Maybe Hamilton's laneways hold real potential for new ways of living independently yet together.

By Emma Cubitt

Published April 09, 2020

Earlier this year, the Hamilton-Burlington Society of Architects organized a one-day design charrette with local designers imagining potential innovative solutions to the emerging crisis in housing affordability.

The specific focus was on housing for the millennial generation, and particularly home ownership opportunities. This emerging cohort of households is being priced out of the ownership market; while salaries have remained stagnant and employment has become more precarious, Hamilton's house prices have doubled or even tripled in the past decade.

Four teams of around 10 people - architects and intern architects from various firms, planners, urban designers, landscape architects, and artists - envisioned new types of housing for millennials in Hamilton. What could it looks like? What are the barriers to creating it? How much would it cost?

Teams situated their various scenarios on specific properties: LRT lands, a struggling mall, a rural site, and a typical urban laneway. After the one-day charrette, each team had a month to further develop the ideas into a proposal which was to be on display at the Carnegie Gallery in Dundas. Presentations of the ideas were set to happen on March 12th, and then the COVID-19 pandemic changed life as we knew it.

Social distancing and times of isolation afford opportunities to reflect on things in a different way. I wanted to share the ideas from my group that looked at ideas for a Hamilton laneway, in part to give inspiration to our collective imagination of what our post-pandemic future could hold.

When we come through this crisis, will everything go back to "normal"?

Will property values keep skyrocketing, compounding our housing crisis? Will banks change how they lend to younger people? We're realizing more than ever that safe and affordable homes are critical for public health, not just building a nest egg. Maybe Hamilton's laneways hold real potential for new ways of living independently yet together.

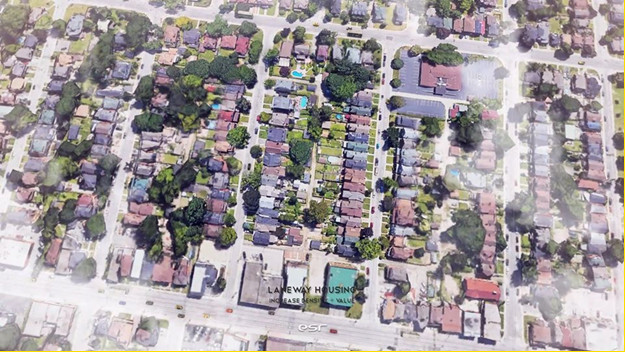

Image 1: View of the current site, a typical laneway in the St. Claire neighbourhood

The urban laneway is a present in most historic cities, with 100km of lanes in Hamilton. In the context of our current pandemic, it is interesting to realize that part of the reason alleys became underused was related to public health concerns about overcrowding.

Larger industrial cities that rapidly expanded often equated alley housing with disease, so many communities banned such developments - including Hamilton's 1957 bylaw limiting residential lots to one building with residential dwellings (no secondary buildings were allowed to have a legal second dwelling).

In reality, the backlash usually had less to do with actual disease prevention and more to do with stigmatized low-income renters who frequently lived in the unregulated and ad-hoc developments along urban laneways. As a result, for the past sixty years new lane-oriented homes have been prohibited in pretty much every North American city.

A new paradigm is emerging related to smart growth and sustainable development. Well-designed density can create more housing variety and opportunities, particularly improving communities that may have experienced population stagnation or decline. Lane-oriented sites can be economically advantageous, utilizing existing infrastructure and amenities, and can provide an attractive option for new households while maintaining the aesthetically appreciated historic character of neighbourhoods.

The reality is that Hamilton's existing urban residential neighbourhoods are often quite low density. The site for this proposal currently has roughly 20 households per hectare. By infilling underused spaces along the laneway, the density can be doubled without any demolitions of the existing historic neighbourhood housing stock.

While the City's new pilot laneway housing zoning bylaw is focused on secondary suites and rental units, (see my previous RTH articles Part 1 and Part 2), this design study imagined new options for home ownership - an idea which is currently not allowed, but could be.

Image 2: Snowy laneway photograph - existing conditions winter 2020

Our theoretical study is situated in the St. Clair neighborhood, located in lower Hamilton following the Niagara Escarpment south of Main Street East between Wentworth Street South and Sherman Avenue South.

Originally a white-collar neighbourhood, its quality-built urban fabric features streets lined with large brick homes. Victorian and Tudor-style homes predominate, and many have been beautifully maintained or restored. Large-scale high density urban redevelopment passed by this community, leaving the historic built environment intact and household density low. There is a small park two blocks to the west, and many amenities make this a walkable neighbourhood.

St. Clair's historic lots are of various widths and lengths, this typical block being 40m (130 feet) deep; its lanes typically feature older garages and other back-buildings. The lanes are generally "public unassumed", meaning municipally owned but not paved or maintained.

