Cities have been designed with the needs of men in mind, for a time when women did mostly unpaid work and community work. Women have different transport needs, but these realities are not reflected in our city building efforts. Why not?

By Maureen Wilson

Published October 23, 2017

I was just shy of 40 when I had my first child. I was older than most and dumber than many. I had never changed a diaper in my life. Children and babies were not part of my world and never had been. I went to school. I went to work. And leaned in.

I made little time for anything else, including my neighbours, my neighbourhood and my city. Ironically, I spent a career working in municipal government.

But everything changed with the birth of my first child. For the first time in my life, my guiding creed was failing me because I felt like I was failing.

I was the child of immigrants and beat the odds and learned to walk again after the doctors prepared me for life in a wheelchair. I came to believe that I could overcome anything if I just worked harder than everyone else.

I felt that I was failing at motherhood when I had never worked so hard at something in my life. I couldn't get my newborn to latch onto my breast properly. I didn't produce enough milk to pump anything. And I couldn't get her to sleep for longer than an hour at a time, despite following the advice of all the books from all the "experts".

One morning I was on the couch, wearing an old dress shirt and breastfeeding our daughter, when my husband kissed me goodbye and left for work. I was in the same position, wearing the same shirt, feeding my same child when he returned that night. Exhausted, isolated and feeling like a failure, I remember crying for what seemed like forever.

After more than a month into this cycle, I knew my health, the health of my child and the health of our home required me to change what I was doing and how I was doing it. I didn't just want to survive motherhood, I wanted to enjoy it.

I wanted my child to feel my love, not my sense of failure (yes, I was privileged). I decided to tune out all the advice and get out of the house. We were a one-car family, so with my daughter strapped to my chest, we set out to explore our city.

While motherhood initially restricted my otherwise unrestricted life, it opened the door to new worlds, new freedoms and a new pace. It opened my eyes and changed what I saw and how I came to see things.

My baby became my passport to becoming a flaneur - "a person who walks the city to experience the city". My baby's continuous need to breastfeed due to my low milk supply forced me to linger and lounge in places all over the city.

It was only then that I realized I had been excluded from most parts of my city and other cities because I was a woman.

Generally, women don't linger in public spaces if they're alone. Women don't wander urban places without a destination in mind. There is always need for a clear travel plan and an unspoken understanding of what time of day travel must occur. Women cannot afford to get lost. The risk of violence and intimidation curtails our movement and our use of space.

I discovered places to linger, to love and to loath.

I started bringing a notebook on our city journeys.

I began noticing where people walked, how they walked and how they got to where they were going.

I began to appreciate the shadowy spots and the sunny ones. And colours became more apparent. The dominance of grey in the city was often overwhelming but I began to see and seek out bursts of colour.

Buildings I had previously ignored suddenly became pieces of urban art. I started assessing which ones I liked and why, and their relationship to the street and the people on the street.

I gained a greater appreciation of the weather, its role in how and where baby and I travelled, where we could escape and where we didn't feel welcome.

Because I was still having to stop and breastfeed so often, I took note of the public spaces and the private ones. Which ones "worked" and for whom. I wrote down who I saw and who was missing.

I was struck by the noise. If my baby wasn't sleeping, I talked to her non-stop except when I couldn't. Multiple lanes of loud, rip-roaring traffic made conversation impossible. I wondered what this does, over time, to community.

The traffic also served as a barbed-wire fence. It was dangerous to get over, keeping people in who wanted to get out and keeping people out because: who would dare try to get in.

We discovered the nice quiets and the lonely quiets. Lonely quiets came from sameness in form and function, like neighbourhoods that emptied out during the day, void of other uses.

And I began to see a pattern of bias in our city's built form born of low expectations or no expectations of my neighbours living in certain parts of our city.

I got the hang of being a mother and a constant milker. My flaneur posse grew, even if my milk supply did not. In quick succession, more babies joined the ranks. They moved from my back to my side. And I started to see and experience the city through their eyes rather than my own.

When you become responsible for the life of another human being, there is a reduction in and clarity of needs. A child needs to feel love, touch and warmth. Children need food, sleep, stories and safety.

Before leaving any maternity ward in Hamilton, parents and guardians must prove they can provide safe transport of their newborn. Car seats and carriers are checked and double checked. Design is everything.

