in the early 1840s at which time we begin to witness a more complete understanding of medieval Gothic architecture than seen earlier in the Province.

The Revival of Gothic architecture in Canada had its beginnings in the 'romantic' or 'picturesque' phase of the style, wherein Gothic ornament was applied to otherwise classically-inspired church buildings. This 'picturesque' style was slowly replaced in the 1820's by the so-called Commissioners' style, which in some cases, was rooted in a more academic study of Gothic architecture than its predecessor had been. This Commissioners' style, which took its name from the Church Building Commission in Britain that was established after the Church Building Act of 1818, is, for the most part, the tradition that Howard's Anglican churches come from.

The Church Building Act, which supplied £1,000,000 for new Anglican church buildings in Britain, was not specific on the matter of style, but some architects suggested that Gothic was less expensive than a classical alternative. It was reported that of the 214 churches that resulted from the 1818 Act, 174 were Gothic.

While the quality of these churches varied considerably, the sheer weight of numbers could only further raise interest in the revival of the Gothic style for ecclesiastical architecture. In America, Ithiel Town's (1784-1844), Trinity Church, New Haven, CT, 1817, is Gothic, and Town himself reports that "the Gothic style of architecture has been chosen and adhered to in the erection of this Church, as being in some respects more appropriate, and better suited to the solemn purposes of religious worship."

While 18th- and early 19th-century Gothic architecture owed more to the study of medieval church monuments and fittings than to the study of medieval Gothic architecture, several of the architects of Commissioners' churches turned to English medieval architectural sources for inspiration.

The 1817 publication of Thomas Rickman's book entitled, An Attempt to Discriminate the Styles of Architecture in England from the Conquest to the Reformation, stimulated interest in the study of medieval architecture, as did John Britton's five-volume, Architectural Antiquities (1807-1826), and 14-volume Cathedral Antiquities (1814-1835).

The trend continued with works like Matthew Holbeche Bloxham's, Principles of Gothic Architecture (1829). The revival of Gothic architecture received unprecedented stimulus with the English architect and theorist, Augustus Welby Pugin (1812-52). Pugin, a convert to Catholicism, was passionate about Gothic, and believed it was the only appropriate style for churches.

Gothic was Christian, and opposite to the Classical tradition in architecture which was associated with the pagan gods of Antiquity. Pugin's first book entitled Contrasts: or, A Parallel between the Noble Edifices of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, and Corresponding Buildings of the Present Day; shewing the Present Decay of Taste; Accompanied by appropriate text, was privately published in 1836 and reissued by a commercial press in 1841.

The book advocated Gothic as the only style for church architecture, and was reinforced in Pugin's next publication, The True Principles of Pointed Architecture (1841), in which he argued for the careful study of Medieval Gothic buildings and constructional techniques of the Middle Ages as the basis for a correct revival of the style.

Pugin's views were shared by many High Church Anglican contemporaries. In 1839 a group of Cambridge undergraduates founded the Camden Society, renamed the Ecclesiological Society in 1846. These ecclesiologists studied medieval churches and their furnishings with the view to the "restoration of mutilated Architectural remains" and the revival of ritualistic worship in a Gothic setting.

In 1839 they published a pamphlet entitled, A Few Hints on the Practical Study of Ecclesiastical Antiquities, and this was followed in 1841 with, A Few Words to Church Builders. In 1841 they also began to express their views in the quarterly journal, The Ecclesiologist.

1839 also saw the foundation of the Oxford Society for Promoting the Study of Gothic Architecture, renamed The Oxford Architectural Society in 1848, which had analogous aims to the Camden Society and published their Proceedings starting in 1840.

The rapid developments in the study and revival of Gothic architecture in the late 1830s and 1840s were reported in an increasing number of specialized publications, not least through the offices of John Henry Parker in Oxford. In addition, the inception in 1843 of the weekly journal entitled The Builder, announced the latest developments in English architecture to architectural professionals, like John G. Howard, throughout the English-speaking world.

A report on the "Laying of the Foundation of St James's Church, Dundas," published in the Anglican newspaper entitled, The Church (11 Sept. 1841, 38), informs us that:

The building, which is now far advanced, is of the Gothic style of architecture, and its beautiful symmetry, which is already discernible, reflects the greatest credit upon J.G. Howard, Esq., Architect of Toronto, to whom the Building Committee, and the congregation generally feel themselves under many obligations for his handsome present of the excellent plans, specifications, &c.

The body of the church, which is of the finest description of Freestone, neatly hammered, and laid in courses, with cut stone corners, door and window jambs, sills, water table &c. is 40ft wide, by 65 feet in length, with a tower projecting four feet, making its extreme length outside 69ft. The interior is arranged for side galleries, and, when they are completed, it will easily accommodate five hundred persons, with comfortable sittings. The ceremony of laying the corner stone of this edifice took place on Tuesday, the 3rd August, in the presence of a very large and respectable assembly.

Just over two weeks later, on Wednesday, August 18, 1841, the cornerstone was laid of another church designed by John G. Howard, Holy Trinity, Chippawa. Howard's church replaced the original frame church of 1822 which had burned on September 13, 1839.