Delaware Avenue is the southern boundary of the study area, and home to particularly large lots and homes. The northern edge is Main Street East, a busy thoroughfare lined by low-rise apartment buildings, a restaurant, a church, and several commercial buildings converted from old homes. The surveyed fabric of the north-south streets is close, with a particularly tight 7 meter (23 feet) wide row of lots facing Gladstone Street. Properties facing Burris have wider properties that range between 8-10m (26-32 feet) wide.

The average cost of a home in St. Clair has tripled in recent years, limiting the range of households who can access the housing market. Much of the housing cost inflation in this neighbourhood has been fueled by people moving into Hamilton.

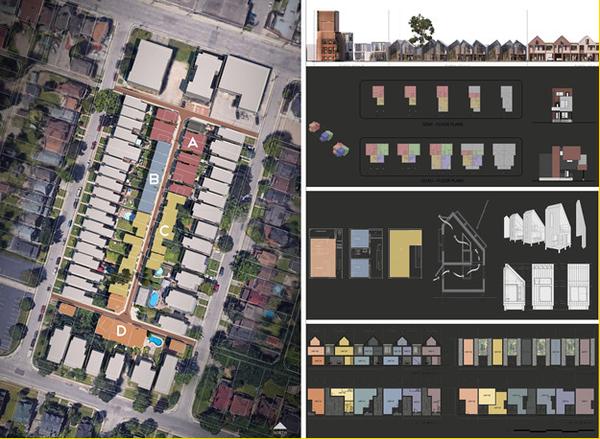

Image 3: the various housing typologies developed for our study: including detached and row houses and smaller apartment blocks. Unit sizes would range, along with price points for ownership.

Our proposal features site-scaled efficient plans and modular designs - two strategies to keep unit costs reasonable while being easily replicable as laneway projects are adopted in various communities over time. This could create the possibility for entering the housing market in the $300,000/unit range - a price point that is no longer available in the marketplace but which can be attainable for a household income around $46,000.

Some of the unit sizes and costs would be lower, closer to the $200k range, while larger houses would be more costly. This proposed laneway development could nearly double the number of households in this block without any demolition to existing housing. It offers a new ownership option for a range of household sizes and incomes. Our team's theoretical pro-forma financial calculations are linked here.

Image 4: Rendering of the development, showing the potential for activating the lane as a community space by widening it and creating a safe space for families and pets

This study explored a range of options, combined into one laneway for imagining maximum benefits. It shows the significant potential for laneway housing developments to improve historic neighbourhoods' densities without losing their built form. Each typology is a little different, demonstrating that there are multiple ways to address opportunities based on specific contexts.

A development of this scale could begin organically, with one or several property owners developing their rear yards for rental units under the city's new pilot bylaw. However to create infill at this full scale with homeownership, a new planning framework would be needed in terms of the increased density and land assembly of contiguous sites from willing owners.

Many existing homeowners could be willing to sell off the rear 10m of their property; in the pro-forma we listed the land value as around $35/ft2 site area or $20,000/unit).

Image 5: Proposed site plan for the laneway infill development, and some preliminary unit layouts

This proposal imagines a laneway development condo/strata corporation is created to purchase land on both sides of the laneway, to widen the access route from 3m to 6m for fire and EMS access, as well as allowing spaces for a more serviceable public realm. The rear of existing lots would be severed for development; while sales would be on a voluntary basis and at a fair price, various strategies explored recognize the importance of contiguous sites in order to achieve flexibility in designing both for laneway typologies and millennial households' need. The new lane, or woonerf, would be pedestrian friendly, with permeable paving and underground cisterns for stormwater management. Sharing infrastructure work would make developments more cost-effective; a budget of $500,000 (or $12,000/unit) was estimated for these features.

Image 6: potential back to back duplex units, as well as the new 6m wide lane or 'woonerf' which is a shared vehicle and pedestrian/ bicycle/child realm

Because this new infill develop would be relying on a traditional financial model of condominiums, and because the price points for these new dwellings is in line with current financing capacity of many millennial households, we would not expect financialization to be a major barrier. In fact, the main barrier we could envision would be getting buy-in from the first existing landowners interested in seeing this type of development in their rear yards. High quality design could help strengthen excitement, along with clear communication of the benefits to the existing neighbours such as added safety, paved and improved parking for those that still use the laneway, and in the likelihood of new neighbourhood amenities due to the added density - along with the $20,000 income from the sale of the rear of their lot.

Millennial demographics require design solutions be adaptable, providing viable options for a wide range of households, including single individuals, couples, families, and friends sharing accommodation. Affordability is paramount as real estate prices have rapidly outpaced incomes, preventing many in the millennial generation from having financial access to home-ownership.