Oh, the irony. Because what awaits a child outside the hospital is anything but safe.

Hamilton is not the best place to raise a child. It is the best place to have your child killed or seriously maimed by a fast-moving car or truck.

It is a city that curtails a "normal" childhood of healthy forms of movement, of independence and discovery. It is a city built for speed and cars, not people and especially not for children. And it is all these things not by accident, but by design.

As my children started moving from my side and into school, my view of the city changed yet again.

I grew up in a very small mining town in northern Ontario. With the exception of two families, everyone looked the same, did the same thing and made the same amount of money. We were, in effect, classless and almost entirely white.

The variety of families we came across in city parks, on city streets and in many local libraries during our flaneur days was largely absent from my children's classrooms. Despite our urban setting, their classrooms looked a lot like mine. We saw many similarities and very few differences.

I started looking into school boundaries and the placement of magnet programs such as french immersion and the International Baccalaureat diploma program offered in select schools.

Boundaries and program placement were being used to stream low-income and new Canadians out of schools located in higher-income neighbourhoods. Concentrated poverty in a neighbourhood meant concentrated poverty in the classroom.

There is mounting evidence demonstrating that this amounts to a stick in the wheel of any child's trajectory, regardless of how hard they work.

Interestingly, I found that Hamilton's Catholic Board had been quietly but intentionally doing just the opposite - placing magnet programs in at risk neighbourhood schools as a way to achieve mixed income in the classroom.

The advantages at birth began to snowball while the crushing weight of disadvantage began to stockpile.

It was only when my children started playing school sports and travelling to other school gyms did we see more diversity and way more adversity.

When one of my children entered the ranks of a private sports club, I began to notice who played on school teams but were largely missing from select teams. The same held true for private music lessons, pottery and the arts.

There's a myth in sports culture that success depends on size. Wrong. It is first and foremost about opportunity and experience - how many times your hands are on the ball, the keyboard, or the paintbrush. So it is with life.

If we only pass the ball to the tall player, their at-birth advantage accumulates. They will never learn the value of passing to others and how the team - the people and structures around them - are central to their success and achievements.

We have allowed our neighbourhoods and our classrooms to become segregated by income and we keep passing the ball to the tall kid in our approach to city building.

We have moved away from the "common wheel" (Dr. John M. Davis), a view that progress is achieved when everyone moves forward together. We are adding to the advantages of the already advantaged and we are limiting opportunity and possibilities for everyone else. Our children are becoming strangers to difference, by design.

We have entered the early teenage years in our house and my view of the city has changed yet again. And there's not much to see. In terms of city building, two of my three children have joined the ranks of the invisible.

We don't plan for teenagers in our public realm and we especially don't plan for teenage girls. We have downloaded this responsibility to the private domain - private lessons, shopping malls, coffee houses, and private homes.

Golf is a dying sport. Kids are moving away from swinging clubs and bats, leaving behind swimsuits and ice skates. Part of it has to do with the move to costly elite sports and the location of newer facilities along the urban periphery, but part of it is also about changing preferences.

Growing numbers of teenagers are picking up skateboards, BMXs, inline skates and scooters. But you wouldn't know that by looking at our city's budget and city spaces.

The city places and spaces we make available to our youth is a measure of how much we value them and how much they feel valued. Done right, the design and location of these spaces can offer young people the opportunity to encounter difference, be part of the common wheel, and practice their citizenship.

This might be the hardest stop along my parenting journey. Parents spend the early years and every year thereafter creating the conditions to support their children in gaining strength, building character, valuing kindness and instilling confidence. We do this knowing full well a (#MeToo](https://twitter.com/hashtag/metoo?lang=en) world awaits them. It especially awaits our daughters.

We tell our daughters there's no limit to what they can do, while simultaneously preparing them to live with limits.

Please don't walk home alone. Please don't ride the bus alone at night. Please don't take the short cut through the park. Please text me when you get there and when you are leaving. Please be safe. Please, please please let her be safe.

Violence and sexual harassment against women and girls has reached epidemic proportions. You can boast about it today and still get elected to the most powerful office in the world.

Much of this takes place in the private domain. When it happens in the public domain, females are typically held responsible: "Why was she walking there at after dark?" "Girls can't ride the bus alone. She should have known better." "You can't wear a dress like that and not expect trouble."