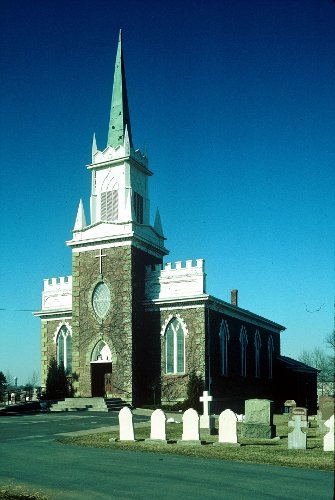

Howard's Holy Trinity Anglican Church, Chippawa, provides many points of comparison and contrast to St James's. In plan the two buildings are similar with a rectangular nave and a tower that projects slightly in the centre of the entrance façade. Both churches have an octagonal spire atop the tower, four pointed windows on each side of the nave, an entrance in the tower, and a window in the wall to the left and right of the tower.

Holy Trinity is built largely of red brick with stone dressings for window and door heads, the frame of the vesica-shaped window in the tower, and the quoins (corner stones). Features like the regular, emphasized quoins, projecting keystones of the windows and doorway, and the dentil range (row of small square blocks) on the underside of the cornice on both the nave and the tower are derived firmly from the classical tradition and owe nothing to medieval precedent. Such motifs were well established in classicizing buildings of the 1820s and 1830s in Ontario, as at St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church, Niagara-on-the-Lake.

Chippawa, Holy Trinity Anglican Church, exterior from W, John G. Howard, architect (1841)

Very few examples of classicizing Anglican churches still exist in Ontario, as most were replaced by the preferred Gothic style by the mid-19th century; however, a late example can be found at Christ Church, Vittoria (c.1844).

Equally alien to medieval building practices is the inclusion of the crenellated wooden screen on top of the west wall of the nave to either side of the tower at Chippawa. These features were most often included in 'picturesque' Gothic buildings and conceal the low pitch of the gabled roof. Something similar is found on the façade of Old St Thomas's Anglican Church, St Thomas, ON, of 1824.

St Thomas, Old St Thomas Anglican Church, exterior (1824).

Moreover, a circa 1860 photograph of Holy Trinity, Chippawa shows multi-paned windows with intersecting muntin bars in the pointed heads, exactly as at Old St Thomas.

Holy Trinity Anglican Church, Chippawa (Image Credit: Niagara Falls Public Library)

Such comparisons seem to suggest that Howard's design repeated details of the 1822 church, probably at the behest of the building committee. Likewise, the wooden belfry stage of the tower with intersecting tracery with the ogee arch above the belfry openings, and the wooden angle buttresses owe more to 18th-century 'romantic' Gothic revival than to medieval architectural models.

While it is more Gothic than not, Holy Trinity, Chippawa is the only church that Howard designed in such a 'romantic' eclectic manner, mixing the Classical and the Gothic.

In contrast to the red brick of Holy Trinity, St James, Dundas, was built of stone, in keeping with English medieval church-building practice. The windows and doorway have four-centred arches, so called because their form has two narrow arcs at the springing points with wider arcs for the upper trajectory of the arch.

Four-centred arches were introduced into English architecture in the 14th century and are characteristic of the so-called Perpendicular style, the last phase of English Gothic. Perpendicular included the Tudor period, 1485-1603, and sometimes the four-centred arch is called the Tudor arch.

The classicizing keystones of the Holy Trinity arches are abandoned at St. James and instead we find that a label or hood mould projects above the top of the window. According to Pugin's True Principles:

A hood mould projects immediately above the springing of the arch to receive the water running down the wall over the window, and convey it off on either side. This projection answers a purpose, and therefore is not only allowable but indispensable in the pointed style; but a projection down the sides of jamb, where it would be utterly useless, is never found among the monuments of [medieval] antiquity.

The windows in St. James are a simplified version of the two-light windows in King's College Chapel, Cambridge, illustrated in John Britton's Architectural Antiquities of Great Britain, volume 5, where we even find the horizontal termination to the hood mould. St James's belfry opening may be derived from the two-light geometric bar-tracery window illustrated in the same volume.

In contrast to Holy Trinity, the belfry at St James in constructed in stone and follows medieval precedent for the corbel table, the octagonal clasping buttresses surmounted by stone pinnacles, and the octagonal spire with lucarnes (gabled openings) on the cardinal faces and moulded strips on the angles of the octagon.

The inclusion of galleries would have met with strong disapproval from the Ecclesiologists, but the practicality of maximizing the number of seats in the church outweighed such theoretical ideals; and, in this connection, it is worth noting that St James's Anglican Cathedral in Toronto incorporated galleries when it was rebuilt after the 1849 fire.

In conclusion, St James's incorporates many features that derive from medieval Gothic architecture in keeping with the most progressive Commissioners' churches in England. While Howard's design would not be mistaken for a medieval original, it, along with most of his other designs, does indicate that the architect espoused principles of Gothic as applied to Anglican church design in England.

Indeed, the desire to be abreast of architectural developments in England remained foremost in Howard's mind throughout his career, a view he expressed during his retirement in a Letter to the Editor published in, The Builder, 28 (1870), 29 January, p.90, the leading British architectural journal published weekly from 1843, wherein he wrote:

I have been a constant reader of the Builder for many years, the numbers of which have so accumulated as to form almost a library of themselves. I am an old and worn out architect, and have retired to a snug retreat on the north shore of Lake Ontario, and look as regularly for my Builder every week as my Sunday's dinner.

By Magrill (anonymous) | Posted July 11, 2010 at 18:16:25

Howard was such an important architect in Ontario's 19th century, it is very encouraging to see excellent work on his buildings that were overshadowed by the Toronto contingent.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?