Taking advantage of the length of the existing properties, this proposal explores the opportunity to provide adaptability within a standard, townhouse style format. These designs can accommodate between six and eleven units within a series of repeatable modules either 6 m or 9 m wide and potentially of varying depths.

Parking spaces are included throughout, and can be used by either the laneway residents or - where access is provided to an existing rear yard - by the street-facing homes. Balconies could either be shared or dedicated to a specific unit. Units may be combined or broken up to accommodate anything from studio units to four-bedroom units, but exterior dimensions would be consistent allowing for modular construction techniques.

An apparent 2½-storey building height and pitched roofs are used to echo the character of the surrounding neighbourhood, while the second floor balconies and intermediary green roofs add a more modern feel with both visual and environmental benefits.

Image 7: Lane-oriented rowhouses designed with flexibility in mind in 6m or 9m modules

Another area our study explored was creating a 'community hub', located at the southern T-junction of the laneway. It integrates 2- and 3-bedroom units to accommodate couples, families, and friends sharing accommodation. Its primary role is to provide the community with ancillary spaces that house vital amenities that one-bedroom infill units may not otherwise have.

The community hub includes a ground floor workshop, a meeting room, community roof garden, roof terrace, private party rooms, and pollinator green roofs. These resources would not only serve new residents but existing neighbours and give them a place at the heart of the laneway to meet, share, and grow.

Current parking patterns would be only moderately disrupted by this increased density, as many existing residents do not use their alley access for vehicle parking, favoring the convenience of front driveways or street-parking. Indeed, most of Hamilton's alley infrastructure is not utilized for vehicular parking. Most of the proposed laneway dwellings include parking within the development.

Image 8: Community Hub with more dense units at the T-junction in the lane, as well as shared amenity spaces

Creating desirable infill housing in the middle of an existing block takes imagination, which is where I believe this proposal excels. It suggests that new vitality, density, and security is possible in existing neighbourhoods without significantly altering the historic built fabric.

It makes use of existing civic infrastructure in new ways, while creating building types, morphologies, and scales that otherwise do not exist, providing diversity for different households. It encourages a new, mosr sustainable and community-minded way of living.

By studying the existing urban fabric of a typical downtown Hamilton block, we imagine possibilities for sustainable urban development that is strategic, incremental, and perhaps, delightfully unexpected.

Note: The laneway development team for the Missing Middle Design Charrette for the Hamilton-Burlington Society of Architects included Emma Cubitt, Scott Barmin, Michael Brisson, Ana Cruceru, Jennifer Kinnunen, Ryan Pagliaro, Shem Pryzemyslaw, Eric Reid, Mary Lou Tanner, Kathy Vogel, and Holland Young. All renderings are by Eric Reid (Facebook and Instagram). Join the Facebook group Hamilton Laneway Suites for updates on the progress of proposals like this as well as laneway suite applications under the current bylaws in the City of Hamilton.

By grok (registered) | Posted April 13, 2020 at 12:09:44

People are still using the Neoliberal code word 'affordability' in this context -- when the most IMMEDIATE issue REMAINS: THE ALMOST COMPLETE LACK OF PUBLIC HOUSING CONSTRUCTION FOR (@4?) DECADES, NOW. And not LEAST -- PUBLIC housing FOR the Homeless population of Ontari-ari-ari-O. 'Affordable' NECESSARILY implies PRIVATE ownership of any new housing stock. YES IT DOES (don't anyone deny it); and so remains an UNACCEPTABLE strategy for the working-class to support, if it wishes to gain an independent role in this process.

Unless, of course, people are ALL FOR the speculators and developers and slumlords and petty suburban supporters of the Neoliberal 'Free Market' police-state.

We already have all the construction plans we need. I suggest instead, right now, the IMMEDIATE, MASS CONSTRUCTION of TINY HOMES for the Homeless. Then maybe Millennials and other proletarianized service workers can look into that option too.

By sbwoodside (registered) - website | Posted May 14, 2020 at 19:27:31

Great article. I was really looking forward to the Carnegie Gallery presentation in March—I was at the door looking at the sign that it was cancelled. Could it be set up as a live virtual presentation?

There's a lot to like in the related bungalow court design of Dan Parolek / Opticos shown here: https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2017/11... . One particular benefit of that design is to concentrate the parking into a small parking lot at the back.

A couple of critiques:

• Your design uses up more than half of the frontage on the lane as parking garages, which I would argue is not very "woonerfy". In fact it looks pretty hostile to pedestrians and children playing.

• The modern design doesn't really fit in with the neighbourhood. It looks cool in renderings but, for example, the overhanging second floors with thin metal columns feel like they are defying gravity–a bit hostile to the public on the lane–a common issue with modernist designs.

Your proposal has many great aspects and it would be great to see the city further modify the rules to allow the land to be severed, with the consent of the owners, to create new laneway neighbourhoods.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?