The geography of fear also varies for different kinds of women according to race, religion, disability, gender identification and class. (Peake, 2017)

Our cities aren't designed for our daughters or their mothers. Cities have been designed with the needs of men in mind, for a time when women did mostly unpaid work and community work.

Studies show that women have different transport needs. We have different travel patterns. We have different public space needs. Overall, our incomes remain lower so we have different housing needs, child care needs, and elder care needs.

These realities are not reflected in our city building efforts. Why not?

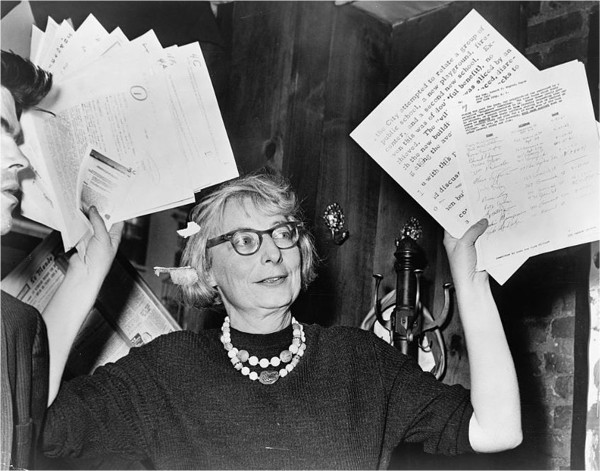

The most influential urbanist in modern times was and remains a woman.

Jane Jacobs in Greenwich Village

The most progressive urban advocates today are women. Janette Sadik-Khan, Sharon Zuker, Marjora Carter and Toni Griffin are calling for changes to how we plan and design cities with the goal of making them more inclusive, healthier, safer and sustainable.

Closer to home, city planners Jennifer Keesmat and Mary Lou Tanner, along with Jay Pitter and Hamilton architect Emma Cubitt, are championing similar themes.

This should surprise no one. These women have a heightened sensitivity of the urban precisely because they are women.

Jane Jacob's groundbreaking theory of cities was born of her femaleness and her motherhood. She was dismissed by the mighty Robert Moses on both grounds. Jacobs used her network as a mother to organize, and her knowledge of the city as a woman to put forward a better idea than the one being driven by Moses. She was the beginning of his end.

Last weekend I got to view the city through Jane Jacob's eyes a second time with the screening of the documentary "Citizen Jane: Battle for the City". This time, I saw so much more.

This time, I became aware that my view was similar to Jane's, which may explain what escaped my gaze the first time I watched the film.

Robert Moses pursued a policy of ethnic cleansing in his hyper-masculine approach to city building. He dismissed women, but he targeted the poor. He went after Americans of colour and de-legitimized their rights to the city. But with the exception of one short interview, the documentary didn't offer these neighbours a voice, and neither, it seems, did Jane.

When we saw women who didn't look like Jane, they were not with Jane. Instead, they were hanging out on city street corners or apartment windows. Their voices were given no platform and therefore their experience in the city, no voice.

I hope my view of the city will change yet again. I hope to listen to the voices of mothers and women who don't look like me, sound like me or live near me.

I hope to get a better view of my city.

By sparrowswain (anonymous) | Posted October 24, 2017 at 08:04:53

Thanks for this insightful and thoughtful piece.

By SusanHill (registered) | Posted October 25, 2017 at 13:32:34

Thank you for a very insightful piece. You hit the nail on the head with your observation: "It is a city built for speed and cars, not people and especially not for children. And it is all these things not by accident, but by design." Hamilton desperately needs to re-think its philosophy regarding our streets as the mindset still seems to favor maximum speed and traffic flow. All you have to do is take a walk down Main St W or Queen St to know that vehicle speed is high on the list of our city's priorities. These streets are not welcoming or safe for people of any age, and yet little is done to transform them into more hospitable spaces.

This mindset must change if Hamilton is to ever reach its full potential. It's time our leaders and planners muster the political will to take the bold steps necessary to move Hamilton out of its Moses-inspired design of the 60's and into to a Jacobs-inspired liveable, walkable, bike-able, and prosperous city of the future.

You must be logged in to comment.

There are no upcoming events right now.

Why not post one?